James Hazen Hyde

James Hazen Hyde | |

|---|---|

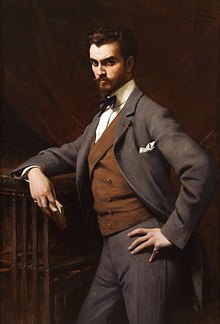

Portrait, 1901 | |

| Born | June 6, 1876 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1959 (aged 83) |

| Education | Cutler School |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Spouse(s) |

Marthe, Countess de Gontaut-Biron

(m. 1913; div. 1918) |

| Children | Henry Baldwin Hyde II |

| Parent(s) | Annie Fitch Hyde Henry Baldwin Hyde |

| Awards | Grand-Croix de la Legion d'honneur |

James Hazen Hyde (June 6, 1876 — July 26, 1959) was the son of Henry Baldwin Hyde, the founder of The Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States. James Hazen Hyde was twenty-three in 1899 when he inherited the majority shares in the billion-dollar Equitable Life Assurance Society.[1] Five years later, at the pinnacle of social and financial success, efforts to remove him from The Equitable set in motion the first great Wall Street scandal of the 20th century, which resulted in his resignation from The Equitable and relocation to France.[2]

Early life

[edit]James Hazen Hyde was born in New York City on June 6, 1876. He was the only surviving son of Henry Baldwin Hyde and Annie (née Fitch) Hyde.[3][4] His older sister was Mary who was married to Sidney Dillon Ripley in 1886. After Ripley's death in 1905, she married banker Charles R. Scott in 1912.[5]

He graduated from the Cutler School, and received his degree from Harvard University in 1898. Hyde studied French history, language and literature, and was involved in efforts to establish an exchange program that enabled French authors and educators to lecture at universities in the United States, with American professors reciprocating at universities in France. Hyde's efforts included the endowment of a fund to defray professor's expenses, and he received the Legion of Honor (Chevalier) from the government of France.[6]

Career

[edit]Hyde was appointed a vice president of The Equitable after graduating from college. In addition, he served on the boards of directors of more than 40 other companies, including the Wabash Railroad and Western Union.[7]

Besides his business activities, Hyde pursued several other hobbies and pastimes. His homes included a large estate on Long Island, where Hyde maintained horses, stables, roads, and trails to engage in coach racing. In addition to coach racing, he also took part in horse shows and horse racing. Hyde accumulated a collection of coaches and carriages, which he later donated to the Shelburne Museum.[7]

Removal from The Equitable

[edit]

Following his father's death, Hyde was the majority shareholder and in effective control of The Equitable.[8] By the terms of his father's will,[9] he was scheduled to assume the presidency of the company in 1906.[10] Members of the board of directors, including E. H. Harriman, Henry Clay Frick, J.P. Morgan, and company President James Waddell Alexander attempted to wrest control from Hyde through a variety of means, including an unsuccessful attempt to have him appointed as Ambassador to France.[11][12][13]

On the last night of January 1905, Hyde hosted a highly publicized Versailles-themed costume ball.[14] Falsely accused through a coordinated smear campaign initiated by his opponents at The Equitable of charging the $200,000 party ($6,782,000 today) to the company, Hyde soon found himself drawn into a maelstrom of allegations of his corporate malfeasance.[15] The allegations almost caused a Wall Street panic, and eventually led to a state investigation of New York's entire insurance industry, which resulted in laws to regulate activities between insurance companies, banks and other corporations.[16]

Hyde's personal net worth in 1905 was about $20 million ($678,200,000 today). After the negative press generated by the efforts to remove him from The Equitable, Hyde resigned from the company later that same year, gave up most of his other business activities, and moved to France.[17] There were published rumors that he would marry French actress Yvonne Garrick in 1906.[18]

World War I

[edit]At the start of World War I, Hyde converted his home and a Paris rental property into French Red Cross hospitals, and he volunteered his services as an organizer and driver with the American Field Ambulance Service. When the United States entered the war Hyde was commissioned as a Captain and assigned as an aide to Grayson Murphy, the High Commissioner of the American Red Cross in France.[7]

During and after the war Hyde also directed the Harvard and New England bureau of the University Union in Paris. Through this organization's auspices Hyde set up a series of annual lectures for American professors visiting French universities. He also helped win public support for aiding France by publishing several of his own lectures and monographs.[7]

Later life

[edit]

In 1941 Hyde returned from France as the result of Nazi Germany's occupation of France during World War II. In retirement he resided at the Savoy-Plaza Hotel in New York City and hotels in Saratoga Springs, New York.[6]

Personal life

[edit]In Paris on November 25, 1913, Hyde married Marthe (née Leishman) de Gontaut-Biron (1882–1944). The Countess de Gontaut-Biron, the widow of Count Louis de Gontaut-Biron, was a daughter of Ambassador John George Alexander Leishman and Julia (née Crawford) Leishman. Before their divorce in 1918, which was reportedly over her strong personal attachment to Germany and not the result of the involvement of another man or woman, they were the parents of:[19]

- Henry Baldwin Hyde II (1915–1997),[20] who married Marie de La Grange, a daughter of Baron Amaury De La Grange[21] and Emily Eleanor, Baroness De La Grange (daughter of Henry T. Sloane),[22] in 1941.[23] Marie's brother was musicologist Henry-Louis de La Grange, known for his biography of Gustav Mahler.[24]

His ex-wife died in 1944.[25] Hyde died in Saratoga Springs on July 26, 1959.[26][6] He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

Legacy and honors

[edit]Hyde was a collector of books and documents relating to Franco-American relations beginning in 1776. He was a member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, the American Antiquarian Society, and the New-York Historical Society. He formed a collection of allegorical prints illustrating the Four Continents that are now at the New-York Historical Society; Hyde's drawings and a supporting collection of sets of porcelain figures and other decorative arts illustrating the Four Continents were shared by various New York City museums.

For his efforts during the war, Hyde received the Grand-Croix de la Legion d'honneur.[27] He was granted an honorary degree by the University of Rennes in 1920.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Saxena, Jaya (January 28, 2013). "James Hazen Hyde: A Gilded Age Scandal". The New York History Blog. New-York Historical Society. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ "KILL FRICK REPORT IN BITTER FIGHT; Harriman, Frick, and Bliss Resign from Equitable. LEFT MEETING IN RAGE Hyde Accused First Two, Ingalls and Schiff. BETRAYED HIM, HE SAID Chairman of Board to Be Created to Direct Society -- Hyde to Relinquish Stock". The New York Times. 3 June 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "HOSPITALS TO GET $100,000.; Will of Mrs. Henry B. Hyde Divides This Sum Among Four". The New York Times. 29 June 1922. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Times, Special to The New York (13 April 1923). "Henry B. Hyde, Founder of Equitable Life, Left an Estate Valued at Only $1,771,762". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "MRS. CHARLES SCOTT DEAD IN PARIS AT 72; Daughter of Henry B. Hyde, Founder of Equitable Life". The New York Times. 4 September 1938. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Times, Special to The New York (27 July 1959). "James Hazen Hyde Dies at 83; Son of Founder of Equitable Life; Former Insurance Official Gave Lavish Party That Led to State Inquiry". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Larry Weimer, with Alec Ferretti, Jennifer Gargiulo, and Aaron Roffman. "Guide to the James Hazen Hyde Papers (1874-1940)". dlib.nyu.edu. New-York Historical Society. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "DEATH OF HENRY B. HYDE; Equitable Life's President Succumbs to Heart Disease. HAD BEEN ILL FOR ONE YEAR Career of the Man Who Organized the Assurance Society and Brought It to Its Present Position". The New York Times. 3 May 1899. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "HENRY B. HYDE'S WILL.; Value of the Estate Is Shown to be $530,000 -- Widow, Son, and Daughter the Principal Beneficiaries". The New York Times. 20 May 1899. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Adams, Susan (July 9, 2003). "After the Ball". Forbes magazine.

- ^ "HYDE TELLS HOW ODELL GOT EVEN; Threatened Trust Charter for His Shipyard Loss. PAY IT, SAID HARRIMAN So the Governor-Chairman Got Back His $75,000. HYDE FOR AMBASSADOR On Witness Stand He Says Frick Tried to Get Him Away to France -- Hits Harriman". The New York Times. 15 November 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "HARRIMAN DENIES HYDE TESTIMONY; Tells Different Story of Shipyard Settlement. ODELL WILL BE HEARD Dramatic Scene When Committee Tells Untermyer He Can't Cross-Examine Harriman. HARRIMAN DENIES HYDE TESTIMONY". The New York Times. 16 November 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "MADE NO THREAT, ODELL DECLARES; Saw No Objection to Charter Annulment Bill. BUT HAD IT WITHDRAWN This Because of His Shipbuilding Connection. TOOK MATTER TO JEROME Nothing to Prosecute on -- Harriman Only a "Social Friend" -- Depew Testifies". The New York Times. 17 November 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "JAMES H. HYDE GIVES SPLENDID COSTUME FETE; Sherry's Transformed Into 18th Century French Garden. MADAME REJANE IN PLAY Piece Written for Occasion by Dorio Niceodemi -- Old-Time Ballet Given by Dancers from Metropolitan". The New York Times. 1 February 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "HYDE SUES TO DEPOSE ALEXANDER AS TRUSTEE; Story of Indecent Dance at Hyde's Ball Attributed to Alexander. EQUITABLE CONTROVERSY, TOO Due to His Perfidy and Desire for Control, It Is Alleged -- Tarbell Called Co-conspirator". The New York Times. 13 May 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "VOTING POWER SOUGHT FOR POLICY HOLDERS; Plan of the Alexander Interests in the Equitable Life. JAMES H. HYDE'S CONTROL At Present It Rests with Him, Representing the Majority Stock Interest -- Petition from Office Holders". The New York Times. 14 February 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "ALL HYDE DIRECTIONS TO QUIT THE EQUITABLE; Merely That Morton May Have Free Hand -- May Return. BUT ASTOR WILL STAY OUT Ryan Trustees Considering Names to Fill Vacancies on the Board -- MaY Recommend Members To-day". The New York Times. 28 June 1905. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Hyde May Marry French Actress" Philadelphia Inquirer (December 9, 1906): 17. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Times, the New York Times Company Special Cable To the New York (1 December 1918). "JAMES HAZEN HYDE AND WIFE DIVORCED; Mrs. Hyde's Personal Attachment to Germany Leads to Decree in French Courts. HER MOTHER DIES ABROAD Mrs. Hyde Was a Daughter of J.G.A. Leishman, Ex-Ambassador to Germany. Death of Mrs. Leishman". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (8 April 1997). "Henry Hyde Is Dead at 82; Wartime Spymaster for O.S.S." The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Deaths" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 June 1953. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Baroness A. de la Grange, 93; Related to Sloane's Founder". The New York Times. 2 October 1981. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Miss de la Grange Becomes Bride Of Henry Hyde; Granddaughter of Late Henry T. Sloane Wed Here to Son Of James Hazen Hyde" (PDF). The New York Times. 20 April 1941. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (9 February 2017). "Henry-Louis de La Grange, Mahler Authority, Is Dead at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "MRS. MARTHE L. HYDE; Daughter of Late Diplomat Had Been Wife of James Hazen Hyde". The New York Times. 28 July 1944. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "James Hyde, 83, Retired Insurance Official, Dies". Times Record. Troy, N.Y. July 27, 1959.

- ^ "FRANCE HONORS AMERICANS; Confers "Medals of Gratitude" on Many for Their War Work". The New York Times. 8 March 1918. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

External links

[edit]- Patricia Beard (2004). After the Ball: Gilded Age Secrets, Boardroom Betrayals, and the Party That Ignited the Great Wall Street Scandal of 1905. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-095892-8.

- The James H. Hyde Collection of Allegorical Prints of the Four Continents at the New-York Historical Society

- James Hazen Hyde papers at New-York Historical Society