Western Zone, Tigray

Western Tigray | |

|---|---|

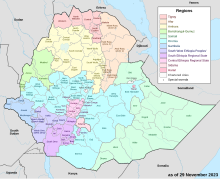

Western Zone location in Ethiopia | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Largest city | Humera |

| Area | |

• Total | 12,323.35 km2 (4,758.07 sq mi) |

| Population (2012 est.) | |

• Total | 407,560 |

| • Density | 33/km2 (86/sq mi) |

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (June 2024) |

The Western Zone (Tigrinya: ዞባ ምዕራብ) is a zone in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. It is subdivided into three woredas (districts); from north to south they are Kafta Humera, Welkait and Tsegede. The largest town is Humera. The Western Zone is bordered on the east by the North Western Zone, the south by the Amhara Region, the west by Sudan and on the north by Eritrea. Starting from the late 17th C., internal boundaries are clearly shown, with 37 maps (between 1683 and 1941) displaying a boundary that is located well south of the Tekeze River, or even south of the Simien mountains. Welkait is explicitly included within a larger Tigray confederation (periods 1707–1794; 1831–1886; and 1939–1941); it is briefly mapped as part of Amhara in 1891–1894 and part of Gondar from 1944 to 1990. At other periods it appears independent or part of a larger Mezaga ("dark earth") lowland region.[2]

Since November 2020, as part of the Tigray War, the administration of the Western Zone was taken over by officials from the Amhara Region.[3]

History

[edit]Edward Ullendorff in his book The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People,[4] states "Tigrigna – as the name implies – is a language of the Tigrai province. It is spoken throughout the Eritrean plateau and extends as far as lake Ashangai and the Wejerat districts, it then crosses the Takkaze westwards to the Tsellemti and Welkayt regions. And the people who speak this language at the authentic carriers of the historical and cultural traditions of the ancient Abyssinia".

Welkait, Tsegede, Kafta Humera (now called Western Tigray) and Tselemti in the North Western Zone are part of the Tigray polity. Starting from the late 17th C., internal boundaries are clearly shown, with 37 maps (between 1683 and 1941) displaying a boundary that is located well south of the Tekeze River, or even south of the Simien mountains. Welkait is explicitly included within a larger Tigray confederation (periods 1707–1794; 1831–1886; and 1939–1941); The areas were under the Gonder Province administration from 1944 to 1990. At times the areas were autonomous provinces ruled by Amhara nobles and other times fell under the administration of Begemder.[5][6]

Pre Axumite and Axumite kingdom

[edit]Geographical and anthropological evidence show that Western Tigray has been part of Tigray since Pre-Axumite times[7][8] also in the middle ages as is clearly stated in 1833 book by Michael Russell ''NUBIA and ABYSSINIA: Comprehending Their Civil History, Antiquities, Arts, Religion, Literature, and Natural history’’ at page 79 explicitly states that Semien, WElQait, Waldba, and Lasta were part of Tigray province.[9]

The mention of Säb’a Welkait (ሰብኣ-ወልቃይት) is analogous to and parallel with Säb’a Enterta or Enderta (Enderta or Enterta People), Säb’a Agame (Agame People), Säb’a Azebo (Azebo People), Säb’a Womberta (Womberta People), and Säb’a Segli (Segli People), Säb’a Wejjerat (Wejjerat people) and the like we see in historical sources. It is an exact reference defining people (Säb’a) in a certain domain (Welkait) under the polity (Aksumite identity). source Fattovich and Bard, 2001:4[7] and Hatsani Daniel mentions a toponym WYLQ Welkait from Western Tigray.[8] This fact is clearly stated in Michael Russell's 1833 book "NUBIA and ABYSSINIA: Comprehending Their Civil History, Antiquities, Arts, Religion, Literature, and Natural History" on page 79. According to the book, Semien, WelQait, Waldba, and Lasta were all part of the Tigray province.

Middle ages (1607–1944)

[edit]109 historical and 31 ethno-linguistic maps (1607–2014) compiled by the researchers in Ghent University in Belgium show that starting from the late 17th C., internal boundaries are clearly shown, with 37 maps (between 1683 and 1941) displaying a boundary that is located well south of the Tekeze River, or even south of the Simien mountains. Welkait is explicitly included within a larger Tigray confederation (periods 1707–1794; 1831–1886; and 1939–1941); it is briefly mapped as part of Amhara in 1891–1894 and part of Gondar from 1944 to 1990. At other periods it appears independent or part of a larger Mezaga ("dark earth") lowland region.[2] During the era of the princes, areas west of the Tekeze river was governed by Semien-based hereditary. Ras Gebre of Semien was the governor of Semien, Tsegede, Wolkait and Wogera, his long reign lasted 44 years and came to an end in 1815. His son Haile Maryam Gebre succeeded him and reigned between 1815 and 1826 and was succeeded by his son Wube.[10][11][12]

The Semien warlord Wube Haile Maryam governed not only the western side of the Tekeze river since 1826 but also expanded into the east of the Tekeze river and conquered Tigray and areas of what is now in present-day Eritrea during the 1830s.[11][13][6]

19th and 20th century studies

[edit]Geographical and anthropological evidence from European scholars studying Abyssinia in the 19th and early 20th centuries characterizing Amhara and Tigray as historically separate kingdoms of Abyssinia, differing in language, dress and customs, and separated by the Tekeze River.

Examples includes 1831 publication based on Nathaniel Pearce journals during his residency in early 19th century Abyssinia, that distinguished areas west of Tekeze as separate from Tigray. Other accounts include the 1847 work of traveller Mansfield Parkyns who observed that the areas west of the Tekeze river were the boundary between Tigray and Begemder, which was similarly asserted by his contemporary Walter Plowden in his posthumously published writings in 1868.[6][5]

1944 annexation of Western Tigray into Amhara

[edit]

In 1944, the area was taken from Tigray and given to Gondar administration by Haile Selassie to punish Tigray for the first Woyane rebellion.

The last monarch prince, Raesi Mengesha Seyoum also speaks how when growing up all Western Tigray and Southern Tigray to Alwuha Milash belonged to Tigray. Western Tigray and portions of Southern Tigray was taken from Tigray by Haileslassie in 1948EC and 1949EC (1955 and 1956 GC) and given to his son Algaworash Asfawoson as a gift to expand his administration and punish the Woyane peasant upraising despite the place belonging to Tigray under his father's Raesi Seyoum rule.[14] The same is also testified by the grandson of the then ruler of Wolqait district Raesi Hagos.[15] The grandson of Raesi Araya (Uncle of King Yohannes IV) named Raesi Muuz also speaks the same facts.[16]

During the forceful annexation of Western Tigray – Dergue census shows that Western Tigray remained Tigrayan both in Language and culture.[17] Dergue officially complain about the inhabitants being Tigrayan and these more sympathetic towards TPLF is also recorded in the Dergue documents which are compiled in the evidences are given [citation needed] Recent academic publications shows that the Top-secret internal communication by DERG regarding the population of Welkait and Tsegede (Western Tigray, Ethiopia) dated 04/16/1984 GC states "TPLF has been freely roaming in Welkait and Tsegede weredas for the last five years and the people are Tigrinya speakers, the TPLF has found a fertile ground".[18] A more robust detailed explanation is given here[19]

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia formation and return to Tigray (1991)

[edit]In the early 1990s, parts of Begemder province was annexed into the Tigray Region, after the Tigray People's Liberation Front-led Ethiopian alliance gained control of Ethiopia. The TPLF regime annexed the area for strategic (corridor to the Sudan) and economic (fertile land) reasons.[6][20][21]

On May 23, 1992, the TPLF-led government admitted that there was vehement and widespread opposition from the public against the new administrative map of the regions. However, the government then launch military campaigns in Begemder, engaging in the arbitrary arrests, the killing of civilians (including elderly, women and children), and mass displacement of the population. For the TPLF, the objective was to change the demographic composition of the province.[6] This claim is strongly refuted as the Amhara population did grow in Western Tigray from 1991 to 2020 than ever before as can be shown in Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia 1995[22] and 2007[23] census. It was also described as a smokescreen for ethnic cleansing of Tigrayans by Amhara nationalists[17]

Ethnic cleansing of Tigrayans

[edit]During the Tigray War, Amhara Region militias took control of most parts of the Western Zone in November 2020, which was then occupied for a duration by the joint Ethiopian and Eritrean armies.[20] Human Rights Watch (HRW) described this as "represent[ing] a violent reversal of changes to Ethiopia's contested internal boundaries enacted by the Tigray People's Liberation Front-led Ethiopian federal government in 1992", and after human rights abuses over many years by Tigrayan security against ethnic Amharas and Walqaytes,[a] serving as a backdrop to the eventual violence and expulsion of Tigrayan communities.[24] HRW further noted that the area was part of Begemder, and incorporated into Tigray province, and for decades, the TPLF led government brutally suppressed those who asserted their Amhara identity in the area.[3][25] This claim is strongly refuted as the population Amharic speaking residents grew during this period. After the end of the forceful annexation of Western Tigray by Haile Selassie and Derg regimes, the census in 1994 and 2007 consistently show majority Tigrayan but an increase in percentage of Amhara residents. Tigrinya speakers were the majority in Welkait well before the emergence of the TPLF—which invalidates the assertion that TPLF needed to carry out resettlement to shift the demographics of the area in Tigray's favor—there nonetheless was a resettlement of Tigrayans in what has become Western Tigray after the coming to power of the TPLF led EPRDF coalition. Some of the evidences are given in[17] and.[19] The effect of these resettlement programs was negligible and that some areas in Western Tigray have actually seen an increase in the Amhara population while the number of Tigrayans decreased as can be seen from the census. This is because increased Amhara laborers influx to Welkait as these areas start to demand more manpower for Sesam harvest seasons. Another reason is the relative peace and stability in WelQait and Western Tigray compared to the insecurity and kidnappings in Northern Gonder by bandits locally named Armachiho shifta "የኣርማጭሆ ሽፍታ". Majority of these bandits from Northern Gonder were renamed "Gonder Fano" and are mainly responsible for the ethnic cleansing of Tigrayans as was proved by Human rights watch reports.

On 17 March 2021, the Transitional Government of Tigray’s communication head, Etenesh Nigusse, claimed on VOA Tigrigna that more than 700,000 Tigrayans have been forcibly removed by Amhara forces from the Western Zone Western Tigray, further claiming that the entire population of the Western Zone now stands at around 400 000. Gizachew Muluneh, head of Amhara Regional Communication Affairs, disputed this, arguing that Etenesh's figures were too high.[26] During the occupation, multiple atrocities were committed by Eritrean, Amara and Ethiopian forces.[27]

French researcher Mehdi Labzaé documented the rise of Amhara nationalism since 2015/6 and managed to interview several actors involved in the annexation and ethnic cleansing campaign in Tigray since November 2020. In his article, he lists a series of massacres carried out in Western Tigray after the Amhara region annexed it in November 2020. Mass violence was not his initial research object, but he states, "my investigation of the massacres stems from an exploration of the agrarian grounds for Amhara nationalism." From his research, he concludes that "These accounts show how the successive massacres took place as part of a deliberate policy implemented by the fanno, ASF, and Wolqayt Committee – Prosperity party administration of the Wolqayt-Tegedé-Setit-Humera zone, the with the complicity of Eritrean troops and at least implicit backing of the ENDF. The context, modus operandi and what perpetrators told the victim all converge towards the fact that the intentional targeting of civilians served the purpose of freeing land for occupying Amhara forces. Killing civilians would scare the remaining Tigrayans and make them flee. However, on many occasions, Tigrayans were prevented to leave, as having them in the zone was also a lucrative business for fanno who could regularly ransom them."[28]

Language

[edit]Eike Haberland Map (Published: Wiesbaden : Steiner, 1965) Shows that by 14C Amharic was spoken at Central Ethiopia very far from Western Tigray while Tigrigna was spoken in the North in what is now called Tigray.

Furthermore, the 1994 census report indicates that 96.5% of the inhabitants of western Tigray were ethnically Tigrayans while only 3% were Amhara, which changed to 92.3% and 6.5% respectively in the 2007 census.

Belgian researches analyzed list of 574 place names as recorded by Ellero and his translators was extracted from the notebooks of ethnographer Giovanni Ellero, holding field notes from Welkait in the 1930s. The etymology of almost all place names is of Tigrinya origin, with a few of Oromo, Falasha, Arab, or biblical origin. Less than ten locations that held a name of Amharic origin in 1939 are found in the whole list of place names. Specifically, among the 574 place names, there are 229 "’Addi …" (village in Tigrinya) and 49 "May …" (water).[29]

Demographics

[edit]

Based on the 2007 census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), this zone has a total population of 356,598, of whom 182,571 are men and 174,027 women; 71,823 or 20.14% are urban inhabitants. The two largest ethnic groups reported in the Western Zone were Tigrayan (92.28%) and Amhara (6.48%); all other ethnic groups made up 1.24% of the population. Tigrinya is spoken as a first language by 86.73, and Amharic by 12.18%; the remaining 1.09% spoke all other primary languages reported. A total of 96.25% of the population said they were Orthodox Christians, and 3.68% were Muslim.[23]

At the time of the 1994 national census, the Western Zone included the six woredas that were split off in 2005 to form the new the North Western Zone. That census reported a total population of 733,962, of whom 371,198 were males and 362,764 females; 84,560 or 11.5% of its population were urban dwellers. The inhabitants of the zone were predominantly Tigrayan, at 91.5% of the population, while 4.3% were Amhara, 3.5% foreign residents from Eritrea, and 0.2% Kunama; all other ethnic groups accounted for 0.5% of the population. Tigrinya was spoken as a first language by 94.45% of the inhabitants, and Amharic by 4.85%; the remaining 0.7% spoke all other primary languages reported. 96.28% of the population said they were Orthodox Christians, and 3.51% were Muslim. Concerning education in the Zone, 9.01% of the population were considered literate; 11.34% of children aged 7–12 were in primary school, while 0.65% of the children aged 13–14 were in junior secondary school, and 0.51% of children aged 15–18 were in senior secondary school. Concerning sanitary conditions, about 63% of the urban houses and 18% of all houses had access to safe drinking water at the time of the census; about 19% of the urban and 5% of the total had toilet facilities.[22]

According to a 24 May 2004 World Bank memorandum, 6% of the inhabitants of the Western Zone have access to electricity, and this zone has a road density of 23.3 kilometers per 1000 square kilometers. Rural households have an average of 1 hectare of land (compared to the national average of 1.01 and a regional average of 0.51)[30] and an average 1.3 head of livestock. 19.9% of the population is in non-farm related jobs, compared to the national average of 25% and a regional average of 28%. Of all eligible children, 55% are enrolled in primary school, and 16% in secondary schools. 100% of the zone is exposed to malaria. The memorandum gave this zone a drought risk rating of 533.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Geohive: Ethiopia Archived 2012-08-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Nyssen, Jan (2022-08-18), Western Tigray in 109 historical and 31 ethno-linguistic maps (1607–2014), doi:10.5281/zenodo.7007604, retrieved 2023-04-15

- ^ a b ""We Will Erase You from This Land": Crimes Against Humanity and Ethnic Cleansing in Ethiopia's Western Tigray Zone". Human Rights Watch. 2022-04-06.

- ^ Ullendorff, Edward (1965). The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36, 37.

- ^ a b John, Sonja (2021). "The Potential of Democratization in Ethiopia: The Welkait Question as a Litmus Test". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 56 (5): 1007–1023. doi:10.1177/00219096211007657. S2CID 236898666.

- ^ a b c d e Kendie, Daniel (1994). "Which Way the Horn of Africa: Disintegration or Confederation". Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies. 22 (1–2): 47–53. doi:10.5070/F7221-2016718.

- ^ a b Edwards, David N. (June 2013). "David W. Phillipson. Foundations of an African civilisation: Aksum & the northern Horn 1000 BC–AD 1300. x+294 pages, 94 illustrations. 2012. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer; 978-1-84701-041-4 hardback £ 40". Antiquity. 87 (336): 618–620. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00049309. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 163959093.

- ^ a b Fattovich, Rodolfo; Bard, Kathryn A. (2001). "The Proto-Aksumite Period: An Overview". Annales d'Éthiopie. 17 (1): 3–24. doi:10.3406/ethio.2001.987.

- ^ Russell, Michael (1845). Nubia and Abyssinia: Comprehending their civil history, antiquities, arts, religion, literature, and natural history. Illustr. by a map, and several engravings. Harper.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Chris Prouty (1986). "The background of Taytu Betul Hayle Maryam". Empress Taytu and Menilek II Ethiopia 1883–1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services. pp. 26–43. ISBN 9780932415103.

- ^ a b Akyeampong, Emmanuel Kwaku; Gates, Henry Louis (2012). Dictionary of African biography vol 1-6. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9780195382075.

- ^ Mordechai, Abir (1968). Ethiopia: the Era of the Princes: The Challenge of Islam and Re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. London: Longmans, Green. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780582645172. OCLC 729977710.

- ^ Caulk, Richard (1984). "Bad Men of the Borders: Shum and Shefta in Northern Ethiopia in the 19th Century". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 17 (2). Boston University African Center: 204. doi:10.2307/218604. JSTOR 218604.

- ^ Ras mengesha sium briefly explained on the border of tigray, 25 December 2018, retrieved 2023-04-15

- ^ በአፄ የሃንስ ወልቃይትን ስያስተዳድሩ የነበሩ ራስ ሓጎስ የልጅ ልጅ የሆኑት አቶ ህስቅያስ በላይ ስለትግራይ ግዛቶች ሲናገሩ!, 13 February 2019, retrieved 2023-04-15

- ^ "የትግራይ ወሰን ቆቦን ኣካቶ እስከ አሉሃ ምላሽ ድረስ ነበር። ፈታውራሪ ሙኡዝ በየነ | By Tigray Press ልሳን ትግራይ | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ a b c Nyssen, Jan (2022-11-17). "Amhara nationalist claims over Western Tigray are a smokescreen for ethnic cleansing". Ethiopia Insight. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ Zegeye, Leake; Nyssen, Jan; Asefa, Dereje T. (2022-11-26), "Derg; Tigray; Western Tigray; Welkait", Top-secret internal communication by DERG regarding the population of Welkait and Tsegede (Western Tigray, Ethiopia), 1984, doi:10.5281/zenodo.7366085, retrieved 2023-04-15

- ^ a b Tesfaye, Abel (2022-08-03). "Under Ethiopia's federal system, Western Tigray belongs in Tigray". Ethiopia Insight. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ a b Gebre, Samuel (16 March 2021). "Ethiopia's Amhara Seize Disputed Territory Amid Tigray Conflict". BNN Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Ethiopia aid 'spent on weapons'". 3 March 2010.

- ^ a b The 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Tigray Region Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, vol. 1, part 1: Tables 2.1, 2.11, 2.19, 3.5, 3.7, 6.3, 6.11, 6.13

- ^ a b Census 2007 Tables: Tigray Region Archived 2010-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 3.1, 3.2, 3.4.

- ^ Roth, Kenneth (2022-06-10). "Ethiopia's Invisible Ethnic Cleansing". Foreign Affairs. ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- ^ "Inside Humera, a town scarred by Ethiopia's war". Reuters. 2020-11-23. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Atsbeha, Mulugeta (17 March 2021). "ቢሮ ኮሚኒኼሽን ክልል ትግራይ 700 ሽሕ ነበርቲ ካብ ም/ትግራይ ተመዛቢሎም ይብል መንግስቲ ክልል ኣምሓራ ግን ነዚ ይነጽግ" [The Tigray Regional Communication Bureau says 700,000 residents have been displaced from the state, but the Amhara Regional State government denies this]. Voice of America (in Tigrinya).

- ^ "At least 30 bodies float down river between Ethiopia's Tigray and Sudan". CNN. 4 August 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Labzaé, Mehdi (7 June 2024). "The Ethnic Cleansing Policy in Western Tigray since November 2020 : Establishing the Facts and Understanding the Logic », , , p. . DOI : 10.3917/polaf.173.0137. URL". Politique Africaine. 173 (2024/1 (n° 173)): 137–162. doi:10.3917/polaf.173.0137 – via cairn.info.

- ^ Nyssen, Jan (2022). "List of place names in Welkait (Tigray, Ethiopia), as recorded in 1939". Aethiopica. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7066265. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Comparative national and regional figures from the World Bank publication, Klaus Deininger et al. "Tenure Security and Land Related Investment", WP-2991 (accessed 23 March 2006).

- ^ World Bank, Four Ethiopias: A Regional Characterization (accessed 23 March 2006).

Further reading

[edit]- Nyssen, Jan (22 July 2023). "Western Tigray in 165 historical and 33 ethno-linguistic maps (1475–2014)". Department of Geography. Ghent University. Version 7.1. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6554937.