Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2015 May 7

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < May 6 | << Apr | May | Jun >> | May 8 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

May 7

[edit]Speed of light, dark energy, dark matter

[edit]Could it be that dark matter and dark energy necessary exists, only because the speed of light in a vacuum and/or other values are assumed to be constants? I recall an unexplained discrepancy, when the LHC experimentally determined the mass of a proton, and found it to be in disagreement with the established value. Could the speed of light actually be dependent on distance, where a small change only becomes noticeable over galactic distance? Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:15, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Sure, why not? --Jayron32 01:43, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Surely there must be a logical reason why I've not heard of any such idea investigated by a prominent scientist. I would consider this a case in point of Occam's Razor - conceding an error of assumption is a far simpler path than inventing mysterious matter and energy, and deriving all the physics involved. Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:49, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Why do you think that the proton mass or dark matter and energy have anything to do with a variable speed of light? No one has investigated this idea because it isn't an idea, just a juxtaposition of headlines you saw in Discover magazine. -- BenRG (talk) 07:50, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- That was something close to what I was thinking, but then again, who knows. PP, if you have a mechanism in mind according to which a variable speed of light would explain the observations that induce cosmologists to postulate dark matter and dark energy, please do enlighten us.

- Actually, since the two things (dark matter and dark energy) have basically nothing to do with one another except the word "dark" and the fact that we don't know their origin or composition in detail, maybe just pick one of the two and start with that. --Trovatore (talk) 08:08, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I don't have a mechanism in mind, but there is clearly a link, since the speed of light features in virtually all formulas relevant to cosmology. The gravitational constant is it self a function of the speed of light. All that remains is to find the dependency of the speed of light on space-time. I raised the point about the proton mass to exemplify how another constant is not so constant after all, it's not only LHC that reported a discrepancy, a few observatories also gave similar reports when studying the more distant gas clouds. Plasmic Physics (talk) 08:35, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- The speed of light is important because of basic relativistic mechanics. Since all motion is relative to the speed of light, it will show up in any calculation where anything moves. Which is pretty much every physics calculation--Jayron32 13:00, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Not just relativity, but most electromagnetic phenomena also depend on the speed of light. The absorption and emission spectra of atoms are considered one place where changing physics might reveal itself over time. People have looked for that, and perhaps the best that can be said at the present is, if there is any variation in electromagnetic coupling over space/time then the variation isn't very large (no more than parts per million). Dragons flight (talk) 16:14, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Well, exactly my point. Is something moving, or have the potential to move in electromagnetism? If yes, speed of light will enter into the calculations. Since physics = the science of motion, the speed of light is a fundamental concept that will show up in almost every single calculation somewhere. --Jayron32 16:16, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Not just relativity, but most electromagnetic phenomena also depend on the speed of light. The absorption and emission spectra of atoms are considered one place where changing physics might reveal itself over time. People have looked for that, and perhaps the best that can be said at the present is, if there is any variation in electromagnetic coupling over space/time then the variation isn't very large (no more than parts per million). Dragons flight (talk) 16:14, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Blood is in virtually every part of the human body, so cancer and asthma and this other disorder that's in the news must be related to blood, and we could cure them by reducing the amount of blood. Physicians should investigate that, but maybe they're reluctant to admit that their careers have been a lie.

- The proton discrepancy that you're talking about is presumably the discrepancy in the charge radius. Maybe you read this article which says "proton mass" in the headline even though it talks about size in the body, suggesting that Discover's editors don't know the difference between mass and size, which is pretty bad even by the usual awful standards of these publications. Different attempts to measure the charge radius by different methods give inconsistent results. Since they don't measure the radius directly but rather calculate it from indirect evidence, the natural explanation is that there's an error in the calculations. It could be a sign of new physics (rather than just a simple error), but even if it is, it's new physics that invalidates their calculation of the radius, not new physics that means the radius is not constant. -- BenRG (talk) 17:29, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- The speed of light is important because of basic relativistic mechanics. Since all motion is relative to the speed of light, it will show up in any calculation where anything moves. Which is pretty much every physics calculation--Jayron32 13:00, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I don't have a mechanism in mind, but there is clearly a link, since the speed of light features in virtually all formulas relevant to cosmology. The gravitational constant is it self a function of the speed of light. All that remains is to find the dependency of the speed of light on space-time. I raised the point about the proton mass to exemplify how another constant is not so constant after all, it's not only LHC that reported a discrepancy, a few observatories also gave similar reports when studying the more distant gas clouds. Plasmic Physics (talk) 08:35, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- See variable speed of light. --Modocc (talk) 14:29, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Thank you. I didn't know we had an article on that, although I should have guessed, since WHAAOE. Plasmic Physics (talk) 21:33, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

beating dogs (and other animals) to improve the flavor of the meat

[edit]In online forums and blogs (and occasionally in mainstream press articles), I sometimes hear the claim that certain peoples in various Asian countries try to inflict as much pain as possible on dogs and other animals before they slaughter them. The reason given is that this somehow makes their meat taste better. Western travelers to remote areas claim to have witnessed this pratice first-hand.

But to me, it sounds like a strange claim, as I've heard that slaughterhouses in America try to keep animals calm, not for humane reasons, but because if the animal is frightened, it somehow degrades the quality of the meat.

I've heard further claims that those two slaughter methods are not necessarily contradictory and that the beating/torture technique is intended to stimulate all the meat-ruining adrenaline so that it can then leave the system, after the animal has been sufficiently beaten,leaving the meat pure.

I find these claims are as poorly sourced and sketchy as they are shocking. Is there anywhere I can read a dispassionate description of this practice as well as whether there is any science behind it (i.e., beating or not beating an animal and its effect on the taste/texture of meat)? When I google it, all I can find are very emotional and sensationalist accounts by animal welfare groups, who are very rightfully upset, as it's a very cruel practice. But I don't need to be told it's cruel (that seems obvious, at least to those of us in the West who are socialized to care about dogs)--I am just wondering if there's any actual utility/purpose to the practice.

In short, do people really do this? Is there any evidence that it works?--Captain Breakfast (talk) 09:35, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Hi There is a good body of science behind keeping animals as calm and unstressed as possible before slaughter. Excessive stress before slaughter can lead to a condition called PSE meat. In addition, having stressed animals before slaughter can lead to them becoming more aggressive and bruising each other. Both can be extremely costly. As for beating animals before slaughter, I do not know of this. But, it could certainly change the texture of the meat - but bruised meat is generally thought to be less palalatable (at least in Western culture). I don't think beating would be succesful at ridding the body of adrenaline as the body can produce adrenaline de novo under conditions of stress, e.g. by beating. So, I doubt the body would ever be rid of adrenaline.DrChrissy (talk) 11:46, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I would expect that beating animals would result in blood in the muscle tissue. Most Westerners don't like the taste of blood (the iron specifically makes it taste bad), but I suppose others might, particularly if they were deficient in iron (bone marrow is a good source of blood, too). Of course, there are easier ways to mix blood with meat, and blood rapidly goes bad, so doing the mixing immediately after the blood is removed from the animal and right before cooking would make the most sense. Also note that it isn't necessary to slaughter an animal to get blood from it. I believe there's a tribe in Africa that keeps cattle, and draws some blood to mix with milk to make a drink. StuRat (talk) 12:01, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- That would be the Maasai people. DMacks (talk) 14:38, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Yep, that's them. Thanks. StuRat (talk) 21:38, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- @ StuRat "Bone marrow is a good source of blood too", Really? have you ever seen or eaten bone marrow? not much blood at all, mostly gelatine and fat cells. Richard Avery (talk) 07:30, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- Perhaps I should have said iron. That's where red blood cells are formed, and it has a definite metallic taste as a result. StuRat (talk) 01:01, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- It certainly is a belief that stress hormones tenderise the meat (not the bruising of the meat) see:here. I was also told once by a vet who worked in the meat industry in the UK that people who steal deer to sell as venison like to chase them around before they shoot them as they believe it will make the meat is more tender. I don't expect that much scientific research has been done on this as it would be difficult to construct an ethical experiment. Richerman (talk) 13:34, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- And I've heard just the reverse, in the case of turtle soup, that the turtles must be killed instantly to avoid stressing them out. StuRat (talk) 18:34, 11 May 2015 (UTC)

Dairy cattle and osteoporosis

[edit]Human women who nurse are subject to osteoporosis. As I understand it, calcium is removed from the bones to add to the milk. So then, does the same happen with cattle ? It seems that we force them to produce far more milk in their lives than is natural. If not, why not ? What protection do cattle have against calcium loss, and can this protection be extended to women ? StuRat (talk) 12:08, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I think you've made a false link. Women lactate; women are more subject to osteoporosis; therefore lactation causes osteoporosis. This, for example, says that osteoporosis is more common in older women, past the menopause: hardly a time of significant lactation. It cites hormonal changes as the major cause, and does not mention lactation at all.--Phil Holmes (talk) 16:14, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- Their bones are depleted of calcium both during lactation and after menopause. The cumulative effect of both can be brittle bones. And note that your assumption that the effect must occur concurrently or immediately after the cause is a logic error. Take shingles, which occurs years after having chickenpox, or cervical cancer, which can occur long after contracting HPV, or skin cancer, which can occur decades after getting severe sunburns. StuRat (talk) 16:21, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- I've provided a link from a Governmental health organisation that suggests no link with lactation. Could you cite some actual evidence for your unbased assertion?--Phil Holmes (talk) 19:46, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- Googling "calcium during lactation", I found quite a few entries, including this, which says calcium tends to be depleted both during pregnancy and lactation. Challenging facts is fine. Firing shots at fellow editors is not. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 20:37, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- That link says that extra calcium is needed during lactation. It also says that this comes from milk, and the information is provided by "The Dairy Council", so no surprises there. However, the link provides no link between lactation and osteoporosis. Stu is continuing to make stuff up rather than provide properly referenced information. The shot I fire is that this supposed to be a reference desk, with information referenced rather than assertions that something is true because the editor thinks it might be.--Phil Holmes (talk) 09:09, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- I'm not trying to insult you: merely to point out that you are quoting as fact something that appears simply untrue. Your initial statement is "Human women who nurse are subject to osteoporosis." I believe this to be completely false, based on the link I quoted and even the links you quote: the final one says that calcium deficiency from lactation is reversible and at most, a very minor possible cause of osteoporosis. Imagine that you were a mother about to give birth and followed a link to this ref desk and read that "Human women who nurse are subject to osteoporosis." If there was not a follow up statement pointing out that this has no basis in fact, you could end up changing the way mothers nurse their children, with likely adverse affect on their childrens' health - see, for example, this study on development in children and the effect of breast feeding. I would argue I belong here as a qualified scientist who checks references before inventing non-facts. Thanks for the insult, though.--Phil Holmes (talk) 15:44, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- "Completely false" and "a very minor possible cause of osteoporosis" are incompatible. If it's a cause, even a minor one, that's not "completely false". And that's all quite irrelevant to my Q, which was how cattle deal with the continuous loss of calcium from constant lactation. All of my sources showed that calcium loss does occur due to lactation in women. Whether this eventually leads to osteoporosis in women is a minor quibble, and we've wasted way too much time on it. I think me pointing out your logic error made you angry, and you decided to "get even". StuRat (talk) 23:39, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- Just looking through the abstracts of the studies you linked to, most of them say something along the lines of " Pregnancy-and lactation-associated osteoporosis is an uncommon condition that may be a consequence of preexisting low bone density, loss of bone mineral content during pregnancy, and increased bone turnover. So it's obviously not a general problem in lactating women and you wouldn't expect it would normally be a problem in cattle, providing they get enough calcium in their diet. Richerman (talk) 12:41, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- In women: The calcium loss in the bones often occurs, but only rarely rises to the level of causing osteoporosis during lactation. However, this calcium loss can set them up for osteoporosis later in life, post menopause, when additional calcium loss can occur, unless they replace the calcium in the bones after lactation: [3].

- In cattle: My question here is based on dairy cattle producing far more milk than they would in nature, with little opportunity to replenish the calcium, post-lactation. StuRat (talk) 12:59, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- An example showing that breastfeeding can actually reduce the indicence of osteoporosis is here: "Another important element used in producing milk is calcium. Because women lose calcium while lactating, some health professionals have mistakenly assumed an increased risk of osteoporosis for women who breastfeed. However, current studies show that after weaning their children, breastfeeding mothers' bone density returns to prepregnancy or even higher levels (Sowers 1995). In the longterm, lactation may actually result in stronger bones and reduced risk of osteoporosis. In fact, recent studies have confirmed that women who did not breastfeed have a higher risk of hip fractures after menopause (Cummings 1993)."--Phil Holmes (talk) 16:06, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- If you read for Preventing Milk Fever in Dairy Cattle by Horst et al it says in the discussion:"Noticeably, milk fever is very rare in first lactation cows; incidence increases dramatically in third and greater lactations. Several factors contribute to the aging effect. Advancing age results in increased milk production, resulting in a higher demand for Ca. Aging also results in a decline in the ability to mobilize Ca from bone stores and a decline in the active transport of Ca in the intestine, as well as impaired production of 1,25(OH)2D3". It also discusses strategies for dealing with the problem. Richerman (talk) 13:21, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

Ladybirds

[edit]What is the difference between primarily red with black dot-type ladybirds, and primarily black with red dot-type ladybirds? It might be an old wives' tale, but when I was a kid, I was taught that the black ones sting/bite. I've never been bitten nor stung by any kind, and we have loads of them in our gardens. KägeTorä - (影虎) (もしもし!) 13:04, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Here's a link to ladybird ("ladybug" in the US). StuRat (talk) 13:15, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- They are just different members of the Coccinellidae, or even just different colorations of the same species (polymorphism_(biology)). To my knowledge, none of them are all that different in terms of behavior, with the exception of the asian ladybug, whose population has skyrocketed in the USA in recent years (also note the variety of colors/patterns in that species). They can be a bit of a pest, and swarm in to homes in the cool season. I don't think any beetle can sting, though ladybirds will bite on occasion (rather minor, no lasting mark or itching). My impression is that the asian ladybird beetles might be a little more likely to bite, but that may just be an artifact of the fact that they occur in bigger swarms, which would increase your chances of being bitten. SemanticMantis (talk) 13:19, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Thanks, both of you. I didn't take it seriously, to be honest, believing it to be an old wives' tale. And Stu, I prefer the term 'ladybird', because 'ladybug' is the word I had to teach in Japan (as schools prefer American English), and to me it sounds like a venereal disease. 'Ladybird' sounds so much better, as a harmless little creature. KägeTorä - (影虎) (もしもし!) 13:35, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- (EC) SM, that link just reminded me of something we did as children, as a good luck charm. We get them to crawl onto our little finger, and then blow them away, making a wish at the same time. Is this practice common anywhere else? KägeTorä - (影虎) (もしもし!) 13:43, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I see from the link that the asian beetle is indeed in the UK now, so you probably see mostly that type, though there will still be natives mixed in at lower concentrations. If you see more these days than when you were young, the explanation is probably the invasive species. Distinguishing the species is rather difficult for the non-expert, because color is useless, you have to look at the pronotum to make sure. Keep your eye out for the larvae, they look like fierce little dragons, and many people wouldn't recognize them as beetles [4]. As for names, I prefer "ladybeetle" - as it clearly indicates the beetle status ;) SemanticMantis (talk) 13:41, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Thanks, both of you. I didn't take it seriously, to be honest, believing it to be an old wives' tale. And Stu, I prefer the term 'ladybird', because 'ladybug' is the word I had to teach in Japan (as schools prefer American English), and to me it sounds like a venereal disease. 'Ladybird' sounds so much better, as a harmless little creature. KägeTorä - (影虎) (もしもし!) 13:35, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- We used to recite "Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, your house is on fire and your children are flown" while the ladybird was on the little finger, before blowing it and making a wish. There is an interactive UK ladybird spotter, as well as spotter charts and more information on the UK Ladybird Survey website. DuncanHill (talk) 14:05, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I knew it wasn't a false memory. Thanks, Duncan! KägeTorä - (影虎) (もしもし!) 18:54, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Huh. A variant of that line also occurs in Tom Waits' Jockey Full of Bourbon, but I never knew the referent. Listen here if you're interested [5]. SemanticMantis (talk) 21:05, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Of course, we have an article: Ladybird Ladybird. In London, her "children are gone!" Alansplodge (talk) 21:36, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I learnt that nursery rhyme in school in the US back during the Nixon Administration. We realized that ladybird was a mistake for the proper term ladybug from the illustrations. The only people who need feaar being bit by ladybugs are aphids. As for Ladybird, that is a title for the wives of American presidents. μηδείς (talk) 22:22, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- A personal anecdote, I know, but I was bitten by several ladybirds in the summer of 1976, when we had a veritable plague of them in the UK. It wasn't very painful, and it's true that they don't sting, but they are not entirely innocuous. Tevildo (talk) 18:10, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- You will find that in the article - with citations! Well - not that you personally were bitten, but people in general were see: Coccinellidae#Infestations and impacts And, of course, it's ladybug that's a mistake - they're not bugs at all. You wouldn't believe how much trouble the difference in names causes for that article. Richerman (talk) 19:08, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- I'll assume Cardinal Fang had the two of you in the comfy chair while this was going on? μηδείς (talk) 20:57, 10 May 2015 (UTC)

- You will find that in the article - with citations! Well - not that you personally were bitten, but people in general were see: Coccinellidae#Infestations and impacts And, of course, it's ladybug that's a mistake - they're not bugs at all. You wouldn't believe how much trouble the difference in names causes for that article. Richerman (talk) 19:08, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- A personal anecdote, I know, but I was bitten by several ladybirds in the summer of 1976, when we had a veritable plague of them in the UK. It wasn't very painful, and it's true that they don't sting, but they are not entirely innocuous. Tevildo (talk) 18:10, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- I learnt that nursery rhyme in school in the US back during the Nixon Administration. We realized that ladybird was a mistake for the proper term ladybug from the illustrations. The only people who need feaar being bit by ladybugs are aphids. As for Ladybird, that is a title for the wives of American presidents. μηδείς (talk) 22:22, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Of course, we have an article: Ladybird Ladybird. In London, her "children are gone!" Alansplodge (talk) 21:36, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Huh. A variant of that line also occurs in Tom Waits' Jockey Full of Bourbon, but I never knew the referent. Listen here if you're interested [5]. SemanticMantis (talk) 21:05, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I knew it wasn't a false memory. Thanks, Duncan! KägeTorä - (影虎) (もしもし!) 18:54, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- We used to recite "Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, your house is on fire and your children are flown" while the ladybird was on the little finger, before blowing it and making a wish. There is an interactive UK ladybird spotter, as well as spotter charts and more information on the UK Ladybird Survey website. DuncanHill (talk) 14:05, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- FWIW, I was always taught as a kid that the black-with-red-spots type were poisonous while the red-with-black-spots ones were harmless. There were some that were yellow with block spots too. I assumed that they were the red type that hadn't 'ripened' yet. --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 22:05, 10 May 2015 (UTC)

Is there a connected multi-tooth veneer ? If so, does it still require an adhesive or grinding down the existing teeth ? Veneer (dentistry) doesn't list any. StuRat (talk) 14:28, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Wouldn't a "connected multi-tooth veneer" be a "grill"? --Jayron32 15:50, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Yes, except that as it says "Grills are made of metal". I'd looking for the same thing, but with white ceramic or other white material (titanium dioxide is both white and partially metal, but it reacts with calcium, so not a good choice here). StuRat (talk)

Oxygen content of the atmosphere

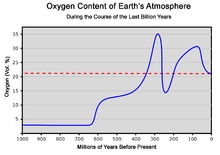

[edit]Atmosphere of Earth gives the Earth's oxygen content as 20.946%. Does it stay that constant? Bubba73 You talkin' to me? 17:48, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- No, neither as a percent composition nor as a total amount. For example, we just reached a global average of 400 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere. If the relative proportion of one compound is on the rise, this impacts the relative proportion of other compounds within the atmosphere. Additionally, there are sources adding oxygen to the atmosphere, such as plant photosynthesis, and actions that remove it, such as combustion and aerobic respiration. These will all have their own impacts on the precise percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere. That said, all of these factors may be either well balanced or very small in impact to the point that, over the significant figures in your percentage, the number may not be changing. That is not the same thing as being a constant. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 17:57, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- CO2 levels do not significantly affect oxygen levels. Look at the number you just quoted. CO2 has risen to 400 ppm. That's parts per million. Oxygen is 20.946 %. That's parts per hundred. 400 ppm is 0.0400%, which means it would just start to budge the oxygen amounts, but not by much. While your general point may be sound (that is, the relative amounts of other gases DO affect O2), significantly CO2 is just not one of those gases. The Earth's atmosphere today is basically only 3 gases which have any individual statistical significance: nitrogen, oxygen, and argon (in that order). Everything not one of those gases only accounts for about 500 ppm, or 1 20th of one percent. The amount of oxygen does change dramatically as noted below, but only on very long time scales. An interesting article to read would be Great Oxygenation Event, which is believed to correspond roughly with the origin of life. --Jayron32 19:08, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Don't forget water vapor... Short Brigade Harvester Boris (talk) 02:32, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- That's why I said the impact would likely be below the significant figures of the percentage given. Not sure what you are responding to since I had already said that. That said, 1/20th of 1 percent could actually put that in the significant figures of the percentage given (20.946% vs. 0.05%, or in the case of 400 ppm, 0.04%), so actually, CO2 level changes could be significant enough for the percentage of O2 given. After all, a change of 50 ppm (say for 350 ppm to 400 ppm) could be significant enough for a change from 20.941% to 20.946% O2. That would only work if the only other gas impacted was oxygen, of course, which I doubt. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 23:02, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- The small rate of decline of atmospheric oxygen is used to help us figure out the budget of CO2 produced by fossil fuel combustion. The decrease in O2 is consistent with the amount of oxygen needed to burn fossil fuels, reduced by a (somewhat uncertain) sink. See for example Keeling et al. (1996), Nature, 218-221. Short Brigade Harvester Boris (talk) 02:30, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- CO2 levels do not significantly affect oxygen levels. Look at the number you just quoted. CO2 has risen to 400 ppm. That's parts per million. Oxygen is 20.946 %. That's parts per hundred. 400 ppm is 0.0400%, which means it would just start to budge the oxygen amounts, but not by much. While your general point may be sound (that is, the relative amounts of other gases DO affect O2), significantly CO2 is just not one of those gases. The Earth's atmosphere today is basically only 3 gases which have any individual statistical significance: nitrogen, oxygen, and argon (in that order). Everything not one of those gases only accounts for about 500 ppm, or 1 20th of one percent. The amount of oxygen does change dramatically as noted below, but only on very long time scales. An interesting article to read would be Great Oxygenation Event, which is believed to correspond roughly with the origin of life. --Jayron32 19:08, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Additionally, the portion of oxygen in the atmosphere has changed over the course of the Earth's existence, including over the last several hundred million years. See Atmosphere of Earth#Third atmosphere and the figure at right. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 18:00, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- And for more short-term variations see this paper. If I am reading Fig.1 correctly, the seasonal variation is few 10s of ppm, with year-to-year variation being few ppms. So the last digit in 20.946% may vary by 2-3 within a year, and over a decade. Abecedare (talk) 20:28, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

Effect on large dinosaurs ?

[edit]One theory I've heard is that large dinosaurs required a high oxygen content in the air. So, did the age of large dinos correspond with the high points on the chart ? StuRat (talk) 20:18, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Look at Dinosaur, which puts them appearing at 231 mya, dominant until 66 mya. Lungs are tricky though. It is true that higher concentrations of O2 allowed for bigger insects in e.g. the Jurassic. Here's a paper on the topic of the Paleozoic O2 spike and consequences for physiology and evolution [6] SemanticMantis (talk) 20:53, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Based on the figure I posted above, oxygen levels do look to have been higher during the age of dinosaurs than today, as much as 30% or so vs. the 21% of today. Whether that enabled larger dinosaurs is another matter altogether. We have larger air breathing animals today, such as the blue whale. How much oxygen a whale needs vs. a dinosaur and indeed how much oxygen a dinosaur needed is well beyond my skills. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 23:06, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Whales swim in the water, and I believe that's far more efficient than running is, requiring less oxygen. StuRat (talk) 22:22, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- I had thought of that, but consider that whales need to do that without constant access to new air. They get a gulp of air, and then that's all they have for awhile while swimming. --OuroborosCobra (talk) 22:33, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- Whales swim in the water, and I believe that's far more efficient than running is, requiring less oxygen. StuRat (talk) 22:22, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- This thesis is the subject of the book Out of Thin Air. μηδείς (talk) 22:18, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

Thanks for the responses. I knew that the oxygen level must change some and I know it changes over long periods. But it seems to be remarkably close to being constant, i.e. very well balanced. Bubba73 You talkin' to me? 23:05, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

Predictions of temperature fluctuations

[edit]Why, in some places, the weather is so stable year-round, whereas in other places, the temperature can drop and rise extremely, leaving little room for comfortable and cool temperatures? What are all the variables that may influence the temperature at a specific location? Distance from the equator, amount of sunlight, number of clouds, water bodies, mountains, global climate change, etc.? 164.107.182.34 (talk) 18:17, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- The largest factors are latitude, with locations farther from the equator being more variable (both seasonally and daily), and distance from large bodies of water (especially oceans) due to the moderating effects of water's large thermal inertia. On a day-to-day basis, the presence or absence of cloud cover can make a big difference. Winter months tend to have more variability than summer months, and this is especially true is areas with sporadic snow cover. Dragons flight (talk) 18:35, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Agree, but note that bodies of water lose their moderating effect when completely covered with ice. At that point, they behave like land, as far as the weather is concerned. Thus polar regions can hit extremely low temperatures, even small islands in the middle of the Arctic ocean. StuRat (talk) 20:11, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- The OP would be well served to start with an article like Climate and then follow links from there. The broad, average weather trends for a specific location is called "climate", so looking in to what causes the climate of an area will lead to understanding the issue. A common scheme is the Köppen climate classification system, and our article (and articles on the specific Köppen climate types) go into some considerable detail which should answer the OP's question. --Jayron32 18:57, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

The force that pushes me outward

[edit]The centripetal force is the force orthogonal to the circular pathway, pointing at the center. Driving on a highway or riding on a roller coaster, you may feel a force that pushes you in the opposite direction of the vehicle movement. What is that force called? Or perhaps, you are feeling the force that pushes you in the linear direction, tangent to the "circle", but the circular pathway forces you to go in the circular motion instead of flying out of the circular motion? Is there a reason why the circular highway roads often have a set diameter, given the average speed limit of the road? 164.107.182.34 (talk) 20:16, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- The apparent (sometimes labelled "fictitious") outwards force is called centrifugal force. For any given radius, there is a maximum speed at which it is possible to follow the circular road without skidding, but this speed depends on the road surface and the tyres. A tangential force is felt when the speed is changing. Here in the UK, the radius of the circle varies, but when expected speeds are higher the radius is greater so that skidding is less likely. The frictional force at the tyres needed to keep a vehicle going round in a circle is proportional to the square of the speed, and inversely proportional to the radius. See the article on circular motion for details. Dbfirs 20:32, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Centrifugal force is labeled a fictitious force because it is one. Another synonym for "fictitious force" is "inertial force." I think the OP's question is probably better understood in terms of momentum and inertia, and Newton's first law. The units are different from force. When you feel "pushed to the left" as your car turns to the right, there is no actual force pushing you to the left. That's why centrifugal force is a fictitious force. Rather, the car is supplying a centripetal force to you and you only feel pushed to the left because of your frame of reference in the car, and your inertia. I'm just trying to explain the same thing you are, but with slightly different words. I'm not sure, but I don't think the fictitious force of centrifugal force is even taught that often in high school and non-major physics at the undergraduate level any more. Most courses that I'm familiar with stick to centripetal force and inertia/momentum. SemanticMantis (talk) 20:46, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Yes you are correct that it isn't taught (for good reasons). I mentioned the word "centrifugal" only because the OP asked for the word, so I linked to our article. In my teaching, I never mentioned either "centrifugal" or "centripetal" except to warn about mis-use. Were I inclined to totalitarianism, I would ban the words because of widespread misunderstanding, but I do occasionally use the concept of centrifugal force in my own thinking as a shortcut to an answer within a limited rotating frame. Dbfirs 21:36, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Centrifugal force is labeled a fictitious force because it is one. Another synonym for "fictitious force" is "inertial force." I think the OP's question is probably better understood in terms of momentum and inertia, and Newton's first law. The units are different from force. When you feel "pushed to the left" as your car turns to the right, there is no actual force pushing you to the left. That's why centrifugal force is a fictitious force. Rather, the car is supplying a centripetal force to you and you only feel pushed to the left because of your frame of reference in the car, and your inertia. I'm just trying to explain the same thing you are, but with slightly different words. I'm not sure, but I don't think the fictitious force of centrifugal force is even taught that often in high school and non-major physics at the undergraduate level any more. Most courses that I'm familiar with stick to centripetal force and inertia/momentum. SemanticMantis (talk) 20:46, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

There is nothing fictitous about the force. If you hold a rope in each hand and a giant whirls you around his head via the end of one rope, and a large rock is attached to the outboard end of the other Giant----You----Rock , the force you feel in your left hand, say inboard, is no more or less fictitious than the force in your right hand, yet one is towards the centre (centripetal), and one is towards the outside, centrifugal. Calling it fictitious doesn't make it go away. Now, I'd entirely agree most times it is easier to write the equations in an inertial reference frame, but that is not the point.Greglocock (talk) 23:27, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I just call it the tension in the rope, and, as you say, that is indeed real. Calling it "centrifugal force" tends to lead to misunderstandings by those who don't fully appreciate the difference between an inertial frame and a rotating frame of reference. Dbfirs 07:06, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- Actually, it's easier to write the Newtonian force equation (F = m·a) in the non-inertial reference frame - specifically the one whose rotation exactly matches the object that's spinning. That's the frame where the force looks like a constant and you can solve for the equation of motion very simply! If you write the equations in an inertial reference frame, the force (its direction and magnitude) vary with time.

- The tricky parts really come in to play because you can't write all of the forces in the same reference frame. If you were spinning a bucket, and you considered the rotating reference frame inside the bucket, you'd have to consider that the force of gravity varies with time (i.e. because the bucket's orientation is changing as it spins).

- Physicists who have to deal with this problem simply avoid it. After spending a few years of Newtonian mechanics, physicists learn to write equations of motion in terms of energy instead of in terms of force. This is the translation to an equivalent formulation of dynamics: Lagrangian mechanics, Hamiltonian mechanics, or Jacobian mechanics (and so on). In these treatments, we don't care what's rotating or what force it feels: instead, we simply consider how systems will evolve, and what trajectories objects will take, when subject to potential energy systems and external constraints. The accelerations that these objects feel are produced as outputs of the calculations. This makes simple work out of the analysis of non-rigid bodies, rotating (or otherwise transformed) reference frames, and so on. It is how we model vehicle dynamics, robot movement, and complex systems. A classical application: how much torque must be supplied by the motor at robot's wrist, when the robot arm's shoulder-joint is rotating? ... And if the robot arm has six shoulder-joints, each one also moving? If you try to solve that using Newtonian mechanics and a rotating reference frame, you'll give up in a hurry and seek out one of these other analytical methods! Instead, we use mathematical representations of the kinematics that are more suitable for fast calculation, and that account for real effects ("fictitious" or otherwise).

- Nimur (talk) 16:13, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

Would a roller coaster be exciting in space?

[edit]What makes a roller coaster exciting? Is it the gravitational force that pulls the coaster straight down, creating the allusion of a freefall? Would a roller coaster be just as exciting in a gravity-free environment, like in space? 164.107.182.34 (talk) 20:47, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- It is difficult to predict, given that different experiences are involved. I think that the built-up of dread before a massive descent would no longer occur, because there is no descent. All there are in place of descents are rapid changes in curvature. However, the ride would be very disorientating on account of there being no up or down. That in itself could lend a factor of excitement. There's no way to tell whether the tradeoffs are of equal value or not, without a trial and error. Plasmic Physics (talk) 21:20, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Note that a roller coaster, by definition, requires gravity. That is, it's lifted using power, then it's dropped and gravity does the rest. You could power the entire length of the ride, or rely on inertia to finish the trip, but that would result in a gradually slowing ride. Perhaps if you put enough (powered) acceleration at the start, that might make up for the lack of a "drop" in the middle.

- If your space station already has a (human-sized) centrifuge, for health reasons, perhaps you could make that into a virtual roller-coaster, with the aid of some VR goggles, to match the view with the changing g-forces. StuRat (talk) 21:28, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Going to space to ride a rollercoaster is like going to Paris to check out their McDonald's restaurants. I am not sure that a roller coaster requires gravity by definition, as what it requires is acceleration, and the changes in velocity caused by the deflection of a track (or a track substitute). Theoretically that's easy to design.

Females & make-up

[edit]Everything has an evolutionary meaning, make-up included. "Darwin states that any deliberate mate selection is of women by men, not the other way around. Therefore, it is female features that are important in mating success, such as beauty, red lips, shapely breasts, as well as artificial means such as jewellery and make up."... The question is, are females aware that their make-up is a tool for attracting males? --Mr.Pseudo Don't talk to me 22:00, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Yes. StuRat (talk) 22:04, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- You could try asking some. Top tip: adult females of the human species are referred to as 'women'. AlexTiefling (talk) 22:07, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- No concern for the poor adult human males? μηδείς (talk) 22:14, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Oh, good point. Yeah, it's not cool to talk about men like they're specimens in a nature documentary either. AlexTiefling (talk) 22:54, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Enough people behave as animals in this regard, yielding to instinct with little concern for the impact upon dignity or self-worth. Plasmic Physics (talk) 23:01, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Oh, good point. Yeah, it's not cool to talk about men like they're specimens in a nature documentary either. AlexTiefling (talk) 22:54, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- No concern for the poor adult human males? μηδείς (talk) 22:14, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- Sexual selection applies both ways, it explains the showy colors of male songbirds such as the Fairy Wrens and the Cardinal and human penis size. The quoted source is not the best, I'd just read sexual selection. As for humans, being sapient, the answer, as noted, is yes. μηδείς (talk) 22:14, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- I agree that the cited source is no good. The quote is simply not true. I call [citation needed] on the claim that Darwin said any such thing. SemanticMantis (talk) 22:45, 7 May 2015 (UTC)

- If one really wants to understand human behavior from an objective point of view (that is, viewing humans as animals), the landmark work in this vein is Desmond Morris's The Naked Ape; besides the original book there have been several adaptations for film and for television. Morris is the sine qua non of this field of study. --Jayron32 02:11, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- "[...] serialized in the Daily Mirror [...] explanations failed to convince many academics [...] starring Johnny Crawford and Victoria Principal [...]" Why would you recommend this? -- BenRG (talk) 05:01, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- Desmond Morris's standing among academics has little to do with whether his theories are correct or not. In talking about him with my anthropology profs, it seems that a lot of his work is dismissed out of hand because of his apparent focus on treating people as animals (vis a vis his background in zoology). As a "celebrity" he also suffered from the kind of excessive scrutiny guys like Stephen Jay Gould and even Carl Sagan had to deal with. For example, now that he's safely dead, Sagan can get all kinds of posthumous recognition, but alive he was denied membership in the NAS. Personally, I doubt we'll get a proper handle on Morris's methods and conclusions until after he's gone as well. Matt Deres (talk) 13:33, 9 May 2015 (UTC)

- "[...] serialized in the Daily Mirror [...] explanations failed to convince many academics [...] starring Johnny Crawford and Victoria Principal [...]" Why would you recommend this? -- BenRG (talk) 05:01, 8 May 2015 (UTC)

- The Descent of Man is in the public domain and you can read it for free online. That page does seem to misrepresent what he said. The closest I can find in the book is "Man is more powerful in body and mind than woman, and in the savage state he keeps her in a far more abject state of bondage than does the male of any other animal; therefore it is not surprising that he should have gained the power of selection. Women are everywhere conscious of the value of their own beauty; and when they have the means, they take more delight in decorating themselves with all sorts of ornaments than do men." But then he goes on to list examples of savage women having some choice of their mates and says "We thus see that with savages the women are not in quite so abject a state in relation to marriage as has often been supposed." And he seems to think the civilized races are quite different, saying "Civilised men are largely attracted by the mental charms of women, by their wealth, and especially by their social position; for men rarely marry into a much lower rank. [...] With respect to the opposite form of selection, namely, of the more attractive men by the women, although in civilised nations women have free or almost free choice, which is not the case with barbarous races, yet their choice is largely influenced by the social position and wealth of the men [...]." The only mention I noticed of shapely breasts is a statement that Northern American Indians are especially attracted to "breasts hanging down to the belt", as one of many examples of differences in standards of beauty between different races. There are also amusing passages like "The resemblance of Pithecia satanas with his jet black skin, white rolling eyeballs, and hair parted on the top of the head, to a negro in miniature, is almost ludicrous." So maybe you should not take what Darwin says as gospel. -- BenRG (talk) 05:01, 8 May 2015 (UTC)