Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2009 February 13

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < February 12 | << Jan | February | Mar >> | February 14 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

February 13

[edit]Post-It Note adhesive Thickness

[edit]I just got back from a trade show, and one of the bits 'o swag was a "brick" of Post-It Notes, about 2-3/4 inch (70cm) thick.

All the notes have the adhesive on one edge. It's a continuous strip of adhesive on each sheet, about 3/4 inch wide, and the paper is about 2-3/4 x 2-3/4 inch, making the brick almost a perfect cube.

I would have expected the thickness of the adhesive to be obvious along the adheded (is that a word?) edge. However, the cube looked flat. So I got out my Mitutoyo CD-6"P calipers, and took some measurements. 10 sheets measured .0415", making each sheet 4.15 mils thick. The thickness of the brick was 2.7815", meaning that (rounding off here) there were 670 sheets in the brick.

Now I admit that the caliper measurements aren't perfectly repeatable, since I can't calibrate the force I use use when making a measurement. But I was unable to detect any difference between the thickness of the adheded (there it is again) edge, and the plain edge.

If we assume that the thickness of the adhesive was a millionth of an inch, that would make a difference of .67 mils over the thickness of the brick, which would be just detectable using this crude instrument.

I find it hard to believe that such a thin coating is possible, but I hold the evidence in my hand. I checked the Wikipedia article and Googled around trying to find out the thickness of the adhesive layer with no luck. Any of y'all have an idea where I can get that information? Thanks. Bunthorne (talk) 00:03, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- oh my god do I envy the kind of time you seem to have!!! 82.120.236.246 (talk) 00:20, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Well, you know, I don't think this took him more than five minutes with the calipers. -- Captain Disdain (talk) 02:37, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- and writing the above? and rumination ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.120.236.246 (talk) 03:53, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- You're right, it was a downright Herculean effort. How did he find the time?! -- Captain Disdain (talk) 08:56, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- It helps to schedule some ruminatin' time every day. (Read, 'rite, ruminate!) —Tamfang (talk) 02:41, 21 February 2009 (UTC)

- Once you start looking at scales of a millionth of an inch, the surface of a piece of paper is anything but flat. --Carnildo (talk) 01:44, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Does the micro-weight of the sticky area vs non-sticky come into it? Julia Rossi (talk) 01:58, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Micro weight maybe not, but macro weight they flatten the block under while producing (cutting) it. You can buy this Postit type adhesive in a spray can. Other than glue or the sticky stuff on the back of Duct tape, this type of adhesive doesn't add much if any bulk. The material will try to "even out" when pressed and so the fibers sticking out of the non adhesive part will not be depressed as much by comparison as the part with the sticky layers. 76.97.245.5 (talk) 04:09, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Here's a side issue on this topic. The chemist at 3M who invented the Post-It adhesive was trying to develop a powerful new glue. When he came up with a weak adhesive, his cohorts laughed at him and made him the butt of jokes. However, he had the last laugh. – GlowWorm —Preceding unsigned comment added by 98.17.32.201 (talk) 18:17, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- It's interesting to note that the post-it 'brick' that I have has alternate sheets glued at alternate ends to form a 'zig zag' of sheets. I wonder whether they did that specifically to circumvent the theoretical difficulty that our OP mentions when (possibly) using less absorbant paper or something? SteveBaker (talk) 21:20, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- The alternating post-it brick is used for a post-it dispenser. If all the sheets are glued on the same side, when you pull one out the top, it will lift the whole brick, come loose, and then you'll have to hand-feed the next sheet through the slot on top. If they alternate, pulling one will lift the next sheet through the slot at the top before separating from it. -- kainaw™ 21:27, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- It's probable that the adhesive and paper are sufficiently compressible so that the "adheded" edge is of the same thickness as the uncompressed, paper-only parts of the block. As the OP mentions, "compression" force resulted in a slightly non-repeatable measurement by calipers. Though it's hard to imagine, the individual sheet of paper probably squeezes into a perfect little rectangular prism of fairly uniform thickness (height?), even though there is more material on the "adheded" edge. (Alternatively, there could be slightly thinner paper on the "adheded" side, but this would be really hard to manufacture).

- Now, to verify my original assumption, you could probably perform an experiment to slice the cube into only-paper and paper-plus-adhesive blocks. Measure the mass of these, and calculate the excess mass which must be due to the adhesive. I think that there will be a serious signal-to-noise problem, bordering on the un-measurable, but for the sake of science... we must try. Nimur (talk) 18:51, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- I'd love to try Nimur's idea, which borders on genius, but the only instrument I have to measure mass is a bathroom scale. I could probably weigh myself holding the subjects, but I'm afraid the closest reliable reading is +/- 2 pounds, so I'd have to get either a somewhat better scale, or a massive number of bricks. Thanks for the ideas. Bunthorne (talk) 05:24, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- It's not the language desk, but I believe the correct word is adhered. My money is on the manufacturing process. Compressing the sticky edge with an industrial machine in a way that can't be matched by your measuring caliper. -- MacAddct1984 (talk • contribs) 21:12, 17 February 2009 (UTC)

- If counting thru a 2 inch brick of post-it notes takes time on one's hands, look at some of the post-it animations on www.eepybird.com and imagine what that must have taken. 207.241.239.70 (talk) 08:14, 18 February 2009 (UTC)

Sorry if it sounds like I'm nitpicking, but 2 3/4 inches does NOT equal 70 cm . . . maybe 70 mm??

Tesla, Edison, Einstein and Asperger syndrome.

[edit]Just out of curiosity, did Tesla, Edison and Einstein all had Asperger syndrome? I read that somewhere and I was wondering if it's true. Thanks in advance. ― Ann ( user | talk ) 00:41, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Well, Hans Asperger first described what has since become known as Asperger syndrome in 1944, a year after Tesla died and 13 years after Edison died. Einstein died 11 years after that first description, but still well before the term "Asperger syndrome" was first popularised in 1981, and even longer before it become a common diagnosis. So, anyone saying any of them had Asperger syndrome is making, at best, an educated guess based on historical accounts. To get any kind of reliable diagnosis requires an intentional assessment of a wide variety of qualities. --Tango (talk) 00:52, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I've read a couple of biographies of Einstein and he does have a lot of the attributes of an Asperger sufferer. Comparing his story to the criteria in DSM IV, he pretty clearly could be diagnosed that way on the basis of the information in his bio's. I don't know enough about Edison or Tesla. It wouldn't surprise me if Tesla was and Edison wasn't...but I really don't have enough information. SteveBaker (talk) 03:55, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- It's tough to apply diagnoses backwards in time—heck, it's not even easy to apply them to real, living people! Einstein's a tough nut to crack in particular because everyone sees him as what they want to see him as... --98.217.14.211 (talk) 16:52, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I agree. But from the DSM IV description, I think Einstein can easily be shown to have had:

- A2) Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level.

- A3) Lack of social or emotional reciprocity.

- B1) Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus.

- C) Significant impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning.

- D) No delay in aquisition of language as a child.

- E) No delay in cognitive development.

- F) Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorder or Schizophrenia NOT present.

- A2—the man had plenty of friends, lovers, etc., throughout his life. A3—the man was a life-long activist for the suffering, wrote passionately on the subject, got denounced by the Nazis and a 1,000 page FBI file for his troubles. B1—how exactly where his patterns of interest restricted? Patent examiner, theoretical physicist, social activist, violinist, writer, lecturer, etc.? C—what was so impaired? Are we just using the "Einstein was a weirdo" stereotype here, or are we basing this on his actual life and interactions? D,E,F—a lack of something abnormal seems hardly relevant here?

- As with anybody as "iconic" as Einstein there is an elaborate mythology and stereotypes of his behavior that have percolated throughout culture. The idea that Einstein had his "head in the clouds" and thought of nothing but physics is plainly false (it is easy enough to see if one reads his collected essays—the man had tons of interests, was extremely cultured, was very "down to earth" on a wide variety of things).

- My point in being contrarian here is not to make strong statements about Einstein, but to point out that each of those criteria are extremely subjective. Even in a living, breathing, non-famous person they can be quite ambiguous in everything but the outlier, extreme cases. With a historical figure around which an expansive mythology has been built—one that is demonstrably not even close to being accurate, like the one of Einstein as being a spaced out mystic old grandpa—it seems rather impossible to me to make a retrospective analyses unless of course they are one of the outlier cases (and Einstein doesn't seem to be one of those). For example, the fact that Einstein was a subversive civil rights activist and an unapologetic socialist is something that has long been underemphasized, as it for decades made people politically uncomfortable (even today, while his civil rights work is now much more paid attention to, his socialism is downplayed, though it is clear it was important to him for most of his life). He's not as simple as the caricature of him makes out. --98.217.14.211 (talk) 19:23, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Where do people get this idea that Einstein had Asperger's? Never mind a detailed look through a list of symptoms, who would ever come up with this idea in the first place? It seems to be based on nothing more than the idea that smart people must be "different from the rest of us". People seem shocked that a smart person might go to clubs or be a surfer or womanize. The perception of intelligence as a kind of mental abnormality is a threat to the future of the human race. We should be fighting these nonsense diagnoses, not entertaining them. -- BenRG (talk) 13:56, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. Asperger's is a very fashionable diagnosis at the moment, and it's common for people (not doctors, so much, they know a little better) to diagnose every smart person that has difficulty making friends as having it. I'm a smart person that has difficulty making friends, I do not have Asperger's (I was tested for it). I put my difficulty making friends down to two things, difficulty finding people I have something in common with (that gotten easier as I've moved up through education, there are plenty of smart people around once you get to Uni), and the fact that I was bullied in school because of my intelligence and as a result I tend to be quite closed off emotionally (a couple of pints helps with that!). I expect those reasons apply to a large number of smart people. (I should make it clear, I do have plenty of friends, it's just difficult to form that initial bond.) --Tango (talk) 14:20, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- The initial bond thing is key here. If someone struggles to make friends, but once made, can chat away easily with them, then the person probably has trust issues (awaits big pharma companies to start pushing oxytocin reuptake inhibitors or the like). If the person just cannot empathise with people and doesn't chat to those they know well, then it is more likely Asperger's. --Mark PEA (talk) 12:40, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. Asperger's is a very fashionable diagnosis at the moment, and it's common for people (not doctors, so much, they know a little better) to diagnose every smart person that has difficulty making friends as having it. I'm a smart person that has difficulty making friends, I do not have Asperger's (I was tested for it). I put my difficulty making friends down to two things, difficulty finding people I have something in common with (that gotten easier as I've moved up through education, there are plenty of smart people around once you get to Uni), and the fact that I was bullied in school because of my intelligence and as a result I tend to be quite closed off emotionally (a couple of pints helps with that!). I expect those reasons apply to a large number of smart people. (I should make it clear, I do have plenty of friends, it's just difficult to form that initial bond.) --Tango (talk) 14:20, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Where do people get this idea that Einstein had Asperger's? Never mind a detailed look through a list of symptoms, who would ever come up with this idea in the first place? It seems to be based on nothing more than the idea that smart people must be "different from the rest of us". People seem shocked that a smart person might go to clubs or be a surfer or womanize. The perception of intelligence as a kind of mental abnormality is a threat to the future of the human race. We should be fighting these nonsense diagnoses, not entertaining them. -- BenRG (talk) 13:56, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- I have never seen strong indications that Thomas Edison had Asperger's syndrome. He was a personable and charismatic leader of a research group, able to impress financiers, writers and the general public. He always had a group of close friends, contra-indicating Asperger's. He could be quite manipulative, indicating an understanding of the inner thoughts of supporters and competitors. He liked to experiment as a child with chemicals, but was not the overly verbal "little professor." An Aspie would not have been able to set up a business selling treats and self-published newspapers on a train as did the young Edison. "The wizard who spat on the floor" was one characterization.He was a deaf gadgeteer and his one great emphasis in life was inventing for the sake of inventing. Tesla, on the other hand seemed obsessive-compulsive and psychotic/delusional more than Aspie. Einstein was pretty odd in his lack of interpersonal loyalty towards spouse or offspring,and had some oddities in his childhood, but I have no strong opinion as to whether he had Asperger's. It does seem a bit grasping for Aspies or their family members to try and claim historical figures as fellow non-neurotypicals. Edison (talk) 02:08, 17 February 2009 (UTC)

comb attracting little pieces of paper

[edit]Classic physics example: A comb that's been rubbed can attract little pieces of paper. The explanation I've read is that the comb becomes charged, and it causes the neutral paper's atoms to be polarized. The positive ends of the atoms in the paper are attracted to the negatively charged comb. But that doesn't seem to make sense, because the negative ends of the atoms would equally be repelled by the paper. Since there are equal #s of negative and positive on the paper, shouldn't there be zero movement (no attraction/repulsion)? Also, the paper sometimes are repelled? Why? Thanks in advance. 128.163.224.222 (talk) 03:38, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I can't really recommend our pages Static electricity and Triboelectric effect. The simple Wikipedua version is shorter, but I can't say I find it more enlightening [1]. Nevertheless you might find them useful. 76.97.245.5 (talk) 04:25, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

Similarly to the recent question about Saturn's gravity, the answer lies in the fact that the electric charge is only one of the factors governing the strength of the electic force. The other factor is the distance. As the negatively charged comb atracts the positive charges in the paper and repells the negative ones, those charges separate and the positive charges come closer to the comb. That way the atractive force becomes stronger than the repulsive force and the paper ends up being atracted. Dauto (talk) 05:52, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I think something like that would be good on our pages. Would s.o. have the time to write it up? 76.97.245.5 (talk) 08:29, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- That doesn't make sense to me. If the comb attracts the positives, it should repel the negatives an equal amount for a net of zero. I thought that the presence of the electrons on the comb (or absence, I don't know which) would make it have a net charge with respect to, well, the rest of the universe, basically. Let's say the comb has excess electrons (it doesn't matter); the paper bits would have a positive charge with respect to the comb and would be attracted. A pile of lead shot would be equally attracted to the comb but would be too heavy to be lifted or even moved by the feeble forces involved. --Milkbreath (talk) 13:21, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- If the comb has excess electrons, they will repel the electrons (it's the electrons that are mobile) in each bit of paper. So the electron cloud around each atomic nucleus in the paper is very slightly displaced - it is no longer centred on the nucleus. The net effect over the whole piece of paper is that there is a slight deficiency of electrons nearest the comb and a slight excess furthest away. Force dimishes as the square of the distance, so the attraction of the positive end of the dipole is greater than the repulsion of the negative end. Philip Trueman (talk) 13:31, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- If I remember correctly, it's called electrostatic induction. (Just giving a name to Philip's explanation) --Bennybp (talk) 13:57, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Further proof that I'm seriously stupid. If the comb is pushing the electrons in the paper away, that force is pushing the paper away, or those electrons would go right back where they were. The reason that that force doesn't make the paper move away is that the now-exposed positive charges attract the comb, for a net force of zero. I must be thick as a brick. --Milkbreath (talk) 14:31, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- The comb will now actually attract the paper, since now the positive charge is closer to the comb, and the negative charge is farther away (Coulomb's Law). I've never seen it done with a comb and paper, but balloons (one charged will actually attract a neutral one). --Bennybp (talk) 16:22, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

Paper is (very) slightly conductive. When the comb becomes charged, the difference in charge between it and the bit of paper causes the paper to be attracted to the comb. When the charge on the paper becomes equal to the charge on the comb, it is strongly repelled. Try this with a bit od cereal(slightly conductive) suspended from a silk or polyester thread(insulator), and a rubber (insulator) comb or PVC pipe rubbed with wool or silk or whatever. The bit of cereal will be strongly attracted to the comb until it gains charge, then strongly repelled. It is not necessarily a matter of polarization. It is a matter of different charges attracting, and transfer of charge. For a polarization demo, bring the charged comb near, but not touching, an insulated piece of metal. The far end of the metal object will then repel a Cheerio charged from the same comb. This is just stuff Steven Gray discovered in the early 18th century. Electroscopes work nicely by induction.Edison (talk) 02:17, 17 February 2009 (UTC)

Syndrome or Disorder?

[edit]In order to respond to our previous question about Asperger syndrome and Einstein - I looked up the precise symptoms in the 'DSM IV' (which is the 'bible' of psychiatric diagnosis).

Why is it that DSM IV describes Asperger's as "Asperger's Disorder" and not "Asperger's Syndrome" as everyone else seems to do? Is there some important difference between a "Disorder" and a "Syndrome" in psych terminology?

SteveBaker (talk) 04:01, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- In technical discussions, a "disorder" or "disease" refers to the underlying condition or malfunction, while a "syndrome" refers to a collection of co-occurring symptoms or signs. A syndrome need not have unique cause, as the same constellation of symptoms might be caused in multiple different ways. In practice, the distinction may be abused or ignored, especially since many syndromes actually do only point to one unique cause. Dragons flight (talk) 04:16, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- So DSM is saying that Asperger's has a single underlying cause? Interesting. SteveBaker (talk) 04:50, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Not quite, it's thought to have seveal underlying causes. We're just not entirely sure what they are yet, most likely genetics. —Cyclonenim (talk · contribs · email) 07:39, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Well, that's what I thought - so back to the original question: Why 'disorder' and not 'syndrome'? In fact - a quick skim of the DSM IV index suggests that they never call anything a 'syndrome'. On the other hand we have 'AIDS' which is a syndrome (that's what the 'S' stands for). SteveBaker (talk) 08:05, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I was doing a project for a client that had me read up on a medical topic. I then started work on a related wikipedia page and after a while was happy if I had a term where there were not at least 2 different versions describing the same thing with factions warring whose term was the better one. (First prize went to 5 varieties for one item.) Mental disorder and Classification of mental disorders say there are two accepted systems ICD and DSM. So maybe they are using different terms to reflect different views. Or they're just defending their turf. 76.97.245.5 (talk) 08:47, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Well, that's what I thought - so back to the original question: Why 'disorder' and not 'syndrome'? In fact - a quick skim of the DSM IV index suggests that they never call anything a 'syndrome'. On the other hand we have 'AIDS' which is a syndrome (that's what the 'S' stands for). SteveBaker (talk) 08:05, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Not quite, it's thought to have seveal underlying causes. We're just not entirely sure what they are yet, most likely genetics. —Cyclonenim (talk · contribs · email) 07:39, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- So DSM is saying that Asperger's has a single underlying cause? Interesting. SteveBaker (talk) 04:50, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- There's a desire in the community at large to "de-perjorify" language in an imprecise way. The word "disorder" implies a negative thing, that there is a normal (i.e. order) way to be, and that if you have a condition, that condition represents a "dis"-order, i.e. not normal, i.e. you are broken. Over time, there has been a trend in society to change the terms to remove distinctions that imply "brokenness" or "less than normalcy" for all sorts of conditions. Consider the spectrum of terms: mentally retarded-slow-mentally handicapped-mentally challenged-mentally different-exceptional. Over the past 30 years or so, these terms have been used to describe the exact same set of conditions in an individual. Look at the early end of the spectrum compared to the modern term, "exceptional". Exceptional even sounds like its a benefit. Does little Joey have a learning disability? No, he's "exceptional". Same deal with disorder vs. syndrome. A disorder implies that something is broken that requires modification in order to work. A syndrome merely sounds like a set of differences that requires no intervention. We need to fix a disorder. You need to learn to live with a syndrome. The medical professionals who wrote the DSM IV sound like they aren't necessarily caving to political pressures to use imprecise or cuddly language. These are real problems, and require real interventions in order to help people cope with them. Asperger's is not like being left handed; it's not a neutral condition with regards to how people interact socially in the world, and it requires serious minded people who are willing to approach it in a way that helps people who have it integrate in the world in a meaningful way. Changing its name does not change the need to deal with it properly. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 17:24, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed no! I'd be violently opposed to anyone trying to 'fix' my Asperger's - for me, the benefits outweigh the losses. Not all aspies feel that way though. I wouldn't object to 'disorder' though - there is definitely something wrong with my brain - it's just that the consequences of that 'wrongness' are a mixed bag of benefits and down-sides. What I would wish for is MUCH earlier detection - and proper training to help aspies know what their limitations are and how to work around them. I didn't find out until maybe 10 years ago - and knowing what I know now, I just cringe at some of the things I totally screwed up as a kid and young adult. SteveBaker (talk) 17:56, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Is there anybody without a 'disorder' at that rate? Just because a greater percentage of people do a thing doesn't mean it is the better way. For instance it is quite normal to get in a huff when criticized and ignore any practical lessons that there might be. It is quite normal to follow a leader and do what they do even if it is wrong and bad. Yes normal is a whole mixed bag of contrary ways of doing things, social anthropology may be a bit unscientific but appealing to the behaviour of bunches of ape men in caves seems about the best explanation. I wonder though what types of people the future belongs to. Dmcq (talk) 10:06, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

asexual reproduction

[edit]is it possible (for women) to reproduce asexually using the power of the mind alone? If so, are there any documented cases? If not, what physical constraints in the human body would prevent this effect? Thank you. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.120.236.246 (talk) 05:34, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Short answer: NO. A woman's body cannot produce the sperm necessary to fertilize one of her eggs in order to create a diploid cell. Other dipoid cells of the woman's body do not have the right genes activated in order to start a new embrio. Dauto (talk) 05:58, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Not in humans (although I'm not sure if it's technically impossible) and definitely not related to the power of the mind, but see parthenogenesis. Zain Ebrahim (talk) 09:07, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Also see the section Wikipedia:Reference_desk/Science#Same-sex_gametes_combining_to_form_a_zygote.3F. Mammals take two to tango. Even those genetically modifed mice that let you make a viable embryo out of two eggs doesn't make asexual mammals possible. Someguy1221 (talk) 09:18, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

Fingerprints

[edit]i always had doubts about this ..is it an absolute truth that finger prints are unique for each one , isnt been recoreded even for once that two indivisiuals has the same finger print , and when was the first time this finger print thing was mintioned ..??????? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Mjaafreh2008 (talk • contribs) 11:20, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Have you read Fingerprint#Validity_of_fingerprinting_for_identification? 130.88.151.87 (talk) 11:31, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- It depends on what level of accuracy you look at. Have there ever been two fingerprints from different people which were exactly alike ? Probably not. Have there been two different prints which were close enough to be mistakenly taken to be the same print ? Absolutely. This is especially true if fingerprints are smudged or partial, as they frequently are at crime scenes.

- Another factor that comes into play is use of fingerprint databases. Let's say that a match can be found with only a 1 in a million rate of misidentification of the wrong person. If fingerprints are used to compare a crime scene print with a suspect seen leaving the premises around the time of the murder, then it's very unlikely the print will be found to match if it doesn't. So, that's a good usage. But now let's imagine that nobody was seen leaving the scene, and instead they run the print against a database that contains millions of fingerprints. With that 1 in a million failure rate, you'd expect one or more to match, just based on chance. Arresting such a person, based solely on their fingerprint, would not serve justice. Investigating people further who match might make sense, though. If one of them was an acquaintance of the murder victim, and has a record of performing similar murders, then an arrest would make sense. StuRat (talk) 15:52, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

WILL ... mabey op should look in the link he listed beforehttp://www.metacafe.com/watch/98111/miracles_of_the_quran_12/ i dont think this is a coincidence too , dont you think —Preceding unsigned comment added by 94.249.98.74 (talk) 19:36, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- The article cited above on validity and reliability of the method noted that the FBI incorrectly said there was a match between the prints of an innocent man (as later determined) and prints left by a terrorist bomber. The validation of the methodology has apparently been mostly by handwaving assertions rather than scientific and objective testing. Edison (talk) 01:00, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Note that many of the failings of fingerprints can also apply to DNA testing. That is, while both prints and DNA are supposedly always unique (although, in the case of identical twin DNA, you'd need to look in great detail to find mutations, etc.), they can both still fail to identify, with either false positives or negatives, for similar reasons:

- 1) Poor quality prints or degraded DNA can both result in people declaring a match, when they really don't have enough data to say with any certainty.

- 2) Both are subject to simple human error, like accidentally submitting the same sample as if were both prints/DNA samples, resulting in a false match.

- 3) Both are subject to the expert lying on the stand about there being a match, due to bribes, pressure from the prosecution, threats from the defense, etc. Prints aren't quite as bad, in this respect, though, as jurors are more able to judge for themselves whether a match exists (provided they are actually shown the correct samples). StuRat (talk) 14:46, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

Snowflake symmetry

[edit]Why are snowflakes symmetrical? How does one leg know to become exactly like the others? --Milkbreath (talk) 12:04, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I think the answer (i.e. I read it somewhere once - but here's a link) is that in general they aren't: it's just that the pretty symmetrical ones are those whose photos get into the books. AndrewWTaylor (talk) 13:02, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. Our article on snow says "The most common snow particles are visibly irregular, although near-perfect snowflakes may be more common in pictures because they are more visually appealing". Gandalf61 (talk) 13:18, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I've looked at a lot of snowflakes over the course of a life lived mostly at 40 North. When you do get individual snowflakes, they are quite regular. I don't know what those articles are talking about. But, leaving that aside for the moment, let me rephrase the question: In the not uncommon snowflake that in gross structure is radially symmetrical, what forces are at work in creating the symmetry? How can one leg know what the others are doing, so to speak? --Milkbreath (talk) 13:28, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- See http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=why-are-snowflakes-symmet Cheers.--Fuhghettaboutit (talk) 13:42, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Good link. So, nobody knows. I can live with that. --Milkbreath (talk) 14:37, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I don't think there is any mystery here. The six branches of the snow flake presumably grow radially outwards at the same rate, and the length and breadth of side branches or plates depends on the temperature and humidity that the snowflake is experiencing at a given point in time, so it is not surprising if all branches show similar sequences and patterns of side branches. Observer bias then makes us focus on the symmetries and ignore the imperfections. If you look closely at the photographs here or here or even in the iconic Wilson Bentley photographs, you see that the symmetry is far from perfect. Gandalf61 (talk) 15:20, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I think we know. The core ice crystal is hexagonal - as the crystal is swirled around inside the cloud, it accretes more ice until it becomes too heavy to stay inside the cloud and then falls to earth. In general, whatever humidity/temperature/pressure changes happen to one face of the crystal happen identically to the other five faces - so however one side grows, the other sides tend to grow the exact same way. What makes them slightly asymmetrical is that the conditions may not be PRECISELY the same on all six arms and also, sometimes they are damaged by collisions with other snowflakes. SteveBaker (talk) 15:30, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- (ECx2) They gave a good explanation, the same one I thought of:

- 1) Different temp/humidity combos result in many different types of branching.

- 2) Since the conditions are likely to be identical on all sides of the flake, the branching is likely to be the same on all sides.

- 3) When temp or humidity do change, during snowflake formation, the type of branching changes on all sides of the flake. The result is a complex, yet symmetrical, formation.

- 4) So, then why are so many not symmetrical ? I suspect that collisions are the main culprit, allowing flakes to break or stick together.

- It also seems to me that this is part of a larger question: Why do crystals, under ideal conditions, tend to form symmetrical shapes ? The explanation would be similar to that for snowflakes. StuRat (talk) 15:33, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Why are snowflakes flat? Most crystals have substantial amounts of material in three dimensions. Does the thickness vary in different snowflakes? Are there bumps or other extrusions on the flatness that vary in size and placement in different snowflakes? If there are bumps, do they form a pattern, perhaps hexagonal? Has anyone photographed, or even examined, snow flakes viewed on edge? – GlowWorm —Preceding unsigned comment added by 98.17.32.201 (talk) 17:08, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- One of the links Gandalf61 posted lists a variety of snowflake types, many of which are far from flat. Depending on the temperature the snowflake forms at, it may grow primarily along the c-axis ("vertical"), and come out as something like a thin needle; or it may grow primarily along the a-axes, and come out flat. Take a look at the morphology diagram here. Also, snowflakes generally don't form at constant humidity and temperature — so for instance if one starts forming at a temperature that drives c-axis growth, then (because of a temperature change) switches to a-axis growth, you'll get something like a capped column. -- Speaker to Lampposts (talk) 08:07, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- I missed that link. I'll order a couple of those books. – GlowWorm. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 98.17.32.201 (talk) 10:16, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

Was Banting really the first to discover insulin?

[edit]People in Romania believe otherwise !They say it was Palescu!(Ramanathan) —Preceding unsigned comment added by 212.247.70.129 (talk) 13:22, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

And was it Best or MacLeod who should be credited as his partner in discovery?(Ramanathan) —Preceding unsigned comment added by 212.247.70.129 (talk) 13:24, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Our article insulin says that Nicolae Paulescu was the first to isolate insulin, both those articles, and the references cited in them, should be of interest to you. DuncanHill (talk) 18:06, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

Freemartin

[edit]What does the term freemartin mean relating tocattle prodution and what causes this condition ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 66.244.104.243 (talk) 16:26, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Have you found our article freemartin yet? DuncanHill (talk) 18:03, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

Faster-than-light communication idea

[edit]I believe physicists that nothing can travel faster than light, c, at 300,000 m/sec. But what nothing actually had to move for something meaningful to be transmitted superluminally?

Here's my idea: (see picture here) A giant rigid cylinder made of super-strong material extends between two points in space that are one light-year apart, A and B. (Disregard the engineering infeasibility, gravitational influence of stars, galaxies, dark matter, etc.) At each end of the light-year long cylinder is a wheel with a peg to turn it. Initially, the peg at A is exactly at A and the peg at B is exactly at B. If I turn the peg from A to A', how long does it take for B to go to B'?

I see two possible outcomes:

1. Holy cow it's the answer to superluminal communication! (unlikely)

2. The rotation from the A end of the cylinder will "travel" across to point B over time, probably taking a little more than a year.

What do you folks think? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Marskid2 (talk • contribs) 16:57, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- (EC with coneslayer. I will assume his answer was similar to this). In any real material (i.e., one made of atoms which obey the laws of physics in this known universe) there is no such thing as a "rigid" cylinder. Rigid is only relative, and at the sizes you describe, there will be some deformation along the rod. When you turn A towards A', the rod in the middle begins to twist torsionally. Think if you had a piece of clay in your hands, and held one end steady while the other end you twisted. The rod will do the same thing. Now, over time, the "twist" will travel down the rod towards B, however this obviously will occur at some rate slower than the speed of light, the movement of A towards A' will not occur at the B side until the "twist" arives there. Thus, the laws of the universe are safe from giant imaginary rods. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 17:12, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Ah that makes sense now. I definitely didn't realize how big of an assumption "rigid" was. Thanks for the quick answers! =) marskid2 (talk) 17:15, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- To elaborate a bit further: Your rod's stiffness is caused by chemical bonds, i.e. electromagnetic forces. These are communicated via photons. So any disturbance of the rod can at most travel down it at the speed of photons (i.e. the speed of light). --Stephan Schulz (talk) 17:26, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Is anyone collecting these? In the past few years, I've seen suggestions that we use long ropes, metal bars, crystal rods, long nano-tubes... etc. I'm waiting for "What if we used a really long fish?" -- kainaw™ 19:07, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- We already know the whole idea is fishy, these are just specific variations. DMacks (talk) 19:21, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Here [2] is a fish-powered perpetual motion machine. You have to scroll through dozens and dozens of other ideas but eventually:

- "If we made a fishing rod with a tiny motor-battery combo, and it would cast out til it caught a fish, and the fish when caught was pulling against the motor til it ran backwards and recharged the battery for the next cast, we would have made another perpetual activity er motion. It would, of course, have to sense the battery charged up & generate a lure-release."

- (You can tell it's a crackpot site because it's using LOTS of color/italics/underlining)

- SteveBaker (talk) 21:06, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- To give him credit I think it lost something in translation from the original schizophrenia. --98.217.14.211 (talk) 04:53, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Here [2] is a fish-powered perpetual motion machine. You have to scroll through dozens and dozens of other ideas but eventually:

- I had a tube full of marbles yesterday. --Carnildo (talk) 00:51, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- We already know the whole idea is fishy, these are just specific variations. DMacks (talk) 19:21, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Is anyone collecting these? In the past few years, I've seen suggestions that we use long ropes, metal bars, crystal rods, long nano-tubes... etc. I'm waiting for "What if we used a really long fish?" -- kainaw™ 19:07, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I thought I had one also, but everyone says I lost mine years ago... DMacks (talk) 01:52, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Just for the record, the speed of light is about 1000 times faster than what you said. :) -- Aeluwas (talk) 16:55, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. I expect the OP meant km/s. --Tango (talk) 17:38, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Just to answer Marskid2s original scenario, the torque on the cylinder will travel along its length at the rate of shear waves in the material, which is a little less than the rate of (longitudinal) sound waves. Assuming the cylinder is made of steel, for which the speed of sound is about 5930 m/s, the twist will travel from one end of the light-year long cylinder to the other in a little more than 50,600 years. --ChetvornoTALK 07:10, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. I expect the OP meant km/s. --Tango (talk) 17:38, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

PROPELLER ENGINE VS JET ENGINE AT HIGHER ALTITUDE

[edit]IS THERE MATHEMATICAL PROVE FOR DECREASE IN PROPELLER ENGINE EFFICIENCY AT HIGHER ALTITUDE IN COMPARISION TO JET ENGINE —Preceding unsigned comment added by 114.31.179.11 (talk) 18:34, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- First, typing in all caps is the equivalent of screaming at everyone. Would you walk into a library's reference desk and immediately start screaming at the poor woman behind the counter?

- Second, check Newton's laws of motion. How does a propeller work? It forces air in one direction, causing the propeller to move in the opposite direction. If there is less air, there is less are to move. How does a jet engine work? Fuel is placed into a confined area. Combustion causes thrust to escape. The thrust is channelled in a specific direction, causing the engine to go in the opposite direction. The air is not used, fuel combustion is. If you take oxygen with you, you can continue using a jet engine at any altitude you like, but a propeller engine will fail at rather low altitudes for aircraft flight. -- kainaw™ 19:04, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

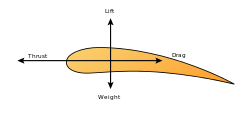

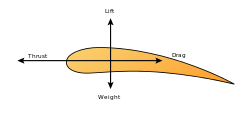

Forces on an aerofoil - Well, that's not the full story, as the illustration of a wingform shows. Rotate that illustration 90 deg anticlockwise and you get a propellor blade, and the lift becomes the thrust. Also, your explanation of how a jet engine works is a bit off too. The thrust created in a jet engine is not just the escaping gases rushing out the back. Remember when you were a kid you blew up a balloon, then let it go and it flew crazily around the room? That same balloon will behave in exactly the same way if you let it go in a vacuum where the escaping air has absolutely nothing to push against. The pressure inside the balloon creates the thrust, not the air being expended, and the balloon moves away from the point of low pressure (where the air is escaping). If that didn't happen we couldn't steer/guide vehicles in outer space which is a vacuum.

- I don't think it is necessary to be quite so sniffy with people who type in all caps. Its not really the same as shouting in a library and their typing skills may not be as good as yours. SpinningSpark

- Most people mean by jet engine a turbofan engine as used on commercial aircraft. These engines require an air intake for the compressor and have a definite altitude limit. Although technically the term includes rockets which carry their own oxidizer I think the OP probably meant turbofan. You can find a comparison of the altitude records for both types of aircraft at Flight altitude record. Both types will lose efficiency as air density decreases but I don't think you are going to find a simple formula to compare them as it depends on many aircraft design factors. SpinningSpark 22:47, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

2009 satellite collision relative velocities

[edit]Hi guys. I'm trying to add some detail to 2009 satellite collision and I'm looking for reliable sources on the relative velocities of these satellites. I've found a few sites [3] but these are "amateur" estimates fraught with speculation. Has anyone got any good sources for the relative velocity of the strike? Nimur (talk) 19:47, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- This forum seems to use more rigorous math to ge 3.4 km/s. Still hardly a reliable source. Nimur (talk) 19:57, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I do not understand why the relative velocity would be so high (26,000 mph per the article, or een the 3.4 km/sec estimate above). If they were in circular orbits at the same height, and in the same orientation, the relative velocity should be zero. In a given orbit, satellites could be placed at the same height and orientation, spaced around the earth. Eccentricity of orbit would introduce some relative velocity. Orbits at different orientation would introduce additional velocity. Why would the launching countries place satellites in conflict orbits, where high speed collisions are likely? If a satellite is defunct, shouldn't the launching country be responsible for controlled de-orbiting (by retrorocket on board or by their or others' robotic deorbiting mission? Isn't there some coordination of orbits, to avoid the proliferation of long lasting space junk in valuable orbits, like airliners do not fly around willy-nilly ? Is there the likelihood of this debris hitting other satellites and causing even more hazardous space junk? These orbits are high enough that the junk might not reenter for a very long time. Edison (talk) 00:56, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- All of these are very valid points. When I first heard of the collision, I presumed the satellites must have been in the same orbit, with a slight separation of distance; and I assumed that the relative velocity must have been a "slow drift" on the order of meters per second that never got noticed until the two collided. However, this diagram[unreliable source?] seems to show that the two orbits were quite different ("so they cross paths at a 12 degree angle"[unreliable source?] of orbital inclination). (The map doesn't look like 12 degrees to me, but I'm not so sure the math was done right). As you say, how could this conflict of orbits have been overlooked when deciding the orbit for the launch planning for the Iridium satellite? Nimur (talk) 04:37, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- The orbits of spacecraft are affected by a multitude of factors which are very difficult to model. The satellites aren't traveling in perfect circles, the orbits change due to the effect of maneuvers, solar radiation pressure, atmospheric drag, effects of a non-spherical earth, third body effects from the moon and sun, etc. This means that orbits cannot be predicted with a high level of accuracy for long periods of time, and certainly not 12 years. Simply put, the two orbits didn't intersect when Iridium 33 was launched (in 1997), and it's likely no orbit could be chosen such that it doesn't intersect with some known object. Orbits are chosen to meet a large number of requirements, and like everything in engineering there is a trade involved. An orbit with very low risk of collision could be chosen at the expense of other requirements, or a higher risk orbit could be used and other requirements met.

- All of these are very valid points. When I first heard of the collision, I presumed the satellites must have been in the same orbit, with a slight separation of distance; and I assumed that the relative velocity must have been a "slow drift" on the order of meters per second that never got noticed until the two collided. However, this diagram[unreliable source?] seems to show that the two orbits were quite different ("so they cross paths at a 12 degree angle"[unreliable source?] of orbital inclination). (The map doesn't look like 12 degrees to me, but I'm not so sure the math was done right). As you say, how could this conflict of orbits have been overlooked when deciding the orbit for the launch planning for the Iridium satellite? Nimur (talk) 04:37, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- I do not understand why the relative velocity would be so high (26,000 mph per the article, or een the 3.4 km/sec estimate above). If they were in circular orbits at the same height, and in the same orientation, the relative velocity should be zero. In a given orbit, satellites could be placed at the same height and orientation, spaced around the earth. Eccentricity of orbit would introduce some relative velocity. Orbits at different orientation would introduce additional velocity. Why would the launching countries place satellites in conflict orbits, where high speed collisions are likely? If a satellite is defunct, shouldn't the launching country be responsible for controlled de-orbiting (by retrorocket on board or by their or others' robotic deorbiting mission? Isn't there some coordination of orbits, to avoid the proliferation of long lasting space junk in valuable orbits, like airliners do not fly around willy-nilly ? Is there the likelihood of this debris hitting other satellites and causing even more hazardous space junk? These orbits are high enough that the junk might not reenter for a very long time. Edison (talk) 00:56, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- It is difficult to predict when a conjunction will occur, and even then it is still probabilistic (a 1 in 25 chance of collision, for example). According to Space Debris, there are around 13,000 cataloged objects in orbit, and collision with almost any of them would be at high relative velocity, and thus catastrophic. To foresee any possible collision, conjunction analysis must be performed for every object which passes through the same altitude as Iridium 33 (or any other object you're interested in protecting), and there are probably thousands in this subset. Since the orbit of any object cannot be reliably predicted for a long period of time, this analysis has to be performed often, which is computationally intensive. When you run the analysis, all you get is probability; it isn't yes or no.

- Suppose there is a conjunction with some probability of collision (1 in 25, for example). Do you maneuver to avoid the debris? A maneuver has costs, both in consumables (fuel) and potentially downtime for the satellite (a maneuver might require pointing antennas away from their targets, or some other interruption to service). The line has to be drawn somewhere, and perhaps they chose wrong.

- Predicting events like this isn't cut and dried. It is a tradeoff between the risk and the cost of mitigating that risk. Perhaps Iridium didn't find it worthwhile to go through all of this, and mitigated the risk in other ways (on-orbit spare satellites). Perhaps their analysis was insufficient, or perhaps they chose to take their chances and the dice came up snake eyes.

- Of course there was little Russian Space Forces could have done since Kosmos-2251 was not functioning at the time. A spacecraft can stop functioning for many reasons, either predictably or unpredictably. Thus it is not always possible to deorbit a non-functioning satellite since it may stop working without warning. To foresee a collision is difficult, as illustrated above, and it's unlikely they would undergo all of the required analysis for a non-functioning spacecraft.

- As for the original poster's question, here is a picture showing the orbits of the two spacecraft. Unfortunately I can't find a good source on the relative velocity. My back-of-the-envelope number is about 10,600 m/s, or about 24,000 mph. To arrive at this I assumed two circular orbits at 776 km altitude, which gives an orbital velocity of about 7,500 m/s. The picture shows approximately 90 degrees between the two velocity vectors, making the relative velocity around 10,600 m/s. anonymous6494 07:08, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Wow - at those speeds, the odds of a collision with 90 degree orbital inclination is astoundingly small. The circumpherence of those orbits is around 40 million meters - if the spacecraft are (say) 10 meters long - then the odds of them colliding - even if their orbits do intersect is about 8 million to one against per orbit. At 8,000 m/s orbital speeds - each orbit takes a couple of hours - so you'd expect a collision like this about once every 400 to 500 years - even if they were both at the exact same altitude! SteveBaker (talk) 23:56, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- This is exactly what I was thinking, with similar back-of-envelope probability calculation. That's why I assumed the satellites were in an almost identical orbit, with much slower relative velocity - hence my original question. Of course, the slower the relative velocity, the more time would have been available to all parties to notice an impending collision and possibly avert it. But, the more I dig in to the actual orbits, I find a lot of different orbit diagrams and a wide variety of parameters described. Hopefully a post-incident press release will come out in a while with some more reliable numbers. Nimur (talk) 14:35, 16 February 2009 (UTC)

- Well, you might expect a collision between these two specific spacecraft to take place after 400-500 years. But a collision between any pair of satellites would have been reported on the news, and if we take 6000 as the number of satellites orbiting Earth, the number of pairs would be 5999+5998+...+1=18 million. Obviously it is much more likely than not for two randomly-picked satellites to have orbits that never intersect, but when the number of chances for failure is in the millions, one would expect something to happen pretty often. --Bowlhover (talk) 04:04, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- It would happen pretty often if measures weren't taken to avoid it. I'm not sure how often collision avoidance manoeuvres are made, but I know they certainly happen. --Tango (talk) 14:57, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- Wow - at those speeds, the odds of a collision with 90 degree orbital inclination is astoundingly small. The circumpherence of those orbits is around 40 million meters - if the spacecraft are (say) 10 meters long - then the odds of them colliding - even if their orbits do intersect is about 8 million to one against per orbit. At 8,000 m/s orbital speeds - each orbit takes a couple of hours - so you'd expect a collision like this about once every 400 to 500 years - even if they were both at the exact same altitude! SteveBaker (talk) 23:56, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

As I suggested above, there could be an international convention that any country or group launching a satellite is liable for any collisions it causes with preexisting and still functioning satellites. A defunct satellite could be seized and deorbitted by a robotic retrieval satellite, at the expense of the party launching the dud, to avoid the proliferation of space junk. So it is not correct that "There is little Russian Space Forces could have done." The U.S has discussed robotic deorbitting of the Hubble Space Telescope, for instance. Edison (talk) 14:47, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- Such a deorbitting mission would be very expensive and would take significant time to plan. It seems that these satellites were in polar orbits - it would be next to impossible to arrange polar orbiting satellites in such a way that their orbits never intersected any other satellite. Better tracking of satellites seems to be the answer - the commercial satellite was operational and should have been able to avoid the collision if it had been predicted. At those speeds a tiny course correction just a hour or so before the collision would probably be enough. --Tango (talk) 14:57, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

Have scientists tried mixing every combination of chemicals, elements, etc. together?

[edit]Or do they work this out mathematically, because of the obvious dangers? Maybe this sounds impractical. I just figured that most scientists felt they had a duty to uncover and report every secret that nature has tucked away in it's emergent property quantum realm. And to find out what blows up and shit.TinyTonyyy (talk) 22:11, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I just love how the question ends with "..and shit.". -Pete5x5 (talk) 00:42, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

- No to both questions. First off, over 40 million CAS registry numbers have been assigned to known compounds, so combining

any twoall possible pairs (without even considering such variables as temperature and pressure) would be an daunting task. And I'm fairly certain that modeling reactions computationally is quite difficult (otherwise drug companies would have a much easier job). Clarityfiend (talk) 23:05, 13 February 2009 (UTC) - There is often more to producing compounds than just mixing chemicals. There are certainly new compounds being discovered all the time (check out a Chemistry journal sometime), so they can't have got them all yet! --Tango (talk) 23:17, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Two more things to consider why it's an emphatic no. Even things that have been combined before sometimes create different compounds under different conditions. Think of temperature, distribution, pressure, agitation and the like. Even computer modeling doesn't help getting things down to size. Folding@home uses huge amounts of computer resources donated from all over the world and they aren't even combining anything. They are modeling at what proteins look like when they are folded in different ways. Depending on what's sticking out where they behave quite differently. 76.97.245.5 (talk) 00:24, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Imagine if you merely tried that with just a chemistry set containing 32 chemicals. How many mixtures would be required, ignoring order (with 1 to 32 components)? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1940s_Gilbert_chemistry_set_04.jpgEdison (talk) 00:43, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Like 32 with one chemical, 601,080,390 with 16 chemicals, etc. Edison (talk) 02:04, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- Imagine if you merely tried that with just a chemistry set containing 32 chemicals. How many mixtures would be required, ignoring order (with 1 to 32 components)? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1940s_Gilbert_chemistry_set_04.jpgEdison (talk) 00:43, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- In chemistry, atoms of elements combine to form moleculess. Depending on the type anbd position of th ebonds between the atoms, the same bunch of atoms can create completely differnt molecules ("chemicals") with completely different properties. Furthermore, there is no upper bound on the size of a molecule, so there are infinitely many different "chemicals." For example, there are zillions of different moleculres that are composed exclusively of atoms of carbon and hydrogen, and they have have radically different properties. These include gasses (methane, acetelene) liquids, (pentane, hexane, benzene) and solids (Paraffin.) So there are an infinite number of different molecular combinations of just these two elements. No, we have not yet discovered tehm all. -Arch dude (talk) 02:31, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- For a simple explanation of scale, say you have everyone in the world working to combine every pair in the CAS registry. There's 40 million of them, so that's 800 trillion. There are about 6.5 billion people, so that's over 100,000 pairs per person. If each person lives 70 years, that's about 25,000 days, so you'd have to have everyone in the world mix four chemicals a day for their entire lives. That's just every pair. If you want to mix every combination, that's 2^40 million, or about 10^12 million. For comparison, there's about 10^80 to 10^85 particles in the universe. — DanielLC 19:19, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- That's only scratching the surface though - many chemicals require three ingredients in order to react - or special temperature/pressure/agitation - some require specialized catalysts. Then you get things like polymers and proteins that form bit by bit rather than all at once. Truly, the number of possibilities is beyond measurement. Then you have isomers and isotopes. Isomers are chemicals with the exact same 'ingredients' - but different shapes. Something as simple as a benzene molecule can have several 'foldings' ("chair" and "boat" forms of the benzene ring) - others exist in left and right-handed forms - one of which will be biologically active and the other not. With proteins, this 'folding' is absolutely critical. There could be hundreds, thousands, maybe millions of "different" proteins that have identical formulae but are simply folded up differently and therefore have quite different properties. Then most elements have several stable isotopes (ie larger or fewer numbers of neutrons). These have very similar (but not identical) properties - so you might well find that to try everything, there would be a few odd versions of compounds that have the same formula but are built from unusual combinations of isotopes. So doing chemistry by making some of everything and testing it is a dead end. SteveBaker (talk) 03:08, 15 February 2009 (UTC)

Imagination "like becoming someone else" to some people?

[edit]My friend has Asperger's Syndrome, so I think I understand why he said this, but he recently remarked to me that when he tries to put himself in another person's shoes, he literally feels like he becomes that person, in a way. Even if it's someone in the past.

Is this because of the autism spectrum rendering normal imaginative play in children - and hence imagination in adults, I presume - hard if not impossible? So that a person with an ASD must practically feel like they become someone else to "imagine themselves" like that?

I'll note that I looked at the imagination article, and it's a little complex, but it almost seems like it's saying that is possible, since imagination is a created world.

Of course, I'll also grant that I probably shouldn't presume that he's using words in the same way I do, either.209.244.30.221 (talk) 22:12, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Somehow when I read your post I was immediately reminded of the writings of physicist Richard Feynman. Although certainly not in a field you'd think of in this regard he studied and described his ability to multitask. He compared that to what others described/displayed in that regard. People differ in their ability to e.g. listen and read at the same time. Some can write and speak at the same time. You can do your own experiments and compare your and your friend's results with Feynman's. While some people when reading a book hear the text read to them in their head, others see the words float off the page. So there is already a lot of variation in people not described as having any "syndrom" (or "disorder" :). If I'm not mixing things up I think I read that "Aspies" have a very visual memory. So your friend is probably creating a visual picture of the things he reads about in a book. Another thing usually described is the ability to "focus" excessively. So just the opposite of muuti-tasking. So your friend's brain may just not be able to process the information of the imaginary world and the real world at the same time. Empathy may interest you. I must say though that some of the things on that page rubbed me the wrong way. Our resident expert SteveBaker will probably be able to shed a lot more light on things. 76.97.245.5 (talk) 00:07, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

- My understanding is that the underlying cause of Aspergers and Autism (and other things along that spectrum) is most likely to be due to a failure or some kind of inadequacy of the mirror neurons. These neurons are the ones that let normal humans understand how other people are thinking by literally modelling a simplified version of their thought processes in your own head. I have Aspergers - and it seems almost like everyone else has some kind of telepathy that lets them all know what each other are feeling! This seems like magic to me! Kinda like the empathic Deanna Troi on Star Trek.

- The response your friend gives seems almost completely opposite to how I feel - which is that I'm simply unable to think about how someone else thinks or feels. I would speculate that perhaps your friend has discovered a way around not having a decent set of mirror neurons with which to model the other person's mental processes - but instead literally has to imagine that he is the other person and thereby use his regular neural capacity to model the other person's mental state. So for as long as he does this, he IS the other person. That's a very strange and interesting thing. If that is indeed what is going on, it would definitely be a neat trick...one that I'd very much like to learn. (Presuming it is learnable...not everything is).

- I suppose it's also possible that his diagnosis as an Asperger syndrome victim is incorrect.

- I'm autistic. I have put myself in people's shoes by pretty much imagining I was them, though I'm perfectly capable of empathy without that. I don't know if it works better, but it presumably varies how well it works with the person, so it's possible that your friend finds that it works much better, and does that a lot. When I read, I imagine what it sounds like, so there's at least one Aspie with auditory memory, though I don't see how that's relevant. Also, I don't have any problem imagining things. In fact, I commonly have a problem of getting lost in my thoughts, and imagining stuff when I should be doing something. — DanielLC 19:08, 14 February 2009 (UTC)

Error measurement question

[edit]The manual for the equipment says "Accuracy specifications are given as: ±([% of reading] + [number of least significant digits])". Then it gives, for example for one measurement, "0.5% +/- 1". Does that mean I have to multiply 0.5% by my measurement, then add 1? But where does the number of least significant digit come into the calculation?128.163.224.240 (talk) 22:30, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- That kind of expression is usually found on instruments that have a digital readout and is due to an uncertainty in the last digit which is present no matter what the size of the reading. For instance, consider a frequency counter with a six-digit display reading 173.624 MHz. An error of ±0.5% is ±86,812 Hz. To this must be added the uncertainty of the last digit, which in this case represents kHz (1000 Hz) so a ±1 uncertainty corresponds to ±1000 Hz making the total accuracy limits ±87,812 Hz. We can round this to ±88 kHz since the instrument on its current range is only measuring to a resolution of 1 kHz, making the limits for the measurement 173.536-173.712 MHz. SpinningSpark 23:31, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

Isaac Asimov quote on the fractal nature of discovery

[edit]Can anyone point me to the quote of Asimov's in which he talks about how every discovery opens a whole new series of questions - he compares the process to the recursive nature of fractals.

Thanks Adambrowne666 (talk) 22:55, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- I believe that scientific knowledge has fractal properties; that no matter how much we learn; whatever is left, however small it may seem, is just as infinitely complex as the whole was to start with. That, I think, is the secret of the Universe.

- - Autobiography I, Asimov: A Memoir (pub. post. 1994) - Azi Like a Fox (talk) 23:51, 13 February 2009 (UTC)

- Wonderful. Thank you. Adambrowne666 (talk) 02:45, 14 February 2009 (UTC)