Viktor Perelman

Viktor Borisovich Perelman | |

|---|---|

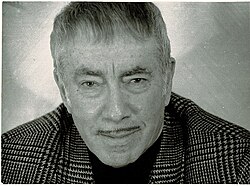

Viktor Perelman in 2000 celebrating the 25th anniversary of his 'Vrema I My' magazine | |

| Native name | Виктор Борисович Перельман |

| Born | July 15, 1929 Moscow, Russia |

| Died | November 13, 2003 (aged 74) New Jersey, United States |

| Pen name | Viktor Perelman, Viktor Petrovsky, Viktor Aleksandrovsky |

| Occupation | writer, journalist, publisher, editor, and dissident |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | American, Russian Jewish, Israeli |

| Years active | 1952–2001 |

| Notable works | Editor-in-chief of 'Time and We' magazine (1975–2001), 'Forsaken Russia' (1977), 'Theatre of the Absurd' (1984), 'Forsaken Russia: Journalist in a Closed Society' (1989) |

| Notable awards | Second Prize for Dissident Literature in Translation from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel |

| Spouse | Alla Abramovna Svet (m. 1961, his death) |

| Children | Irina Perelman-Grabois |

| Website | |

| viktorperelman-timeandwejournal | |

Viktor Borisovich Perelman (Russian: Виктор Борисович Перельман) (July 15, 1929 – November 13, 2003), was a Russian-language journalist,[1] writer,[2] publisher,[3] editor,[4][5] and dissident.[6] He was the founder and sole editor-in-chief of a leading third wave Russian immigration international democratic journal for literary and social problems, "Time and We" or "Vremya I My" (Russian: "Время и Мы") from 1975 to 2001.[7][5] In addition, he was the author of two autobiographical novels,[8][9] one fiction novel,[10] and dozens of published articles in leading Russian language newspapers and other press.[11] As the founder of Time and We Publishing House, he published several Russian language books by well-known authors of third wave Russian immigration.[3]

Biography

[edit]Viktor Perelman was born on July 15, 1929, in Moscow, Russia (then Russian SFSR, Soviet Union).

In 1951, he graduated with a degree from Moscow State University Faculty of Law (Russian: МГУ) and obtained a Publishing and Editing degree from the Moscow Polygraphic Institute Faculty of Journalism (now known as the Moscow State University of Printing Arts).

In the 1950s, he worked at Radio Moscow, at the newspaper "Trud" (Russian: Труд),[12] was the head of the Economics division of the magazine "Soviet Trade Unions" (Russian: Cоветские Профсоюзы), at "Moskovskij Komsomolets" (Russian: Московский Комсомолец),[13] "Sovietskaya Rossiya" (Russian: Советская Россия), and "Pravda" (Russian: Правда).

In 1968, he was invited to take on the position of the Head of Information Department of "Literaturnaya Gazeta" (Russian: Литературная Газета).[14][15] He was dismissed from the "Literaturnaya Gazeta" following his application for permission to emigrate to Israel in 1972.[16] His dissident articles, among them "Reflections Before the Auction," which described his opposition to the Soviet Government imposing an education tax on Jewish emigrants, were translated and published in Western newspapers, including the New York Times.[17]

After a struggle with Soviet authorities as a Jewish "Refusenik", he was allowed by the Soviet government to emigrate to Israel in 1973,[18] where he worked as a correspondent for the Israeli newspaper "Al Hamishmar",[19] and a special correspondent for Radio Liberty (Russian: Радио Свобода).[20]

In 1975, in Tel Aviv, Israel, he founded a thick Russian language magazine for literary and socio-political problems, "Vremya I My" or "Time and We" (Russian: Время и Мы).[21] He was the magazine's sole editor-in-chief until 2001. He published altogether 152 issues of "Vremya I My",[7] giving a tribune to over 2200 authors and over 100 artists. "Vremya I My" had headquarters in Israel,[22] France,[3] Russia (in its later years),[23] with its main office located in the United States since 1981. Over 150 Slavic Departments of universities around the globe were subscribed to “Time and We” magazine over the 25 years of its existence, with a full archive of 152 issues still available in their library catalogs today.[24][25] The full archive is also available at the library of the National Endowment for Democracy, an organization from which 'Time and We' had been receiving a grant for over 10 years. A full electronic archive of 152 issues of "Time and We" is also available on the electronic library "ImWerden".[7] Viktor Perelman published works by many literary figures of the Russian diaspora,[26] such as poet Alexander Galich,[27] and writers Viktor Nekrasov,[28] Boris Khazanov, and Friedrich Gorenstein.[29] Perelman wrote over 50 essays[30] in "Vremya I My" and reviewed over 100 artists in his magazine under the pen name Viktor Petrovsky,[7] including Mikhail Chemiakin, Ernst Neizvestny, Mikhail Turovsky, Komar and Melamid, Mikhail Belomlinsky, and Oscar Rabin. Sixty-six covers of "Vrema I My" magazine were illustrated by a Russian-American artist Vagrich Bakhchanyan.[31]

After his immigration to the United States with an EB-1A Green Card, Perelman's essays were often published in various Russian language publications in the West such as Russkaya Mysl,[32] Novoe Ruskoe Slovo, Panorama,[33] Evreyskaya Gazetta, Megapolis Express, Boston Time, and others. In Russia, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, he also appeared in Russian publications such as Ogoniok,[34] Rodina,[26] and Yunost.[35]

Perelman was known to discover the writer Boris Khazanov (Russian: Борис Хазанов)[36][37][38] and his Time and We Publishing House was the first to translate to the Russian language “KGB Today: The Hidden Hand” by American journalist John Barron (Russian: КГБ Сегодня).[39]

Viktor Perelman died on November 13, 2003, after a long illness, at his home in Cliffside Park, New Jersey. He was 74 years old. He is buried in Paramus, New Jersey. He is survived by his wife, Alla Perelman, his only daughter, Irina Perelman-Grabois, and three American-born grandchildren Mark Grabois, Lara Grabois and Victoria Grabois.

Books

[edit]Perelman was the author of an autobiographical novel in Russian, "Forsaken Russia" (Russian: Покинутая Россия),[8] depicting the struggles of a journalist within a Soviet society governed by heavily censored state press. Its first edition was published in 1977 and its second edition was published in 1989. In 1977, the first two-book edition of "Forsaken Russia" won the Second Prize for Dissident Literature in Translation from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel. In 1981, he wrote and published a second autobiographical novel "The Theater of Absurd" (Russian: Театр Абсурда),[40] described by him as "comedic-philosophical narrative of my two emigrations: the experience of anti-memoirs”. In 1992, he wrote a fiction novel titled “The Sinful Fall of Caesar” (Russian: Грехопадение Цезаря).[10] His three books are available at university libraries around the globe.[41][42]

Viktor Perelman also ran the "Time and We Publishing House," wherein he published the following books:

- John Barron. "KGB Today." First ever translation to Russian. (1984). (Russian: Джон Бэррон. "КГБ сегодня.")

- Aleksander Orlov. "The Secret History of Stalin Crimes." (1991). (Russian: Александр Орлов. "Тайная история Сталинскиx преступлений.")

- Vladimir Soloviyov & Elena Klepikova. "The Battle in Kremlin: from Andropov to Gorbachev." (1986). (Russian: Владимир Соловьев и Елена Клепикова. "Бopьба в Кремле: от Андропова до Горбачева.")

- Boris Khazanov. "Me, Resurrection, and Life." (1985). (Russian: Борис Хазанов. "Я Воскресение и Жизнь.")

- Gordon Brooke-Shefferd. "The Faith of Soviet Defectors." (1983). (Russian: Гордон Брук-Шефферд. "Судьба советских перебежчиков.")

- Time and We Publishing House (New York). "Almanac of 'Time and We' 1990: Hands Off Venus de Milo." Featuring A. Galich, S. Dovlatov, A. Kestler, and an interview with Joseph Brodsky. (1990). (Russian: Издательствo Время и мы (Нью-Йорк). "Альманах 'Время и мы' 1990: Руки прочь от Венеры Милосской.")

- Albin Michel Publishing House (Paris), and Time and We Publishing House (New York). "Le Temps et Nous." 'Time and We' almanac 1990 translated into French. (1990).

External links

[edit]- Viktor Perelman's Official Memorial Website

- Время и мы (журнал, комплект номеров) во «Второй литературе»

References

[edit]- ^ Rhode Island Herald. 'Soviet Journalist in Unofficial Article Calls On Jews To Refuse Tax Payment.' Sep. 22, 1972. [1]

- ^ Svoboda (Radio Liberty). From the broadcast 'Myths and Reputations', Ivan Tolstoy. 'Hyde Park with its Baggage: In Memory of Viktor Perelman.' Nov. 17, 2013. [2]

- ^ a b c Books Published by Time and We Publishing House. [3]

- ^ Svoboda (Radio Liberty). From the broadcast 'A Glance from New York City', Aleksander Genis. 'Russian America: From Journals to Hollywood.' Mar. 20, 2020. [4]

- ^ a b Dzhaman, Solomia. 'Literature of the Diaspora: Perelman’s “Vremya I My"' Bwog: Columbia Student News. Feb. 28, 2020. [5]

- ^ Jewish Telegraphic Agency. '21 Jews Appeal To Red Cross.' Daily News Bulletin. Dec 22, 1972. [6]

- ^ a b c d Perelman, Viktor. (Editor-in-chief). 'Time and We' Journal, Issues 1–152. (1975–2001). From the electronic library "imWerden." [7]

- ^ a b Perelman, Viktor. "Forsaken Russia" (1977). [8]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. "Theatre of the Absurd" (1984). [9]

- ^ a b Perelman, Viktor. "The Sinful Fall of Caesar" (1992). Excerpted in 'Time and We.' [10]

- ^ Articles published by Viktor Perelman in Russian diaspora and other press can be viewed on the 'In The Press' Page from his official memorial website. [11]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'The Case of Tikhomirov.' Trud (No. 122). May 27, 1956.[12]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'The Case for Alexsander Grachev.' Moskovskij Komsomolets. Dec. 26, 1957. [13]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'Chelovek Vernulsya...' Literaturnaya Gazeta. July 1970. [14]

- ^ Etkind, Efim. 'As I Am Rereading "Forsaken Russia"...' Foreword to the book by Viktor Perelman, "Forsaken Russia – A Journalist in a Closed Society." (1989). Translated from Russian by Irina Perelman-Grabois. [15]

- ^ Jewish Telegraph Agency. 'Viktor Perelman, Family, In Israel.' Daily News Bulletin. Jan. 15, 1973. [16]

- ^ The New York Times. 'Soviet Journalist Privately Urges Jews Not to Pay New Exit Tax.' Aug. 28, 1972. [17]

- ^ The New York Times. 'Soviet to Let Jewish Writer Leave Without Paying Tax.' Dec. 19, 1972. [18]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'Madua Kara Ma Shekara Beveidat Oleibrit Hamoatzot.' Al Hamishmar. Oct. 8. 1973. [19]

- ^ Radio Liberty Archives. 'Zametki Yurista: Interview with Leonid Rostov." Munich. Dec. 8, 1974. [20]

- ^ Skarligina, Elena. Moscow State University. '"Time and We" Magazine in the Context of Third Wave Immigration.' [21]

- ^ Directory Of Open Access Journals. 'SOVIET ALIYAH AS A PIVOTAL THEME OF RUSSIAN-LANGUAGE PERIODICALS IN ISRAEL: THE CASE OF “VREMYA I MI” AND “22” JOURNALS.' RUDN Journal of Russian History. (2018). [22]

- ^ Ivanov, Vissarion. Special Correspondent of Trud. 'In Russian – For The Whole World: "Vremya I My" Celebrates A Quarter Of A Century.' Trud. Jan. 26, 2000. http://viktorperelman-timeandwejournal.com/newspaper29.pdf

- ^ Columbia University Libraries. CLIO Catalog Entry. 'Vrema i my.' [23]

- ^ Indiana University Libraries. IUCAT Catalog Entry. 'Vremia i my : Mezhdunarodnyĭ demokraticheskiĭ zhurnal literatury i obshchestvennykh problem. Proza, memuary, publit͡sistika. Pervye desiatʹ let izdanii͡a.' [24]

- ^ a b Perelman, Viktor. 'Faces and Details.' Rodina. February 1993. [25]

- ^ Jewish.ru 'Галич. Жизнь под током.' Oct. 19, 2015. [26]

- ^ Memorial Site for Viktor Nekrassov. 'Статьи о Викторе Некрасове: Виктор Перельман.' [27]

- ^ Svoboda Radio Archives. 'Viktor Perelman on Frederich Gorenstein.' [28]

- ^ 'The complete catalogue of essay titles and their descriptions, written and published by Viktor Perelman in "Time and We".' [29]

- ^ Viktor Perelman's Official Memorial Website. [30]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'Illusions, Once Again.' Russkaya Mysl. Nov. 14, 1974. [31]

- ^ Panorama Newspaper. [32]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'Introduction to the Reprinted Excerpt from the Book by Alexander Orlov, "The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes."' Published by Vremiya I My Publishing House. Ogoniok (No. 46). November 1989. [33]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. 'Excerpts from his autobiographical novel, "Theatre of the Absurd."' Eunost. April 1991. May 1991. [34] [35]

- ^ Kurt, Marco. "Boris Khazanov – Writer in Freedom? Roots and Expulsion: Two Millennia." [36] ROSSICA 2:33–42.

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. "РАДОСТЬ ОТКРЫТИЯ: О ПРОЗЕ БОРИСА ХАЗАНОВА."[37]

- ^ Khazanov, Boris. "Me, Resurrection, and Life." (1985). [38]

- ^ Barron, John. "KGB Today: The Hidden Hand." (1984). Translated into Russian by Viktor Perelman.[39]

- ^ Perelman, Viktor. "Theatre of the Absurd" (1984).[40]

- ^ Princeton University Libraries. Search results: 'viktor perelman'. [41]

- ^ Harvard University Libraries. HOLLIS Search results: 'viktor perelman'. [42]