Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2012 May 6

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < May 5 | << Apr | May | Jun >> | May 7 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

May 6

[edit]Chemical smells

[edit]Do amines smell different, depending on whether they are primary, secondary, or tertiary? How do they compare with imines? Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:00, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

I'm asking because, butan-1-ol, ethoxyethane, butanone, and butanal all smell different from each other. Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:18, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I would imagine that each smells distinct, though it may take some training to tell them apart. --Jayron32 02:28, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Why would it be so much harder? Plasmic Physics (talk) 11:12, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I didn't say it would be any harder than anything else. Just that, exactly like anything else, you'd need some learning in the matter, such as reading the label, smelling it a few times, and getting used to the differences. Pretty much exactly like learning any smell. --Jayron32 12:33, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Why would it be so much harder? Plasmic Physics (talk) 11:12, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Smells depend ultimately on olfactory receptors. Humans have close to 1000 distinct olfactory receptors, each with its own idiosyncratic sensitivity to some aspect of molecular structure. So it is extremely difficult to predict in a principled way which types of smells will be distinguishable from which other types of smells. Looie496 (talk) 17:46, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I think that there might be some regularity - namely, my suspicion is that pitch is a universal characteristic of all sensation, including smell, and that the smell of larger/longer compounds is lower-pitched than that of smaller ones. At least, this is the subjective sensation I have in response to smelling various hexanes and alcohols. But such data as comes easily to hand doesn't really look like it agrees with me, and as for determining the exact functional group ... that seems harder to say. Who has the chance to smell enough of these amines and imines side by side? It's a good question though! Wnt (talk) 06:21, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

Where does the vitamin D in polar regions come from?

[edit]The inuit get their vitamin D from eating fish and seals. The fish and seals get their vitamin D from their diet, and ultimately all vitamin D found in nature is produced from UVB radiation. But in the polar regions, the Sun is so low in the sky that all the UVB radiation is filtered out of the sunlight before it reaches the ground. So, where does the vitamin D come from? Count Iblis (talk) 01:21, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- You need very little UVB to make vitamin D, and luckily, they get very little UVB. StuRat (talk) 01:53, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- The text at Vitamin_D#Production_in_the_skin directly contradicts Count Iblis's assertion that not enough UVB exists in polar regions. I have no idea who is right and who isn't, except to note that the Wikipedia article (and presumably the references) says that it isn't a problem. --Jayron32 01:59, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- We had a question related to this a while back, and I worked out at that time that based on the literature, a sun angle of about 30 degrees above the horizon is required for significant vitamin D production. If that's right, then in the far north there will be part of the year where there is no production, but only part of the year. Looie496 (talk) 03:39, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Our article at the current time seems to support this view. CI's claim is unclear, it seems to suggest year round there is no production whereas Jayron32 may have simply been pointing out our article suggests there is sufficient opportunity to for vitamin D production in spring, summer and autumn. (Our article specifically notes that during the summer some northern parts of Canada have greater levels of UVB then in the equator.) Nil Einne (talk) 05:33, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I believe you find quite a bit of vitamin D naturally in fish, which is incidentally a common source of food for natively northern cultures. Someguy1221 (talk) 04:21, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I think the question here is how it occurs 'naturally'. If CI's claim is true and all vitamin D is produced by UVB (which our article supports) the question still remains how the fish get it in the first place, somehow it must come from UVB. But considering the evidence above from our article that even fairly far north, it's only during winter that's it may be a problem, it's possible fish and other organisms which naturally live in such latitudes are adapted to storing sufficient vitamin D from the rest of the year for use during winter. I had a brief search but didn't find much about vitamin D in fish (except that it's a good dietary source for humans). Nil Einne (talk) 05:33, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- An important consideration is that vitamin D can be stored in fat and in the liver for months, so it isn't necessary for an animal to produce or consume adequate amounts of it every month of the year. The general rule is that the fat-soluble vitamins, namely A, D, E and K, can be stored for fairly long periods of time, so it's less important to have a good supply of them constantly, whereas a more regular source needs to the be available of the water-soluble vitamins like C. Vitamin B12 breaks the rule in that it's water soluble, but it can be stored for a long period (400 day half-life in a human liver) anyway. Red Act (talk) 05:41, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- The fish and seals might migrate. In the case of fish, I wonder how they get enough sunlight, do they come to the surface to "sunbathe" ? StuRat (talk) 06:14, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

Well, looking into this more, I find this, a study which shows that even the full winter sun promotes no vitamin D synthesis in Boston. Further north, in Edmonton, vitamin D can only be synthesized for six months out of the year. But given its slow loss from the human body, that would seem to be enough. But certainly, there are entire freaking countries further north than Edmonton, but maybe even six months of vitamin D synthesis is more than you need.

Looking for actual information on vitamin D synthesis in fish, I am similarly having trouble finding anything. I did find one old paper explaining that aquarium-reared catfish require dietary vitamin D. Another paper took things a step further, and showed that even when their skin is exposed to sunlight, carp and halibut still require most of their vitamin D from dietary sources. Numerous other papers in the Science Direct database reported the absence of vitamin D synthesis in a variety of fish species.

All of that suggests that even the best natural dietary source of vitamin D we know of is itself getting its vitamin D from diet, but where? Well, maybe plankton. This paper reported that, during summer months, plankton contain high amounts of vitamin D.

Ultimately, it would appear the review we are all looking for is this one , which also argues along the plankton route (yay, one that's actually free to read finally). The argument is made in terms of the ecological pyramid. Basically, since 1000 pounds of plankton needs be consumed at the bottom for one pound of seal to be made at the top (or 10,000 pounds of plankton if you're making a pound of whale), even this seemlingly insignificant organism might much of the oceans' vitamin D through sequestration and concentration as this vitamin makes its way up the food change.

Then again, it's still not clear what the heck plankton itself uses the vitamin for, but it has been suggested to function as a UV filter. Someguy1221 (talk) 06:41, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Eh, a teeny bit more since I just realized I still haven't precisely answered the question. Various lines of research indicate that even in extreme northern regions, for at least some portion of the year there is enough sunlight for vitamin D synthesis. Furthermore, since the vitamin D cycle in these regions seem to be plankton→fish→predators, in addition to de novo synthesis in land animals (e.g. humans), even an inefficiently low rate of vitamin D synthesis can potentially provide all the vitamin D for the ecosystem thanks to the effect of the ecological pyramid. Finally, since vitamin D is fat-soluble, it can be efficiently absorbed and concentrated from dietary sources, and stored for long periods of time. Someguy1221 (talk) 09:33, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- just to clarify in reality it's more like plankton(algae)→plankton→plankton→fish→fish→predator this will allow the fat soluble vitamin to reach high concentrations through biomagnification as Someguy pointed out in his previous post. In fact polar bear and seal livers can have toxic quantities of Vitamin A. See Liver_(food). Staticd (talk) 17:39, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

Thanks everyone for all the responses so far! Count Iblis (talk) 16:10, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Liver (food) was wrong. The reference it uses, The vitamin A content and toxicity of bear and seal liver, to say seal liver is poisonous and not eaten by Inuit does not support that. What the reference says is that a particular seal, the "Phoca barbata" or bearded seal (see Otto Fabricius and the Seals of Greenland), has a liver that is high in A. It's not referenced but the bearded seal article says that it is the main diet of polar bears. Other than that seal liver is eaten, see Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia, Volume 1 or Visual theses: Inuit art: eco-centric imagery or imaginary Inuit?, the first one points out that bearded seal live is not eaten. By the way one report suggests that seal liver contributes to vitamin C in the Inuit diet, Vitamin C in the Diet of Inuit Hunters From Holman, Northwest Territories. Also I haven't read Age differences in vitamin A intake among Canadian Inuit yet but there might be something interesting in there. CambridgeBayWeather (talk) 17:23, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- This article describes dietary sources of vitamin D (specifically opposed to skin/fur based production) [1]. I found some books that say UVB is required for vitamin D production in fish too (ISBN 0813814014 page 64). There's also a fascinatingly in depth book about Vitamin D entitled..... Vitamin D, by David Feldman, J. Wesley Pike, John S. Adams (ISBN 0123819784). It is apparently possible to produce Vitamin D synthetically completely absent of sunlight/irradiation (ISBN 0412780909) but I didn't see anything saying that it exists in the natural world. This line was especially interesting: "It has been estimated that approximately 10-15 min of summer sun exposure of hands and face will produce...sufficient [vitamin d3] to meet the daily requirement."

- But I also think it's a mistake to equate the 30 degree figure that may apply to mammals or vertebrates to plankton and other basic food aquatic food sources. It's quite likely those organisms are more effective at synthesizing vitamin d than mammals. Shadowjams (talk) 04:04, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Folks are also forgetting migration. Not all of the arctic animals live there year-round. — The Hand That Feeds You:Bite 22:24, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- I mentioned it back on 06:14, 6 May 2012 (UTC). StuRat (talk) 17:48, 9 May 2012 (UTC)

Oil near the Great Lakes

[edit]Approximately how much oil (petroleum) is drilled from the Great Lakes Basin a year? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 64.229.204.143 (talk) 04:10, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- On the Canadian side, the annual oil production for the province of Ontario in 2006 was about 150,000 m3 (~900,000 barrels), with a further 31 million m3 being the remaining potential, most in the Great Lakes area [2]. Mikenorton (talk) 07:46, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Note that Ontario isn't entirely in the Great Lakes Basin. StuRat (talk) 03:43, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- On the US side there is no oil production currently from the Great Lakes area and exploration drilling into the lake beds is currently banned. There was a little oil production in Michigan from wells drilled onshore, but these currently only produce gas with some limited liquids (~7,000 barrels in 2007) [3]. Mikenorton (talk) 08:10, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- There's oil in Ohio and Pennsylvania (this is one of the first oil fields found), but that may all be south of the GLB. StuRat (talk) 03:43, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

entanglement Logic

[edit]does the following logic make sense? If A is true and B is true,(as if entangled) then if A were not true, B would not be true. Or more specifically: because my son and i coexist, if my son never existed I would have never existed either.68.83.98.40 (talk) 05:02, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- It does make sense if you and your son are entangled. Plasmic Physics (talk) 06:06, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- If you do not assume that you and your son are entangled but still hold that A therefore B ⇒ Not A, therefore not B, then you are denying the antecedent, a logical fallacy. Someguy1221 (talk) 06:47, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

The logic is not A therefore B, but A AND B experienced TOGETHER then not A therefore not B. See the difference?68.83.98.40 (talk) 12:38, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- You may find the article Logical connective to be informative in this sort of discussion. --Jayron32 12:47, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think entanglement (which is several concepts in theoretical physics) has anything to do with abstract logic. But if by "entangled" you just mean

A ⇔ B

then indeed

A ⇔ B and ¬A implies ¬B

Ok then my question is really: Does "my son and I coexist" = "A ⇔ B"?165.212.189.187 (talk) 12:39, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Only if you were born at the same time. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 12:52, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

Then how would you express "my son and I coexist"?165.212.189.187 (talk) 15:33, 7 May 2012 (UTC) I didn't know I had to be so specific: You mean the exact same second or planck time? Isn't time relative anyway?165.212.189.187 (talk) 13:15, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Your son's existence depends on your having existed to be the father. Your existence does not depend on his existence. You would exist whether or not you had a son. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 22:20, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

That is awfully presumptuous, how do you know? my only reality has a son at some point in my existence. Ok that is the superficial pitfall. It doesn't have to be relatives. It could be "you and I coexist". My point is that it is unfalsifiable because we both DO exist. So you can't know what would happen if one of us never did.68.83.98.40 (talk) 02:49, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- If you assert that it's impossible for A∩B to be false, then any conclusion on the consequence of A and not-B is a vacuous truth. Someguy1221 (talk) 02:57, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

It's really about the conservation of matter/energy. Because I do exist, if I didn't then that would mean that matter would be destroyed and violate the conservation law — Preceding unsigned comment added by 68.83.98.40 (talk) 03:19, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- No it wouldn't. Your atoms and molecules existed before you were alive, and they'll exist after you're gone. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 04:04, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Lol. That is exactly what I am saying. I am "my atoms" and my atoms are me!68.83.98.40 (talk) 04:52, 8 May 2012 (UTC) That negative narrow-mindedness is precisely what is wrong with the scientific establishment. Blurting "no it wouldn't ". Without even trying to understand another pov.68.83.98.40 (talk) 04:59, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- So what's your goal here, 68? Someguy1221 (talk) 04:59, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- This is a philosophical question, not really science. On the one hand you could argue that since A is definitely true (you do exist) then "not A implies not B" is a true statement (as Someguy1221 mentioned). "Not A implies C" is true for any C. However usually when we make a conditional statement like this we're trying to say something about what's "possible" in some sense of that word. Is it possible for you to have existed and for your son not to have existed? What does this question actually mean given that you do in fact exist? If you subscribe to modal realism then the question makes perfect sense. In that case the statement A is probably not universally true, and we can ask whether there are some versions of the universe without A but with B. But then we have to examine what it means for "your son to exist". How should we define what counts as "your son" in various different universes. Now this gets into questions of identity which is a headache. Rckrone (talk) 05:05, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Not really. I was using the father son relationship to show that I was not talking about causality. A is NOT I exist it is my son exists ok? B is I exist, so please stop focusing on the chicken and egg thing. Here it is : something exists. And BECAUSE it does exist if that something ceased to exist everything would cease to exist.68.83.98.40 (talk) 05:18, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Why would everything cease to exist? Someguy1221 (talk) 05:28, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Because you cannot separate the something from the everything. The something is what makes the everything everything.68.83.98.40 (talk) 05:32, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Nothing I said has anything to do with causality. I don't know what "chicken and egg thing" you're talking about.

- I also have no idea what you mean when you talk about a thing ceasing to exist. Are you trying to say that the universe can't exist in any way except exactly as it does, maybe because of some notion of determinism? Rckrone (talk) 05:39, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Kinda. But not really anything to do with determinism. Btw You inverted a and b re: chicken thing.68.83.98.40 (talk) 05:43, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- 68, the problem with that way is thinking is not that it is wrong, but that it's useless. You've constructed a system of logic in which nothing meaningful can be proven because you're declared that only the only possible world is the one that currently exists. Someguy1221 (talk) 05:44, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Ok. Aren't I also declaring that if someone/thing were to just disappear ie cease to exist that that would have serious effects on the universe?68.83.98.40 (talk) 06:06, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Without having explicated the consequences of your disappearance, you are declaring them to be "serious" nonetheless. Someguy1221 (talk) 06:22, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Oh, right, in my place forms a giant black hole that swallows up the entire universe.165.212.189.187 (talk) 13:04, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

What percentage of human zygotes end up dying in the womb?

[edit]My question is: What percentage of human zygotes end up dying in the womb?

A little background: I remember that years ago back in high school science class I learned that the vast majority of human zygotes die in the womb. A very high percentage was given and I vaguely remember it to be around 80%. Out of random curiosity I tried to find that percentage today and to my shock the answer didn't come easily. A whole range of numbers from 30% to 90% were thrown around in yahoo answers and blog posts with no citation to back them up. I have zero medical training so I'm unable to effectively search through PubMed or Google Scholar because I don't know the right keywords.

Clarifications: I phrased the question as clearly and unambiguously as possible but miscommunications are still possible so I'd like to clarify what I'm not looking for:

- I'm not looking for data on embryo or fetus. By definition the survival rate for zygotes is lower or equal to the survival rate of embryos which is in turn lower or equal to the survival rate of fetuses. I'm only interested in survival rate for zygotes, which is the "worst case rate" that factors in the survival rate of embryos and fetuses.

- I'm not looking for miscarriage data. Multiple zygotes can die in a woman and she can still have her normal period within the same month; there is no miscarriage in this case.Anonymous.translator (talk) 12:45, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- A zygote that dies very early on will usually not leave any signs that conception ever took place, which makes it very difficult to get accurate numbers on how often it happens. That's probably why you couldn't find an definite answer. --Tango (talk) 14:23, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Like Tango said, this is very difficult to determine, however, this article could be interesting in this context. It suggests that the maximum chance of (clinically recognized) pregnancy (30-40%) is (mainly) determined by the rate of preclinical pregnancy loss. That is to say, probably most of the 60-70% of women who fail to conceive in optimal conditions experience early pregnancy loss. Combined with the rate of clinical spontaneous abortion of 8%, one could estimate that (1-0.4*0.92=0.63; 1-0.3*0.92=0.72) 63-72% of fertilized eggs die in the womb, but this assumes a 100% conception rate in optimal conditions, which is probably lower. - Lindert (talk) 14:46, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Thank you for your responses. Yes, I realize getting an accurate measure of this is very hard, but I'm content with any rough estimates (as long as it appears in a peer-reviewed medical journal).

- Lindert, if I'm not mistaken, your calculation makes the implicit assumption that only one zygote can be in the womb at any given time. Please imagine case A where 10 eggs are fertilized in a womb and none of them failed to implant. Your calculation will count that as one single early pregnancy loss while I count 10 zygote deaths. Also please imagine case B where 10 eggs are fertilized in a womb and only one of them managed to achieve implantation. Your calculation will count that as one surviving zygote while I count one surviving zygote and 9 zygote deaths, a 90% zygote death rate.Anonymous.translator (talk) 21:58, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- This situation does not happen in humans. During ovulation, only a single egg, and occasionally two eggs are released from the ovaries. After ovulation, the unfertilised eggs survive only one or two days. If fertilized, the egg(s) will prevent a subsequent ovulation and if not, they die. This means there are never more than two living eggs in the womb, so no more than two can be fertilized at the same time. In most situations there is only one. - Lindert (talk) 23:47, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- As a minor quibble, at least three is possible: I myself am acquainted with a set of non-identical triplets. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.197.66.211 (talk) 14:35, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Thanks for the correction, I did not know that. In light of this I phrased the question incorrectly. I meant to count the case where a zygote split into multiple embryos and the embryos die as "zygote deaths". Essentially each zygote can have "multiple deaths" if it's subsequently split. Anonymous.translator (talk) 00:05, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- What you are talking about is how monozygotic twins occur which happens at a rate of about 3 in 1000 births. So even if they have a better then average chance of miscarriage, which is possible, they won't skew the numbers very much. Vespine (talk) 03:02, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- This situation does not happen in humans. During ovulation, only a single egg, and occasionally two eggs are released from the ovaries. After ovulation, the unfertilised eggs survive only one or two days. If fertilized, the egg(s) will prevent a subsequent ovulation and if not, they die. This means there are never more than two living eggs in the womb, so no more than two can be fertilized at the same time. In most situations there is only one. - Lindert (talk) 23:47, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

Virtual work

[edit]Are there any situations, even very contrived situations, where constraint forces do virtual work? 65.92.6.118 (talk) 15:03, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Do you mean like Gold farming and Virtual economy? Unique Ubiquitous (talk) 17:54, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I suspect the original poster means virtual work. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 18:25, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Right, science section... well that question goes over my head that's for sure, Unique Ubiquitous (talk) 20:01, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I suspect the original poster means virtual work. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 18:25, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Goldstein says "We now restrict ourselves to systems for which the net virtual work of the forces of constraint is zero ... This is no longer true if sliding friction forces are present, and we must exclude such systems from our formulation." (Classical Mechanics 1980, p17). Gandalf61 (talk) 08:40, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Hmm, how is sliding friction a constraint force? 65.92.6.118 (talk) 22:57, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- In the case of zero acceleration (i.e. static case), but non-zero movement. --145.94.77.43 (talk) 01:13, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Hmm, how is sliding friction a constraint force? 65.92.6.118 (talk) 22:57, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

Is it safe to keep batteries in a tin can?

[edit]I keep my batteries in a red tin can and a brown tin can. I put the dead ones in the red can and the ones that I haven't used yet in the brown can. After a while this chemical smell started come around. So is this safe? Oh and can I recycle batteries? Matthew Goldsmith 18:58, 6 May 2012 (UTC) — Preceding unsigned comment added by Lightylight (talk • contribs)

- What kind of batteries? Whoop whoop pull up Bitching Betty | Averted crashes 19:15, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- That's a bad idea. Tin cans (which are usually made of steel) conduct electricity, so your batteries could become shorted and run down. I keep mine in a plastic container. Many of the materials can be recycled. See battery recycling.--Shantavira|feed me 19:17, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- They could short, if they are PP3's or something else with the contacts on the same end, but for ordinary AA's and the like, it is hard to see how an accidental short is going to occur. --ColinFine (talk) 22:34, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- The smell could be from chemical reactions caused by retained air moisture, if you have lids on the tins - say push-fit lids that seal. If you open and close the lid during the day (to add or remove a battery), the air in the tin will be the same as the air outside, which has a certain himidity, that is, a certain moisture content. Overnight, the temperature drops, causing condensation inside the tin. If the condensed water then reacts with the battery materials and/or inside the tin, moisture is removed from the air within the tin. Next time you open the tin, that moisture is replaced, further driving the reaction during the night. If the lid is a quite good seal, but not a perfect seal, the daily temperature cycle can drive the same sort of effect without you opening the tin. When cool, moisture is condensed and reacts with the contents. The tin air moisture partial pressure will be then low when warm, sucking in more moisture from the outside. As you probably open it only during the day, you never notice any wetness from condensation, just the smell from the corrosion. Ratbone121.221.215.60 (talk) 01:34, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Some batteries leak out acid and such when they fail. While this isn't exactly dangerous (unless you store the tin can above your head while you sleep so it can drip acid into your eyes after it rusts through the can), it could make a mess, so I agree with the plastic can suggestion. StuRat (talk) 03:34, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- It's not usually acid. It's potassium hydroxide in most alkaline batteries. Shadowjams (talk) 03:38, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Perchlorate ion electronic structure

[edit]

Is the perchlorate ion composed of a chlorine atom with double bonds to three oxygen atoms and a single bond to one negatively charged oxygen atom, isoelectronic with perchloryl fluoride, or a negatively charged chlorine atom with double bonds to four oxygen atoms, valence isoelectronic to xenon tetroxide? Whoop whoop pull up Bitching Betty | Averted crashes 20:58, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- It is more like a 1.75 order bond. All the oxygen bonds to chlorine are symmetrical, with negative charge distributed over them all. Xenon is further down the table so I would not call it isoelectronic. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 21:29, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I like to think of the perchlorate anion as having only one true single bond equally shared between all four oxygens. Despite the oxygens not having a full octet each, they have attained a lower ground state by spilling their HOAOs over onto chlorine, producing dative bonding. They borrow the empty LUAOs of chlorine to do this, chlorine doesn't like this configuration, but oxygen has the veto power in this case, because the net effect is a lower ground state. This is why it is such a good oxidising agent, chlorine is stretched out of its comfort zone, and oxygen does not have a full octet - a relationship which is easily destroyed, releasing oxygen free radicals and hypochlorite. The unpaired electron is paired with a foreign electron equally shared by all the oxygens, since they are all degenerate. This is just how I like to look at it. Plasmic Physics (talk) 22:08, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- I'm not sure that agrees with the statement in the perchlorate article that the chlorine atom has a closed-shell configuration. And I think it contradicts the dicsussion of reactions being kinetically slow because the chlorine is blocked by the surrounding oxygens. Your description suggests that reactions would easily start because the oxygens are electronically unstable as well as being on the "outside" of the cluster. DMacks (talk) 01:06, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Maybe it is not so easily destroyed, I was thinking of xenon tetraoxide when I wote that comment. Anyway you look at it, chlorine will have more than 8 valence electrons. It's not the chlorine that reacts in the perchlorate ion, it's the oxgens. Although the oxygens only have 6.5 electrons each, they are more stable, but less so than if they had 8 electrons each. In order to react, they dative bond has to be severed first, and they are hidden within the molecule. The kinetic rate is dependent on the reaction mechanism, which I did not discuss. Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:40, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- The stability of 6.5 electron oxygens are demonstrated by the explosive thermal decomposition. Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:43, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- I'm not sure that agrees with the statement in the perchlorate article that the chlorine atom has a closed-shell configuration. And I think it contradicts the dicsussion of reactions being kinetically slow because the chlorine is blocked by the surrounding oxygens. Your description suggests that reactions would easily start because the oxygens are electronically unstable as well as being on the "outside" of the cluster. DMacks (talk) 01:06, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- It's like inn keeper and his inn (chlorine) he has one paying guest (oxygen). Then arrives a three of guest's brothers, they are broke. inn keeper doesn't like the situation of having them staying for free, but because it is winter, he lets them stay, all four brothers are given four seperate rooms which are priced the same. The three can easily overstay their welcome, they are only guests after all. Plasmic Physics (talk) 22:26, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- There are a bunch of molecular orbitals that can be displayed by a Java applet at http://www.chemeddl.org/resources/models360/models.php?pubchem=104770 (incredibly, this particular Java applet actually works! How often does that happen?) Wnt (talk) 01:28, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Firefox had a problem and crashed. We'll try to restore your tabs and windows when it restarts. :-/ Ssscienccce (talk) 17:12, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- There are a bunch of molecular orbitals that can be displayed by a Java applet at http://www.chemeddl.org/resources/models360/models.php?pubchem=104770 (incredibly, this particular Java applet actually works! How often does that happen?) Wnt (talk) 01:28, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

dripping under sink

[edit]I have noticed occasional dripping noises under my bathroom sink sometimes when I turn on the water I will hear dripping noises underneath the sink when I look underneath the sink there is no water dripping out the pipe that is visible to me. Sometimes there are no dripping noises even when the water is running for a while. What is the cause of this probably?--Wrk678 (talk) 21:01, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Maybe you're splashing water onto the counter and it's dripping down somewhere else? Wnt (talk) 01:20, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Wnt has given the most likely cause. If not, maybe there is a leak inside the wall, or something is trapped in the U-bend, causing water to drip into air sapce behind it. Ratbone121.221.215.60 (talk) 01:39, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- I've noticed the same thing in my shower, what happens there is that whatever residual water left gathers at the bottom of the sink and then drips off the middle of the little grating in the plug hole into the water in the S bend. Then the water flowing past the s bend might then also make a dripping noise inside the pipes, but it's hard to imagine how it would make a noise unless there's some dirt build up or a poor plumbing joint causing the water not to just flow down the side of the pipe silently . Vespine (talk) 02:55, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Wnt has given the most likely cause. If not, maybe there is a leak inside the wall, or something is trapped in the U-bend, causing water to drip into air sapce behind it. Ratbone121.221.215.60 (talk) 01:39, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- It's not unusual for the pipes to make "tic" sounds when the flowing water cools them down, causing contraction (or the opposite when using hot water). Can sometimes sound like dropping water, happened to me once, looking for a leak that wasn't there. Ssscienccce (talk) 04:06, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- The O-ring seals of many faucets wear down with usage (hardware stores sell replacement seals for a couple of dollars) and which often initially causes a very slow and intermittent leakage that can be hidden and/or very difficult to see when the water film adheres to the backside of one of the pipes as it runs to either behind the wallboard or under the floorboards, where the water accumulates into droplets and drips unseen. Of course, with the faucet running, you can check for any unseen wetness under the cabinet by grasping the pipes with your hands or with tissue. Also, depending on your type of faucet, its possible that a plastic valve stem is cracked, due to deterioration, and/or from having had too much force applied to the handle. --Modocc (talk) 14:28, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- At my house, my air conditioning drain line (for condensation off the coils) runs into the pipes under the sink. Sometimes I can hear it gurgling or dripping into the pipes. Do you have any additional pipes or lines under the sink? Tobyc75 (talk) 00:44, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Perhaps other pipes could explain the noise, but this seems unlikely if the OP notices the dripping during faucet usage only and not during other activities. Although the dripping noise may be nothing more than drain pipe noise as has been suggested or the result of splashed water, slow leaks are sometimes not only hard to detect due to the thin films these create, they are often intermittent too for various reasons, such as the leaky seal slowly repositioning itself due to the water flow thus stopping the leak with continued usage, or, for another example, when water debris temporarily seals the leak. --Modocc (talk) 20:14, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- At my house, my air conditioning drain line (for condensation off the coils) runs into the pipes under the sink. Sometimes I can hear it gurgling or dripping into the pipes. Do you have any additional pipes or lines under the sink? Tobyc75 (talk) 00:44, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

Fractional degrees of freedom

[edit]The article Cosmic neutrino background assigns fermions 2*(7/8) degrees of freedom each. How can it have fractional degrees of freedom? RJFJR (talk) 21:24, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- Limitations due to the Pauli exclusion principle can reduce the mean degrees of freedom in a population of fermions. I have no idea how they come up with 2(7/8) in this case. 71.215.84.127 (talk) 00:21, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Looking hard enough, I can find papers that mention various thermodynamic quantities as having fractional degrees of freedom, but seem to assign the "fraction" bit no significant, as they make no effort to explain it. It seems to just pop out of the equations in certain circumstances. As for fractional degrees of freedom themselves, there appear to be many math papers on the internet that discuss how to handle fractional degrees of freedom in statistics. Now, as you probably already discovered, the cite for the 2(7/8) value came from a book, and I can find no other citation for that fact, so if you really want your curiosity sated, you may have to visit a library. Or BenRG will do the calculation right here or something. Someguy1221 (talk) 01:21, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Give me your teeny tiny masses yearning to be fractionally free. Clarityfiend (talk) 21:56, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

I think the derivation is given in http://www.osti.gov/bridge/servlets/purl/532665-UP3Y1y/webviewable/532665.pdf , though understanding it is another matter. ;) This is the "canonical fermion factor of 7/8".

"The energy of unpolarised particles in the phase space volume is

where n is the mean occupation number for either photons or neutrinos. h is Planck's constant. The entropy of that same volume is

- (for neutrinos)

- (for photons)

Where k is Boltzmann's constant."

The + and - eventually lead to a 15+-1/16 expression, which is 2 for bosons and 1 for fermions.

Of course, this is not exactly what I think you meant when you said "why"! :) Wnt (talk) 18:30, 10 May 2012 (UTC)

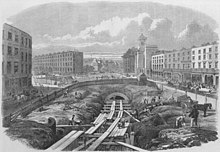

Metro lines and building

[edit]How are underground subway lines built under existing buildings? For example, I know that some of the sections of London Underground lines follow streets, but there are some sections in the Victoria and Circle lines that seem to go right underneath residential areas. How do they build those without affecting the houses above? Also, if you live in a house like that, can you hear and feel the trains?71.229.194.243 (talk) 23:50, 6 May 2012 (UTC)

- There are two types of tunnel in the London Underground; the older ones that follow steets tend to be cut and cover tunnels, where they dig a channel, make a roof over the top and the roadway goes on the roof. The slightly newer ones are deep level tunnels made by boring through the ground. They are so deep that (in theory at least) they don't affect the buidings at ground level - the WP article says about 20 metres below the surface on average - the deepest is 61 metres. Alansplodge (talk) 00:12, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- You can be fooled. In my city, we have rail and freeway tunnels. Only about 100 m was done by tunneling - the remainder was all cut and fill. But a lot of the cut and fill (what was not done by digging up streets) was done by demolishing houses first. Then when the tunnel work was done, they built new shops and dwellings on top of the tunnel. They routed the tunnel to give an additional benefit - they got rid of some old inner city slum houses by government compulsory resumption and replaced them with nice new buildings. The roof of the tunnel appears to be about 2m below the natural surface. Inside the buildings on top, you cannot detect the traffic. Ratbone121.221.215.60 (talk) 01:49, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Regarding your second question, I used to live right above the Central Line in Bethnal Green and we could hear the rumbling trains beneath but not really feel them. The line is quite deep there, but it does follow the road for the most part. Bear in mind that numerous access shafts are required for construction, so following an existing road is desirable even when it's not necessary. Modern construction methods involve minimal disruption at the surface.--Shantavira|feed me 08:19, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- As to the first part of your question - how does the excavation not damage the buildings above? If the engineers don't take active steps, it certainly can.

- The cut and cover tunnels that Alan linked to above are essentially large trenches. Like any trench, if you leave the sides alone they'll quickly collapse in. This undermines the adjacent soil, and risks the foundations of nearby buildings. So the tunnel engineers have to make up for the support that was previously supplied by the ground that they've taken away. Typically they build vertical retaining walls to line the trench, and then brace these against one another with horizontal steel beams (or in places that are wide enough they might use steel buttresswork).

- For deeper tunnels, a circular cutting disk called a "tunnelling shield" is used. Long ago this was just a frame on which workers stood, from where they wielded hand tools - but now it's a rotating disk with a bunch of cutting wheels attached to it. In modern times the shield is the fore part of a whole tunnelling machine called a tunnel boring machine (TBM). A TBM powers its own shield, disposes of the extracted "muck", and inches itself forward with hydraulic jacks into the space it has cut. With every step it moves, like a giant metal worm, through the ground, leaving a circular tunnel tube behind it. But again the tunnelling has removed a bunch of material from the ground, which formerly supported the ground above. Eventually the tunnel will collapse, undermining these (fracturing gas pipes and sewers, breaking electrical and communication lines, and damaging buildings and other structures). So, for all but the hardiest rock (which engineers don't like to dig through, because it's such slow going) they have to line the tunnel with supports that take up the load. For a cylindrical bore like this, the load is usually carried by precast steel-reenforced concrete lining elements that slot together to line the tunnel walls. A TBM has a mechanism to bring these forward, place them against the fresh surface, and secure them in place (depending on the kind of ground that might need grout and/or metal anchors). Once the wall is secured by these liners the tunnel can sustain the pressure from the ground forever (as long as the liner elements are maintained). But there's still a problem - the liners are fitted by the back end of the TBM (in fact it's the fitted liners than the TBM pushes against to advance itself). The ground around most of the TBM's body has to be held up by the TBM itself. That still leaves the shield and the space behind it (which is full of drilling mud and air); if the material through which the tunnel is going is soft and particularly if it's wet then this space alone can sag, fouling the machine and causing subsidence above. The solution is to pressurise the cutting space to counteract the ground pressure. This used to be done with compressed air - a pressure dam was constructed behind the TBM and the whole TBM space was pressurised (sometimes to as high as 3 or 4 bar). But this meant human workers had to work in this high pressure environment, which is difficult, unpleasant, unhealthy, and potentially very dangerous (if the pressure leaks unexpectedly). So many newer TBMs use a pressurised mud system instead, where only the shield and the space immediately behind it is pressurised. With this (very clever, but complicated and expensive) mechanism in place the load of the ground is resisted throughout the tunnelling process, so there shouldn't be any subsidence. Occasionally this isn't enough, however. In some places (I think e.g. in Singapore when they build a long water-carrying bore) engineers discover that the ground is fractured such that in a few places it can't sustain the shield pressure - the TBM will dig along until it hits such a fissure, and the pressure in the shield will fall to 1 bar as the overpressure escapes through the fissure to the surface (which is probably quite scary for anyone near the fissure when it blows open on the surface). In cases like this they have a team of workers on the surface who drill into the ground (they know where the fissure is, because surveyors know where the stalled TBM is). These workers inject the ground with quick-setting grout that seals the fissure. This allows the TBM to get back up to pressure, so it can advance again. Given the high costs of TBM operation (and thus the high costs of a TBM being stalled) I imagine these guys are pretty aggressive about drilling those grouting holes: I'd really like to know how they coordinate things so the grouting team has prompt access to somewhere close enough to the fissure that they can get the grouting done in a short time. If everything goes fine there should be no great evidence on the surface that a TBM tunnel is or has been cut (bar the few places where surface grouting is necessary). But managing the shield pressure properly is difficult, because the TBM passes through different layers of soil, sand, grit, and mud as it digs, and different pressures are needed. Too little pressure and the ground sags, too much and it heaves up. This report, about a tunnel at London's Heathrow Airport, talks about heave due to mud pressure overages in the shield, followed by subsidence behind the TBM as the ground relaxes onto the lining. They talk about deflections at the surface of around 20mm. Any building foundation has to withstand a degree of heave and sag due to soil hydrology and temperature, but 20mm is more than I'd expect in a temperate climate, so if that particular tunnel had gone under someone's house they'd have to yell at the contractors and get them to do some additional shoring and grouting at the surface to prevent the house's foundation from cracking. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 17:07, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- This is all very interesting, except... what difference does 2-3 bar make to soil deep underneath the ground? I understand that 10 meters of water = 1 bar, and soil/rock is probably twice as dense. Wnt (talk) 20:38, 9 May 2012 (UTC)

- I found this engraving of the construction of cut-and-cover tunnels for the Metropolitan Railway in 1861. I also found a photo of the later deep tunnels in the making; Three labourers work within the cylindrical frame of a Greathead Shield during the construction of the Central London Railway (now Central line), near Tottenham Court Road Station, Dec 1897. Alansplodge (talk) 20:04, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- See also "Seattle Underground".—Wavelength (talk) 20:14, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

Finlay, I only understand about half of that answer but thanks. It is a marvel how they were able to build those tunnels before the advent of Tunnel Boring Machines. But, maybe I should rephrase my question slightly: Did they tear down and put up new houses when the deep level tube lines, as opposed to subsurface lines which use more cut and cover, were being built, or were they able to use the tunneling shield under existing residences, which seems possible if they are really 20 meters below surface? 71.229.194.243 (talk) 22:58, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, with a deep bore they could avoid the costs of disturbing surface properties, underground utilities, and surface transportation. That's often enough of a saving to pay for the increased cost of a shield boring operation. The calculation of which to do depends on the values of the stuff above (and the political clout of the people who own it) vs the character of the geology (some places, and some layers, are more practical to bore through than others). -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 23:04, 7 May 2012 (UTC)

- In New York City I lived directly above the Brooklyn end of the Rutgers Street Tunnel, which goes under the East River. I'm not sure how deep under the ground it was below my place, but it couldn't have been too far since the station was just a block away--and while it was a deeper station than some, it wasn't that deep. In my building you couldn't really hear the trains--maybe very faintly if it was quiet (trains going over the nearby Manhattan Bridge were far louder)--but you could feel a mild rumbling/vibrating, especially when, say, lying in bed. I'm not sure how the tunnel was built. I think it was done around 1930, and most of the buildings above it, like mine, were older than that. It would appear that they were able to build the tunnel without needing to take out the surface buildings. Pfly (talk) 07:28, 8 May 2012 (UTC)

- Also, have a look at the new London Crossrail project which is being driven under the buildings of the capital as we speak - it will accomodate full sized main line trains, not little Tube trains. Alansplodge (talk) 23:50, 10 May 2012 (UTC)

![{\displaystyle 2k[-(1-n)\ln(1-n)-n\ln n]{\frac {d^{3}pd^{3}r}{h^{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/75d6900d591e75089a9ecb505075aecdb4803780)

![{\displaystyle 2k[+(1+n)\ln(1+n)-n\ln n]{\frac {d^{3}pd^{3}r}{h^{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1bc6f08cdc0f0aed9e141778367c1f9cf037fdb1)