Obesity

| Obesity | |

|---|---|

| |

| Silhouettes and waist circumferences representing optimal, overweight, and obese | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Increased fat[1] |

| Complications | Cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, certain types of cancer, osteoarthritis, depression[2][3] |

| Causes | Excessive consumption of energy-dense foods, sedentary work and lifestyles and lack of physical activity, changes in modes of transportation, urbanization, lack of supportive policies, lack of access to a healthy diet, genetics[1][4] |

| Diagnostic method | BMI > 30 kg/m2[1] |

| Prevention | Societal changes, changes in the food industry, access to a healthy lifestyle, personal choices[1] |

| Treatment | Diet, exercise, medications, surgery[5][6] |

| Prognosis | Reduced life expectancy[2] |

| Frequency | Over 1 billion / 12.5% (2022)[7] |

| Deaths | 2.8 million people per year |

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease,[8][9][10] in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it can potentially have negative effects on health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's weight divided by the square of the person's height—is over 30 kg/m2; the range 25–30 kg/m2 is defined as overweight.[1] Some East Asian countries use lower values to calculate obesity.[11] Obesity is a major cause of disability and is correlated with various diseases and conditions, particularly cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, certain types of cancer, and osteoarthritis.[2][12][13]

Obesity has individual, socioeconomic, and environmental causes. Some known causes are diet, physical activity, automation, urbanization, genetic susceptibility, medications, mental disorders, economic policies, endocrine disorders, and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals.[1][4][14][15]

While a majority of obese individuals at any given time attempt to lose weight and are often successful, maintaining weight loss long-term is rare.[16] There is no effective, well-defined, evidence-based intervention for preventing obesity. Obesity prevention requires a complex approach, including interventions at societal, community, family, and individual levels.[1][13] Changes to diet as well as exercising are the main treatments recommended by health professionals.[2] Diet quality can be improved by reducing the consumption of energy-dense foods, such as those high in fat or sugars, and by increasing the intake of dietary fiber, if these dietary choices are available, affordable, and accessible.[1] Medications can be used, along with a suitable diet, to reduce appetite or decrease fat absorption.[5] If diet, exercise, and medication are not effective, a gastric balloon or surgery may be performed to reduce stomach volume or length of the intestines, leading to feeling full earlier, or a reduced ability to absorb nutrients from food.[6][17]

Obesity is a leading preventable cause of death worldwide, with increasing rates in adults and children.[18] In 2022, over 1 billion people were obese worldwide (879 million adults and 159 million children), representing more than a double of adult cases (and four times higher than cases among children) registered in 1990.[7][19] Obesity is more common in women than in men.[1] Today, obesity is stigmatized in most of the world. Conversely, some cultures, past and present, have a favorable view of obesity, seeing it as a symbol of wealth and fertility.[2][20] The World Health Organization, the US, Canada, Japan, Portugal, Germany, the European Parliament and medical societies, e.g. the American Medical Association, classify obesity as a disease. Others, such as the UK, do not.[21][22][23][24]

Classification

| Category[25] | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.5 |

| Normal weight | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| Overweight | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| Obese (class I) | 30.0 – 34.9 |

| Obese (class II) | 35.0 – 39.9 |

| Obese (class III) | ≥ 40.0 |

Obesity is typically defined as a substantial accumulation of body fat that could impact health.[26] Medical organizations tend to classify people as obese based on body mass index (BMI) – a ratio of a person's weight in kilograms to the square of their height in meters. For adults, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines "overweight" as a BMI 25 or higher, and "obese" as a BMI 30 or higher.[26] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) further subdivides obesity based on BMI, with a BMI 30 to 35 called class 1 obesity; 35 to 40, class 2 obesity; and 40+, class 3 obesity.[27]

For children, obesity measures take age into consideration along with height and weight. For children aged 5–19, the WHO defines obesity as a BMI two standard deviations above the median for their age (a BMI around 18 for a five-year old; around 30 for a 19-year old).[26][28] For children under five, the WHO defines obesity as a weight three standard deviations above the median for their height.[26]

Some modifications to the WHO definitions have been made by particular organizations.[29] The surgical literature breaks down class II and III or only class III obesity into further categories whose exact values are still disputed.[30]

- Any BMI ≥ 35 or 40 kg/m2 is severe obesity.

- A BMI of ≥ 35 kg/m2 and experiencing obesity-related health conditions or ≥ 40 or 45 kg/m2 is morbid obesity.

- A BMI of ≥ 45 or 50 kg/m2 is super obesity.

As Asian populations develop negative health consequences at a lower BMI than Caucasians, some nations have redefined obesity; Japan has defined obesity as any BMI greater than 25 kg/m2[11] while China uses a BMI of greater than 28 kg/m2.[29]

The preferred obesity metric in scholarly circles is the body fat percentage (BF%) – the ratio of the total weight of person's fat to his or her body weight, and BMI is viewed merely as a way to approximate BF%.[31] According to American Society of Bariatric Physicians, levels in excess of 32% for women and 25% for men are generally considered to indicate obesity.[32]

BMI ignores variations between individuals in amounts of lean body mass, particularly muscle mass. Individuals involved in heavy physical labor or sports may have high BMI values despite having little fat. For example, more than half of all NFL players are classified as "obese" (BMI ≥ 30), and 1 in 4 are classified as "extremely obese" (BMI ≥ 35), according to the BMI metric.[33] However, their mean body fat percentage, 14%, is well within what is considered a healthy range.[34] Similarly, Sumo wrestlers may be categorized by BMI as "severely obese" or "very severely obese" but many Sumo wrestlers are not categorized as obese when body fat percentage is used instead (having <25% body fat).[35] Some Sumo wrestlers were found to have no more body fat than a non-Sumo comparison group, with high BMI values resulting from their high amounts of lean body mass.[35]

Effects on health

Obesity increases a person's risk of developing various metabolic diseases, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, Alzheimer disease, depression, and certain types of cancer.[36] Depending on the degree of obesity and the presence of comorbid disorders, obesity is associated with an estimated 2–20 year shorter life expectancy.[37][36] High BMI is a marker of risk for, but not a direct cause of, diseases caused by diet and physical activity.[13]

Mortality

Obesity is one of the leading preventable causes of death worldwide.[38][39][40] The mortality risk is lowest at a BMI of 20–25 kg/m2[41][37][42] in non-smokers and at 24–27 kg/m2 in current smokers, with risk increasing along with changes in either direction.[43][44] This appears to apply in at least four continents.[42] Other research suggests that the association of BMI and waist circumference with mortality is U- or J-shaped, while the association between waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio with mortality is more positive.[45] In Asians the risk of negative health effects begins to increase between 22 and 25 kg/m2.[46] In 2021, the World Health Organization estimated that obesity caused at least 2.8 million deaths annually.[47] On average, obesity reduces life expectancy by six to seven years,[2][48] a BMI of 30–35 kg/m2 reduces life expectancy by two to four years,[37] while severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) reduces life expectancy by ten years.[37]

Morbidity

Obesity increases the risk of many physical and mental conditions. These comorbidities are most commonly shown in metabolic syndrome,[2] a combination of medical disorders which includes: diabetes mellitus type 2, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, and high triglyceride levels.[49] A study from the RAK Hospital found that obese people are at a greater risk of developing long COVID.[50] The CDC has found that obesity is the single strongest risk factor for severe COVID-19 illness.[51]

Complications are either directly caused by obesity or indirectly related through mechanisms sharing a common cause such as a poor diet or a sedentary lifestyle. The strength of the link between obesity and specific conditions varies. One of the strongest is the link with type 2 diabetes. Excess body fat underlies 64% of cases of diabetes in men and 77% of cases in women.[52]: 9

Health consequences fall into two broad categories: those attributable to the effects of increased fat mass (such as osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, social stigmatization) and those due to the increased number of fat cells (diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease).[2][53] Increases in body fat alter the body's response to insulin, potentially leading to insulin resistance. Increased fat also creates a proinflammatory state,[54][55] and a prothrombotic state.[53][56]

Parts of this article (those related to table below) need to be updated. (March 2022) |

| Medical field | Condition | Medical field | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | Dermatology | ||

| Endocrinology and reproductive medicine | Gastroenterology | ||

| Neurology | Oncology[70] | ||

| Psychiatry |

|

Respirology |

|

| Rheumatology and orthopedics |

|

Urology and Nephrology |

Metrics of health

Newer research has focused on methods of identifying healthier obese people by clinicians, and not treating obese people as a monolithic group.[81] Obese people who do not experience medical complications from their obesity are sometimes called (metabolically) healthy obese, but the extent to which this group exists (especially among older people) is in dispute.[82] The number of people considered metabolically healthy depends on the definition used, and there is no universally accepted definition.[83] There are numerous obese people who have relatively few metabolic abnormalities, and a minority of obese people have no medical complications.[83] The guidelines of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists call for physicians to use risk stratification with obese patients when considering how to assess their risk of developing type 2 diabetes.[84]: 59–60

In 2014, the BioSHaRE–EU Healthy Obese Project (sponsored by Maelstrom Research, a team under the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre) came up with two definitions for healthy obesity, one more strict and one less so:[82][85]

| Less strict | More strict | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure measured as follows, with no pharmaceutical help | ||

| Overall (mmHg) | ≤ 140 | ≤ 130 |

| Systolic (mmHg) | N/A | ≤ 85[clarification needed] |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | ≤ 90 | N/A |

| Blood sugar level measured as follows, with no pharmaceutical help | ||

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | ≤ 7.0 | ≤ 6.1 |

| Triglycerides measured as follows, with no pharmaceutical help | ||

| Fasting (mmol/L) | ≤ 1.7 | |

| Non-fasting (mmol/L) | ≤ 2.1 | |

| High-density lipoprotein measured as follows, with no pharmaceutical help | ||

| Men (mmol/L) | > 1.03 | |

| Women (mmol/L) | > 1.3 | |

| No diagnosis of any cardiovascular disease | ||

To come up with these criteria, BioSHaRE controlled for age and tobacco use, researching how both may effect the metabolic syndrome associated with obesity, but not found to exist in the metabolically healthy obese.[86] Other definitions of metabolically healthy obesity exist, including ones based on waist circumference rather than BMI, which is unreliable in certain individuals.[83]

Another identification metric for health in obese people is calf strength, which is positively correlated with physical fitness in obese people.[87] Body composition in general is hypothesized to help explain the existence of metabolically healthy obesity—the metabolically healthy obese are often found to have low amounts of ectopic fat (fat stored in tissues other than adipose tissue) despite having overall fat mass equivalent in weight to obese people with metabolic syndrome.[88]: 1282

Survival paradox

Although the negative health consequences of obesity in the general population are well supported by the available research evidence, health outcomes in certain subgroups seem to be improved at an increased BMI, a phenomenon known as the obesity survival paradox.[89] The paradox was first described in 1999 in overweight and obese people undergoing hemodialysis[89] and has subsequently been found in those with heart failure and peripheral artery disease (PAD).[90]

In people with heart failure, those with a BMI between 30.0 and 34.9 had lower mortality than those with a normal weight. This has been attributed to the fact that people often lose weight as they become progressively more ill.[91] Similar findings have been made in other types of heart disease. People with class I obesity and heart disease do not have greater rates of further heart problems than people of normal weight who also have heart disease. In people with greater degrees of obesity, however, the risk of further cardiovascular events is increased.[92][93] Even after cardiac bypass surgery, no increase in mortality is seen in the overweight and obese.[94] One study found that the improved survival could be explained by the more aggressive treatment obese people receive after a cardiac event.[95] Another study found that if one takes into account chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in those with PAD, the benefit of obesity no longer exists.[90]

Causes

The "a calorie is a calorie" model of obesity posits a combination of excessive food energy intake and a lack of physical activity as the cause of most cases of obesity.[96] A limited number of cases are due primarily to genetics, medical reasons, or psychiatric illness.[15] In contrast, increasing rates of obesity at a societal level are felt to be due to an easily accessible and palatable diet,[97] increased reliance on cars, and mechanized manufacturing.[98][99]

Some other factors have been proposed as causes towards rising rates of obesity worldwide, including insufficient sleep, endocrine disruptors, increased usage of certain medications (such as atypical antipsychotics),[100] increases in ambient temperature, decreased rates of smoking,[101] demographic changes, increasing maternal age of first-time mothers, changes to epigenetic dysregulation from the environment, increased phenotypic variance via assortative mating, social pressure to diet,[102] among others. According to one study, factors like these may play as big of a role as excessive food energy intake and a lack of physical activity;[103] however, the relative magnitudes of the effects of any proposed cause of obesity is varied and uncertain, as there is a general need for randomized controlled trials on humans before definitive statement can be made.[104]

According to the Endocrine Society, there is "growing evidence suggesting that obesity is a disorder of the energy homeostasis system, rather than simply arising from the passive accumulation of excess weight".[105]

Diet

|

No data

<1,600 (<6,700)

1,600–1,800 (6,700–7,500)

1,800–2,000 (7,500–8,400)

2,000–2,200 (8,400–9,200)

2,200–2,400 (9,200–10,000)

2,400–2,600 (10,000–10,900)

|

2,600–2,800 (10,900–11,700)

2,800–3,000 (11,700–12,600)

3,000–3,200 (12,600–13,400)

3,200–3,400 (13,400–14,200)

3,400–3,600 (14,200–15,100)

>3,600 (>15,100)

|

Excess appetite for palatable, high-calorie food (especially fat, sugar, and certain animal proteins) is seen as the primary factor driving obesity worldwide, likely because of imbalances in neurotransmitters affecting the drive to eat.[107] Dietary energy supply per capita varies markedly between different regions and countries. It has also changed significantly over time.[106] From the early 1970s to the late 1990s the average food energy available per person per day (the amount of food bought) increased in all parts of the world except Eastern Europe. The United States had the highest availability with 3,654 calories (15,290 kJ) per person in 1996.[106] This increased further in 2003 to 3,754 calories (15,710 kJ).[106] During the late 1990s, Europeans had 3,394 calories (14,200 kJ) per person, in the developing areas of Asia there were 2,648 calories (11,080 kJ) per person, and in sub-Saharan Africa people had 2,176 calories (9,100 kJ) per person.[106][108] Total food energy consumption has been found to be related to obesity.[109]

The widespread availability of dietary guidelines[110] has done little to address the problems of overeating and poor dietary choice.[111] From 1971 to 2000, obesity rates in the United States increased from 14.5% to 30.9%.[112] During the same period, an increase occurred in the average amount of food energy consumed. For women, the average increase was 335 calories (1,400 kJ) per day (1,542 calories (6,450 kJ) in 1971 and 1,877 calories (7,850 kJ) in 2004), while for men the average increase was 168 calories (700 kJ) per day (2,450 calories (10,300 kJ) in 1971 and 2,618 calories (10,950 kJ) in 2004). Most of this extra food energy came from an increase in carbohydrate consumption rather than fat consumption.[113] The primary sources of these extra carbohydrates are sweetened beverages, which now account for almost 25 percent of daily food energy in young adults in America,[114] and potato chips.[115] Consumption of sweetened beverages such as soft drinks, fruit drinks, and iced tea is believed to be contributing to the rising rates of obesity[116][117] and to an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.[118] Vitamin D deficiency is related to diseases associated with obesity.[119]

As societies become increasingly reliant on energy-dense, big-portions, and fast-food meals, the association between fast-food consumption and obesity becomes more concerning.[120] In the United States, consumption of fast-food meals tripled and food energy intake from these meals quadrupled between 1977 and 1995.[121]

Agricultural policy and techniques in the United States and Europe have led to lower food prices. In the United States, subsidization of corn, soy, wheat, and rice through the U.S. farm bill has made the main sources of processed food cheap compared to fruits and vegetables.[122] Calorie count laws and nutrition facts labels attempt to steer people toward making healthier food choices, including awareness of how much food energy is being consumed.

Obese people consistently under-report their food consumption as compared to people of normal weight.[123] This is supported both by tests of people carried out in a calorimeter room[124] and by direct observation.

Sedentary lifestyle

A sedentary lifestyle may play a significant role in obesity.[52]: 10 Worldwide there has been a large shift towards less physically demanding work,[125][126][127] and currently at least 30% of the world's population gets insufficient exercise.[126] This is primarily due to increasing use of mechanized transportation and a greater prevalence of labor-saving technology in the home.[125][126][127] In children, there appear to be declines in levels of physical activity (with particularly strong declines in the amount of walking and physical education), likely due to safety concerns, changes in social interaction (such as fewer relationships with neighborhood children), and inadequate urban design (such as too few public spaces for safe physical activity).[128] World trends in active leisure time physical activity are less clear. The World Health Organization indicates people worldwide are taking up less active recreational pursuits, while research from Finland[129] found an increase and research from the United States found leisure-time physical activity has not changed significantly.[130] Physical activity in children may not be a significant contributor.[131]

In both children and adults, there is an association between television viewing time and the risk of obesity.[132][133][134] Increased media exposure increases the rate of childhood obesity, with rates increasing proportionally to time spent watching television.[135]

Genetics

This section needs to be updated. (July 2021) |

Like many other medical conditions, obesity is the result of an interplay between genetic and environmental factors.[137] Polymorphisms in various genes controlling appetite and metabolism predispose to obesity when sufficient food energy is present. As of 2006, more than 41 of these sites on the human genome have been linked to the development of obesity when a favorable environment is present.[138] People with two copies of the FTO gene (fat mass and obesity associated gene) have been found on average to weigh 3–4 kg more and have a 1.67-fold greater risk of obesity compared with those without the risk allele.[139] The differences in BMI between people that are due to genetics varies depending on the population examined from 6% to 85%.[140]

Obesity is a major feature in several syndromes, such as Prader–Willi syndrome, Bardet–Biedl syndrome, Cohen syndrome, and MOMO syndrome. (The term "non-syndromic obesity" is sometimes used to exclude these conditions.)[141] In people with early-onset severe obesity (defined by an onset before 10 years of age and body mass index over three standard deviations above normal), 7% harbor a single point DNA mutation.[142]

Studies that have focused on inheritance patterns rather than on specific genes have found that 80% of the offspring of two obese parents were also obese, in contrast to less than 10% of the offspring of two parents who were of normal weight.[143] Different people exposed to the same environment have different risks of obesity due to their underlying genetics.[144]

The thrifty gene hypothesis postulates that, due to dietary scarcity during human evolution, people are prone to obesity. Their ability to take advantage of rare periods of abundance by storing energy as fat would be advantageous during times of varying food availability, and individuals with greater adipose reserves would be more likely to survive famine. This tendency to store fat, however, would be maladaptive in societies with stable food supplies.[medical citation needed] This theory has received various criticisms, and other evolutionarily-based theories such as the drifty gene hypothesis and the thrifty phenotype hypothesis have also been proposed.[medical citation needed]

Other illnesses

Certain physical and mental illnesses and the pharmaceutical substances used to treat them can increase risk of obesity. Medical illnesses that increase obesity risk include several rare genetic syndromes (listed above) as well as some congenital or acquired conditions: hypothyroidism, Cushing's syndrome, growth hormone deficiency,[145] and some eating disorders such as binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome.[2] However, obesity is not regarded as a psychiatric disorder, and therefore is not listed in the DSM-IVR as a psychiatric illness.[146] The risk of overweight and obesity is higher in patients with psychiatric disorders than in persons without psychiatric disorders.[147] Obesity and depression influence each other mutually, with obesity increasing the risk of clinical depression, and also depression leading to a higher chance of developing obesity.[3]

Drug-induced obesity

Certain medications may cause weight gain or changes in body composition; these include insulin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, steroids, certain anticonvulsants (phenytoin and valproate), pizotifen, and some forms of hormonal contraception.[2]

Social determinants

While genetic influences are important to understanding obesity, they cannot completely explain the dramatic increase seen within specific countries or globally.[148][better source needed] Though it is accepted that energy consumption in excess of energy expenditure leads to increases in body weight on an individual basis, the cause of the shifts in these two factors on the societal scale is much debated. There are a number of theories as to the cause but most believe it is a combination of various factors.

The correlation between social class and BMI varies globally. Research in 1989 found that in developed countries women of a high social class were less likely to be obese. No significant differences were seen among men of different social classes. In the developing world, women, men, and children from high social classes had greater rates of obesity.[better source needed][149] In 2007 repeating the same research found the same relationships, but they were weaker. The decrease in strength of correlation was felt to be due to the effects of globalization.[150] Among developed countries, levels of adult obesity, and percentage of teenage children who are overweight, are correlated with income inequality. A similar relationship is seen among US states: more adults, even in higher social classes, are obese in more unequal states.[151]

Many explanations have been put forth for associations between BMI and social class. It is thought that in developed countries, the wealthy are able to afford more nutritious food, they are under greater social pressure to remain slim, and have more opportunities along with greater expectations for physical fitness. In undeveloped countries the ability to afford food, high energy expenditure with physical labor, and cultural values favoring a larger body size are believed to contribute to the observed patterns.[150] Attitudes toward body weight held by people in one's life may also play a role in obesity. A correlation in BMI changes over time has been found among friends, siblings, and spouses.[152] Stress and perceived low social status appear to increase risk of obesity.[151][153][154]

Smoking has a significant effect on an individual's weight. Those who quit smoking gain an average of 4.4 kilograms (9.7 lb) for men and 5.0 kilograms (11.0 lb) for women over ten years.[155] However, changing rates of smoking have had little effect on the overall rates of obesity.[156]

In the United States, the number of children a person has is related to their risk of obesity. A woman's risk increases by 7% per child, while a man's risk increases by 4% per child.[157] This could be partly explained by the fact that having dependent children decreases physical activity in Western parents.[158]

In the developing world urbanization is playing a role in increasing rate of obesity. In China overall rates of obesity are below 5%; however, in some cities rates of obesity are greater than 20%.[159] In part, this may be because of urban design issues (such as inadequate public spaces for physical activity).[128] Time spent in motor vehicles, as opposed to active transportation options such as cycling or walking, is correlated with increased risk of obesity.[160][161]

Malnutrition in early life is believed to play a role in the rising rates of obesity in the developing world.[162] Endocrine changes that occur during periods of malnutrition may promote the storage of fat once more food energy becomes available.[162]

Gut bacteria

The study of the effect of infectious agents on metabolism is still in its early stages. Gut flora has been shown to differ between lean and obese people. There is an indication that gut flora can affect the metabolic potential. This apparent alteration is believed to confer a greater capacity to harvest energy contributing to obesity. Whether these differences are the direct cause or the result of obesity has yet to be determined unequivocally.[163] The use of antibiotics among children has also been associated with obesity later in life.[164][165]

An association between viruses and obesity has been found in humans and several different animal species. The amount that these associations may have contributed to the rising rate of obesity is yet to be determined.[166]

Other factors

Not getting enough sleep is also associated with obesity.[167][168] Whether one causes the other is unclear.[167] Even if short sleep does increase weight gain, it is unclear if this is to a meaningful degree or if increasing sleep would be of benefit.[169]

Some have proposed that chemical compounds called "obesogens" may play a role in obesity.

Certain aspects of personality are associated with being obese.[170] Loneliness,[171] neuroticism, impulsivity, and sensitivity to reward are more common in people who are obese while conscientiousness and self-control are less common in people who are obese.[170][172] Because most of the studies on this topic are questionnaire-based, it is possible that these findings overestimate the relationships between personality and obesity: people who are obese might be aware of the social stigma of obesity and their questionnaire responses might be biased accordingly.[170] Similarly, the personalities of people who are obese as children might be influenced by obesity stigma, rather than these personality factors acting as risk factors for obesity.[170]

In relation to globalization, it is known that trade liberalization is linked to obesity; research, based on data from 175 countries during 1975–2016, showed that obesity prevalence was positively correlated with trade openness, and the correlation was stronger in developing countries.[173]

Pathophysiology

Two distinct but related processes are considered to be involved in the development of obesity: sustained positive energy balance (energy intake exceeding energy expenditure) and the resetting of the body weight "set point" at an increased value.[105] The second process explains why finding effective obesity treatments has been difficult. While the underlying biology of this process still remains uncertain, research is beginning to clarify the mechanisms.[105]

At a biological level, there are many possible pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development and maintenance of obesity.[174] This field of research had been almost unapproached until the leptin gene was discovered in 1994 by J. M. Friedman's laboratory.[175] While leptin and ghrelin are produced peripherally, they control appetite through their actions on the central nervous system. In particular, they and other appetite-related hormones act on the hypothalamus, a region of the brain central to the regulation of food intake and energy expenditure. There are several circuits within the hypothalamus that contribute to its role in integrating appetite, the melanocortin pathway being the most well understood.[174] The circuit begins with an area of the hypothalamus, the arcuate nucleus, that has outputs to the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), the brain's feeding and satiety centers, respectively.[176]

The arcuate nucleus contains two distinct groups of neurons.[174] The first group coexpresses neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and has stimulatory inputs to the LH and inhibitory inputs to the VMH. The second group coexpresses pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) and has stimulatory inputs to the VMH and inhibitory inputs to the LH. Consequently, NPY/AgRP neurons stimulate feeding and inhibit satiety, while POMC/CART neurons stimulate satiety and inhibit feeding. Both groups of arcuate nucleus neurons are regulated in part by leptin. Leptin inhibits the NPY/AgRP group while stimulating the POMC/CART group. Thus a deficiency in leptin signaling, either via leptin deficiency or leptin resistance, leads to overfeeding and may account for some genetic and acquired forms of obesity.[174]

Management

The main treatment for obesity consists of weight loss via lifestyle interventions, including prescribed diets and physical exercise.[22][96][177][178] Although it is unclear what diets might support long-term weight loss, and although the effectiveness of low-calorie diets is debated,[179] lifestyle changes that reduce calorie consumption or increase physical exercise over the long term also tend to produce some sustained weight loss, despite slow weight regain over time.[22][179][180][181]

Although 87% of participants in the National Weight Control Registry were able to maintain 10% body weight loss for 10 years,[182][clarification needed] the most appropriate dietary approach for long term weight loss maintenance is still unknown.[183] In the US, intensive behavioral interventions combining both dietary changes and exercise are recommended.[22][177][184] Intermittent fasting has no additional benefit of weight loss compared to continuous energy restriction.[183] Adherence is a more important factor in weight loss success than whatever kind of diet an individual undertakes.[183][185]

Several hypo-caloric diets are effective.[22] In the short-term low carbohydrate diets appear better than low fat diets for weight loss.[186] In the long term, however, all types of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets appear equally beneficial.[186][187] Heart disease and diabetes risks associated with different diets appear to be similar.[188]

Promotion of the Mediterranean diets among the obese may lower the risk of heart disease.[186] Decreased intake of sweet drinks is also related to weight-loss.[186] Success rates of long-term weight loss maintenance with lifestyle changes are low, ranging from 2–20%.[189] Dietary and lifestyle changes are effective in limiting excessive weight gain in pregnancy and improve outcomes for both the mother and the child.[190] Intensive behavioral counseling is recommended in those who are both obese and have other risk factors for heart disease.[191]

Health policy

Obesity is a complex public health and policy problem because of its prevalence, costs, and health effects.[192] As such, managing it requires changes in the wider societal context and effort by communities, local authorities, and governments.[184] Public health efforts seek to understand and correct the environmental factors responsible for the increasing prevalence of obesity in the population. Solutions look at changing the factors that cause excess food energy consumption and inhibit physical activity. Efforts include federally reimbursed meal programs in schools, limiting direct junk food marketing to children,[193] and decreasing access to sugar-sweetened beverages in schools.[194] The World Health Organization recommends the taxing of sugary drinks.[195] When constructing urban environments, efforts have been made to increase access to parks and to develop pedestrian routes.[196]

Mass media campaigns seem to have limited effectiveness in changing behaviors that influence obesity, but may increase knowledge and awareness regarding physical activity and diet, which might lead to changes in the long term. Campaigns might also be able to reduce the amount of time spent sitting or lying down and positively affect the intention to be active physically.[197][198] Nutritional labelling with energy information on menus might be able to help reducing energy intake while dining in restaurants.[199] Some call for policy against ultra-processed foods.[200][201]

Medical interventions

Medication

Since the introduction of medicines for the management of obesity in the 1930s, many compounds have been tried. Most of them reduce body weight by small amounts, and several of them are no longer marketed for obesity because of their side effects. Out of 25 anti-obesity medications withdrawn from the market between 1964 and 2009, 23 acted by altering the functions of chemical neurotransmitters in the brain. The most common side effects of these drugs that led to withdrawals were mental disturbances, cardiac side effects, and drug abuse or drug dependence. Deaths were reportedly associated with seven products.[202]

Five medications beneficial for long-term use are: orlistat, lorcaserin, liraglutide, phentermine–topiramate, and naltrexone–bupropion.[203] They result in weight loss after one year ranged from 3.0 to 6.7 kg (6.6-14.8 lbs) over placebo.[203] Orlistat, liraglutide, and naltrexone–bupropion are available in both the United States and Europe, phentermine–topiramate is available only in the United States.[204] European regulatory authorities rejected lorcaserin and phentermine-topiramate, in part because of associations of heart valve problems with lorcaserin and more general heart and blood vessel problems with phentermine–topiramate.[204] Lorcaserin was available in the United States and then removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer.[205] Orlistat use is associated with high rates of gastrointestinal side effects[206] and concerns have been raised about negative effects on the kidneys.[207] There is no information on how these drugs affect longer-term complications of obesity such as cardiovascular disease or death;[5] however, liraglutide, when used for type 2 diabetes, does reduce cardiovascular events.[208]

In 2019 a systematic review compared the effects on weight of various doses of fluoxetine (60 mg/d, 40 mg/d, 20 mg/d, 10 mg/d) in obese adults.[209] When compared to placebo, all dosages of fluoxetine appeared to contribute to weight loss but lead to increased risk of experiencing side effects such as dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, insomnia and nausea during period of treatment. However, these conclusions were from low certainty evidence.[209] When comparing, in the same review, the effects of fluoxetine on weight of obese adults, to other anti-obesity agents, omega-3 gel and not receiving a treatment, the authors could not reach conclusive results due to poor quality of evidence.[209]

Among antipsychotic drugs for treating schizophrenia clozapine is the most effective, but it also has the highest risk of causing the metabolic syndrome, of which obesity is the main feature. For people who gain weight because of clozapine, taking metformin may reportedly improve three of the five components of the metabolic syndrome: waist circumference, fasting glucose, and fasting triglycerides.[210]

Surgery

The most effective treatment for obesity is bariatric surgery.[6][22] The types of procedures include laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, vertical-sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion.[203] Surgery for severe obesity is associated with long-term weight loss, improvement in obesity-related conditions,[211] and decreased overall mortality; however, improved metabolic health results from the weight loss, not the surgery.[212] One study found a weight loss of between 14% and 25% (depending on the type of procedure performed) at 10 years, and a 29% reduction in all cause mortality when compared to standard weight loss measures.[213] Complications occur in about 17% of cases and reoperation is needed in 7% of cases.[211]

Epidemiology

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit source data.

In earlier historical periods obesity was rare and achievable only by a small elite, although already recognised as a problem for health. But as prosperity increased in the Early Modern period, it affected increasingly larger groups of the population.[214] Prior to the 1970s, obesity was a relatively rare condition even in the wealthiest of nations, and when it did exist it tended to occur among the wealthy. Then, a confluence of events started to change the human condition. The average BMI of populations in first-world countries started to increase, and consequently there was a rapid increase in the proportion of people overweight and obese.[215]

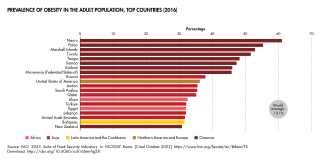

In 1997, the WHO formally recognized obesity as a global epidemic.[114] As of 2008, the WHO estimates that at least 500 million adults (greater than 10%) are obese, with higher rates among women than men.[216] The global prevalence of obesity more than doubled between 1980 and 2014. In 2014, more than 600 million adults were obese, equal to about 13 percent of the world's adult population,[217] with that figure growing to 16% by 2022, according to the World Health Organisation [218] The percentage of adults affected in the United States as of 2015–2016 is about 39.6% overall (37.9% of males and 41.1% of females).[219] In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that overweight and obesity were replacing more traditional public health concerns such as undernutrition and infectious diseases as one of the most significant cause of poor health.[220]

The rate of obesity also increases with age at least up to 50 or 60 years old[52]: 5 and severe obesity in the United States, Australia, and Canada is increasing faster than the overall rate of obesity.[30][221][222] The OECD has projected an increase in obesity rates until at least 2030, especially in the United States, Mexico and England with rates reaching 47%, 39% and 35%, respectively.[223]

Once considered a problem only of high-income countries, obesity rates are rising worldwide and affecting both the developed and developing world.[224] These increases have been felt most dramatically in urban settings.[216]

Sex- and gender-based differences also influence the prevalence of obesity. Globally there are more obese women than men, but the numbers differ depending on how obesity is measured.[225][226]

History

Etymology

Obesity is from the Latin obesitas, which means "stout, fat, or plump". Ēsus is the past participle of edere (to eat), with ob (over) added to it.[227] The Oxford English Dictionary documents its first usage in 1611 by Randle Cotgrave.[228]

Historical attitudes

Ancient Greek medicine recognizes obesity as a medical disorder and records that the Ancient Egyptians saw it in the same way.[214] Hippocrates wrote that "Corpulence is not only a disease itself, but the harbinger of others".[2] The Indian surgeon Sushruta (6th century BCE) related obesity to diabetes and heart disorders.[230] He recommended physical work to help cure it and its side effects.[230] For most of human history, mankind struggled with food scarcity.[231] Obesity has thus historically been viewed as a sign of wealth and prosperity. It was common among high officials in Ancient East Asian civilizations.[232] In the 17th century, English medical author Tobias Venner is credited with being one of the first to refer to the term as a societal disease in a published English language book.[214][233]

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution, it was realized that the military and economic might of nations were dependent on both the body size and strength of their soldiers and workers.[114] Increasing the average body mass index from what is now considered underweight to what is now the normal range played a significant role in the development of industrialized societies.[114] Height and weight thus both increased through the 19th century in the developed world. During the 20th century, as populations reached their genetic potential for height, weight began increasing much more than height, resulting in obesity.[114] In the 1950s, increasing wealth in the developed world decreased child mortality, but as body weight increased, heart and kidney disease became more common.[114][234] During this time period, insurance companies realized the connection between weight and life expectancy and increased premiums for the obese.[2]

Many cultures throughout history have viewed obesity as the result of a character flaw. The obesus or fat character in Ancient Greek comedy was a glutton and figure of mockery. During Christian times, food was viewed as a gateway to the sins of sloth and lust.[20] In modern Western culture, excess weight is often regarded as unattractive, and obesity is commonly associated with various negative stereotypes. People of all ages can face social stigmatization and may be targeted by bullies or shunned by their peers.[235]

Public perceptions in Western society regarding healthy body weight differ from those regarding the weight that is considered ideal – and both have changed since the beginning of the 20th century. The weight that is viewed as an ideal has become lower since the 1920s. This is illustrated by the fact that the average height of Miss America pageant winners increased by 2% from 1922 to 1999, while their average weight decreased by 12%.[236] On the other hand, people's views concerning healthy weight have changed in the opposite direction. In Britain, the weight at which people considered themselves to be overweight was significantly higher in 2007 than in 1999.[237] These changes are believed to be due to increasing rates of adiposity leading to increased acceptance of extra body fat as being normal.[237]

Obesity is still seen as a sign of wealth and well-being in many parts of Africa. This has become particularly common since the HIV epidemic began.[2]

The arts

The first sculptural representations of the human body 20,000–35,000 years ago depict obese females. Some attribute the Venus figurines to the tendency to emphasize fertility while others feel they represent "fatness" in the people of the time.[20] Corpulence is, however, absent in both Greek and Roman art, probably in keeping with their ideals regarding moderation. This continued through much of Christian European history, with only those of low socioeconomic status being depicted as obese.[20]

During the Renaissance some of the upper class began flaunting their large size, as can be seen in portraits of Henry VIII of England and Alessandro dal Borro.[20] Rubens (1577–1640) regularly depicted heavyset women in his pictures, from which derives the term Rubenesque. These women, however, still maintained the "hourglass" shape with its relationship to fertility.[238] During the 19th century, views on obesity changed in the Western world. After centuries of obesity being synonymous with wealth and social status, slimness began to be seen as the desirable standard.[20] In his 1819 print, The Belle Alliance, or the Female Reformers of Blackburn!!!, artist George Cruikshank criticised the work of female reformers in Blackburn and used fatness as a means to portray them as unfeminine.[239]

Society and culture

Economic impact

In addition to its health impacts, obesity leads to many problems, including disadvantages in employment[240]: 29 [241] and increased business costs.

In 2005, the medical costs attributable to obesity in the US were an estimated $190.2 billion or 20.6% of all medical expenditures,[242][243][244] while the cost of obesity in Canada was estimated at CA$2 billion in 1997 (2.4% of total health costs).[96] The total annual direct cost of overweight and obesity in Australia in 2005 was A$21 billion. Overweight and obese Australians also received A$35.6 billion in government subsidies.[245] The estimated range for annual expenditures on diet products is $40 billion to $100 billion in the US alone.[246]

The Lancet Commission on Obesity in 2019 called for a global treaty—modelled on the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control—committing countries to address obesity and undernutrition, explicitly excluding the food industry from policy development. They estimate the global cost of obesity $2 trillion a year, about or 2.8% of world GDP.[247]

Obesity prevention programs have been found to reduce the cost of treating obesity-related disease. However, the longer people live, the more medical costs they incur. Researchers, therefore, conclude that reducing obesity may improve the public's health, but it is unlikely to reduce overall health spending.[248] Sin taxes such as a sugary drink tax have been implemented in certain countries globally to curb dietary and consumer habits, and as an effort to offset the economic tolls.

Obesity can lead to social stigmatization and disadvantages in employment.[240]: 29 When compared to their normal weight counterparts, obese workers on average have higher rates of absenteeism from work and take more disability leave, thus increasing costs for employers and decreasing productivity.[250] A study examining Duke University employees found that people with a BMI over 40 kg/m2 filed twice as many workers' compensation claims as those whose BMI was 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. They also had more than 12 times as many lost work days. The most common injuries in this group were due to falls and lifting, thus affecting the lower extremities, wrists or hands, and backs.[251] The Alabama State Employees' Insurance Board approved a controversial plan to charge obese workers $25 a month for health insurance that would otherwise be free unless they take steps to lose weight and improve their health. These measures started in January 2010 and apply to those state workers whose BMI exceeds 35 kg/m2 and who fail to make improvements in their health after one year.[252]

Some research shows that obese people are less likely to be hired for a job and are less likely to be promoted.[235] Obese people are also paid less than their non-obese counterparts for an equivalent job; obese women on average make 6% less and obese men make 3% less.[240]: 30

Specific industries, such as the airline, healthcare and food industries, have special concerns. Due to rising rates of obesity, airlines face higher fuel costs and pressures to increase seating width.[253] In 2000, the extra weight of obese passengers cost airlines US$275 million.[254] The healthcare industry has had to invest in special facilities for handling severely obese patients, including special lifting equipment and bariatric ambulances.[255] Costs for restaurants are increased by litigation accusing them of causing obesity.[256] In 2005, the US Congress discussed legislation to prevent civil lawsuits against the food industry in relation to obesity; however, it did not become law.[256]

With the American Medical Association's 2013 classification of obesity as a chronic disease,[23] it is thought that health insurance companies will more likely pay for obesity treatment, counseling and surgery, and the cost of research and development of fat treatment pills or gene therapy treatments should be more affordable if insurers help to subsidize their cost.[257] The AMA classification is not legally binding, however, so health insurers still have the right to reject coverage for a treatment or procedure.[257]

In 2014, The European Court of Justice ruled that morbid obesity is a disability. The Court said that if an employee's obesity prevents them from "full and effective participation of that person in professional life on an equal basis with other workers", then it shall be considered a disability and that firing someone on such grounds is discriminatory.[258]

In low-income countries, obesity can be a signal of wealth. A 2023 experimental study found that obese individuals in Uganda were more likely to access credit.[259]

Size acceptance

The principal goal of the fat acceptance movement is to decrease discrimination against people who are overweight and obese.[261][262] However, some in the movement are also attempting to challenge the established relationship between obesity and negative health outcomes.[263]

A number of organizations exist that promote the acceptance of obesity. They have increased in prominence in the latter half of the 20th century.[264] The US-based National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA) was formed in 1969 and describes itself as a civil rights organization dedicated to ending size discrimination.[265]

The International Size Acceptance Association (ISAA) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) which was founded in 1997. It has more of a global orientation and describes its mission as promoting size acceptance and helping to end weight-based discrimination.[266] These groups often argue for the recognition of obesity as a disability under the US Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA). The American legal system, however, has decided that the potential public health costs exceed the benefits of extending this anti-discrimination law to cover obesity.[263]

Industry influence on research

In 2015, the New York Times published an article on the Global Energy Balance Network, a nonprofit founded in 2014 that advocated for people to focus on increasing exercise rather than reducing calorie intake to avoid obesity and to be healthy. The organization was founded with at least $1.5M in funding from the Coca-Cola Company, and the company has provided $4M in research funding to the two founding scientists Gregory A. Hand and Steven N. Blair since 2008.[267][268]

Reports

Many organizations have published reports pertaining to obesity. In 1998, the first US Federal guidelines were published, titled "Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report".[269] In 2006, the Canadian Obesity Network, now known as Obesity Canada published the "Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) on the Management and Prevention of Obesity in Adults and Children". This is a comprehensive evidence-based guideline to address the management and prevention of overweight and obesity in adults and children.[96]

In 2004, the United Kingdom Royal College of Physicians, the Faculty of Public Health and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health released the report "Storing up Problems", which highlighted the growing problem of obesity in the UK.[270] The same year, the House of Commons Health Select Committee published its "most comprehensive inquiry [...] ever undertaken" into the impact of obesity on health and society in the UK and possible approaches to the problem.[271] In 2006, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued a guideline on the diagnosis and management of obesity, as well as policy implications for non-healthcare organizations such as local councils.[272] A 2007 report produced by Derek Wanless for the King's Fund warned that unless further action was taken, obesity had the capacity to debilitate the National Health Service financially.[273] In 2022 the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) published a comprehensive review of research on what local authorities can do to reduce obesity.[198]

The Obesity Policy Action (OPA) framework divides measure into upstream policies, midstream policies, and downstream policies. Upstream policies have to do with changing society, while midstream policies try to alter behaviors believed to contribute to obesity at the individual level, while downstream policies treat currently obese people.[274]

Childhood obesity

The healthy BMI range varies with the age and sex of the child. Obesity in children and adolescents is defined as a BMI greater than the 95th percentile.[275] The reference data that these percentiles are based on is from 1963 to 1994 and thus has not been affected by the recent increases in rates of obesity.[276] Childhood obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the 21st century, with rising rates in both the developed and the developing world. Rates of obesity in Canadian boys have increased from 11% in the 1980s to over 30% in the 1990s, while during this same time period rates increased from 4 to 14% in Brazilian children.[277] In the UK, there were 60% more obese children in 2005 compared to 1989.[278] In the US, the percentage of overweight and obese children increased to 16% in 2008, a 300% increase over the prior 30 years.[279]

As with obesity in adults, many factors contribute to the rising rates of childhood obesity. Changing diet and decreasing physical activity are believed to be the two most important causes for the recent increase in the incidence of child obesity.[280] Advertising of unhealthy foods to children also contributes, as it increases their consumption of the product.[281] Antibiotics in the first 6 months of life have been associated with excess weight at age seven to twelve years of age.[165] Because childhood obesity often persists into adulthood and is associated with numerous chronic illnesses, children who are obese are often tested for hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and fatty liver disease.[96]

Treatments used in children are primarily lifestyle interventions and behavioral techniques, although efforts to increase activity in children have had little success.[282] In the United States, medications are not FDA approved for use in this age group.[277] Brief weight management interventions in primary care (e.g. delivered by a physician or nurse practitioner) have only a marginal positive effect in reducing childhood overweight or obesity.[283] Multi-component behaviour change interventions that include changes to dietary and physical activity may reduce BMI in the short term in children aged 6 to 11 years, although the benefits are small and quality of evidence is low.[284]

Other animals

Obesity in pets is common in many countries. In the United States, 23–41% of dogs are overweight, and about 5.1% are obese.[285] The rate of obesity in cats was slightly higher at 6.4%.[285] In Australia, the rate of obesity among dogs in a veterinary setting has been found to be 7.6%.[286] The risk of obesity in dogs is related to whether or not their owners are obese; however, there is no similar correlation between cats and their owners.[287]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Obesity and overweight Fact sheet N°311". WHO. January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Haslam DW, James WP (October 2005). "Obesity". Lancet (Review). 366 (9492): 1197–1209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. PMID 16198769. S2CID 208791491.

- ^ a b Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. (March 2010). "Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (3): 220–9. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. PMID 20194822.

- ^ a b Yazdi FT, Clee SM, Meyre D (2015). "Obesity genetics in mouse and human: back and forth, and back again". PeerJ. 3: e856. doi:10.7717/peerj.856. PMC 4375971. PMID 25825681.

- ^ a b c Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA (January 2014). "Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review". JAMA (Review). 311 (1): 74–86. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281361. PMC 3928674. PMID 24231879.

- ^ a b c Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK (August 2014). "Surgery for weight loss in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Meta-analysis, Review). 2014 (8): CD003641. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. PMC 9028049. PMID 25105982.

- ^ a b NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (29 February 2024). "Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults". The Lancet. 403 (10431): 1027–1050. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7615769. PMID 38432237.

- ^ Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. (May 2021). "Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 143 (21): e984–e1010. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973. PMC 8493650. PMID 33882682.

- ^ CDC (21 March 2022). "Causes and Consequences of Childhood Obesity". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Policy Finder". American Medical Association (AMA). Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ a b Kanazawa M, Yoshiike N, Osaka T, Numba Y, Zimmet P, Inoue S (2005). "Criteria and Classification of Obesity in Japan and Asia-Oceania". Nutrition and Fitness: Obesity, the Metabolic Syndrome, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer. World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics. Vol. 94. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1159/000088200. ISBN 978-3-8055-7944-5. PMID 16145245. S2CID 19963495.

- ^ "Obesity - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Chiolero A (October 2018). "Why causality, and not prediction, should guide obesity prevention policy". The Lancet. Public Health. 3 (10): e461–e462. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30158-0. PMID 30177480.

- ^ Kassotis CD, Vandenberg LN, Demeneix BA, Porta M, Slama R, Trasande L (August 2020). "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: economic, regulatory, and policy implications". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 8 (8): 719–730. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30128-5. PMC 7437819. PMID 32707119.

- ^ a b Bleich S, Cutler D, Murray C, Adams A (2008). "Why is the developed world obese?". Annual Review of Public Health (Research Support). 29: 273–295. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090954. PMID 18173389.

- ^ Strohacker K, Carpenter KC, McFarlin BK (15 July 2009). "Consequences of Weight Cycling: An Increase in Disease Risk?". International Journal of Exercise Science. 2 (3): 191–201. doi:10.70252/ASAQ8961. PMC 4241770. PMID 25429313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ignored DOI errors (link) - ^ Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Alvarez EE, Sendra-Gutiérrez JM, González-Enríquez J (July 2008). "Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis". Obesity Surgery. 18 (7): 841–846. doi:10.1007/s11695-007-9331-8. PMID 18459025. S2CID 10220216.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Mental Health (2 ed.). Academic Press. 2015. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-12-397753-3.

- ^ "One in eight people are now living with obesity". World Health Organization. 1 March 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Woodhouse R (2008). "Obesity in Art – A Brief Overview". Obesity in art: a brief overview. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Vol. 36. pp. 271–86. doi:10.1159/000115370. ISBN 978-3-8055-8429-6. PMID 18230908.

- ^ "The implications of defining obesity as a disease: a report from the Association for the Study of Obesity 2021 annual conference - eClinicalMedicine".

- ^ a b c d e f Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. (June 2014). "2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society". Circulation. 129 (25 Suppl 2): S102–S138. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. PMC 5819889. PMID 24222017.

- ^ a b Pollack A (18 June 2013). "A.M.A. Recognizes Obesity as a Disease". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013.

- ^ Weinstock M (21 June 2013). "The Facts About Obesity". H&HN. American Hospital Association. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ The SuRF Report 2 (PDF). The Surveillance of Risk Factors Report Series (SuRF). World Health Organization. 2005. p. 22.

- ^ a b c d "Obesity and overweight". World Health Organization. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "BMI-for-age (5–19 years)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ a b Bei-Fan Z (December 2002). "Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults: study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults". Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 11 (Suppl 8): S685–93. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.s8.9.x.; Originally printed as Zhou BF (March 2002). "Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults--study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults". Biomedical and Environmental Sciences. 15 (1): 83–96. PMID 12046553.

- ^ a b Sturm R (July 2007). "Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000–2005". Public Health. 121 (7): 492–6. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.006. PMC 2864630. PMID 17399752.

- ^ Seidell JC, Flegal KM (1997). "Assessing obesity: classification and epidemiology" (PDF). British Medical Bulletin. 53 (2): 238–252. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011611. PMID 9246834.

- ^ Lin TY, Lim PS, Hung SC (23 December 2017). "Impact of Misclassification of Obesity by Body Mass Index on Mortality in Patients With CKD". Kidney International Reports. 3 (2): 447–455. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2017.12.009. ISSN 2468-0249. PMC 5932305. PMID 29725649.

- ^ "Regular Exercise: How It Can Boost Your Health".

- ^ "NFL Players Not at Increased Heart Risk: Study finds they showed no more signs of cardiovascular trouble than general male population".

- ^ a b Yamauchi T, Abe T, Midorikawa T, Kondo M (2004). "Body composition and resting metabolic rate of Japanese college Sumo wrestlers and non-athlete students: are Sumo wrestlers obese?". Anthropological Science. 112 (2): 179–185. doi:10.1537/ase.040210.

- ^ a b Blüher M (May 2019). "Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 15 (5): 288–298. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8. PMID 30814686. S2CID 71146382.

- ^ a b c d Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. (March 2009). "Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies". Lancet. 373 (9669): 1083–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. PMC 2662372. PMID 19299006.

- ^ Barness LA, Opitz JM, Gilbert-Barness E (December 2007). "Obesity: genetic, molecular, and environmental aspects". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 143A (24): 3016–34. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32035. PMID 18000969. S2CID 7205587.

- ^ Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL (March 2004). "Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000". JAMA. 291 (10): 1238–45. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. PMID 15010446. S2CID 14589790.

- ^ Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, Stevens J, VanItallie TB (October 1999). "Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States". JAMA. 282 (16): 1530–8. doi:10.1001/jama.282.16.1530. PMID 10546692.

- ^ Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, Norat T, Janszky I, Tonstad S, et al. (May 2016). "BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants". BMJ. 353: i2156. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2156. PMC 4856854. PMID 27146380.

- ^ a b Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju S, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. (The Global BMI Mortality Collaboration) (August 2016). "Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents". Lancet. 388 (10046): 776–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1. PMC 4995441. PMID 27423262.

- ^ Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW (October 1999). "Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (15): 1097–105. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910073411501. PMID 10511607.

- ^ Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K, et al. (November 2008). "General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (20): 2105–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. PMID 19005195. S2CID 23967973.

- ^ Carmienke S, Freitag MH, Pischon T, Schlattmann P, Fankhaenel T, Goebel H, et al. (June 2013). "General and abdominal obesity parameters and their combination in relation to mortality: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 67 (6): 573–85. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2013.61. PMID 23511854.

- ^ WHO Expert Consultation (January 2004). "Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies". Lancet. 363 (9403): 157–63. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15268-3. PMID 14726171. S2CID 15637224.

- ^ "Obesity". who.int. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L (January 2003). "Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 138 (1): 24–32. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008. hdl:1765/10043. PMID 12513041. S2CID 8120329.

- ^ Grundy SM (June 2004). "Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (6): 2595–600. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0372. PMID 15181029. S2CID 7453798.

- ^ "Obesity linked to long Covid-19, RAK hospital study finds". Khaleej Times. 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, Rosenblum HG, Belay B, Ko JY, et al. (July 2021). "Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020 – March 2021". Preventing Chronic Disease. 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: E66. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210123. PMC 8269743. PMID 34197283.

- ^ a b c Seidell JC (2005). "Epidemiology – definition and classification of obesity". In Kopelman PG, Caterson ID, Stock MJ, Dietz WH (eds.). Clinical obesity in adults and children: In Adults and Children. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-1-4051-1672-5.

- ^ a b Bray GA (June 2004). "Medical consequences of obesity". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (6): 2583–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0535. PMID 15181027.

- ^ Shoelson SE, Herrero L, Naaz A (May 2007). "Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance". Gastroenterology. 132 (6): 2169–80. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.059. PMID 17498510.

- ^ Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB (July 2006). "Inflammation and insulin resistance". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (7): 1793–801. doi:10.1172/JCI29069. PMC 1483173. PMID 16823477.

- ^ Dentali F, Squizzato A, Ageno W (July 2009). "The metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for venous and arterial thrombosis". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 35 (5): 451–7. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1234140. PMID 19739035. S2CID 260320617.

- ^ Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Ezzati M, Woodward M, Rimm EB, Danaei G (March 2014). "Metabolic mediators of the effects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1·8 million participants". Lancet. 383 (9921): 970–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61836-X. PMC 3959199. PMID 24269108.

- ^ Aune D, Sen A, Norat T, Janszky I, Romundstad P, Tonstad S, et al. (February 2016). "Body Mass Index, Abdominal Fatness, and Heart Failure Incidence and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies". Circulation. 133 (7): 639–49. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016801. PMID 26746176. S2CID 115876581.

- ^ Darvall KA, Sam RC, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW, Adam DJ (February 2007). "Obesity and thrombosis". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 33 (2): 223–33. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.006. PMID 17185009.

- ^ a b c d Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A (June 2007). "Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 56 (6): 901–16, quiz 917–20. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004. PMID 17504714.

- ^ Hahler B (June 2006). "An overview of dermatological conditions commonly associated with the obese patient". Ostomy/Wound Management. 52 (6): 34–6, 38, 40 passim. PMID 16799182.

- ^ a b c Arendas K, Qiu Q, Gruslin A (June 2008). "Obesity in pregnancy: pre-conceptional to postpartum consequences". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 30 (6): 477–488. doi:10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32863-8. PMID 18611299.

- ^ a b c d Dibaise JK, Foxx-Orenstein AE (July 2013). "Role of the gastroenterologist in managing obesity". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 7 (5): 439–51. doi:10.1586/17474124.2013.811061. PMID 23899283. S2CID 26275773.

- ^ Harney D, Patijn J (2007). "Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies". Pain Medicine (Review). 8 (8): 669–77. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00227.x. PMID 18028045.

- ^ Bigal ME, Lipton RB (January 2008). "Obesity and chronic daily headache". Current Pain and Headache Reports (Review). 12 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0011-8. PMID 18417025. S2CID 23729708.

- ^ Sharifi-Mollayousefi A, Yazdchi-Marandi M, Ayramlou H, Heidari P, Salavati A, Zarrintan S, et al. (February 2008). "Assessment of body mass index and hand anthropometric measurements as independent risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome". Folia Morphologica. 67 (1): 36–42. PMID 18335412.

- ^ Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Wang Y (May 2008). "Obesity and central obesity as risk factors for incident dementia and its subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obesity Reviews (Meta-analysis). 9 (3): 204–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00473.x. PMC 4887143. PMID 18331422.

- ^ Wall M (March 2008). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri)". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports (Review). 8 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1007/s11910-008-0015-0. PMID 18460275. S2CID 17285706.

- ^ Munger KL, Chitnis T, Ascherio A (November 2009). "Body size and risk of MS in two cohorts of US women". Neurology (Comparative Study). 73 (19): 1543–50. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c0d6e0. PMC 2777074. PMID 19901245.

- ^ Basen-Engquist K, Chang M (February 2011). "Obesity and cancer risk: recent review and evidence". Current Oncology Reports. 13 (1): 71–6. doi:10.1007/s11912-010-0139-7. PMC 3786180. PMID 21080117.

- ^ a b c Poulain M, Doucet M, Major GC, Drapeau V, Sériès F, Boulet LP, et al. (April 2006). "The effect of obesity on chronic respiratory diseases: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies". CMAJ. 174 (9): 1293–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051299. PMC 1435949. PMID 16636330.

- ^ Poly TN, Islam MM, Yang HC, Lin MC, Jian WS, Hsu MH, et al. (5 February 2021). "Obesity and Mortality Among Patients Diagnosed With COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Medicine. 8: 620044. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.620044. PMC 7901910. PMID 33634150.

- ^ Aune D, Norat T, Vatten LJ (December 2014). "Body mass index and the risk of gout: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies". European Journal of Nutrition. 53 (8): 1591–601. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0766-0. PMID 25209031. S2CID 38095938.

- ^ Tukker A, Visscher TL, Picavet HS (March 2009). "Overweight and health problems of the lower extremities: osteoarthritis, pain and disability". Public Health Nutrition (Research Support). 12 (3): 359–68. doi:10.1017/S1368980008002103 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 18426630.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Molenaar EA, Numans ME, van Ameijden EJ, Grobbee DE (November 2008). "[Considerable comorbidity in overweight adults: results from the Utrecht Health Project]". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (English abstract) (in Dutch). 152 (45): 2457–63. PMID 19051798.

- ^ Corona G, Rastrelli G, Filippi S, Vignozzi L, Mannucci E, Maggi M (2014). "Erectile dysfunction and central obesity: an Italian perspective". Asian Journal of Andrology. 16 (4): 581–91. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.126386. PMC 4104087. PMID 24713832.

- ^ Hunskaar S (2008). "A systematic review of overweight and obesity as risk factors and targets for clinical intervention for urinary incontinence in women". Neurourology and Urodynamics (Review). 27 (8): 749–57. doi:10.1002/nau.20635. PMID 18951445. S2CID 20378183.

- ^ Ejerblad E, Fored CM, Lindblad P, Fryzek J, McLaughlin JK, Nyrén O (June 2006). "Obesity and risk for chronic renal failure". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (Research Support). 17 (6): 1695–702. doi:10.1681/ASN.2005060638. PMID 16641153.

- ^ Makhsida N, Shah J, Yan G, Fisch H, Shabsigh R (September 2005). "Hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome: implications for testosterone therapy". The Journal of Urology (Review). 174 (3): 827–34. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.612.1060. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000169490.78443.59. PMID 16093964.

- ^ Pestana IA, Greenfield JM, Walsh M, Donatucci CF, Erdmann D (October 2009). "Management of "buried" penis in adulthood: an overview". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (Review). 124 (4): 1186–95. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b5a37f. PMID 19935302. S2CID 36775257.

- ^ Denis GV, Hamilton JA (October 2013). "Healthy obese persons: how can they be identified and do metabolic profiles stratify risk?". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 20 (5): 369–376. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000433058.78485.b3. PMC 3934493. PMID 23974763.

- ^ a b Blüher M (May 2020). "Metabolically Healthy Obesity". Endocrine Reviews. 41 (3): bnaa004. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnaa004. PMC 7098708. PMID 32128581.

- ^ a b c Smith GI, Mittendorfer B, Klein S (October 2019). "Metabolically healthy obesity: facts and fantasies". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 129 (10): 3978–3989. doi:10.1172/JCI129186. PMC 6763224. PMID 31524630.

- ^ Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, et al. (July 2016). "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for Medical Care of Patients with Obesity". Endocrine Practice. 22 (Suppl 3): 1–203. doi:10.4158/EP161365.GL. PMID 27219496. S2CID 3996442.