User talk:Zslavo/Test article

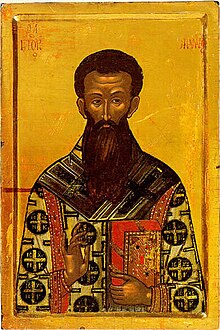

Palamism or the Palamite theology comprises the teachings of Gregory Palamas (c. 1296–1359), whose writings defended the Eastern Orthodox notion of Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam. Followers of Palamas are sometimes referred to as Palamites.

Seeking to defend the assertion that humans can become like God through deification without compromising God's transcendence, Palamas distinguished between God's inaccessible essence and the energies through which he becomes known and enables others to share his divine life.[1] The central idea of the Palamite theology is a distinction between the divine essence and the divine energies[2] that is not a merely conceptual distinction.[3]

Essential

[edit]This teaching is given in the discussion of Saint Gregory Palamas with similar Latin theology like Barlaam of Seminara and Thomas Aquinas, about the nature of grace and deification. Palamus formulated his theological synthesis against the Latin scholastic theologians, relying mainly on the experience of the holy hesychasts, reading especially Macarius, Maximus the Confessor and John of Damascus.

a) Contrary to those who taught that the Tabernacle light was only a "symbol" of Christ's divinity, St. Gregory of Palamas shows that this light is energy radiating from the divine essence, like the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, that it is hypostasized and uncreated and has no hypostasis. The "eruption" of God from Himself, the shining outward of His personal invisible image.

b) Against Barlaam, who reduced deification to a simple imitation of God, Palamas developed the teaching that deification is real participation, personal communion with God, without the interference of nature. Worshiping grace is a phenomenon that transmits power from the deified human nature of Christ into our lives; hence salvation is the mysterious change of man into god.

c) In addition to all of God's presence in His uncreated energies, the mystery of His essence remains unknown. Knowledge means direct union with God, penetration into the interior of God as much as is allowed to man, although he will never be able to understand and exhaust the divine essence.

Palamas' theory does not imply the separation of essence and energy in divinity, nor does it imply the absorption of man into the essence of God, as the Roman Catholic interpretation underlies ilamism, which avoids making a direct connection between the doctrine of grace and the doctrine of deification.

Hesychasm

[edit]Silence, stillness, inner concentration; the ascetic tradition of monastic origin (IV-V century), which was organized as a real movement of spiritual and theological revival, by introducing "Jesus' prayer" as a way of creating a state of inner concentration and peace where the soul listens and opens to God. "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on the sinner." The real founder of hesychasm is John the Ladder (649), the writer of the "Paradise Ladder", in which he recommends a monologue prayer.[4]

Energy

[edit]The teaching of energies and deeds, or divine uncreated actions, is the fruit of the later development of Byzantine theology; this teaching gained essential importance in the discussion of St. Gregory of Palamas with the scholastic Latin theologians, Barlaam and Aquinas, on the nature of grace and deification. The term energy has been used in Christological discussions before, and the Sixth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople, 681), which condemned monothelitism, gave it great importance.

For St. John of Damascus, the term energy has the meaning of realization or embodiment of every nature. Applying it to Christology, he starts from the position that every nature has its own will, action and deed, therefore two natures and two natural deeds should be recognized in Christ according to two natures, divine and human.

These two deeds are united and work together with each other because of their unique Hypostasis, in which the deeds of human nature are united with the deeds of divine nature, so they appear as God-man deeds. The difference between nature, will and deeds is recognized in the unity of the Hypostasis, because even when he took the human body, the Son is "One of the Trinity", the same Lord who works through them, unmerged, unchangeable, indivisible and inseparable.

Saint Maximus also claims that the deity is a source of energy (an idea taken from Palaman theology). In a general sense, energy is the power of God that creates movement in matter. For Saint Maximus, divine energies are nothing but divine logos in their concrete action, observable on the empirical level of things. In these divisions of logos can be known as energies: creative, contemplative, and judicial. With the help of energies, God moves the creation and moves in them, while still remaining immovable and unchangeable.

In discussions with Latin theologians about the nature of the Tabor Light (who, under the pretext of the inconsistency and indivisibility of the divine nature, said that grace was created), St. Gregory Palamas (1359) distinguishes between a) being or the essence of God, and inexpressible, and b) divine uncreated energies, ie actions or personal "exposures" through which He manifests, allowing us to partake of or worship Him. The energies spring from the common deity of the Three Hypostases of the Holy Trinity, and are therefore unique, indivisible, permanent and permanent.

The doctrine of divine uncreated energies is an essential characteristic of Orthodoxy. This teaching is based on faith in the character of the hypostatic God, in the deification of man and the transformation of matter. Unlike Roman Catholic Latin theology, which tends towards substantialism, Orthodox theology understands grace as energy and divine sharing, personal and uncreated, through which man becomes a "communicant of divine nature". Certainly, the difference between essence, hypostasis and energy should not be exaggerated, since the Church rejected emanationism and modalism. Also, deification should not be understood as the physical absorption of matter into the essence of God. Palamism is nothing but a testimony to the radical conflict between two "theologies": scholastic substantialism and patristic personalism, conceptions that have been reflected in many areas of dogmatics, especially sotiriology and sacramental theology.[5]

Orthodox teaching

[edit]Orthodox theology understands grace as energy and divine sharing, personal and uncreated, through which man becomes a "partaker of the divine nature". Also, deification should not be understood as the physical absorption of matter into the essence of God. Palaism is nothing but a testimony to the radical conflict of two theologies: scholastic substantialism and patristic personalism, concepts reflected in many areas of dogmatics, especially soteriology and sacramental theology.[6]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gerald O'Collins, Edward G. Farrugia. A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Paulist Press 2000) p. 186/260.

- ^ Fred Sanders, The Image of the Immanent Trinity (Peter Lang 2005), p. 33.

- ^ Nichols, Aidan (1995). Light from the East: Authors and Themes in Orthodox Theology. Part 4. Sheed and Ward. p. 50. ISBN 9780722050811.

- ^ Исихазам

- ^ Духовни и културни препород у XIV веку

- ^ Изложење наопаког

Bibliography

[edit]- Vladimir Lossky The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, SVS Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-31-1) James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991. (ISBN 0-227-67919-9)Copy online

- David Bradshaw. Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom. Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-521-82865-1, ISBN 978-0-521-82865-9. p. 245.

- Anstall, Kharalambos (2007). "Ch. 19, "Juridical Justification Theology and a Statement of the Orthodox Teaching"". Stricken by God? Nonviolent Identification and the Victory of Christ. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6287-7.

- Georges Barrois 1975, ‘Palamism Revisited’, Saint Vladimir's Theological Quarterly (SVTQ) 19, 211–31.

- Gross, Jules (2003). The Divinization of the Christian According to the Greek Fathers. A & C Press. ISBN 978-0-7363-1600-2.