Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2011 July 1

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < June 30 | << Jun | July | Aug >> | July 2 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

July 1

[edit]Fungus that looks like rags

[edit]I have a fungus in my backyard that looks like old rags. It tends to grow near a tree. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 74.229.224.168 (talk) 00:09, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm surprised it doesn't grow in the garage next to the rag pile. :-) But, seriously, we really need a pic to identify it. StuRat (talk) 00:20, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Does it look anything like this?

- Here" is a collection of Google search images for "fungus on tree". Bus stop (talk) 00:53, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Black hole

[edit]If matter is never destroyed (just changing form), once matter enters a black hole, and then the black hole evaporates, what happens to the matter? Albacore (talk) 00:48, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The matter is converted into Hawking Radiation. But from Mass we learn that "all types of energy have an associated mass" and it is mass, not specific matter, which is preserved. --Tagishsimon (talk) 01:05, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The answer might be different if you use "matter" in the narrow sense of "opposed to antimatter". The notion of using a microscopic black hole to catalyze the conversion of matter to energy (i.e. equal parts matter and antimatter) is most appealing, though certainly not safe, yet I've heard people doubt the possibility. Wnt (talk) 16:22, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Your comment above is unclear. would you mind clarifying it? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.101.45.227 (talk) 20:44, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Name of our Black Hole

[edit]What is the name of the Black Hole at the center of our galaxy and how long will it take before our sun and the Earth spiral in are consumed? --DeeperQA (talk) 10:59, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- First question: Sagittarius A* --George100 (talk) 11:05, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Second question: Not before other things happen to the Sun and the Earth which render the question moot. --Jayron32 12:04, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The solar system is in a stable orbit around the center of the Milky Way galaxy, black hole included, not spiraling in, any more than the Earth is spiraling in to the Sun. StuRat (talk) 18:14, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Black holes do, however, tend to sink towards the centers of galaxies. This article claims there may be 10,000 black holes swarming around the central supermassive one:

When such a massive object flies by one of the greater number of less massive stars, the lighter body gains speed while the heavier body loses speed. Several such two-body interactions make heavier bodies fall towards the galactic centre, while lightweight stars are ejected towards the outer regions of the galaxy. - "Signs that black holes swarm at galaxy centre"

- It's not clear whether these multiple black holes eventually merge into the central one. --George100 (talk) 20:13, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Black holes aren't necessarily any heavier than average stars. When a large star goes supernova it sheds its outer layers, so the bit that collapses into a black hole is only a fraction of the original mass. --Tango (talk) 21:49, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if they were more massive, that alone isn't a reason why they can't have a stable orbit about the super-massive black hole at the center of the galaxy. StuRat (talk) 08:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, although they would tend to settle towards the centre of the galaxy in the way the source George quotes describes. They would be in a stable orbit still, just a close one. If they get close enough, though, gravitational radiation will cause their orbits to decay (as it does all orbits, but usually too slowly to be significant). --Tango (talk) 13:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if they were more massive, that alone isn't a reason why they can't have a stable orbit about the super-massive black hole at the center of the galaxy. StuRat (talk) 08:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- This makes me wonder about the growth rate of a typical stellar black hole. Since it's a stellar mass within a tiny radius, it would continually consume the interstellar medium, or if it's paired with a star it would consume a significant part of that mass. Still it seems that it would take considerable time for one to grow substantially larger than its original size. --George100 (talk) 12:27, 4 July 2011 (UTC)

Atomic weight notation

[edit]What is the meaning of the numeral in parentheses following an atomic weight? In the List of elements article, each weight is followed by a second number, such as Hydrogen - 1.00794 is followed by (7), or Lithium 6.941(2). I can't find an explanation in the Atomic weight article either. --George100 (talk) 11:03, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I've seen that in tables of physical constants before. I've always assumed that it means the digits in parentheses are uncertain. --173.49.9.250 (talk) 11:23, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- 173 has it correct. When you see a number listed with the last digit in parentheses, that is the digit where the uncertainty occurs. Ideally, somewhere in the same publication (perhaps in the introduction or the addenda, or maybe as a footnote or something like that) is an explanation "Values have an uncertainty of +/- x%" and this uncertainty means that the last quoted digit is kinda "fuzzy". This is expecially true for quoted values of atomic weight, since these values are usually (unless otherwise noted) values for average atomic weight of all known isotopes of the element, weighted for their natural abundance. Since there is some uncertainty in natural abundance levels, there is going to be some uncertainty in the average atomic mass, via Propagation of uncertainty. --Jayron32 12:02, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- See Uncertainty#Measurements and http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Info/Constants/definitions.html. 0.123(45) is a shorter way of writing 0.123 ± 0.045. The parenthesized digits aren't uncertain, they're the uncertainty. -- BenRG (talk) 17:58, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Just to emphasize, BenRG's explanation is correct, not the first two (though they were sort of correct). The digits in parenthesis denote the uncertainty in the previous digits, so 0.04336(3) is equivalent to 0.04336 ± 0.00003 and 2.1540(35) is equivalent to 2.1540 ± 0.0035. Just saying that something is uncertain is pointless unless you say how uncertain it is.-RunningOnBrains(talk) 20:06, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Space Time

[edit]We know that Space time grid can be bend and folded.But I read somewhere that it can't be cut into pieces.Is it true??? Thank You — Preceding unsigned comment added by 117.197.254.243 (talk) 13:56, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The first question I would ask would be "what could possibly separate the pieces?" Dbfirs 17:47, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- General relativity requires spacetime to be smooth, meaning that if you look at it at a high enough magnification, it looks like uniform flat spacetime extending in all directions. A cut in spacetime wouldn't qualify, because no matter how far you zoom in, that cut is still there. But general relativity can't be the end of the story. It seems possible (likely, even) that "cuts" of some sort will be permitted in quantum gravity. -- BenRG (talk) 18:01, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- One possibility is that black holes punch a hole in space time, perhaps leading to another point, such as the Big Bang, through a wormhole. This isn't quite the same as cutting space-time into pieces, though. StuRat (talk) 18:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Here's a hypothetical about a wormhole:[1] ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 20:49, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm not extremely fluent in cosmology, but cosmic strings appear to be kind of like a 1-dimensional rip (or at least a "crease") in spacetime. There is no evidence that they exist, however, and thus are just theoretical at this point. -RunningOnBrains(talk) 20:32, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

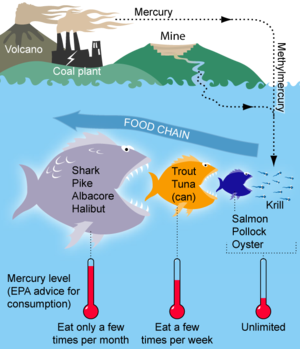

Mercury in sea fish

[edit]

How can some sea fish have high content of mercury? Any mercury which end in the sea or falls into a river would get diluded when it reaches the sea, even inside some organism. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Wikiweek (talk • contribs) 18:59, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- See Minamata disease in which mercury poisoning resulted from methylmercury pollution in Minamata Bay that affected both fish and shellfish. The concentration of mercury in the fish increased slowly by bioaccumulation, eventually reaching levels that were toxic. Mikenorton (talk) 19:08, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Fresh water fish is more contaminated than deep sea fish. Predatory fish and sea mammals - such as shark, swordfish, tuna and whale - are more contaminated than smaller fishes. Mercury accumulates up the food chain in a fish-eat-fish ocean. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 88.14.198.240 (talk) 19:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- There is little mercury in small young fish such as sardines. It is the large fish that live longer that accumulate more mercury. I think the increased levels of mercury in the sea was due to mercury being released into the air when coal was burnt, but I could be wrong. 92.24.141.227 (talk) 21:28, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The answer is Biomagnification. The water may dilute the mercury, but life can concentrate it just as fast.

- I've taken the liberty of adding the lovely illustration from the "Mercury in fish" article. APL (talk) 10:39, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- What about those lifeforms that eat the carcasses of large fishes? If none of the lifeforms excretes enough mercury so that in their body there is a lower mercury concentration than in their food, one would expect (in a closed ecology) that eventually, in equilibrium, the mercury concentration is the same in all lifeforms. There might be some lifeforms which accumulate more mercury at a certain concentration, but either the accumulation stops at a certain concentration or they continue to accumulate until they go extinct from mercury poisoning.

- So, the question is, is this higher mercury concentration in larger fishes a transitory phenomenon (under the assumption that the ecosystem is closed and "life" accumulates mercury that is inevitable)? I rather think there are at least bacteria which can excrete mercury efficiently from their cells (otherwise, wouldn't the accumulation have already happened over geological timescales? On the other hand, there is also sedimentation of organic material over geological timescales).

- So, the real question is: Which organisms accumulate mercury, and which don't?

- Icek (talk) 12:29, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

Maggots in my wheelie bin

[edit]Today while putting out my wheelie bin for its fortnightly collection, I was surprised to see a large mass of maggots writhing on top of the rubbish, in the juice from the remains of a mango. I do not waste food and care about hygene. How could the maggots have got there? Can they really grow from fly's eggs within 14 days? Could they have smelt the ripe mago and wriggled towards it? I had assumed they only liked animal material, not vegetable even if sweet. 92.24.141.227 (talk) 21:39, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- It takes less than a day for the eggs of a blowfly to hatch, so I don't think that this is a surprising observation. Mikenorton (talk) 21:53, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Have you ever wondered why a fruit fly are so named. For whatever food you eat there is some fly or insect that loves it too. Getting under your wheeliebin lid after detecting a mango would be routine for any fly that likes fruit. It would pop its eggs on or near the fruit and bingo. Richard Avery (talk) 22:02, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- According to Aristotle, it was a readily observable truth that aphids arise from the dew which falls on plants, flies from putrid matter, mice from dirty hay, crocodiles from rotting logs at the bottom of bodies of water, and so on. But in 1668, Francesco Redi challenged the idea that maggots arose spontaneously from rotting meat. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 22:39, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- You might want to use the method I use, mainly to control the stench. For things which will decay and stink before trash day, I employ a slop jar. This is typically an old coffee can. Since it seals tightly, no stink gets out and no flies get in. I have a ready supply, but you could reuse them by dumping the contents out and rinsing them on trash day, if you don't have enough. Alternatives to the slop jar include using a garbage disposal or flushing down the toilet. StuRat (talk) 23:37, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you are concerned about flies and other vermin attacking the contents of your wheelie bin, there are steps you can take to prevent it. If you have food waste collected on separate weeks to the other waste (as we do), you can get compostable plastic bags from your supermarket. Use these to wrap your food waste in. If you really can't put that bag into your all-purpose bin, you could put it into the freezer until the day before your food waste bin is collected then put it out in the bin. --TammyMoet (talk) 07:56, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Putting rotting vegetation in an air-tight container is a good recipe for anaerobic decomposition, which will produce enough methane to blow the top right off. A better solution is vermiculture, which is nearly odour- and maintenance-free and comes with the side benefit of producing rich, fertile soil for your garden or planters. SmashTheState (talk) 00:06, 6 July 2011 (UTC)

using the "scientific method"

[edit]I realize there is no ONE true "scientific method". So instead, I am interested in a range of possible approaches or methodologies I could follow to arrive at a measurement of the approximate percentage of people worldwide who are actually robots. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 188.29.154.125 (talk) 21:51, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ha! One place to start is by unambiguously defining what you mean by 'people', or more to the point, what constitutes a 'person'. This is no easy task! Google /problem of personhood/ to get an indication of the political, philosophical, and scientific issues involved. SemanticMantis (talk) 22:26, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec)While we're at it, we need a clear, unambiguous definition of robot. Once you have clear definitions, you should then set out a testing method to determine whether a subject meets the definition. Finally, you may want to read about statistical sampling to learn how many tests you should conduct in order to achieve a certain level of confidence in a conclusion about the large population. You will need to test somewhere between 0% and 100% of the population. Nimur (talk) 22:41, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think you're not understanding my question. It relates to the scientific method itself. If there were no robots or if there were a few, I would never find out the difference by the "statistical sampling" method you suggest. I need harder, realer science. And I need it yesterday, not tomorrow. As a compromise I will settle for later today.--188.29.154.125 (talk) 22:50, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Obviously I mean citizens. "Natural people" as far as the government, and other people, are concerned. Except they're really robots. --188.29.154.125 (talk) 22:40, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec)While we're at it, we need a clear, unambiguous definition of robot. Once you have clear definitions, you should then set out a testing method to determine whether a subject meets the definition. Finally, you may want to read about statistical sampling to learn how many tests you should conduct in order to achieve a certain level of confidence in a conclusion about the large population. You will need to test somewhere between 0% and 100% of the population. Nimur (talk) 22:41, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

The troll monicker is completely unwarranted. Why do I get it? Because it's "obvious" that "no one is a robot in all the nearly 7 billion people in the world". I would agree with that statement. However, "obvious" does not science make. This is an inherent question about the scientific method itself, with Robots just serving as an example of something that would require a paradigm shift. How does science deal with these situations? --188.29.154.125 (talk) 22:52, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- You could deal with the question if 'x does not exist in the group A' statistically. Test a reasonable number of members, and you can draw a conclusion (with a confidence interval). Quest09 (talk) 23:09, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

You guys are not understanding the question. I've removed the rude "troll" sign. Let me explain what some obvious problems are with the answers so far: How many 'people' have been outed world-wide as being really robots, to date? 0. Precisely 0. That means that out of 7,000,000 "people" not a single one has been shown to be a robot instead. Now you are proposing that I "test" people, to see if they're robots. But why would my test be any better than the fact that these "people" are tested every day by every single person they meet? Or, if these "people" don't meet anyone, then why would I be in a position to get to test them? I have other thinking, as well, about the scientific method. Take occam's razor. In order for there to be robots that have successfully passed for humans until my "test", that means that the true cutting-edge state of robotics must be well ahead the academic level. But what mechanism would put the true state of robotics so far ahead of the academic state? Occam's razor implies that the reason not one of the 7 billion "people" on Earth has been outed as being really a robot, is that none of them really are. But the question arises: is this reasoning correct? After all, there were millennia during which the heavenly spheres weren't outed as being "nothing at all", not existing period. It seems that I may have misapplied Occam's razor a moment ago, then, doesn't it? There is more. What if the robots are a conspiracy? Why would I be in any better a position than anyone else to find this out? I am asking a basic question about the world, just a scientist does who posits, say, in AD 300, that the moon orbits the Earth, the Earth and planets orbits the Sun, the sun and its solar-system interorbits with many other suns, distant enough to be stars. Such a hypothesis, in that day and age, would have been about as likely as the existence today of robots masquerading as people. Yet you could test for the former. How do you test for the latter? I am trying to understand the BASIC underlying philosophy of scientific progress, and you people are saying "dude, just take a random sample and see if they're robots", as though that were a meaningful answer. How is it meaningful: I know with certainty 1 that if I "take a random sample and see if they're robots" the answer will be "0 of my sample was". But I don't have the chance to sample just anyone out of the world's 7b people. I can sample whoever is around me (geolocate my IP if you want)... going from this to estimating whether there are robots walking the earth seems to me to be a stretch at best. I hope I have now clarified the depth to which a real answer must answer. --188.29.154.125 (talk) 23:37, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

There is, in fact, one true scientific method: Hypothesis are proven by observed evidence. Usually that evidence is from controlled experimentation. The problem is in social science research (a field I've worked in) you can't conduct a controlled experiment. The best you could do in this case would be to survey a truly statistically random sample of the population. 98.209.39.71 (talk) 23:57, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I don't get why you call this the "social sciences". I would think this is an extremely hard scientific fact. Either there are "people" with normal human relationships but who are really robots/androids/etc, not flesh and blood borne of the womb of a human mother, or there are not. How do I determine this? "Survey some 'people'" cannot possibly work as a methodology - what can? --188.29.154.125 (talk) 00:45, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

One of the basic principles of the scientific method is that it is not possible to prove a universal -- only to disprove one. "No humans are robots" is a universal. Therefore it is not provable. Looie496 (talk) 00:48, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- One of the currently popular summaries of what is and is not science revolves around the concept of falsifiability. To be science, it is argued, something must be falsifiable. "There could be (at least hypothetically) a person (somewhere) who is actually a robot" is not falsifiable (there isn't any test or experiment one could do to disprove the statement), and as such would not be counted as a scientific hypothesis in that view. "No person in this particular room is a robot" is falsifiable (one can test every person in the room for being a robot), and would at least be considered for the status of a scientific hypothesis. Note, however, if you get nebulous/tricky on the definition of being a robot (e.g. "well, the robots I'm thinking of look and act exactly like humans, and any test you do on them couldn't tell them apart from humans"), then "No person in this particular room is a robot" can cease to be falsifiable (as there is no test you can do to disprove it), and thus ceases to be counted as a possible scientific hypothesis. -- 140.142.20.229 (talk) 01:18, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think that to scientifically test for specifically robots, you'd need a working theory on the kind of robots they are and the methods they're using to hide from humanity.

- Obviously, you wouldn't need that theory to just stumble across a robot during the course of some other investigation, but if you're specifically starting with the theory that some alleged humans are robots in disguise, and then attempting to prove or refute that theory, you're going to have to define it better first.

- However, if you're assuming typical androids with electronic and mechanical mechanisms inside, and no biological componants, and no interior componants that are disguised as biological componants, then it seems like the way to go would be to attempt to draw blood from from a random sampling of mankind, and do the usual statistical math to estimate the min/max percentages.

- You might also be able to do statistical analysis on published data. If you take it as given that a robot destroyed in a traffic accident would be discovered as a robot, and that no robots have ever been discovered in that manner, then you could do some number crunching to figure out the maximum percentage of alleged humans that could potentially be robots before it becomes statistically ridiculous that none have ever been discovered after a traffic accident. APL (talk) 10:31, 2 July 2011 (UTC)