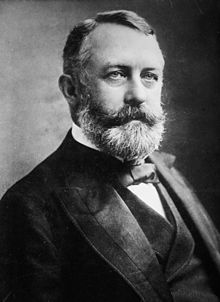

Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 19, 1849 |

| Died | December 2, 1919 (aged 69) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Homewood Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Education | Otterbein University (did not graduate) |

| Occupation(s) | Industrialist and art collector |

| Known for | Strikebreaking, Frick Collection, Johnstown Flood |

| Spouse | Adelaide Childs Frick (1859–1931) |

| Children | Childs Frick, Martha Frick, Helen Clay Frick, Henry Clay Frick Jr. |

| Signature | |

| |

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company and played a major role in the formation of the giant U.S. Steel manufacturing concern. He had extensive real estate holdings in Pittsburgh and throughout the state of Pennsylvania. He later built the Neoclassical Frick Mansion in Manhattan (now designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark), and upon his death donated his extensive collection of old master paintings and fine furniture to create the celebrated Frick Collection and art museum. However, as a founding member of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, he was also in large part responsible for the alterations to the South Fork Dam that caused its failure, leading to the catastrophic Johnstown Flood. His vehement opposition to unions also caused violent conflict, most notably in the Homestead Strike.

Early life

[edit]Frick was born in West Overton, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, in the United States, a grandson of Abraham Overholt (Oberholzer), the owner of the prosperous Overholt Whiskey distillery (see Old Overholt).[1] His father was of Swiss ancestry; his mother was of German ancestry.[2][3] Frick's father, John W. Frick, was unsuccessful in business pursuits. Henry Clay Frick attended Otterbein College for one year, but did not graduate.[4] In 1871, at 21 years old, Frick joined two cousins and a friend in a small partnership, using a beehive oven to turn coal into coke for use in steel manufacturing, and vowed to be a millionaire by the age of thirty. The company was called Frick Coke Company.[5]

Thanks to loans from the family of lifelong friend Andrew Mellon, by 1880, Frick bought out the partnership. The company was renamed H. C. Frick & Company, employed 1,000 workers and controlled 80 percent of the coal output in Pennsylvania,[5] operating coal mines in Westmoreland and Fayette counties, where he also operated banks of beehive coke ovens. Some of the brick and stone structures are still visible in both Fayette and Westmoreland Counties.

H. C. Frick and Andrew Carnegie

[edit]Shortly after marrying Adelaide Howard Childs,[6] in 1881, Frick met Andrew Carnegie in New York City while the Fricks were on their honeymoon. This introduction would lead to an eventual partnership between H. C. Frick & Company and Carnegie Steel Company and, eventually, to United States Steel. This partnership ensured that Carnegie's steel mills had adequate supplies of coke. Frick became chairman of the company. Carnegie made multiple attempts to force Frick out of the company they had created by making it appear that the company had nowhere left to go and that it was time for Frick to retire. Despite the contributions Frick had made towards Andrew Carnegie's fortune, Carnegie disregarded him in many executive decisions including finances.[7]

The Johnstown Flood

[edit]At the suggestion of his friend Benjamin Ruff, Frick helped to found the exclusive South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club high above Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The charter members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club were Benjamin Ruff; T. H. Sweat, Charles J. Clarke, Thomas Clark, Walter F. Fundenberg, Howard Hartley, Henry C. Yeager, J. B. White, Henry Clay Frick, E. A. Meyers, C. C. Hussey, D. R. Ewer, C. A. Carpenter, W. L. Dunn, W. L. McClintock, and A. V. Holmes.[8]

The sixty-odd club members were the leading business tycoons of Western Pennsylvania, and included among their number Frick's best friend, Andrew Mellon, his attorneys Philander Knox and James Hay Reed, as well as Frick's occasional business partner Andrew Carnegie. The club members made inadequate repairs to what was at that time the world's largest earthen dam, behind which formed a private lake called Lake Conemaugh. Less than 20 miles (32 km) downstream from the dam sat the city of Johnstown. Cambria Iron Company operated a large iron and steel work in Johnstown and its owner, Daniel J. Morrell, was concerned about the safety of the dam and the thoroughness of repairs made to it.

The Club fatally lowered the dam by between 0.6 and 0.9 metres (2.0 and 3.0 ft).[9] Poor repairs and maintenance, unusually high snow melt and heavy spring rains combined to cause the dam to give way on May 31, 1889, resulting in the Johnstown Flood. A screen placed across the spillway by the club to prevent fish from escaping also partly blocked the main spillway.[10] When word of the dam's failure was telegraphed to Pittsburgh, Frick and other members of the club gathered to form the Pittsburgh Relief Committee for assistance to the flood victims, as well as determining never to speak publicly about the club or the flood. This strategy was a success, and Knox and Reed were able to fend off all lawsuits that would have placed blame upon the club's members. With a volumetric flow rate that temporarily equalled that of the Mississippi River,[11] the flood killed 2,208 people[12] and caused US$17 million of damage (about $450 million in 2015 dollars).

The American Society of Civil Engineers launched an investigation of the South Fork Dam breach immediately after the flood. However, the report was delayed, subverted, and whitewashed, before being released two years after the disaster. A detailed discussion of what happened during the ASCE investigation, its participating engineers, and the science behind the 1889 flood was published in 2018.[13]

Old Overholt whiskey

[edit]In 1881, Frick, already wealthy, took control of his grandfather's whiskey company, Old Overholt.[14] Frick split ownership with Andrew Mellon and Charles W. Mauck; each owned one-third of the company.[14] The family's whiskey company was a sentimental side business for Frick,[14] and was headquartered in Pittsburgh's Frick Building.[15] In 1907, as prohibition became more popular across the country, Frick and Mellon removed their names from the distilling license, although they retained ownership in the company.[15] Upon Frick's death in 1919, he left his share of the company to Mellon.[15]

Homestead strike

[edit]

Frick and Carnegie's partnership was strained over actions taken in response to the Homestead Steel Strike, an 1892 labor strike at the Homestead Works of the Carnegie Steel Company, called by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers.[5] At Homestead, striking workers, some of whom were armed, had locked the company staff out of the factory and surrounded it with pickets. Frick was known for his anti-union policy and as negotiations were still taking place, he ordered the construction of a solid board fence topped with barbed wire around mill property. The workers dubbed the newly fortified mill "Fort Frick." With the mill ringed by striking workers, Pinkerton agents planned to access the plant grounds from the river. Three hundred Pinkerton detectives[5] assembled on the Davis Island Dam on the Ohio River about five miles (8 km) below Pittsburgh at 10:30 p.m. on the night of July 5, 1892. They were given Winchester rifles, placed on two specially-equipped barges and towed upriver with the object of removing the workers by force. Upon their landing, a large mêlée between workers and Pinkerton detectives ensued. Ten men were killed, nine of them workers, and there were seventy injuries.[5][16] The Pinkerton agents were thrown back, and the riot was ultimately quelled only by the intervention of 8,000 armed state militia under the command of Major General George R. Snowden.[16] During the confrontation Frick issued an ultimatum to Homestead workers, which restated his refusal to speak with union representatives and threatened to have striking workers evicted from their homes.[16]

Among working-class Americans, Frick's actions against the strikers were condemned as excessive, and he soon became a target of even more union organizers. Because of this strike, people like Alan Petrucelli had thought that he is depicted as the "rich man" in Maxo Vanka's murals in St. Nicholas Croatian Church, but the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka (which works to preserve the artwork) says it depicts Andrew Mellon.[17]

Assassination attempt

[edit]

In 1892, during the Homestead strike, anarchist Alexander Berkman attempted to assassinate Frick. On July 23, Berkman, armed with a revolver and a sharpened steel file, entered Frick's office in downtown Pittsburgh.[5]

Frick, realizing what was happening, attempted to rise from his chair while Berkman pulled a revolver and fired at nearly point-blank range. The bullet hit Frick in the left earlobe, penetrated his neck near the base of the skull, and lodged in his back. The impact knocked Frick down, and Berkman fired again, striking Frick for a second time in the neck and causing him to bleed extensively. Carnegie Steel vice president (later, president) John George Alexander Leishman, who was with Frick, was then able to grab Berkman's arm and prevented a third shot, possibly saving Frick's life.

Frick was seriously wounded but rose and (with the assistance of Leishman) tackled his assailant.[18] All three men crashed to the floor, where Berkman managed to stab Frick four times in the leg with the pointed steel file before finally being subdued by other employees and a carpenter, who had rushed into the office.

Frick was back at work within a week; Berkman was charged and found guilty of attempted murder. Berkman's actions in planning the assassination clearly indicated a premeditated intent to kill, and he was sentenced to 22 years in prison.[5] Negative publicity from the attempted assassination resulted in the collapse of the strike.[19]

Private life

[edit]

Frick married Adelaide Howard Childs of Pittsburgh on December 15, 1881. They had four children: Childs Frick (born March 12, 1883), Martha Howard Frick (born August 9, 1885), Helen Clay Frick (born September 3, 1888) and Henry Clay Frick, Jr. (born July 8, 1892). In 1882, after the formation of the partnership with Andrew Carnegie, Frick and his wife bought a home they eventually called Clayton, an estate in Pittsburgh's East End. They moved into the home in early 1883. The Frick children were born in Pittsburgh and were raised at Clayton. Two of them, Henry, Jr. and Martha, died in infancy or childhood.[20]

In 1904, he built Eagle Rock, a summer estate at Prides Crossing in Beverly, Massachusetts on Boston's fashionable North Shore. The 104-room mansion designed by Little & Browne was razed in 1969.[21]

Frick was a fervent art collector whose wealth allowed him to accumulate a large collection.[22] By 1905, Frick's business, social and artistic interests had shifted from Pittsburgh to New York. He took his art collection with him to New York, rented the William H. Vanderbilt House, and served on many corporate boards.

For example, as a board member of the Equitable Life Insurance Company, Frick attempted the removal of James Hazen Hyde (the founder's only son and heir) from the United States to France by seeking an appointment for him to become United States Ambassador to France. Frick had engaged a similar stratagem when orchestrating the ouster of the man who had saved his life, John George Alexander Leishman, from the presidency of Carnegie Steel a decade beforehand. In that instance, Leishman had chosen to accept the post as ambassador to Switzerland. Hyde, however, rebuffed Frick's plan. He did, however, move to France, where he served as an ambulance driver during World War I and lived until the outbreak of World War II.

The Frick Collection is home to one of the finest collections of European paintings in the United States. It contains many works of art dating from the pre-Renaissance up to the post-Impressionist eras, displayed at the Henry Clay Frick House (built in 1913) in no logical or chronological order. It includes several very large paintings by J. M. W. Turner and John Constable. In addition to paintings, it also contains an exhibition of carpets, porcelain, sculptures, and period furniture.

Frick purchased the Westmoreland, a private railroad car, from the Pullman Company in 1910. The car cost nearly $40,000, and featured a kitchen, pantry, dining room, servant's quarters, two staterooms, and a lavatory. Frick frequently used the car for travel between his residences in New York City, Pittsburgh, and Prides Crossing, Massachusetts, as well for trips to places such as Palm Beach, Florida, and Aiken, South Carolina. The car remained in the Frick family until it was scrapped by Helen Clay Frick in 1965. Photographs of family and friends travelling on the Westmoreland form part of the Frick archive, as do the original construction plans and upholstery fabric samples.[23][24]

Frick and his wife Adelaide had booked tickets to travel back to New York on the inaugural trip of the RMS Titanic in 1912, along with J.P. Morgan. The couple canceled their trip after Adelaide sprained her ankle in Italy and missed the disastrous voyage.[25]

Frick died of a heart attack on December 2, 1919, at age 69.[26] He was buried in Pittsburgh's Homewood Cemetery.[27]

Legacy

[edit]

Frick left a will in which he bequeathed 150 acres (0.61 km2) of undeveloped land to the City of Pittsburgh for use as a public park, together with a $2 million trust fund to assist with the maintenance of the park. Frick Park opened in 1927. Between 1919 and 1942, money from the trust fund was used to enlarge the park, increasing its size to almost 600 acres (2.4 km2).

Many years after her father's death, Helen Clay Frick returned to Clayton in 1981, and lived there until her death in 1984.

Frick was elected an honorary member of the Alpha chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia music fraternity at the New England Conservatory of Music on October 19, 1917.[27]

Henry Clay Frick Business Records (Archives)

[edit]The Henry Clay Frick archive of business records consisted of the documents regarding the business and financial dealings from 1849 to 1919. These original documents record the evolution of the period of American steel and coal industrial growth. Documentation includes first business activities, first coal firm, H.C. Frick & Company, to the formation of United States Steel Corporation on March 2, 1901. Correspondence sent and received from prominent businessmen such as Andrew Carnegie, Charles Schwab, Andrew Mellon, Henry Oliver, H. H. Rogers, Henry Phipps, and J. P. Morgan are part of the collection. Much of the collection is available as digitized and openly accessible. Most of the collection is from 1881 to 1914, and is relevant to the history of the Pittsburgh region.[28]

The archive of Frick's great-grandfather, Henry Overholt (1739–1813), is also housed at the Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh Library System, University of Pittsburgh.[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Helen Clay Frick Foundation Archives Finding Aid". Guides to Archives and Manuscript Collections at the University of Pittsburgh Library System. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Erasmus Wilson (1898). Standard History of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, Volume 1. Chicago: H.R. Cornell & Company. p. 1039.

- ^ Distinguished Biographers, Selected from Each State, Revised and Approved by The Most Eminent Historians, Scholars and Statesmen of The Day (1900). The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Volume 10. New York: James T. White Company. p. 203.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Founded His Fortune in the Panic of 1873"

- ^ a b c d e f g Candace Falk; Barry Pateman; Jessica M. Moran (2003). "Sample short biographies". Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, 1890–1901. University of California Press. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ "Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919)". Frick Art & Historical Center (Pittsburgh). Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ^ www.n-state.com, NSTATE, LLC. "Henry Clay Frick - People of Pennsylvania". www.netstate.com. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Court of Common Pleas (November 17, 1879). "Charter of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club". p. 7. Retrieved September 29, 2018 – via Digital Public Library of America.

- ^ Coleman, Neil M.; Kaktins, Uldis; Wojno, Stephanie (2016). "Dam-Breach hydrology of the Johnstown flood of 1889–challenging the findings of the 1891 investigation report". Heliyon. 2 (6): e00120. Bibcode:2016Heliy...200120C. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00120. PMC 4946313. PMID 27441292. e00120.

- ^ "The Johnstown Flood, May 31, 1889". glessnerhouse.org. Chicago, IL: Glessner House Museum. May 26, 2014. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Sid Perkins, "Johnstown Flood matched volume of Mississippi River" Archived September 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Science News, Vol.176 #11, November 21, 2009, accessed October 14, 2012

- ^ Gibson, Christine. "Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters". American Heritage (August/September 2006). Archived from the original on December 5, 2010.

- ^ Coleman, Neil M. (2018). Johnstown's Flood of 1889 - Power Over Truth and the Science Behind the Disaster. Springer International AG. ISBN 978-3-319-95215-4.

- ^ a b c Wondrich, David (September 2, 2016). "The Rise & Fall of America's Oldest Whiskey". The Daily Beast. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c Wondrich, David (September 12, 2016). "How Pennsylvania Rye Whiskey Lost Its Way". The Daily Beast. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c Tuchman 1996, p.82

- ^ Petrucelli, 2008.

- ^ Krause, 1992, p. 354.

- ^ Krause, 1992, p. 355.

- ^ Skrabec, 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Lowry, Patricia (December 18, 2001). "Book assesses Frick family houses, both inside and out". Pittsburgh Post Gazette. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ Quodbach, Esmée (2009). ‘I want this collection to be my monument’: Henry Clay Frick and the formation of The Frick Collection, Journal of the History of Collections, V. 21 (November): 229–240.

- ^ "selections from the Helen Clay Frick Foundation Archives" (PDF). Helen Clay Frick Foundation.

- ^ Hughes, Edith (2010), "The 'Westmoreland' was a Mansion on Wheels", Westmoreland History, 15 (1): 4–6

- ^ Daugherty, Greg (March 2012). "Seven Famous People who Missed the Titanic". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- ^ "Henry C. Frick Dies". The New York Times, December 3, 1919.

- ^ a b "Memory and Mourning: A Frick History of Homewood Cemetery". The Frick Pittsburgh. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Henry Clay Frick Business Records, Guides to Archives and Manuscript Collections at the University of Pittsburgh Library System". University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Abraham Overholt & Company, 1881–1888, Guides to Archives and Manuscript Collections at the University of Pittsburgh Library System. University of Pittsburgh.

Bibliography

[edit]- Falk, Candace; Pateman, Barry; and Moran, Jessica M. Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2003.

- "Founded His Fortune in the Panic of 1873". The New York Times, December 3, 1919.

- "Henry C. Frick Dies". The New York Times, December 3, 1919.

- Krause, Paul. The Battle for Homestead, 1890–1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992.

- Petrucelli, Alan W. "A Fresh Look: Viewing Vanka Murals a Religious Experience." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 14, 2008.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. Henry Clay Frick: The Life of the Perfect Capitalist. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2010.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1996). The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War: 1890–1914. The Macmillan Company. ISBN 0333306465.

Further reading

[edit]- Apfelt, Brian. The Corporation: 100 Years of the United States Steel Corp.

- Harvey, George. Henry Clay Frick: The Man (1928), an authorized biography by a close friend. online

- Hessen, Robert. Steel Titan: The Life of Charles M. Schwab. (1975)

- Sanger, Martha Frick Symington. Henry Clay Frick: An Intimate Portrait. New York: Abbeville Press, 1998.

- Sanger, Martha Frick Symington. The Henry Clay Frick Houses: Architecture, Interiors, Landscapes in the Golden Era. New York: Monacelli Press, 2001.

- Skrabec Jr, Quentin R. Henry Clay Frick: The life of the perfect capitalist (McFarland, 2010). online

- Skrabec Jr, Quentin R. The Carnegie Boys: The Lieutenants of Andrew Carnegie that Changed America (McFarland, 2012) online.

- Smith, Roberta. "Change Arrives on Tiptoes at the Frick Mansion". The New York Times, August 28, 2008.

- Standiford, Les. Meet You in Hell: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and the Bitter Partnership That Transformed America. New York: Crown Publishers, 2005.

- Warren, Kenneth. Triumphant Capitalism: Henry Clay Frick and the Industrial Transformation of America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996; the standard scholarly biography.

- Warren, Kenneth. "The Business Career of Henry Clay Frick". Pittsburgh History vol. 73, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 3–15.

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Official Frick Collection Website

- The Frick Art & Historical Center and Clayton

- Henry Clay Frick at Find a Grave

- Helen Clay Frick Foundation Archives

- Finding Aid for the Adelaide H.C. Frick Papers, 1874-1951

- Documenting the Gilded Age: New York City Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century A New York Art Resources Consortium project.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Frick, Henry Clay". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1918.

- "Frick, Henry Clay". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- 1849 births

- 1919 deaths

- American industrialists

- American people of German descent

- American people of Swiss descent

- American manufacturing businesspeople

- American shooting survivors

- American steel industry businesspeople

- People associated with the Frick Collection

- Museum founders

- Frick Art Research Library

- Andrew Carnegie

- Burials at Homewood Cemetery

- People from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania

- Gilded Age

- Pittsburgh Labor History

- Stabbing survivors

- U.S. Steel people