Varka and Golshah

Varka and Golshah, also Varqeh and Gulshah, Varqa o Golšāh (ورقه و گلشاه, Varqa wa Golshāh), is an 11th-century Persian epic in 2,250 verses, written by the poet Ayyuqi.[1] In the introduction, the author eulogized the famous Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud of Ghazni (r.998–1030).[1]

Varka and Golshah inspired the French medieval romantic story Floris and Blancheflour.[2]

Story

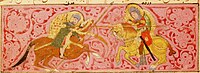

[edit]The epic is the story of the love between a youth named Varqa and a maiden, Golshah.[1] Their fathers are Arab brothers, Homām and Helāl, chiefs of the tribe of the Banū Šabīh. When Varka and Golshah were supposed to be married, Golshah was abducted by an enemy named Rabīʿ b. ʿAdnān. Various battles ensued, and Varqa's father and Rabīʿ and his two sons are killed, until Golshah was finally rescued. The wedding though is cancelled by Golshah's father, who claims that Varqa is too poor. In order to get rich, Varqa goes to the court of his maternal uncle, Monḏer king of the Yemen. Meanwhile, the king of Syria obtains Golshah's hand from her mother. When Varqa returns as a rich man, he is told that Golsha is dead, but he finds out that this is a lie. He goes to Syria to confront the king, but is treated with such kindness by him that he feels obliged to give up on Golshah. He dies of grief soon after. Golshah goes to his grave, and there dies of grief too. Their twin tombs became a place of pilgrimage for both Jews and Muslims. A year later the Prophet Moḥammad visited the tombs, and resurrected Varqa and Golsha, at last reunited.[1]

Unique 13th century edition with miniatures

[edit]

The epic is based on an old Arab story,[1] but the only known manuscript is a 13th-century edition, generally held to be a product of early 13th-century Seljuks. It is the earliest known illustrated manuscript in the Persian language, and was most probably created in Konya.[3]

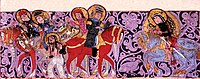

The miniatures represent typical Central Asian people, thickset with large round heads.[4] The author of the miniatures in the manuscript is the painter Abd ul-Mumin al-Khoyi, born in the city of Khoy in the Azerbaijan region.[5][6] The manuscript was completed in Konya, under the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum.[7][8] It is now located in the Topkapi Museum (Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, Hazine 841 H.841).[9] It can be dated to circa 1250.[10]

Weaponry

[edit]The paintings from the manuscript provide rare depictions of the contemporary military of the Seljuk period, and may have influenced other known depictions of Turkic Seljuk soldiers.[9][11] All depicted costumes and accoutrements are contemporary to the artist, in the 13th century CE.[5] The miniatures constitute the first known example of illustrated Persian-language manuscript, dating from the pre-Mongol era, and are useful in studying weapons of the period.[5][12] Particularly, metal face masks and chainmail helmets in Turkic fashion, and armor with small metal plates connected through straps, large round shields (the largest of them called "kite-shields") and long teardrop shields, armoured horses are depicted.[5] The weapons and armour types depicted in the miniatures were common in the Middle East and the Caucasus in the Seljuk era.[5]

-

Rabī‘ cuts the head of his adversary. Battle scene, in Varka and Golshah, mid-13th century Seljuk Anatolia.

-

Rabi wounds Varqa in the thigh. Varka and Golshah, mid-13th century Seljuk Anatolia

-

Gulshah (right) disguised as a man, confronts the kidnapper Rabi. Behind, Varqa is wounded and bound. Varka and Golshah, mid-13th century Seljuk Anatolia

-

Gulshah kills Rabi ibn Adnan with her lance. Behind her is her defeated lover Varqa, wounded and bound

-

Exit of the armed Warqah from the walls of Yemen, flanked by two riders (37, 35b)

-

The army of Warqah scatters that of Bahrain and of ‘Adan

-

Warqa overthrows a warrior of Aden

-

Resurrection of Warqah and Gulshāh by the Prophet. Behind him his four friends and future caliphs, and the king of Shām (Syria).[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Dj. Khaleghi-Motlagh. "ʿAYYŪQĪ". In Encyclopædia Iranica. December 15, 1987. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ Khaleghi-Motlagh, Dj. "ʿAYYŪQĪ". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Hillenbrand 2021, p. 208 "The earliest illustrated Persian manuscript, signed by an artist from Khuy in north-west Iran, was produced between 1225 and 1250, almost certainly in Konya. (Cf. A. S. Melikian-Chirvani, ‘Le roman de Varqe et Golsâh’, Arts Asiatiques XXII (Paris, 1970))"

- ^ Waley, P.; Titley, Norah M. (1975). "An Illustrated Persian Text of Kalīla and Dimna Dated 707/1307-8". The British Library Journal. 1 (1): 42–61. ISSN 0305-5167. JSTOR 42553970.

A unique Seljùq manuscript in the Topkapi Sarayi Museum Library (Hazine 841) (fig. 7). This manuscript, the romance Varqa va Gulshah, probably dates from the early thirteenth century . The figures in the miniatures with the typical features of Central Asian people are squat and thickset with large round heads. They are to be seen again in a more sophisticated form in the so-called Turkman style miniatures produced in Shiraz c. 1460-1502 under the patronage of another dynasty of Turkman invaders.

- ^ a b c d e Sabuhi, Ahmadov Ahmad oglu (July–August 2015). "The miniatures of the manuscript "Varka and Gulshah" as a source for the study of weapons of XII–XIII centuries in Azerbaijan". Austrian Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (7–8): 14–16.

- ^ Full name of the artist: 'Abd al-Mu'min b. Muhammad al-Naqqash al-Khuyi. The signature of the artist appears in fol.58v of the manuscript. His name also appears in relation to the foundation of the Karatay Madrasa by the Seljuk amir Jalãl al-Din Karatay in 1253-54 CE at Konya. His name (nisbah) al-Kliuyi indicates that he was from Khuy, Azerbaijan. (Grube 1966 p .73; Melikian-Chirvani 1970 pp.79-80; Rogers 1986 p.50).

- ^ Blair, Sheila S. (19 January 2020). Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh University Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-4744-6447-5.

- ^ Necipoğlu, Gülru; Leal, Karen A. (1 October 2009). Muqarnas. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (14 May 2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. OUP USA. p. 214-215. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. p. 91, 92, 162 commentary. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

The two scenes in the top and bottom registers (...) may be strongly influenced by contemporary Seljuk Persian (...) like those in the recently discovered Varqeh and Gulshah (p.92) (...) In the painting the facial cast of these Turks is obviously reflected, and so are the special fashions and accoutrements they favored. (p.162, commentary on image from p.91)

- ^ Gorelik, Michael (1979). Oriental Armour of the Near and Middle East from the Eighth to the Fifteenth Centuries as Shown in Works of Art (in Islamic Arms and Armour). London: Robert Elgood. p. Fig.38. ISBN 978-0859674706.

- ^ Necipoğlu, Gülru; Leal, Karen A. (1 October 2009). Muqarnas. BRILL. p. 235. ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1.

Sources

[edit]- Hillenbrand, Carole (2021). The Medieval Turks: Collected Essays. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1474485944.

![Resurrection of Warqah and Gulshāh by the Prophet. Behind him his four friends and future caliphs, and the king of Shām (Syria).[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Resurrection_of_Warqah_and_Gulsh%C4%81h_by_the_Prophet._Behind_him_his_four_friends_and_future_caliphs%2C_and_the_king_of_Sh%C4%81m_%28Syria%29.jpg/200px-Resurrection_of_Warqah_and_Gulsh%C4%81h_by_the_Prophet._Behind_him_his_four_friends_and_future_caliphs%2C_and_the_king_of_Sh%C4%81m_%28Syria%29.jpg)