Wages for housework

The International Wages for Housework Campaign (IWFHC) is a grassroots women's network campaigning for recognition and payment for all caring work, in the home and outside. It was started in 1972 by Mariarosa Dalla Costa,[1] Silvia Federici,[2] Brigitte Galtier, and Selma James[3] who first put forward the demand for wages for housework. At the third National Women's Liberation Conference in Manchester, England, the IWFHC states that they begin with those with least power internationally – unwaged workers in the home (mothers, housewives, domestic workers denied pay), and unwaged subsistence farmers and workers on the land and in the community. They consider the demand for wages for unwaged caring work to be also a perspective and a way of organizing from the bottom up, of autonomous sectors working together to end the power relations among them.

History

[edit]Creation: 1970s

[edit]Wages for housework was one of the six demands in Women, the Unions and Work or What Is Not to Be Done,[4] which James presented as a paper to the third National Women's Liberation Conference. The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community,[5] which James co-authored with Mariarosa Dalla Costa, which opened the "domestic labour debate" and became a women's movement classic, was published soon after Women, the Unions and Work. The first edition of Power of Women did not come out for wages for housework; its third edition, in 1975, did.

After the Manchester conference, James with three or four other women formed the Power of Women Collective in London and Bristol to campaign for wages for housework. It was reconstituted as the Wages for Housework Campaign in 1975, based in London, Bristol, Cambridge and later Manchester.[6]

In 1974, the Wages for Housework Campaign started in Italy. A number of groups calling themselves Salario al Lavoro Domestico (Wages for Housework) formed in various Italian cities. To celebrate, one of the founding members, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, gave a speech entitled "A General Strike" in Mestre, Italy. In this speech she talks about how no strike before has ever been a general strike before, but instead, only a strike for male workers. In Padua, Italy, a group called Lotta Feminista, formed by Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Silvia Federici, adopted the idea of Wages for Housework.[7][8][9]

Between 1974 and 1976, three autonomous organizations formed within the Wages for Housework Campaign in the UK, US and Canada: Wages Due Lesbians (now Queer Strike), the English Collective of Prostitutes and Black Women for Wages for Housework, co-founded by Margaret Prescod (now Women of Colour in the Global Women's Strike).[10][11][12][13] Black Women for Wages for Housework focused on specific issues of Black and third world women, including calling for reparations for "slavery, imperialism and neo-colonialism,". Wages Due Lesbians called for wages for housework and wanted lesbians included in those wages so that it did not exclusively go to "normal women" and for "the additional physical and emotional housework of surviving in a hostile and prejudiced society, recognized as work and paid for so all women have the economic power to afford sexual choices,".[11] Wages Due Lesbians also worked alongside The Lesbian Mothers' National Defense Fund, founded in 1974 and based in Seattle, which aimed to help lesbian mothers who had to fight custody cases after coming out.[14][15] In 1984 WinVisible (women with visible and invisible disabilities) was founded in the UK as an autonomous organisation within the IWFHC.[16][17]

The Women of the World Are Serving Notice!

We want wages for

every dirty toilet

every indecent assault

every painful childbirth

every cup of coffee

and every smile

and if we don't get

what we want we

will simply refuse

to work any longer!

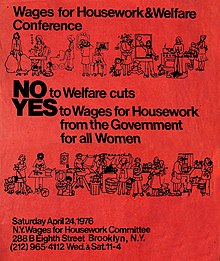

In 1975 Silvia Federici started the New York group called the "Wages for Housework Committee" and opened an office in Brooklyn, New York at 288 B. 8th St. Flyers handed out in support of the New York Wages for Housework Committee called for all women to join regardless of marital status, nationality, sexual orientation, number of children, or employment. In 1975 Federici published Wages Against Housework, the book most commonly associated with the wages for housework movement.[18][19][20]

Men who agree with the WFH perspective formed their own organisation in the mid-70s. It is called Payday men's network and works closely with IWFHC and the Global Women's Strike in London and Philadelphia especially and is active with conscientious objectors and refuseniks in a number of countries. In 1977, two years after Black Women for Wages for Housework was formed in New York there was a split. The WFH group in New York which Silvia Federici had formed dissolved in 1977. [citation needed] The Italian Padua group led by Dalla Costa, who was close to Federici, left the IWFHC and dissolved not long after. Dalla Costa has blamed the political repression in Italy in the late 70s for the dissolution of the Italian WFH groups.

Black Women for Wages for Housework carried on in New York and in London (a group had also started in Bristol in 1976, and later branches formed in Los Angeles and San Francisco). It had a major success at the first congressionally mandated women's conference in Houston, Texas, in 1977. Working with Beulah Sanders and Johnnie Tillmon, the Black women who led the National Welfare Rights Organization, they got the conference to agree that "welfare payments" should be called a "wage". They believe that this helped to delay welfare cuts by 20 years.

IWFHC had an anti-war and anti-militarist perspective from the start, and called for the funds to pay for unwaged caring work to come from military budgets. In England the organization was part of the women's movement against nuclear weapons at Greenham Common and against the building of a new nuclear power reactor at Hinkley (publication Refusing Nuclear Housework).

The U.S. PROStitutes Collective (US PROS) first started in New York in 1982 and later moved to San Francisco and Los Angeles.[21] It campaigns for decriminalization of sex work and for resources so women, children and men are not forced into prostitution. Ruth Todasco, who started the Wages for Housework Campaign in Tulsa, later founded the No Bad Women, Just Bad Laws Coalition which focused on the decriminalization of sex work.[22]

1980s, 1990s

[edit]Throughout the 80s and 90s, the IWFHC representing a number of countries of the Global South and Global North, lobbied the United Nations Conferences on Women on unwaged work. They succeeded in getting the UN to pass path-breaking resolutions that recognized the unwaged caring work that women do in the home, on the land and in the community. They also highlighted the environmental racism that fell on communities of colour and low-income communities generally, bringing together women from the Global South and the Global North who were leading movements against pollution and destruction caused by the military and multinationals.

In 1999 the IWFHC called a global women's strike after Irish women asked for support for a national strike in Ireland to mark the first International Women's Day of the new millennium. Since 8 March 2000, the IWFHC has become more widely known as the Global Women's Strike (GWS), which it co-ordinates from the Crossroads Women's Centre in London, England. There are GWS co-ordinations in India, Ireland, Peru, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago, and close collaboration with Haiti and other countries.

Silvia Federici and several others from the early campaign have continued to publish books and articles related to the demands of Wages for Housework.

The Wages for Housework Campaign called for a Global Women's Strike (GWS) on March 8, 2000, demanding among other things, "Payment for all caring work – in wages, pensions, land and other resources."[23] Women from more than 60 countries around the world participated in the protest.[24] Since 2000 the GWS network has continued the call for a living wage for women and other caregivers, and they have led or joined campaigns focused on pay equity, violence against women, and sex workers' rights, among other issues.

2000s, 2010s

[edit]In 2019 the Global Women's Strike (GWS) network and Wages for Housework Campaign joined a coalition of organizations calling for a Green New Deal for Europe (GNDE).[25] Wages for Housework Campaign co-founder Selma James (with other GWS members) contributed to the GNDE platform report which includes a policy recommendation to "fund a care income to compensate unpaid activities like care for people, the urban environment, and the natural world."[26] The idea of a "care income" expands the original demand for wages for housework to include all indispensable yet unpaid (or underpaid) work that involves caring for people and the planet, or caring for life.

2020s

[edit]On 9 April 2020, in response to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic and the climate emergency, the Global Women's Strike and Women of Colour GWS networks released an open letter to governments amplifying their call for a "care income."[27]

In December 2020, Nadia Oleszczuk of the Consultative Council formed in Poland during the October–November 2020 Polish protests stated that the Council was considering wages for housework as one of its legislative demands.[28]

In 2021 a new civil code came into effect in China, which declares that a spouse can request compensation in a divorce if they have more responsibility than their spouse for caring for elderly relatives, childcare, and/or assisting their spouse in their work.[29][30] Specifically, Article 1088 of the Civil Code states that "Where one spouse is burdened with additional duties for raising children, looking after the elderly or assisting the other spouse in his/her work, the said spouse has the right to request compensation upon divorce against the other party".[30] In a landmark case in 2021, a Beijing district court ruled that a man (known publicly by his surname Chen) must compensate his former wife (known publicly by her surname Wang) for the housework she did while they were married; she was granted compensation of 50,000 yuan ($7,700; £5,460) for five years of unpaid labor.[29]

Relation with Global Women's Strike

[edit]IWFHC and the Global Women's Strike, present themselves as the collective endeavour of the autonomous organizations formed since 1974 and their campaigns. These campaigns include: ending poverty, welfare cuts, detention, deportation; a living wage/care income for mothers and other carers; domestic workers' rights'; pay equity; justice for survivors of rape and domestic violence; challenging racism, disability racism, queer discrimination, transphobia; decriminalizing sex work; stopping the state taking children from their mothers; opposing apartheid, war, genocide, military occupation, corporate land grabs; supporting human rights defenders and refuseniks; ending the death penalty and solitary confinement . . . . All are fighting for climate justice and survival. They describe anti-racism, anti-discrimination, and the justice work women do collectively for themselves and others as being at the heart of all their campaigning.[citation needed]

Controversies

[edit]Critics have argued that providing wages for housework could further reinforce or institutionalize specific gendered roles vis-à-vis housework, and care work more broadly. Rather than providing wages for housework, they argue, the goal should be liberation from it and the demeaning and subordinating role of "housewife". Instead feminists should focus on increasing women's opportunities in the paid workforce with pay equity, while promoting a more equal distribution of unpaid work in the household. Proponents of Wages for Housework also support equal opportunity and pay equity, however, they argue that entering the workforce does not sufficiently challenge the social role of women in the household nor result in a more equitable distribution of unpaid care work. In fact, more often than not, women who have entered the paid workforce often face a "double shift" of work, the first paid work in the labor market and the second unpaid housework.[31] According to one global estimate, women spend 4.5 hours of unpaid work per day, twice as many hours as men do on average.[32]

Other criticisms include the concern that providing wages for housework would commodify intimate human relationships of love and care and would subsume them into capitalist relations. However, proponents of wages for housework contest this "reductive view" of their proposal. For instance, according to Silvia Federici the demand for wages for housework is not just about remuneration for unpaid work or women's financial empowerment and independence. Rather, it is also a political perspective and a revolutionary strategy to make invisible work more visible, to demystify and disrupt the structural reliance of capitalism on the unpaid work of (mostly) women, and to subvert the supposed natural social role of "housewife" that capital has invented for women.[31]

The payment of wages for housework would also require capital to pay for the immense amount of unpaid care work (undertaken largely by women) that currently reproduces the labor force. According to a report by Oxfam and the Institute for Women's Policy Research, the monetary value of unpaid care work is estimated at nearly $11 trillion a year.[33][34] This amounts to an enormous subsidy to the capitalist economy, and paying for it would likely render the current system uneconomic, subverting the social relations in the process.

Monetary estimates of this kind are used to demonstrate the scale of unpaid work in relation to more visible waged work. However, proponents of wages for housework do not advocate for the marketization and commodification of unpaid care work. Instead they have promoted public funding for these schemes as part of a larger project of recognizing and revaluing the indispensable role of unpaid care work for society and the economy. Some feminist scholars have also called for the creation of new commons-based systems of care and basic provisioning that operate outside of the market and state, and for the defense of existing commons, especially in communities of the Global South.[35]

Early influences

[edit]A number of early feminists focused women's economic independence along with the role of housewife in relation to women's oppression. In 1898 Charlotte Perkins Gilman published Women and Economics. This book argued for paid housework 74 years before the International Wages for Housework Campaign was founded as well as arguing to expand the definition of women in the home.[36] She asserts that "wives, as earners through domestic service, are entitled to the wages of cooks, housemaids, nursemaids, seamstresses, or housekeepers" and that providing women economic independence is key to their liberation. Alva Myrdal, a Swedish feminist, focused on state sponsored child care and housing, in order to ease the burden of parenting off mothers.[37] In Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex, in which de Beauvoir asserts that women cannot find transcendence through unpaid house work.[37] This idea is echoed in The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan when she discusses how women are unable to feel fulfilled in the home. The Feminine Mystique defined many second-wave feminist goals, and the connection between the Wages for Housework Campaign and this work cannot be overlooked.[37]

In 1965 Alison Ravetz published "Modern Technology and an Ancient Occupation: Housework in Present-Day Society"[38] which critiques housework being a womanly duty post-Industrial Revolution. The idea here is that since housework has become less labor-intensive since then, it is even less fulfilling than ever before. This echoes a similar argument made by Alva Myrdal.

Perhaps the most important early influence for the modern Wages for Housework Campaign is the work of Eleanor Rathbone, the Independent feminist MP[39] who campaigned for decades for mothers to have an independent income in recognition of their work bringing up children.[40] She saw this as essential to end mothers' and children's poverty and their dependency on a male wage. She laid out her case in her 1924 publication, The Disinherited Family (republished by Falling Wall Press in 1986). Her 25-year-campaign in and out of Parliament won Family Allowance for all mothers in the UK, and was the first measure of the 1945 Welfare State.

Publications

[edit]- Selma James, foreword by Marcus Rediker, introduction by Nina Lopez. Sex, Race and Class – The Perspective of Winning a Selection of Writings 1952–2011. PM Press. 2012 Selma James

- Louise Toupin. Le salaire au travail ménager. Chronique d'une lutte féministe internationale (1972–1977) Éditions du Remue-Ménage, 2014.

- Silvia Federici. Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle. PM Press, 2012.

- Silvia Federici. Wages Against Housework. Published jointly by the Power of Women Collective and Falling Wall Press, 1975. Link goes to full text of the book.

- Cox, Nicole, and Silvia Federici. Counter-planning from the kitchen: wages for housework : a perspective on capital and the Left, New York: New York Wages for Housework Committee. 1976.

- Galimberti, Jacopo (6 September 2022). Images of Class. Operaismo, Autonomia and the Visual Arts (1962-1988). Verso Books . ISBN 978-1-8397-6531-5.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dalla Costa, M. & James, S. (1972). The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community[1]

- ^ Cox, N. & Federici, S. (1975).[2]Counter-Planning from the Kitchen: Wages for Housework a Perspective on Capital and the Left.

- ^ Gardiner, B. (2012). A Life in Writing. Interview with Selma James.

- ^ "Women, the Unions and Work or...What is Not to be Done and the Perspective of Winning". www.akpress.org. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Costa, Mariarosa Dalla; James, Selma (2017). The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 79–86. doi:10.1002/9781119395485.ch7. ISBN 978-1-119-39548-5. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "The Campaign for Wages for Housework" (PDF). bcrw.barnard.edu. Barnard Center for Research on Women. 1975. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ Dalla Costa, Mariarosa (21 October 2010). "A General Strike".

- ^ "More Smiles, More Money", N+1 Magazine, August 2013.

- ^ Tronti, Mario (1962). "Factory and Society". Operaismo in English. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Hendrix, Kathleen (May 1987). "Waging the War Over Wages: Fight for Homemaker Pay has Seen Ups, Downs". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ a b "The International Wages for Housework Campaign" (PDF). Freedomarchives.org. The Freedom Archives. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Hendrix, Kathleen (28 July 1985). "Campaign Catches On: L.A. Pair Seek Wages for Women's Unpaid Work". Newspaper. Retrieved 22 October 2015 – via Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Love, Barbara (2006). Feminists Who Changed America, 1963–1975. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 368. ISBN 978-0252031892.

- ^ Myers, JoAnne (2009). The A to Z of the Lesbian Liberation Movement: Still the Rage. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. pp. xxxvi. ISBN 978-0810863279.

- ^ "The Lesbian Mothers National Defense Fund, the 1970s through 1990s". outhistory.org. Out History. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Tribunal victory gives hope to 'failure to attend' benefit victims". Disability News Service. 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ "Written evidence submitted by WinVisible (COV0106)". WinVisible. 2020-05-01. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Vishmidt, Marina (March 2013). "Permanent Reproductive Crisis: An Interview with Silvia Federici". Meta Mute. Mute.

- ^ Vishmidt, Marina (March 2013). "Permanent Reproductive Crisis: An Interview with Silvia Federici". Meta Mute.

- ^ "A brief history : From Wages for Housework to Global Women's Strike". Global Women's Strike. 6 March 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "US PROS Collective". US PROS Collective. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Overs, Cheryl (2012). "'No Bad Women, Just Bad Laws': Three Decades of Sex Work Law Reform Advocacy" (PDF). HIV and the Law. Criminalize Hate Not HIV. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ James, Selma (8 March 2018). "Decades after Iceland's 'day off', our women's strike is stronger than ever | Selma James". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Guardian Staff (7 March 2000). "Stop the world and change it: the global women's strike". the Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Green New Deal for Europe". Green New Deal for Europe. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "A Blueprint for Europe's Just Transition". Green New Deal for Europe. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "PRESS STATEMENT: In response to Covid-19 and the climate emergency: organizations around the world call for a Care Income Now! – GLOBAL WOMEN'S STRIKE / WAGES FOR HOUSEWORK / SELMA JAMES". 9 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Kobylańska, Joanna (2020-12-01). "Nadia Oleszczuk z kolejnym postulatem. Mówi o krótszym dniu pracy dla kobiet" [Nadia Oleszczuk with another demand. She talks about a shorter working day for women]. Wirtualna Polska (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- ^ a b "China court orders man to pay wife for housework in landmark case". BBC News. 24 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Woman gets compensation for housework in Chinese divorce ruling". NBC News. 24 February 2021.

- ^ Gupta, Alisha Haridasani (23 January 2020). "Women, Burdened With Unpaid Labor, Bear Brunt of Global Inequality". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-01-24. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Wezerek, Gus; Ghodsee, Kristen R. (5 March 2020). "Opinion | Women's Unpaid Labor is Worth $10,900,000,000,000". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Time to Care". www.oxfamamerica.org. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Feminism and the Politics of the Commons | The Wealth of the Commons". wealthofthecommons.org. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Perkins Gilman, Charlotte (1898). Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution. United States: Small, Maynard & Company.

- ^ a b c Freedman, Estelle (2007). The Essential Feminist Reader. Modern Library. ISBN 9780812974607.

- ^ Ravetz, Alison (1965). "Modern Technology and an Ancient Occupation: Housework in Present-Day Society". Technology and Culture. 6 (2): 256–260. doi:10.2307/3101078. JSTOR 3101078. S2CID 112327602.

- ^ Reeves, Rachel (8 March 2019). "Eleanor Rathbone, the forgotten MP who changed women's lives by pioneering child benefits". inews.

- ^ James, Selma (6 August 2016). "Child benefit has been changing lives for 70 years. Let's not forget the woman behind it". The Guardian.

External links

[edit]- Selma James and the Wages for Housework Campaign - article by Shemon Salam in New Beginnings, a journal of independent labour

- "Women in the Workforce" collections. Barnard Archive.

- Global Women's Strike/ Wages For Housework/ Selma James website

- Green New Deal for Europe campaign website