NSA warrantless surveillance (2001–2007)

National Security Agency surveillance |

|---|

|

NSA warrantless surveillance — also commonly referred to as "warrantless-wiretapping" or "-wiretaps" — was the surveillance of persons within the United States, including U.S. citizens, during the collection of notionally foreign intelligence by the National Security Agency (NSA) as part of the Terrorist Surveillance Program.[1] In late 2001, the NSA was authorized to monitor, without obtaining a FISA warrant, phone calls, Internet activities, text messages and other forms of communication involving any party believed by the NSA to be outside the U.S., even if the other end of the communication lies within the U.S.

Critics claimed that the program was an effort to silence critics of the Bush administration and its handling of several controversial issues. Under public pressure, the Administration allegedly ended the program in January 2007 and resumed seeking warrants from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC).[2] In 2008, Congress passed the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which relaxed some of the original FISC requirements.

During the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) continued to defend the warrantless surveillance program in court, arguing that a ruling on the merits would reveal state secrets.[3] In April 2009, officials at the DOJ acknowledged that the NSA had engaged in "overcollection" of domestic communications in excess of the FISC's authority, but claimed that the acts were unintentional and had since been rectified.[4]

History

[edit]A week after the 9/11 attacks, Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists (AUMF), which inaugurated the "War on Terror". It later featured heavily in arguments over the NSA program.

Soon after the 9/11 attacks, President Bush established the President's Surveillance Program. As part of the program, the Terrorist Surveillance Program was established pursuant to an executive order that authorized the NSA to surveil certain telephone calls without obtaining a warrant (see 50 U.S.C. § 1802 50 U.S.C. § 1809). The complete details of the executive order are not public, but according to administration statements,[5] the authorization covers communication originating overseas from or to a person suspected of having links to terrorist organizations or their affiliates even when the other party to the call is within the US.

In October 2001, Congress passed the Patriot Act, which granted the administration broad powers to fight terrorism.[6] The Bush administration used these powers to bypass the FISC and directed the NSA to spy directly on al-Qaeda via a new NSA electronic surveillance program. Reports at the time indicate that "apparently accidental ... technical glitches at the National Security Agency" resulted in the interception of communications that were between two U.S. parties.[7] This act was challenged by multiple groups, including Congress, as unconstitutional.

The precise scope of the program remains secret, but the NSA was provided total, unsupervised access to all fiber-optic communications between the nation's largest telecommunication companies' major interconnected locations, encompassing phone conversations, email, Internet activity, text messages and corporate private network traffic.[8]

FISA makes it illegal to intentionally engage in electronic surveillance as an official act or to disclose or use information obtained by such surveillance under as an official act, knowing that it was not authorized by statute; this is punishable with a fine of up to $10,000, up to five years in prison or both.[9] The Wiretap Act prohibits any person from illegally intercepting, disclosing, using or divulging phone calls or electronic communications; this is punishable with a fine, up to five years in prison, or both.[10]

After an article about the program, (which had been code-named Stellar Wind), was published in The New York Times on December 16, 2005, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales confirmed its existence.[11][12][13] The Times had published the story after learning that the Bush administration was considering seeking a court injunction to block publication.[14] Bill Keller, the newspaper's executive editor, had withheld the story from publication since before the 2004 Presidential Election. The published story was essentially the same that reporters James Risen and Eric Lichtblau had submitted in 2004. The delay drew criticism, claiming that an earlier publication could have changed the election's outcome.[15] In a December 2008 interview, former Justice Department employee Thomas Tamm claimed to be the initial whistle-blower.[16] The FBI began investigating leaks about the program in 2005, assigning 25 agents and five prosecutors.[17]

Attorney and author Glenn Greenwald argued:[18]

Congress passed a law in 1978 making it a criminal offense to eavesdrop on Americans without judicial oversight. Nobody of any significance ever claimed that that law was unconstitutional. The Administration not only never claimed it was unconstitutional, but Bush expressly asked for changes to the law in the aftermath of 9/11, thereafter praised the law, and misled Congress and the American people into believing that they were complying with the law. In reality, the Administration was secretly breaking the law, and then pleaded with The New York Times not to reveal this. Once caught, the Administration claimed it has the right to break the law and will continue to do so.

Gonzales said the program authorized warrantless intercepts where the government had "a reasonable basis to conclude that one party to the communication is a member of al Qaeda, affiliated with al Qaeda, or a member of an organization affiliated with al Qaeda, or working in support of al Qaeda" and that one party to the conversation was "outside of the United States".[19] The revelation raised immediate concern among elected officials, civil rights activists, legal scholars and the public at large about the legality and constitutionality of the program and its potential for abuse. The controversy expanded to include the press's role in exposing a classified program, Congress's role and responsibility of executive oversight and the scope and extent of presidential powers.[20]

CRS released a report on the NSA program, "Presidential Authority to Conduct Warrantless Electronic Surveillance to Gather Foreign Intelligence Information", on January 5, 2006 that concluded:

While courts have generally accepted that the President has the power to conduct domestic electronic surveillance within the United States inside the constraints of the Fourth Amendment, no court has held squarely that the Constitution disables the Congress from endeavoring to set limits on that power. To the contrary, the Supreme Court has stated that Congress does indeed have power to regulate domestic surveillance, and has not ruled on the extent to which Congress can act with respect to electronic surveillance to collect foreign intelligence information.[21][22][23]

On January 18, 2006 the Congressional Research Service released another report, "Statutory Procedures Under Which Congress Is To Be Informed of U.S. Intelligence Activities, Including Covert Actions".[24][25] That report found that "[b]ased upon publicly reported descriptions of the program, the NSA surveillance program would appear to fall more closely under the definition of an intelligence collection program, rather than qualify as a covert action program as defined by statute", and, therefore, found no specific statutory basis for limiting briefings on the terrorist surveillance program.[26] However, the report goes on to note in its concluding paragraph that limited disclosure is also permitted under the statute "in order to protect intelligence sources and methods".[27]

Legal action

[edit]While not directly ruling on the legality of domestic surveillance, the Supreme Court can be seen as having come down on both sides of the Constitution/statute question, in somewhat analogous circumstances.

In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2004) the government claimed that AUMF authorized the detention of U.S. citizens designated as an enemy combatant despite its lack of specific language to that effect and notwithstanding the provisions of 18 U.S.C. § 4001(a) that forbids the government to detain an American citizen except by act of Congress. In that case, the Court ruled:

[B]ecause we conclude that the Government's second assertion ["that § 4001(a) is satisfied, because Hamdi is being detained "pursuant to an Act of Congress" [the AUMF]"] is correct, we do not address the first. In other words, for the reasons that follow, we conclude that the AUMF is explicit congressional authorization for the detention of individuals ... and that the AUMF satisfied § 4001(a)'s requirement that a detention be "pursuant to an Act of Congress".

However, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld the Court rejected the government's argument that AUMF implicitly authorized the President to establish military commissions in violation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. The Court held:

Neither of these congressional Acts, [AUMF or ATC] however, expands the President's authority to convene military commissions. First, while we assume that the AUMF activated the President's war powers, see Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004)) (plurality opinion), and that those powers include the authority to convene military commissions in appropriate circumstances, see id., at 518; Quirin, 317 U. S., at 28–29; see also Yamashita, 327 U. S., at 11, there is nothing in the text or legislative history of the AUMF even hinting that Congress intended to expand or alter the authorization set forth in Article 21 of the UCMJ. Cf. Yerger, 8 Wall., at 105 ("Repeals by implication are not favored")

In footnote 23, the Court rejected the notion that Congress is impotent to regulate the exercise of executive war powers:

Whether or not the President has independent power, absent congressional authorization, to convene military commissions, he may not disregard limitations that Congress has, in proper exercise of its own war powers, placed on his powers. See Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S. 579, 637 (1952) (Jackson, J., concurring). The Government does not argue otherwise.

Dozens of civil suits against the government and telecommunications companies over the program were consolidated before the chief judge of the Northern District of California, Vaughn R. Walker. One of the cases was a class-action lawsuit against AT&T, focusing on allegations that the company had provided the NSA with its customers' phone and Internet communications for a data-mining operation. Plaintiffs in a second case were the al-Haramain Foundation and two of its lawyers.[28][29]

On August 17, 2006, Judge Anna Diggs Taylor of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan ruled in ACLU v. NSA that the Terrorist Surveillance Program was unconstitutional under the Fourth and First Amendments and enjoined the NSA from using the program to conduct electronic surveillance "in contravention of [FISA or Title III]".[30] She wrote:[31]

The President of the United States, a creature of the same Constitution which gave us these Amendments, has indisputably violated the Fourth in failing to procure judicial orders as required by FISA, and accordingly has violated the First Amendment Rights of these Plaintiffs as well.

In August 2007, a three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit heard arguments in two lawsuits challenging the program. On November 16, 2007, the three judges—M. Margaret McKeown, Michael Daly Hawkins and Harry Pregerson—issued a 27-page ruling that the al-Haramain Foundation could not introduce a key piece of evidence because it fell under the government's claim of state secrets, although the judges said that "In light of extensive government disclosures, the government is hard-pressed to sustain its claim that the very subject matter of the litigation is a state secret."[32][33]

In a question-and-answer session published on August 22, Director of National Intelligence Mike McConnell first confirmed that the private sector had helped the program. McConnell argued that the companies deserved immunity for their help: "Now if you play out the suits at the value they're claimed, it would bankrupt these companies."[34] Plaintiffs in the AT&T suit subsequently moved to have McConnell's acknowledgement admitted as evidence.[35]

This section needs to be updated. (March 2018) |

In a related legal development, on October 13, 2007, Joseph Nacchio, the former CEO of Qwest Communications, appealed an April 2007 insider trading conviction by alleging that the government withdrew opportunities for contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars after Qwest refused to participate in an unidentified NSA program that the company thought might be illegal. He claimed that the NSA approached Qwest about participating in a warrantless surveillance program more than six months before 9/11. Nacchio used the allegation to show why his stock sale was not improper.[36] According to a lawsuit filed against other telecommunications companies for violating customer privacy, AT&T began preparing facilities for the NSA to monitor "phone call information and Internet traffic" seven months before 9/11.[37]

On January 20, 2006, cosponsors Senator Patrick Leahy and Ted Kennedy introduced Senate Resolution 350, a resolution "expressing the sense of the Senate that Senate Joint Resolution 23 (107th Congress), as adopted by the Senate on September 14, 2001, and subsequently enacted as the Authorization for Use of Military Force does not authorize warrantless domestic surveillance of United States citizens".[38][39] This non-binding resolution died without debate.[40]

On September 28, 2006, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Electronic Surveillance Modernization Act (H.R. 5825).[41] It died in the Senate. Three competing, mutually exclusive, bills—the Terrorist Surveillance Act of 2006 (S.2455), the National Security Surveillance Act of 2006 (S.2455) and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Improvement and Enhancement Act of 2006 (S.3001) – were referred for debate to the full Senate,[42] but did not pass. Each of these bills would have broadened the statutory authorization for electronic surveillance, while subjecting it to some restrictions.

Termination

[edit]On January 17, 2007, Gonzales informed Senate leaders that the program would not be reauthorized.[2] "Any electronic surveillance that was occurring as part of the Terrorist Surveillance Program will now be conducted subject to the approval of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court," according to his letter.[43]

Further legal action

[edit]The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued NSA over the program. Detroit District Court judge Anna Diggs Taylor ruled on August 17, 2006 that the program was illegal under FISA as well as unconstitutional under the First and Fourth amendments of the Constitution.[44][30][45] Judicial Watch, a watchdog group, discovered that at the time of the ruling Taylor "serves as a secretary and trustee for a foundation that donated funds to the ACLU of Michigan, a plaintiff in the case".[46]

ACLU v. NSA was dismissed on January 31, 2007 by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.[47] The court did not rule on the spying program's legality. Instead, it declared that the plaintiffs did not have standing to sue because they could not demonstrate that they had been direct targets of the program.[48] The Supreme Court let the ruling stand.

On August 17, 2007, FISC said it would consider a request by the ACLU that asked the court to make public its recent, classified rulings on the scope of the government's wiretapping powers. FISC presiding judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly signed an order calling the ACLU's motion "an unprecedented request that warrants further briefing".[49] The FISC ordered the government to respond on the issue by August 31.[50][51] On the August 31 deadline, the National Security Division of the Justice Department filed a response in opposition to the ACLU's motion.[52] On February 19, 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court, without comment, turned down an ACLU appeal, letting stand the earlier decision dismissing the case.[53]

On September 18, 2008, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) sued the NSA, President Bush, Vice President Cheney, Cheney's chief of staff David Addington, Gonzales and other government agencies and individuals who ordered or participated in the program. They sued on behalf of AT&T customers. An earlier, ongoing suit (Hepting v. AT&T) by the EFF bogged down over the recent FISA changes.[54][55]

On January 23, 2009, the Obama administration adopted the same position as its predecessor when it urged Judge Walker to set aside a ruling in Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation et al. v. Obama, et al.[56] The Obama administration sided with the Bush administration in its legal defense of July 2008 legislation that immunized the nation's telecommunications companies from lawsuits accusing them of complicity in the program, according to Attorney General Eric Holder.[57]

On March 31, 2010, Judge Walker ruled that the program was illegal when it intercepted phone calls of Al Haramain. Declaring that the plaintiffs had been "subjected to unlawful surveillance", the judge said the government was liable for damages.[58] In 2012, the Ninth Circuit vacated the judgment against the United States and affirmed the district court's dismissal of the claim.[59]

Proposed FISA amendments

[edit]Several commentators raised the issue of whether FISA needed to be amended to address foreign intelligence needs, technology developments and advanced technical intelligence gathering. The intent was to provide programmatic approvals of surveillance of foreign terrorist communications, so that they could then legally be used as evidence for FISA warrants. Fixing Surveillance;[60] Why We Listen,[61] The Eavesdropping Debate We Should be Having;[62] A New Surveillance Act;[63] A historical solution to the Bush spying issue,[64] Whispering Wires and Warrantless Wiretaps[65] address FISA's inadequacies in the post-9/11 context.

The Bush administration contended that amendment was unnecessary because they claimed that the President had inherent authority to approve the NSA program, and that the process of amending FISA might require disclosure of classified information that could harm national security.[19] In response, Senator Leahy said, "If you do not even attempt to persuade Congress to amend the law, you must abide by the law as written."[66] President Bush claimed that the law did not apply because the Constitution gave him "inherent authority" to act.[67][68]

Some politicians and commentators used "difficult, if not impossible" to argue that the administration believed Congress would have rejected an amendment. In his written "Responses to Questions from Senator Specter" in which Specter specifically asked why the administration had not sought to amend FISA,[69] Gonzales wrote:

[W]e were advised by members of Congress that it would be difficult, if not impossible to pass such legislation without revealing the nature of the program and the nature of certain intelligence capabilities. That disclosure would likely have harmed our national security, and that was an unacceptable risk we were not prepared to take.

Competing legislative proposals to authorize the NSA program subject to Congressional or FISC oversight were the subject of Congressional hearings.[70] On March 16, 2006, Senators Mike DeWine, Lindsey Graham, Chuck Hagel and Olympia Snowe introduced the Terrorist Surveillance Act of 2006 (S.2455),[71][72] that gave the President limited statutory authority to conduct electronic surveillance of suspected terrorists in the US, subject to enhanced Congressional oversight. That day Specter introduced the National Security Surveillance Act of 2006 (S.2453),[73][74] which would amend FISA to grant retroactive amnesty[75] for warrantless surveillance conducted under presidential authority and provide FISC jurisdiction to review, authorize and oversee "electronic surveillance programs". On May 24, 2006, Specter and Feinstein introduced the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Improvement and Enhancement Act of 2006 (S.3001) denoting FISA as the exclusive means to conduct foreign intelligence surveillance.

On September 13, 2006, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted to approve all three, mutually exclusive bills, thus, leaving it to the full Senate to resolve.[42]

On July 18, 2006, U.S. Representative Heather Wilson introduced the Electronic Surveillance Modernization Act (H.R. 5825). Wilson's bill would give the President the authority to authorize electronic surveillance of international phone calls and e-mail linked specifically to identified terrorist groups immediately following or in anticipation of an armed or terrorist attack. Surveillance beyond the initially authorized period would require a FISA warrant or a presidential certification to Congress. On September 28, 2006 the House of Representatives passed Wilson's bill and it was referred to the Senate.[41]

Each of these bills would in some form broaden the statutory authorization for electronic surveillance, while still subjecting it to some restrictions. The Specter-Feinstein bill would extend the peacetime period for obtaining retroactive warrants to seven days and implement other changes to facilitate eavesdropping while maintaining FISC oversight. The DeWine bill, the Specter bill, and the Electronic Surveillance Modernization Act (already passed by the House) would all authorize some limited forms or periods of warrantless electronic surveillance subject to additional programmatic oversight by either the FISC (Specter bill) or Congress (DeWine and Wilson bills).

FISC order

[edit]On January 18, 2007, Gonzales told the Senate Judiciary Committee,

Court orders issued last week by a Judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court will enable the government to conduct electronic surveillance – very specifically, surveillance into or out of the United States where there is probable cause to believe that one of the communicants is a member or agent of al Qaeda or an associated terrorist organization – subject to the approval of the FISC. We believe that the court's orders will allow the necessary speed and agility the government needs to protect our Nation from the terrorist threat.[76]

The ruling by the FISC was the result of a two-year effort between the White House and the court to find a way to obtain court approval that also would "allow the necessary speed and agility" to find terrorists, Gonzales said in a letter to the top committee members. The court order on January 10 will do that, Gonzales wrote. Senior Justice department officials would not say whether the orders provided individual warrants for each wiretap or whether the court had given blanket legal approval for the entire NSA program. The ACLU said in a statement that "without more information about what the secret FISC has authorized, there is no way to determine whether the NSA's current activities are lawful".[77] Law professor Chip Pitts argued that substantial legal questions remain regarding the core NSA program as well as the related data mining program (and the use of National Security Letters), despite the government's apparently bringing the NSA program within the purview of FISA.[78]

FISCR ruling

[edit]In August 2008, the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review (FISCR) affirmed the constitutionality of the Protect America Act of 2007 in a heavily redacted opinion released on January 15, 2009, only the second such public ruling since the enactment of the FISA Act.[79][80][81][82][83]

Relevant constitutional, statutory and administrative provisions

[edit]U.S. Constitution

[edit]Article I and II

[edit]Article I vests Congress with the sole authority "To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces" and "To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof." The Supreme Court has used the "necessary and proper" clause to affirm broad Congressional authority to legislate as it sees fit in the domestic arena,[84] but has limited its application in foreign affairs. In the landmark US v. Curtiss-Wright (1936) decision, Justice George Sutherland for the Court:

The ["powers of the federal government in respect of foreign or external affairs and those in respect of domestic or internal affairs"] are different, both in respect of their origin and their nature. The broad statement that the federal government can exercise no powers except those specifically enumerated in the Constitution, and such implied powers as are necessary and proper to carry into effect the enumerated powers, is categorically true only in respect of our internal affairs.

Article II vests the President with power as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States," and requires that the President "shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed".

Fourth Amendment

[edit]The Fourth Amendment is part of the Bill of Rights and prohibits "unreasonable" searches and seizures by the government. A search warrant must be judicially sanctioned, based on probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation (usually by a law enforcement officer), particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized, limited in scope (according to specific information supplied to the issuing court). It is solely a right of the people that neither the Executive nor Legislative branch can lawfully abrogate, even if acting in concert: no statute can make an unreasonable search reasonable.

The term "unreasonable" connotes the sense that a constitutional search has a rational basis, that it is not an excessive imposition upon the individual given the circumstances and is in accordance with societal norms. It relies on judges to be sufficiently independent of the authorities seeking warrants that they can render an impartial decision. Evidence obtained in an unconstitutional search is inadmissible in a criminal trial (with certain exceptions).

The Fourth Amendment explicitly allows reasonable searches, including searches without warrant in specific circumstances. Such circumstances include the persons, property and papers of individuals crossing the border of the United States and those of paroled felons; prison inmates, public schools and government offices; and of international mail. Although these are undertaken pursuant to a statute or an executive order, they derive their legitimacy from the Amendment, rather than these.

Ninth and Tenth Amendments

[edit]The Tenth Amendment explicitly states that powers neither granted to the federal government nor prohibited to the states are reserved to the states or the people. The Ninth Amendment states, "The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people."

The Ninth Amendment bars denial of unenumerated rights if the denial is based on the "enumeration of certain rights" in the Constitution, but does not bar denial of unenumerated rights if the denial is based on the "enumeration of certain powers" in the Constitution.[85]

Related Court opinions

[edit]The Supreme Court has historically used Article II to justify wide deference to the President in foreign affairs.[86] Two historical and recent cases define the secret wiretapping by the NSA. Curtiss-Wright:

It is important to bear in mind that we are here dealing not alone with an authority vested in the President by an exertion of legislative power, but with such an authority plus the very delicate, plenary and exclusive power of the President as the sole organ of the federal government in the field of international relations–a power which does not require as a basis for its exercise an act of Congress, but which, of course, like every other governmental power, must be exercised in subordination to the applicable provisions of the Constitution.

The extent of the President's power as Commander-in-Chief has never been fully defined, but two Supreme Court cases are considered seminal in this area:[87][88] Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952) and Curtiss-Wright.

The Supreme Court held in Katz v. United States (1967), that the monitoring and recording of private conversations within the United States constitutes a "search" for Fourth Amendment purposes, and therefore require a warrant.

The Supreme Court held in Smith v Maryland (1979) that a judicial warrant is required for the government to acquire the content of electronic communications. However, subpoenas but not warrants are required for the business records ( metadata) of their communications, data such as the numbers that an individual has phoned, when and, to a limited degree, where the phone conversation occurred.

The protection of "private conversations" has been held to apply only to conversations where the participants have manifested both a desire and a reasonable expectation that their conversation is indeed private and that no other party is privy to it. In the absence of such a reasonable expectation, the Fourth Amendment does not apply, and surveillance without warrant does not violate it. Privacy is clearly not a reasonable expectation in communications to persons in the many countries whose governments openly intercept electronic communications, and is of dubious reasonability in countries against which the United States is waging war.

Various Circuit Courts upheld warrantless surveillance when the target was a foreign agent residing abroad,[89][90] a foreign agent residing in the US[91][92][93][94] and a US citizen abroad.[95] The exception does not apply when both the target and the threat were deemed domestic.[96] The legality of targeting US persons acting as agents of a foreign power and residing in this country has not been addressed by the Supreme Court, but occurred in the case of Aldrich Ames.[97]

The law recognizes a distinction between domestic surveillance taking place within U.S. borders and foreign surveillance of non-U.S. persons either in the U.S. or abroad.[98] In United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the principle that the Constitution does not extend protection to non-U.S. persons located outside of the United States, so no warrant was required to engage in even physical searches of non-U.S. citizens abroad.

In 1985 the Supreme Court established the "border search exception", which permits warrantless searches at the US border "or its functional equivalent" in United States v. Montoya De Hernandez, 473 U.S. 531, 538. The US can do so as a sovereign nation to protect its interests. Courts have explicitly included computer hard drives within the exception (United States v. Ickes, 393 F.3d 501 4th Cir. 2005), while United States v. Ramsey, explicitly included all international postal mail.

The Supreme Court has not ruled on the constitutionality of warrantless searches targeting foreign powers or their agents within the US. Multiple Circuit Court rulings uphold the constitutionality of warrantless searches or the admissibility of evidence so obtained.[99] In United States v. Bin Laden, the Second Circuit noted that "no court, prior to FISA, that was faced with the choice, imposed a warrant requirement for foreign intelligence searches undertaken within the United States."[100]

National Security Act of 1947

[edit]The National Security Act of 1947[101] requires Presidential findings for covert acts. SEC. 503. [50 U.S.C. 413b] (a) (5) of that act states: "A finding may not authorize any action that would violate the Constitution or any statute of the United States."

Under § 501–503, codified as 50 USC § 413-§ 413b,[102] the President is required to keep Congressional intelligence committees "fully and currently" informed of U.S. intelligence activities, "consistent with ... protection from unauthorized disclosure of classified information relating to sensitive intelligence sources and methods or other exceptionally sensitive matters." For covert actions, from which intelligence gathering activities are specifically excluded in § 413b(e)(1), the President is specifically permitted to limit reporting to selected Members.[103]

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act

[edit]The 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) regulates government agencies' physical searches and electronic surveillance, in cases wherein a significant purpose is to gather foreign intelligence information. "Foreign intelligence information" is defined in 50 U.S.C. § 1801 as information necessary to protect the U.S. or its allies against actual or potential attack from a foreign power, sabotage or international terrorism. FISA defines a "foreign power" as a foreign government or any faction(s) of a foreign government not substantially composed of US persons, or any entity directed or controlled by a foreign government. FISA provides for both criminal and civil liability for intentional electronic surveillance under color of law except as authorized by statute.

FISA specifies two documents for the authorization of surveillance. First, FISA allows the Justice Department to obtain warrants from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) before or up to 72 hours after the beginning of the surveillance. FISA authorizes a FISC judge to issue a warrant if "there is probable cause to believe that ... the target of the electronic surveillance is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power." 50 U.S.C. § 1805(a)(3). Second, FISA permits the President or his delegate to authorize warrantless surveillance for the collection of foreign intelligence if "there is no substantial likelihood that the surveillance will acquire the contents of any communication to which a United States person is a party". 50 U.S.C. § 1802(a)(1).[104]

In 2002, the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review (Court of Review) met for the first time and issued an opinion (In re: Sealed Case No. 02-001). They noted that all of the Federal courts of appeal had considered the issue and concluded that constitutional power allowed the president to conduct warrantless foreign intelligence surveillance. Furthermore, based on these rulings it "took for granted such power exists" and ruled that under this presumption, "FISA could not encroach on the president's constitutional power."

18 U.S.C. § 2511(2)(f) provides in part that FISA "shall be the exclusive means by which electronic surveillance, as defined in 50 U.S.C. § 1801(f) ... and the intercept of domestic [communications] may be conducted". The statute includes a criminal sanctions subpart 50 U.S.C. § 1809 granting an exception, "unless authorized by statute".

Authorization for the Use of Military Force

[edit]The Authorization for Use of Military Force was passed by Congress shortly after the 9/11 attacks. AUMF was used to justify the Patriot Act and related laws. It explicitly states in Section 2:

(a) IN GENERAL- That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

USA PATRIOT Act

[edit]Section 215 of the PATRIOT act authorized the FBI to subpoena some or all business records from a business record holder using a warrant applied for in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

Terrorist surveillance program

[edit]The legality of surveillance involving US persons and extent of this authorization is the core of this controversy which includes:

- Constitutional issues concerning the separation of powers and the Fourth Amendment immunities

- The program's effectiveness[105] and scope[106]

- The legality of the leaking and publication of classified information and their implications for national security

- Adequacy of FISA as a tool for fighting terrorism

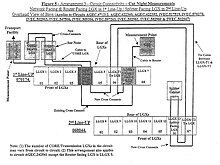

Technical and operational details

[edit]

Because of its highly classified status, the implementation of the TSP is not fairly known by the public. Once Mark Klein, a retired AT&T communications technician, submitted an affidavit describing technical details known to him personally in support of the 2006 Hepting v. AT&T court case.[109][110]

Klein's January 16, 2004 statement included additional details regarding the construction of an NSA monitoring facility in Room 641A of 611 Folsom Street in San Francisco, the site of a large SBC phone building, three floors of which were occupied by AT&T.[111][112]

According to Klein's affidavit, the NSA-equipped room used equipment built by Narus Corporation to intercept and analyze communications traffic, as well as to perform data-mining.[113]

Experts from academia and the computing industry analyzed potential security risks posed by the NSA program, based on Klein's affidavits and those of expert witness J. Scott Marcus, a designer of large-scale IP-based data networks, former CTO at GTE Internetworking and at Genuity, and former senior advisor for Internet Technology at the Federal Communications Commission.[114] They concluded that the likely architecture of the system created serious security risks, including the danger that it could be exploited by unauthorized users, criminally misused by trusted insiders or abused by government agents.[115]

David Addington – at that time legal counsel to former Vice President Dick Cheney – was reported to be the author of the controlling legal and technical documents for the program.[116][117][118]

Legal issues

[edit]While the dispute over the NSA program was waged on multiple fronts, the legal dispute pitted Bush and Obama administrations against opponents in Congress and elsewhere. Supporters claimed that the President's Constitutional duties as commander in chief allowed him to take all necessary steps in wartime to protect the nation and that AUMF activated those powers. Opponents countered by claiming that instead that existing statutes (predominantly FISA) circumscribed those powers, including during wartime.[119]

Formally, the question can be seen as a disagreement over whether Constitutional or statutory law should rule in this case.[120]

As the debate continued, other arguments were advanced.

Constitutional issues

[edit]The constitutional debate surrounding the program is principally about separation of powers. If no "fair reading" of FISA can satisfy the canon of avoidance, these issues must be decided at the appellate level. In such a separation of powers dispute, Congress bears burden of proof to establish its supremacy: the Executive branch enjoys the presumption of authority until an Appellate Court rules against it.[121]

Article I and II

[edit]Whether "proper exercise" of Congressional war powers includes authority to regulate the gathering of foreign intelligence is a historical point of contention between the Executive and Legislative branches. In other rulings [122] has been recognized as "fundamentally incident to the waging of war".[123][21]

"Presidential Authority to Conduct Warrantless Electronic Surveillance to Gather Foreign Intelligence Information",[21] published by The Congressional Research Service stated:

A review of the history of intelligence collection and its regulation by Congress suggests that the two political branches have never quite achieved a meeting of the minds regarding their respective powers. Presidents have long contended that the ability to conduct surveillance for intelligence purposes is a purely executive function, and have tended to make broad assertions of authority while resisting efforts on the part of Congress or the courts to impose restrictions. Congress has asserted itself with respect to domestic surveillance, but has largely left matters involving overseas surveillance to executive self-regulation, subject to congressional oversight and willingness to provide funds.

The same report repeats the Congressional view that intelligence gathered within the U.S. and where "one party is a U.S. person" qualifies as domestic in nature and as such is within their purview to regulate, and further that Congress may "tailor the President's use of an inherent constitutional power":

The passage of FISA and the inclusion of such exclusivity language reflects Congress's view of its authority to cabin the President's use of any inherent constitutional authority with respect to warrantless electronic surveillance to gather foreign intelligence.

The Senate Judiciary Committee articulated its view with respect to congressional power to tailor the President's use of an inherent constitutional power:

- The basis for this legislation [FISA] is the understanding – concurred in by the Attorney General – that even if the President has an "inherent" constitutional power to authorize warrantless surveillance for foreign intelligence purposes, Congress has the power to regulate the exercise of this authority by legislating a reasonable warrant procedure governing foreign intelligence surveillance

Fourth Amendment

[edit]The Bush administration claimed that the administration viewed the unanimity of pre-FISA Circuit Court decisions as vindicating their argument that warrantless foreign-intelligence surveillance authority existed prior to and subsequent to FISA and that this derived its authority from the Executive's inherent Article II powers, which may not be encroached upon by statute.[124]

District Court findings

[edit]Even some legal experts who agreed with the outcome of ACLU v. NSA criticized the opinion's reasoning.[125] Glenn Greenwald argued that the perceived flaws in the opinion in fact reflect the Department of Justice's refusal to argue the legal merits of the program (they focused solely on standing and state secrets grounds).[126]

FISA practicality

[edit]FISA grants FISC the exclusive power to authorize surveillance of US persons as part of foreign intelligence gathering and makes no separate provision for surveillance in wartime. The interpretation of FISA's exclusivity clause is central because both sides agree that the NSA program operated outside FISA. If FISA is the controlling authority, the program is illegal.[127]

The "no constitutional issue" critique is that Congress has the authority to legislate in this area under Article I and the Fourth Amendment,[128] while the "constitutional conflict" critique[129] claims that the delineation between Congressional and Executive authority in this area is unclear,[130] but that FISA's exclusivity clause shows that Congress had established a role for itself in this arena.

The Bush administration argued both that the President had the necessary power based solely on the Constitution and that conforming to FISA was not practical given the circumstances. Assistant Attorney General for Legislative Affairs, William Moschella, wrote:

As explained above, the President determined that it was necessary following September 11 to create an early warning detection system. FISA could not have provided the speed and agility required for the early warning detection system. In addition, any legislative change, other than the AUMF, that the President might have sought specifically to create such an early warning system would have been public and would have tipped off our enemies concerning our intelligence limitations and capabilities.

FBI Special Agent Coleen Rowley, in her capacity as legal counsel to the Minneapolis Field Office[131] recounted how FISA procedural hurdles had hampered the FBI's investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui (the so-called "20th hijacker") prior to the 9/11 attacks. Among the factors she cited were the complexity of the application, the amount of detailed information required, confusion by field operatives about the standard of probable cause required by the FISC and the strength of the required link to a foreign power. At his appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee in June 2002, FBI Director Robert Mueller responded to questions about the Rowley allegations, testifying that unlike normal criminal procedures, FISA warrant applications are "complex and detailed", requiring the intervention of FBI Headquarters (FBIHQ) personnel trained in a specialized procedure (the "Woods" procedure) to ensure accuracy.[132]

The Supreme Court made no ruling on this question. However, on June 29, 2006, in Hamdan, the Supreme Court rejected an analogous argument. Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens, while ruling that "the AUMF activated the President's war powers, and that those powers include the authority to convene military commissions in appropriate circumstances" (citations omitted), held that nothing in the AUMF language expanded or altered the Uniform Code of Military Justice (which governs military commissions.) Stevens distinguished Hamdan from Hamdi (in which AUMF language was found to override the explicit language regarding detention in 18 U.S.C. § 4001(a)) in that Hamdan would require a "Repeal by implication" of the UCMJ.

Authorizing statute

[edit]The Bush administration held that AUMF enables warrantless surveillance because it is an authorizing statute.

An Obama Department of Justice whitepaper interpreted FISA's "except as authorized by statute" clause to mean that Congress allowed for future legislative statute(s) to provide exceptions to the FISA warrant requirements[133] and that the AUMF was such a statute. They further claimed that AUMF implicitly provided executive authority to authorize warrantless surveillance.

This argument is based on AUMF language, specifically, the acknowledgment of the President's Constitutional authority contained in the preamble:

Whereas, the President has authority under the Constitution to take action to deter and prevent acts of international terrorism against the United States ...

and the language in the resolution;

[Be it resolved] [t]hat the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

The Obama administration further claimed that Title II of the USA PATRIOT Act entitled Enhanced Surveillance Procedures also allowed the program,[134] Obama stated that Americans' civil liberties were protected and that purely domestic wiretapping was conducted only pursuant to warrants.[135]

Because FISA authorizes the President to bypass the FISC only during the first 15 days of a war declared by Congress, the argument claimed the AUMF implicitly gave the President the necessary power (as would any Congressional declaration of war). However, as a declaration of war encompasses all military actions so declared, including any otherwise constrained by Congress, the administration held that FISA set a presumptive minimum, which might be extended (explicitly or implicitly) by a declaration.

Corporate confidentiality analysis

[edit]Corporate secrecy is also an issue. In a letter to the EFF, AT&T objected to the filing of the documents in any manner, saying that they contain sensitive trade secrets and could be "used to 'hack' into the AT&T network, compromising its integrity".[136] However, Chief Judge Walker stated, during the September 12, 2008 hearing in the EFF class-action lawsuit, that the Klein evidence could be presented in court, effectively ruling that AT&T's trade secret and security claims were unfounded.

Duty to notify Congress

[edit]The Bush administration contended that with regard to the NSA program, it had fulfilled its notification obligations by briefing key members of Congress (thirteen individuals between the 107th and 109th Congressional sessions) more than a dozen times,[citation needed][137] but they were forbidden from sharing that information with other members or staff.[citation needed]

The CRS report asserted that the specific statutory notification procedure for covert action did not apply to the NSA program. It is not clear whether a restricted notification procedure intended to protect sources and methods was expressly prohibited. Additionally, the sources and methods exception requires a factual determination as to whether it should apply to disclosure of the program itself or only to specific aspects.

Peter J. Wallison, former White House Counsel to President Ronald Reagan stated, "It is true, of course, that a president's failure to report to Congress when he is required to do so by law is a serious matter, but in reality the reporting requirement was a technicality that a President could not be expected to know about."[138]

War Powers Resolution

[edit]The majority of legal arguments supporting the program were based on the War Powers Resolution. The War Powers Resolution has been questioned since its creation, and its application to the NSA program was questioned.

US citizens

[edit]No declaration of war explicitly applied to US citizens. Under the War Powers Resolution the only option to include them was to enact an encompassing authorization of the use of military force. The AUMF did not explicitly do so. Under AUMF, "nations, organizations or persons" must be identified as having planned, authorized, committed, aided or harbored the (9/11) attackers. Military force is thereby limited to those parties. Since no US citizens were alleged to be involved in the 9/11 attacks, and since AUMF strictly states that war-time enemies are those who were involved in 9/11, including US citizens in general exceeds these provisions.

Opinions that actions stemming from the Patriot Act are constitutional follow from the AUMF. Since AUMF wartime powers do not explicitly apply to US citizens in general, they are exempted from its provision as a function of Ninth Amendment unenumerated rights. Therefore, Patriot Act provisions that are unconstitutionally (violating the first, fourth and other amendments) applied to US citizens are not rescued by the AUMF.

Other arguments

[edit]Philip Heymann claimed Bush had misstated the In re: Sealed Case No. 02-001 ruling that supported Congressional regulation of surveillance. Heymann said, "The bottom line is, I know of no electronic surveillance for intelligence purposes since the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act was passed that was not done under the ... statute."[139]

Cole, Epstein, Heynmann, Beth Nolan, Curtis Bradley, Geoffrey Stone, Harold Koh, Kathleen Sullivan, Laurence Tribe, Martin Lederman, Ronald Dworkin, Walter Dellinger, William Sessions and William Van Alstyne wrote, "the Justice Department's defense of what it concedes was secret and warrantless electronic surveillance of persons within the United States fails to identify any plausible legal authority for such surveillance."[140] They summarized:

If the administration felt that FISA was insufficient, the proper course was to seek legislative amendment, as it did with other aspects of FISA in the Patriot Act, and as Congress expressly contemplated when it enacted the wartime wiretap provision in FISA. One of the crucial features of a constitutional democracy is that it is always open to the President—or anyone else—to seek to change the law. But it is also beyond dispute that, in such a democracy, the President cannot simply violate criminal laws behind closed doors because he deems them obsolete or impracticable.

Law school dean Robert Reinstein asserted that the warrantless domestic spying program is[141][142]

a pretty straightforward case where the president is acting illegally. ... When Congress speaks on questions that are domestic in nature, I really can't think of a situation where the president has successfully asserted a constitutional power to supersede that. ... This is domestic surveillance over American citizens for whom there is no evidence or proof that they are involved in any illegal activity, and it is in contravention of a statute of Congress specifically designed to prevent this.

Law professor Robert M. Bloom and William J. Dunn, a former Defense Department intelligence analyst, claimed:[143]

President Bush argues that the surveillance program passes constitutional inquiry based upon his constitutionally delegated war and foreign policy powers, as well as from the congressional joint resolution passed following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. These arguments fail to supersede the explicit and exhaustive statutory framework provided by Congress and amended repeatedly since 2001 for judicial approval and authorization of electronic surveillance. The specific regulation by Congress based upon war powers shared concurrently with the President provides a constitutional requirement that cannot be bypassed or ignored by the President.

Law professor Jordan Paust argued:[144]

any so-called inherent presidential authority to spy on Americans at home (perhaps of the kind denounced in Youngstown (1952) and which no strict constructionist should pretend to recognize), has been clearly limited in the FISA in 18 U.S.C. § 2511(2)(f) and 50 U.S.C. § 1809(a)(1), as supplemented by the criminal provisions in 18 U.S.C. § 2511(1).

Law Dean Harold Koh, Suzanne Spaulding and John Dean contended that FISA was controlling,[145] (in seeming disagreement with the FISC of Review finding) and that the President's admissions constituted sufficient evidence of a violation of the Fourth Amendment, without requiring further factual evidence.

Law professor John C. Eastman compared the CRS and DOJ reports and concluded instead that under the Constitution and ratified by both historical and Supreme Court precedent, "the President clearly has the authority to conduct surveillance of enemy communications in time of war and of the communications to and from those he reasonably believes are affiliated with our enemies. Moreover, it should go without saying that such activities are a fundamental incident of war."[146]

Law professor Orin Kerr argued that the part of In re: Sealed Case No. 02-001 that dealt with FISA (rather than the Fourth Amendment) was nonbinding obiter dicta and that the argument did not restrict Congress's power to regulate the executive in general.[147] Separately Kerr argued for wireless surveillance based on the fact that the border search exception permits searches at the border "or its functional equivalent." (United States v. Montoya De Hernandez, 473 U.S. 531, 538 (1985)). As a sovereign nation the US can inspect goods crossing the border. The ruling interpreted the Fourth Amendment to permit such searches. Courts have applied the border search exception to computers and hard drives, e.g., United States v. Ickes, 393 F.3d 501 (4th Cir. 2005) Case law does not treat data differently than physical objects. Case law applies the exception to international airports and international mail (United States v. Ramsey). Case law is phrased broadly. The exception could analogously apply to monitoring an ISP or telephony provider.[148][149]

U.S. District Judge Dee Benson, who served on the FISC, stated that he was unclear on why the FISC's emergency authority would not meet the administration's stated "need to move quickly".[150][151] The court was also concerned about "whether the administration had misled their court about its sources of information on possible terrorism suspects ... [as this] could taint the integrity of the court's work."[152]

Judge Richard Posner opined that FISA "retains value as a framework for monitoring the communications of known terrorists, but it is hopeless as a framework for detecting terrorists. [FISA] requires that surveillance be conducted pursuant to warrants based on probable cause to believe that the target of surveillance is a terrorist, when the desperate need is to find out who is a terrorist."[153]

Related issues

[edit]Earlier warrantless surveillance

[edit]The Bush administration compared the NSA warrantless surveillance program with historical wartime warrantless searches in the US, going back to the time of the nation's founding.[5]

Critics pointed out that the first warrantless surveillance occurred before the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, and the other historical precedents cited by the administration were before FISA's passage and therefore did not directly contravene federal law.[129] Earlier electronic surveillance by the federal government such as Project SHAMROCK, led to reform legislation in the 1970s.[154] Advancing technology presented novel questions as early as 1985.[155]

Executive orders by previous administrations including Presidents Clinton and Carter authorized their Attorneys General to exercise authority with respect to both options under FISA.[156][157] Clinton's executive order authorized his Attorney General "[pursuant] to section 302(a)(1)" to conduct physical searches without court order "if the Attorney General makes the certifications required by that section".

Unitary Executive theory

[edit]The Unitary Executive theory as interpreted by John Yoo et al., supported the Bush administration's Constitutional argument. He argued that the President had the "inherent authority to conduct warrantless searches to obtain foreign intelligence".[158][159]

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that the President's authority as commander-in-chief extends to the "independent authority to repel aggressive acts ... without specific congressional authorization" and without court review of the "level of force selected".[160] Whether such declarations applying to foreign intelligence are or must be in compliance with FISA has been examined by few courts.

Classified information

[edit]Leaks

[edit]No single law criminalizes the leaking of classified information. Statutes prohibit leaking certain types of classified information under certain circumstances. One such law is ; it was tacked on to the Espionage Act of 1917. It is known as the 'SIGINT' statute, meaning signals intelligence. This statute says:

... whoever knowingly and willfully communicates, furnishes, transmits, or otherwise makes available to an unauthorized person, [including by publication,] classified information [relating to] the communication intelligence activities of the United States or any foreign government, [shall be fined or imprisoned for up to ten years.]

This statute is not limited in application to only federal government employees. However, the Code of Federal Regulations suggests the statute may apply primarily to the "[c]ommunication of classified information by Government officer or employee". 50 USCS § 783 (2005).

A statutory procedure[161] allows a "whistleblower" in the intelligence community to report concerns with the propriety of a secret program. The Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act of 1998, Pub. L. 105–272, Title VII, 112 Stat. 2413 (1998) essentially provides for disclosure to the agency Inspector General, and if the result of that is unsatisfactory, appeal to the Congressional Intelligence Committees. Former NSA official Russ Tice asked to testify under the terms of the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act, in order to provide information to these committees about "highly classified Special Access Programs, or SAPs, that were improperly carried out by both the NSA and the Defense Intelligence Agency".[162]

Executive Order 13292, which sets up the U.S. security classification system, provides (Sec 1.7) that "[i]n no case shall information be classified in order to conceal violations of law".

Given doubts about the legality of the overall program, the classification of its existence may not have been valid under E.O. 13292.[citation needed][163]

Publication of classified information

[edit]It is unlikely that a media outlet could be held liable for publishing classified information under established Supreme Court precedent. In Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514,[164] the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment precluded liability for a media defendant for publication of illegally obtained communications that the media defendant itself did nothing illegal to obtain, if the topic involves a public controversy. Due to the suit's procedural position, the Court accepted that intercepting information that was ultimately broadcast by the defendant was initially illegal (in violation of ECPA), but nonetheless gave the radio station a pass because it did nothing itself illegal to obtain the information.

Nor could the government have prevented the publication of the classified information by obtaining an injunction. In the Pentagon Papers case, (New York Times Co. v. U.S., 403 U.S. 713 (1971)),[165] the Supreme Court held that injunctions against the publication of classified information (United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by The Department of Defense – a 47-volume, 7,000-page, top-secret United States Department of Defense history of the United States' involvement in the Vietnam War) were unconstitutional prior restraints and that the government had not met the heavy burden of proof required for prior restraint.

The 1917 Espionage Act, aside from the SIGINT provision discussed above, only criminalizes 'national defense' information, not 'classified' information. Although the Justice Department as a matter of law sees no exemption for the press, as a matter of fact it has refrained from prosecuting:

A prosecution under the espionage laws of an actual member of the press for publishing classified information leaked to it by a government source would raise legitimate and serious issues and would not be undertaken lightly, indeed, the fact that there has never been such a prosecution speaks for itself.

On the other hand, Sean McGahan of Northeastern University stated,

There's a tone of gleeful relish in the way they talk about dragging reporters before grand juries, their appetite for withholding information, and the hints that reporters who look too hard into the public's business risk being branded traitors.[166]

Responses and analyses

[edit]Administration response to press coverage

[edit]On December 17, 2005, President Bush addressed the growing controversy in his weekly radio broadcast.[167] He stated that he was using his authority as President, as Commander in Chief and such authority as the Congress had given him, to intercept international communications of "people with known links to al Qaeda and related terrorist organizations". He added that before intercepting any communications, "the government must have information that establishes a clear link to these terrorist networks." He speculated that had the right communications been intercepted, perhaps the 9/11 attacks could have been prevented. He said the NSA program was re-authorized every 45 days, having at that time been reauthorized "more than 30 times"; it was reviewed by DOJ and NSA lawyers "including NSA's general counsel and inspector general", and Congress leaders had been briefed "more than a dozen times".[168]

In a speech in Buffalo, New York on April 20, 2004, he said that:

Secondly, there are such things as roving wiretaps. Now, by the way, any time you hear the United States government talking about wiretap, it requires – a wiretap requires a court order. Nothing has changed, by the way. When we're talking about chasing down terrorists, we're talking about getting a court order before we do so. It's important for our fellow citizens to understand, when you think Patriot Act, constitutional guarantees are in place when it comes to doing what is necessary to protect our homeland, because we value the Constitution.[169]

And again, during a speech at Kansas State University on January 23, 2006, President Bush mentioned the program, and added that it was "what I would call a terrorist surveillance program", intended to "best ... use information to protect the American people",[170] and that:

What I'm talking about is the intercept of certain communications emanating between somebody inside the United States and outside the United States; and one of the numbers would be reasonably suspected to be an al Qaeda link or affiliate. In other words, we have ways to determine whether or not someone can be an al Qaeda affiliate or al Qaeda. And if they're making a phone call in the United States, it seems like to me we want to know why. This is a – I repeat to you, even though you hear words, "domestic spying," these are not phone calls within the United States. It's a phone call of an al Qaeda, known al Qaeda suspect, making a phone call into the United States ... I told you it's a different kind of war with a different kind of enemy. If they're making phone calls into the United States, we need to know why – to protect you.

During a speech[171] in New York on January 19, 2006 Vice President Cheney commented on the controversy, stating that a "vital requirement in the war on terror is that we use whatever means are appropriate to try to find out the intentions of the enemy," that complacency towards further attack was dangerous, and that the lack of another major attack since 2001 was due to "round the clock efforts" and "decisive policies", and "more than luck." He stated:

[B]ecause you frequently hear this called a 'domestic surveillance program.' It is not. We are talking about international communications, one end of which we have reason to believe is related to al Qaeda or to terrorist networks affiliated with al Qaeda.. a wartime measure, limited in scope to surveillance associated with terrorists, and conducted in a way that safeguards the civil liberties of our people.

In a press conference on December 19 held by both Attorney General Gonzales and General Michael Hayden, the Principal Deputy Director for National Intelligence, General Hayden claimed, "This program has been successful in detecting and preventing attacks inside the United States." He stated that even an emergency authorization under FISA required marshaling arguments and "looping paperwork around". Hayden implied that decisions on whom to intercept under the wiretapping program were being made on the spot by a shift supervisor and another person, but refused to discuss details of the specific requirements for speed.[19]

Beginning in mid-January 2006 public discussion increased on the legality of the terrorist surveillance program.[172]

DOJ sent a 42-page white paper to Congress on January 19, 2006 stating the grounds upon which it was felt the NSA program was legal, which restated and elaborated on reasoning Gonzales used at the December press conference.[173] Gonzales spoke again on January 24, claiming that Congress had given the President the authority to order surveillance without going through the courts, and that normal procedures to order surveillance were too slow and cumbersome.[174]

General Hayden stressed the NSA's respect for the Fourth Amendment, stating at the National Press Club on January 23, 2006, "Had this program been in effect prior to 9/11, it is my professional judgment that we would have detected some of the 9/11 al Qaeda operatives in the United States, and we would have identified them as such."[175]

In a speech on January 25, 2006, President Bush said, "I have the authority, both from the Constitution and the Congress, to undertake this vital program,"[176] telling the House Republican Caucus at their February 10 conference in Maryland that "I wake up every morning thinking about a future attack, and therefore, a lot of my thinking, and a lot of the decisions I make are based upon the attack that hurt us."[177]

President Bush reacted to a May 10 domestic call records article by restating his position, that it is "not mining or trolling through the personal lives of millions of innocent Americans".[178]

Congressional response

[edit]Three days after news broke about the NSA program, a bipartisan group of Senators—Democrats Dianne Feinstein, Carl Levin, Ron Wyden and Republicans Chuck Hagel and Olympia Snowe, wrote to the Judiciary and Intelligence Committee chairs and ranking members requesting the two committees to "seek to answer the factual and legal questions" about the program.

On January 20, 2006, in response to the administration's asserted claim to base the NSA program in part on the AUMF, Senators Leahy and Kennedy introduced Senate Resolution 350 that purported to express a "sense of the Senate" that the AUMF "does not authorize warrantless domestic surveillance of United States citizens".[38][39] It was not reported out of committee.[40]

In introducing their resolution to committee,[179] they quoted Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's opinion that even war "is not a blank check for the President when it comes to the rights of the Nation's citizens".

Additionally, they asserted that the DOJ legal justification was a "manipulation of the law" similar to other "overreaching" and "twisted interpretations" in recent times. Leahy and Kennedy also asserted that Gonzales had "admitted" at a press conference on December 19, 2005, that the Administration did not seek to amend FISA to authorize the NSA spying program because it was advised that "it was not something we could likely get." (However, as noted below under "Proposed Amendments to FISA", Gonzales made clear that what he actually said was that such an amendment was "not something [they] could likely get" without disclosing the nature of the program and operational limitations and that it was believed that such disclosure would be damaging to national security.)

Leahy and Kennedy asserted that the procedures adopted for the NSA program, specifically the 45-day reapproval cycle was "not good enough" because the review group were executive branch appointees. Finally, they concluded that Congressional and Judicial oversight were fundamental and should not be unilaterally discarded.

In February 2008, the Bush administration backed a new version of FISA that would grant telecom companies retroactive immunity from lawsuits stemming from surveillance. On March 14, the House passed a bill that did not grant such immunity.

Anonymity networks

[edit]Edward Snowden copied and leaked thousands of classified NSA documents to journalists. The information revealed the access of some federal agencies to the public's online identity and led to wider use anonymizing technologies. In late 2013, soon after Snowden's leaks, it was loosely calculated that encrypted browsing software, such as Tor, I2P and Freenet had "combined to more than double in size ... and approximately 1,050,000 total machines 'legitimately' use the networks on a daily basis, amounting to an anonymous population that is about 0.011 percent of all machines currently connected to the Internet."[180] Given that these tools are designed to protect the identity and privacy of their users, an exact calculation of the growth of the anonymous population cannot be accurately rendered, but all estimates predict rapid growth.

These networks were accused of supporting illegal activity. They can be used for the illicit trade of drugs, guns and pornography. However, Tor executive director Roger Dingledine claimed that the "hidden services" represent only 2 percent of total traffic on Tor's network.[181] This fact suggests that the large majority of those who use it do so in order to protect their normal browsing activity, an effort to protect their personal values of privacy rather than to participate in illegal activity.

Trade-off between security and liberty

[edit]Polls analyzed the trade-off between security and liberty. A June 2015 poll conducted by Gallup asked participants if the US should take all the necessary steps to prevent terrorist attacks even if civil liberties are violated. 30% of respondents agreed: 65% instead said take steps, but do not violate civil liberties.[182]

In a 2004 Pew poll, 60% of respondents rejected the idea of sacrificing privacy and freedom in the name of security.[183] By 2014 a similar Pew poll found that 74% of respondents preferred privacy, while 22% said the opposite. Pew noted that post 9/11 surveys revealed that in the periods during which prominent incidents that related to privacy and security first came up, the majority of respondents favored an ideology of "security first", while maintaining that a dramatic reduction in civil liberties should be avoided. Events often caused Americans to back allow government to investigate suspected terrorists more effectively, even if those steps might infringe on the privacy of ordinary citizens. The majority of respondents reject steps that translate into extreme intrusion into their lives.[184]

Various administrations claimed that reducing privacy protections reduces obstacles that anti-terrorism agencies face attempting to foil terrorist attacks and that fewer privacy protections makes it more difficult for terrorist groups to operate.[185]

See also

[edit]- Clapper v. Amnesty International – 2013 Supreme Court decision

- Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act

- Criticism of the War on Terror

- Data mining

- Deep packet inspection

- ECHELON

- Edward Snowden

- Electronic Privacy Information Center v. Department of Justice

- Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act

- General Michael Hayden

- Global surveillance disclosures (1970–2013)

- Global surveillance whistleblowers

- Hepting v. AT&T

- HTLINGUAL – a CIA project to intercept mail destined for the Soviet Union and China that operated from 1952 until 1973.

- Information Awareness Office

- In the First Circle, Alexander Solzhenytsin

- Mark Riebling

- Mass surveillance

- NSA call database

- NSA wiretapping programs

- Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968

- PRISM – the program that replaced the warrantless surveillance program

- Reichstag Fire Decree

- Room 641A

- Secure communication

- Terrorist Surveillance Program – details of the program itself

- Trailblazer Project

References

[edit]- ^ Sanger, David E.; O'Neil, John (January 23, 2006). "White House Begins New Effort to Defend Surveillance Program". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Gonzales_Letter" (PDF). The New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 20, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ Savage, Charlie; Risen, James (March 31, 2010). "Federal Judge Finds N.S.A. Wiretaps Were Illegal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Eric Lichtblau and James Risen (April 15, 2009). "Officials Say U.S. Wiretaps Exceeded Law". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "Prepared Statement of Hon. Alberto R. Gonzales, Attorney General of the United States" (Press release). US Department of Justice. February 6, 2006.

- ^ Banks, Christopher P. (January 1, 2010). "Security and Freedom After September 11". Public Integrity. 13 (1): 5–24. doi:10.2753/pin1099-9922130101. ISSN 1099-9922. S2CID 141765924.

- ^ James Risen & Eric Lichtblau (December 21, 2005). "Spying Program Snared U.S. Calls". The New York Times. Retrieved May 28, 2006.

- ^ "AT&T's Role in Dragnet Surveillance of Millions of Its Customers" (PDF). EFF.

- ^ "US CODE: Title 50, section 1809. Criminal sanctions".

- ^ "US CODE: Title 18, section 2511. Interception and disclosure of wire, oral, or electronic communications prohibited".

- ^ James Risen & Eric Lichtblau (December 16, 2005). "Bush Lets U.S. Spy on Callers Without Courts". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ "Bush Lets U.S. Spy on Callers Without Courts". NYT's Risen & Lichtblau's December 16, 2005 Bush Lets U.S. Spy on Callers Without Courts. Archived from the original on February 6, 2006. Retrieved February 18, 2006. via commondreams.org

- ^ Calame, Byron (August 13, 2006). "Eavesdropping and the Election: An Answer on the Question of Timing". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric (March 26, 2008). "The Education of a 9/11 Reporter: The inside drama behind the Times' warrantless wiretapping story". Slate. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ Grieve, Tim (August 14, 2006). "What the Times knew, and when it knew it". Salon. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (December 13, 2008). "The Fed Who Blew the Whistle". Newsweek. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

- ^ Scott Shane (June 11, 2010). "Obama Takes a Hard Line Against Leaks to Press". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (February 19, 2006). "NSA legal arguments". Glenngreenwald.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Press Briefing by Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and General Michael Hayden, Principal Deputy Director for National Intelligence" (Press release). The White House. December 19, 2005. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ "Debate on warrantless wiretapping legality". Archived from the original on January 29, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Presidential Authority to Conduct Warrantless Electronic Surveillance to Gather Foreign Intelligence Information" (PDF) (Press release). Congressional Research Service. January 5, 2006.

- ^ Eggen, Dan (January 19, 2006). "Congressional Agency Questions Legality of Wiretaps". The Washington Post. pp. A05. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2017.