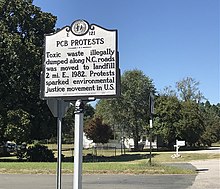

Warren County PCB Landfill

Warren County PCB Landfill was a PCB landfill located in Warren County, North Carolina, near the community of Afton south of Warrenton. The landfill was created in 1982 by the State of North Carolina as a place to dump contaminated soil as result of an illegal PCB dumping incident. The site, which is about 150 acres (0.61 km2), was extremely controversial and led to years of lawsuits. Warren County was one of the first cases of environmental justice in the United States and set a legal precedent for other environmental justice cases. The site was approximately three miles south of Warrenton. The State of North Carolina owned about 19 acres (77,000 m2) of the tract where the landfill was located, and Warren County owned the surrounding acreage around the borders.[1]

Purpose

[edit]The purpose of the Warren County PCB landfill, as the public knew it, was to bury 60,000 tons of PCB-contaminated soil that had been contaminated with toxic PCBs between June and August, 1978, by Robert J. Burns, a business associate with Robert "Buck" Ward of the Ward PCB Transformer Company of Raleigh, North Carolina. Burns and his sons deliberately dripped 31,000 gallons of PCB-contaminated oil along some 240 miles of highway shoulders in 14 counties.[2][3] Burns of Jamestown, New York, was supposed to take the oil to a facility to be recycled. Allegedly, the rationale for Burns' crime was that he wanted to save money by circumventing new Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations that would make waste disposal more transparent and costly. But he could have easily, discreetly, and illegally disposed of the PCB-contaminated oil in a matter of hours. Burns and Ward were sent to prison for a short time for their involvement in the crime. The Ward Transformer site would later go onto the EPA Superfund cleanup list and be the primary polluter of Lake Crabtree and the Neuse River basin in the vicinity of Raleigh, North Carolina. Contaminants from the Ward site have been detoxified, but the area around the site and surrounding creeks, lakes, and rivers have been permanently polluted.

Soon after the "midnight PCB dumpings," the state erected large warning signs along the roadsides, making the public feel as if the roadside PCBs posed an imminent public health threat. However, the Hunt administration let the PCBs remain for four years as they spread into the environment, while Warren County citizens opposed the PCB landfill. The Governor, the North Carolina General Assembly, and the EPA found they would have to make the political, legal, and regulatory preparations to forcibly bury the PCBs in Warren County.

The Warren County PCB landfill was permitted as a "dry-tomb" toxic waste landfill by the EPA under the Toxic Substances Control Act. The EPA approved the "dry-tomb" PCB landfill which failed from the beginning because it was capped with nearly a million gallons of water in it. After that, the site never operated as a commercial facility because residents forced the Governor to include in the deed that it was a one-time only toxic waste facility. The landfill was built with plastic liners, a clay cap, and PVC pipes which allowed for methane and toxic gas to be released from the landfill. Although state officials told citizens they planned to build the landfill with a perforated pipe leachate collection system under the landfill, a system critical to a functioning "dry-tomb" landfill, no such leachate collection system was ever installed. The nearly 1 million gallons of water that was capped in the "dry-tomb" landfill could not be pumped out, and citizens later learned from state rainfall and landfill monitoring data that tens of thousands of gallons of water had been entering and exiting the landfill for years. Within a few months of burying the PCBs, EPA found significant PCB air emissions at the landfill and 1/2 mile away, but citizens did not learn about this report for another 15 years. The 60,000 tons of PCB-contaminated soil were buried within about 7 feet of groundwater. Warren County's first independent scientist, Dr. Charles Mulchi, had predicted that the landfill would inevitably fail because of unsuitable soils and close proximity to groundwater. He had pointed out at a January 4, 1979, EPA public hearing that state scientists had misrepresented the depths of soil sample testing they had conducted at the site. At Mulchi's insistence, the state added a plastic top liner to the landfill.

According to detoxification expert Dr. Joel Hirshhorn, who represented Warren County citizens as they pressed Governor Hunt and the North Carolina General Assembly for funding for a cleanup, the Warren county PCB landfill was an utter failure that should never have been approved by the EPA.[4]

Controversy

[edit]

Beginning with Governor Hunt's administration's December 20, 1978, announcement that "public sentiment would not deter the state from burying the PCBs in Warren County," the PCB landfill was surrounded by controversy. The landfill was located in rural Warren County, which was primarily African American. Warren County has about 18,000 people living in the county. Sixty-nine percent of the residents are non-white, and twenty percent of the residents live below the federal poverty level. The county has been determined as a Tier I county for economic development. The residence of the poor and predominantly African-American Warren County, North Carolina opposed the development there of a landfill designed to contain large quantities of soil contaminated with PCBs. Although the coalition lost the battle to stop the landfill, the protesters obtained numerous concessions from the state over the years.[5] The state claimed that the Warren County site was the best available site; however, the site selection process was not based on scientific criteria — soil permeability properties or the distance to groundwater — but on other, less tangible criteria, including the demographics of the county. EPA and state officials claimed they could compensate for improper soil qualities and the close proximity to groundwater with the engineering design of their "state-of-the-art", "dry-tomb", zero-percent discharge landfill.

An article from 1996 said, “North Carolina’s PCB landfill in Warren County leaks about a half an inch of water a year”. State data on rainfall during 1996 and water levels inside the dump indicate 30,000 gallons of water flow into the site each year and 26,000 gallons flow out. During this time it is said that citizens and some members of the working group urge Governor Hunt to clean up the dump and detoxify the PCB contaminated soil. The PCBs came from dirt roads in the state where the chemical was dumped illegally in the 70s.[6]

After four years, Warren County citizens officially launched the environmental justice movement as they lay in front of 10,000 truckloads of contaminated PCB soil. During the six-week trucking opposition, with collective nonviolent direct action, which included over 550 arrests, Warren County citizens mounted what the Duke Chronicle described as "the largest civil disobedience in the South since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., marched through Alabama."[7] It was the first time in American history that citizens were jailed for trying to stop a landfill, from attempting to prevent pollution. In an editorial titled "Dumping on the Poor," The Washington Post described Warren County's PCB protest movement as "the marriage of environmentalism with civil rights," and in its 1994 Environmental Equity Draft, the EPA described the PCB protest movement as "the watershed event that led to the environmental equity movement of the 1980's." With public pressure mounting, Governor Hunt then pledged to Warren citizens that when technology became available, the state would detoxify the PCB landfill.[4][8] The resulting controversy led to the coining of the phrase "environmental racism" and galvanized the environmental justice movement.[9]

Soon after, academics and scholars began research and case studies to provide further evidence linking poor in minority neighborhoods across the country with a higher level of environmental hazards.[10] The Warren County protest led the commission of racial justice to produce "Toxic Waste and Race", the first national study to correlate waste facilities sites and demographic characteristics. Race was found to be the most potent variable in predicting where these facilities were located; more powerful than poverty, land values, and home ownership.[11]

Decontamination

[edit]In May, 1993, more than 10 years after the Governor promised to detoxify the PCB landfill when it became feasible, and soon after stopping a huge trash landfill to be located near the PCB landfill, citizens learned that there was "an emergency" at the PCB landfill because of nearly a million gallons of water in that landfill that threatened to breach the liner. Speaking and negotiating for Warren County citizens as he had done a decade before, Ken Ferruccio laid out a 5-Point Framework for resolving the PCB landfill crisis and demanded from the Hunt administration (Governor Jim Hunt's 3rd of 4 terms in office):

- The state continue to monitor and maintain the PCB landfill

- A joint citizen/state committee be formed to mutually address the failures of the PCB landfill

- The solution to the failed PCB landfill remain on site

- Citizens be given independent scientific representation

- Permanent detoxification of the PCB landfill be the ultimate goal

Governor Hunt agreed to the Framework and the Joint Warren County/State PCB Landfill Working Group was formed.

In 1999, the North Carolina General Assembly promised about eight million dollars to go towards cleanup with another group would be willing to match it. The EPA was deemed a "match" and the cleanup project was able to move forward. In November 2000 an environmental engineering firm, Earth Tech, was hired to serve as the oversight contractor.

In December 2000, public bids were taken for the site-detoxifying contract. The IT Corporation was awarded the contract, with their bid of 13.5 million dollars. Phase I of the cleanup process began, and the contract was signed in March 2001. The IT Corporation was bought by the Shaw Group in May 2002 and changed their name to Shaw Environmental and Infrastructure. The equipment was sent to the landfill in May 2002, and an open house was held so community members could view the site before the start-up.

The follow-up tests on the site were performed in 2002. The EPA demonstrated test onto the PCB Landfill in January 2003. Based on the test results, an interim operations permit was granted in March. The soil treatment was then completed in October 2003, and in total 81,600 tons of soil was treated for the landfill site. The soil which was treated was the soil that was on the roadside and the soil adjacent to it that had been in the landfill and had been cross-contaminated. The equipment at the site was decontaminated and removed from the site at the end of 2003. The final cost of the cleanup project of the landfill was 17.1 million dollars. (Much of this money paid for various costly studies and administrative costs. It was not the price of the actual detoxification.) The Based Catalyzed Decomposition detoxification was completed in 2004. Decades after the initial incident the state of North Carolina was required to spend over $25 million to clean up and detoxify the Warren County PCBs landfill.[4][11][12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bullard, Robert. "Environmental Racism PCB Landfill Finally Remedied But No Reparations for Residents". Environmental Justice Resource Center. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "UNITED STATES v. WARD | 676 F.2d 94 (1982) | 76f2d941753 | Leagle.com". Leagle. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ "History". 26 January 2012.

- ^ a b c "NC PCB Archives | Birth of a Movement – Environmental Justice & Pollution Prevention". 2022-01-30. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ O'Connor, R.E. (July 2007). "Transforming environmentalism: Warren County, PCBs, and the origins of environmental justice". Choice. 44 (11). Middletown: 1978. ProQuest 225729031.

- ^ "THE STATE; WARREN COUNTY; Scientists report PCB landfill appears to leak". Morning Star. Wilmington, N.C. 13 November 1996. p. 5B. ProQuest 285416876.

- ^ "FY2022 US EPA Brownfields Assessment Grant" (PDF). www.epa.gov. 2022. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-10-03.

- ^ Labalme, Jenny (1987). A road to walk: A struggle for environmental justice. Durham, NC: The Regulator Press.

- ^ Pezzullo, Phaedra C. (March 2001). "Performing critical interruptions: Stories, rhetorical invention, and the environmental justice movement". Western Journal of Communication. 65 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/10570310109374689. S2CID 143945039.

- ^ Blum, Elizabeth (2007). "Warren County, N.C.". In Melosi, Martin; Wilson, Charles Reagan (eds.). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 8: Environment. North Carolina Press. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-1-4696-1660-5. JSTOR 10.5149/9781469616605_melosi.102.

- ^ a b Bullard, Robert D. (2001). "Environmental Justice in the 21st Century: Race Still Matters". Phylon. 49 (3/4): 151–171. doi:10.2307/3132626. JSTOR 3132626.

- ^ "Warren County PCB Landfill Fact Sheet". North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

External links

[edit]- Real People — Real Stories: Seeking Environmental Justice | Afton, NC (Warren County) Summary

- University of North Carolina Exchange Project full case study

- NC PCB Archives

- Environmental Justice Resource Center | Environmental Racism PCB Landfill Finally Remedied But No Reparations for Residents

- Solid Waste Digest: Fights Result In Toxic Waste Removal From Warren County

- Earth Keeping: Environmental Racism | WGBH Documentary