Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Language/2012 June 7

| Language desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < June 6 | << May | June | Jul >> | June 8 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Language Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is a transcluded archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

June 7

[edit]Commander of ancient ships that aren't triremes

[edit]If a trierarch is the commander of a trireme, what do you call the commander of a penteconter or a quinquereme, etc? 67.158.4.158 (talk) 04:59, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- I think a "trierarch" is more of a ceremonial title than simply the literal captain of a trireme. It's almost like calling any person in charge of a boat "captain" in English, even if that is not their actual military rank. For the other types of ships, I don't think there was a specific title, but the equivalent of the "person in charge of the boat" in Greek was the nauarchos (or navarch, to Latinize it). Adam Bishop (talk) 08:30, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

Now then, Lord Arthur, who dragged whom around the walls of what?

[edit]I'm reading this essay, and I'm having trouble understanding what the point of a particular aside is. I can't link you to the relevant paragraph, but search for the heading above in the text and you'll find it. Does this joke imply that this would have been a very easy question at the time "when the British universities were thoroughly corrupt", and so even a "dissolute young aristocrat" could have answered it easily? And does the author thus suggest that today it would be a difficult question, only answerable by someone with a "successful completion of a major in humanities"? That's the best interpretation I can come up with, but I find the whole aside very unclear. (I assume the answer is Achilles, Hector and Troy.) 67.164.156.42 (talk) 08:00, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Yes and yes. And yes, yes, "the walls of Troy", if you want to get a First. Of course, Lord Arthur would probably be at a loss to explain who James KIrk is, or even how to operate the remote control of the satellite receiver. So this is more an indication of a shift in culture (some might even call it progress) than of our impending descent into the next Dark Ages. But it's more fun to rant. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 08:20, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

He's referring to a very simple question for someone who "benefited from a classical education", being sufficient for someone to gain entrance on the nod to the great educational establishments because of their pedigree, not their erudition, unlike the rest of society, who would have to pass the exam properly. You might like to see Winston Churchill's genuinely hilarious account of his entrance examination for Harrow School. You can see a version of it here. --Dweller (talk) 08:46, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- According to Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves failed to get into most English "public" schools because he couldn't conjugate the Greek verbs ιημι and ιστημι in the accepted manner, and instead had to go to Charterhouse, which he disliked intensely... AnonMoos (talk) 11:51, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

Latin case marking and subject/object ambiguity

[edit]Our Latin declension article identifies several Latin nouns which are identical in the nominative and accusative case. Since Latin has free word order, wouldn't there be considerable ambiguity if two such words occurred in a sentence with a transitive verb? How, in practice, were such ambiguities resolved, or did the Romans just avoid them by choosing words carefully? 69.107.248.119 (talk) 18:06, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Although Latin grammar does allow for a variety of word orders, the default structure of a sentence is SOV (subject, object, verb), so it stands to reason that this order was used in ambiguous cases. In most cases however, context would allow for the distinction of subject and object. - Lindert (talk) 18:26, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Agree with Lindert -- in most cases it would merely be a barrier to possible rearrangement of words into unusual orders (for poetic stylistic effects, or to place discourse emphasis), but not a problem for basic communication... AnonMoos (talk) 18:32, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Pragmatics will also often have played a role; in context, you can usually tell what's the subject and what's the object. Homines momorderunt canes is far more likely to be OVS than SVO simply because of what it means. Angr (talk) 19:00, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Totally agree with these answers, and as a long-time, struggling student of Latin, I can say it is the source of many an ambiguity for the novice reader. Still, when you look up the official translation, regardless of how poetic (and hence conversationally unnatural) the source, regardless of how free the word order, the answer begins to look like the only reasonable one. Somehow, the language works, although I have never figured out how it is possible. IBE (talk) 15:15, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- Pragmatics will also often have played a role; in context, you can usually tell what's the subject and what's the object. Homines momorderunt canes is far more likely to be OVS than SVO simply because of what it means. Angr (talk) 19:00, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Agree with Lindert -- in most cases it would merely be a barrier to possible rearrangement of words into unusual orders (for poetic stylistic effects, or to place discourse emphasis), but not a problem for basic communication... AnonMoos (talk) 18:32, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- You could say virtually the same thing about English, with all its exceptions and illogicalities and absurd spellings and pronunciations and homophones and homonyms and homographs and heteronyms. But somehow, it not only works, it has become more or less the lingua franca of the entire world. -- -- ♬ Jack of Oz ♬ [your turn] 23:01, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- German is somewhat similar, with case marking only revealing the case of masculine singular verbs, but they mix up the word order when they can, and keep it fixed when they can't. --Colapeninsula (talk) 09:27, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- I remember this confused me when I first started learning Latin, whenever I encountered a third-declension neuter that looked like a second-declension masculine - I'm sure I remember seeing exactly what you're talking about with the word "vulnus", but I don't remember where I read it. Adam Bishop (talk) 12:18, 9 June 2012 (UTC)

- Oh, this reminds me, I was once teaching a Renaissance text (I think it was De genealogia deorum gentilium), where there are a whole bunch of accusative neuter plurals that look like feminine singulars - "concordantia", etc. It's not the first-declension singular noun "concordance/agreement", it's the third-declension plural "(neuter) things that are in agreement". In that case I'm sure Boccaccio was making the text difficult to read just to show off. Adam Bishop (talk) 21:04, 10 June 2012 (UTC)

Italian phonotactics

[edit]

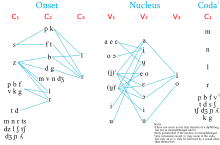

Hello, everyone. I was rather flustered and intimidated by the tables and descriptions of phonotactics in phonology articles, so I decided to create a softer, less technical diagram. I first tried to make one for English, but that proved too difficult, so I used the information in Italian phonology#Phonotactics to create the image you see. I thought I'd get some feedback here before adding it to the article. Interchangeable 18:29, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- It could probably be simplified with some structural grouping -- e.g. changing the fact that the cluster [kl] has nothing in common with [skl] in the diagram -- they now follow completely separate paths. There was a classic English syllable phonotactics diagram apparently published in a paper by Whorf in the 1940's showing the path through an English syllable (with "s" on the left and "s, st, t" and voiced variants on the right), which might give you some ideas, but it doesn't seem to be on-line. AnonMoos (talk) 19:23, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Sorry, what do you mean? The onsets [kl] and [skl] are supposed to be completely separate; they are different allowed onsets in Italian. I'm not even sure whether you want me to change the C1 level or the C2 level of the [kl] onset. Interchangeable 22:35, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- Well, all allowed sXY clusters (where "X" and "Y" are two consonants) have a corresponding alllowed XY cluster (without the "s" sound), right? Presumably that's not an accident. If it was possible to treat both sets together in the diagram, then it would be simpler and less "spaghetti-ish" (fewer crossing lines). For a version of Whorf's old English syllables diagram, see the end of http://hum.uchicago.edu/~jagoldsm/Papers/syllables.pdf .. AnonMoos (talk) 23:46, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- I find that more confusing than my diagram. Interchangeable 02:16, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- However, a similar diagram for Italian would be much simpler than the "Whorf onset diagram" for English, and with a little work, you could probably cut down a little on the Finite State Machine formalism and come up with a reasonably easy-to-understand diagram with no crossing lines... AnonMoos (talk) 08:23, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

P.S. One basic useful simplification (if you don't want to rethink the whole diagram from scratch) would be to group the second consonant of a three-consonant cluster together with the first consonant of a two-consonant cluster (and then of course the third consonant of a three-consonant cluster together with the second consonant of a two-consonant cluster), except for those two-consonant clusters beginning with s or z. Then you would find only s and z in first position, and only l and r in third position... AnonMoos (talk) 09:49, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- OK, I uploaded a quick-and-dirty diagram (File:Italian syllable onset phonotactics diagram.gif) which has drastically fewer crossing lines. (Sorry I didn't make it vector, but that would have taken me about three times as long.) It overgenerates a few sequences which are not in the original description (zvr, zvl, zgl), but then almost all such diagrams for English syllables overgenerate "stw"... It could be made a little more complicated to fix this minor flaw, if felt to be necessary. AnonMoos (talk) 12:28, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- Wow; that diagram is great! I'll remake it as a vector graphic (with some minor corrections, of course) and then add it to the article. Interchangeable 23:16, 10 June 2012 (UTC)

Oil-oc continuum?

[edit]I bought an odd book that asserts that the Marchois dialect is intermediate between langue d'oc and langue d'oil. Could there be anything in this? We have no article on Marchois but the Auvergnat article goes into the same discussion in a pretty incomprehensible way. Could there be a dialect continuum all the way thru France rather than the oil/oc boundary announced by signs on the motorways? Itsmejudith (talk) 23:31, 7 June 2012 (UTC)

- There definitely is...both the Langues d'oc and Langues d'oïl articles describe them as continuums, and there are several other intermediate languages along the way (Gallo, Arpitan...) Adam Bishop (talk) 06:43, 8 June 2012 (UTC)

- Thanks very much. The book is defensive in its claim of an intermediate status for Marchois. And I think there may be some Occitan nationalist agenda (rather understandably wanting to impose itself against state Jacobinism), in an insistence on the separation of oc and oil. I'll try and read up more on this continuum/divide. Itsmejudith (talk) 15:45, 8 June 2012 (UTC)