User:Yerevantsi/sandbox/azatagrakan

The Armenian national liberation movement[3][4][5] (Armenian: Հայ ազգային-ազատագրական շարժում)[note 3] aimed at the establishment of an Armenian state. It included social, cultural, but primarily political and military movements that reached their height during World War I and the following years.

Influenced by the Age of Enlightenment and the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire, the Armenian national movement developed in the early 1860s. The factors contributing to its emergence made the movement similar to that of the Balkan nations, especially the Greeks.[23][24] The Armenian élite and various militant groups sought to improve and defend the mostly rural Armenian population of the eastern Ottoman Empire from the Muslims, but the ultimate goal was the creation of an Armenian state in the Armenian-populated areas controlled at the time by the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire.[11][3]

Since the late 1880s, the movement turned into an armed conflict (guerrilla warfare)[25] with the Ottoman government and the Kurdish irregulars in the eastern regions of the empire, led by the three Armenian political parties named Hnchak, Armenakan and Dashnaktsutyun (or Dashnak). Armenians generally saw Russia as their natural ally in the fight against Turks, however, Russians as well maintained an oppressive policy in the Caucasus. Only after losing its presence in Europe after the Balkan Wars, the Ottoman government was forced to sign the Armenian reform package in early 1914, pushed by European power and Russia, however, World War I disrupted it.

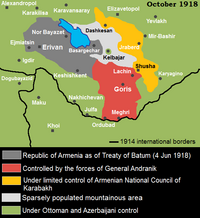

During World War I, the Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire were systematically exterminated by the government in the Armenian Genocide. According to some estimates, from 1894 to 1923, about 1,500,000—2,000,000 Armenians were killed by the Ottoman Empire.[26] Tens of thousands of Armenians joined the Russian army as volunteers in a Russian promise for an antonomy. By 1917, Russia controlled many Armenian-populated areas of the Ottoman Empire. After the October Revolution, however, the Russian troops retreated and left the Armenians irregulars one on one with the Turks. The Armenian National Council proclaimed the Republic of Armenia on May 28, 1918, thus establishing an Armenian state in the Armenian-populated parts of the Southern Caucasus.

By 1920, Mustafa Kemal's Ankara Government and the Bolsheviks in Russia have successfully came to power in their respective countries. The Turkish revolutionaries successfully occupied western half of Armenia, while the Red Army invaded and annexed the Republic of Armenia in December 1920. A friendship treaty was signed between Bolshevik Russia and Kemalist Turkey in 1921. The formerly Russian-controlled parts of Armenia were mostly annexed by the Soviet Union, in parts of which the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic was established. Hundreds of thousands of genocide refugees found themselves in the Middle East, Greece, France and the US giving start to a new era of the Armenian diaspora. Soviet Armenia existed until 1991, when the Soviet Union disintegrated and the current (Third) Republic of Armenia was established.

Background

[edit]

The Kingdom of Armenia was disintegrated in 1045 and was subsequently ruled by the Byzantine, Mongol, Safavid, various Turkic, Ottoman and Russian empires. Although an Armenian kingdom existed from 12th to 14th centuries in Cilicia, the main Armenian-populated regions in the Armenian Highland were under foreign domination since the 11th century.

The enlightenment among Armenians, sometimes called as renaissance of the Armenian people, came from two sources. The first source was the Armenian monks belonging to the Mekhitarist Order. The second source was the socio-political developments of the 19th century, mainly the French Revolution and establishment of "Russian revolutionary thought." In Turkish Armenia, Mekhitarists emphasized importance of the teaching of Armenian history and language. The Nersisyan School in Tiflis (1824) and Lazaryan School in the Institute in Moscow (1816) were the foremost educational institutions in developing national awareness. Among the pioneers Mikayel Nalbantian, Khachadour Abovian and Stepan Nazarian are to be counted. They championed the Armenian cause, and fought for its recognition. In the Ottoman Empire the conditions of Armenians improved owing to the "Tanzimat reforms" and better transport.[30]

The Armenian National Constitution defined the condition of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, but also it had regulations defining the authority of the Patriarch. The constitution of the Armenian National Assembly was seen as a milestone by progressive Armenians. Besides these improvements a second development was the introduction by Protestant missionaries of elementary education, colleges and other institutions of learning. Communications improved with the starting of Armenian newspapers. Books about Armenian history enabled a comparison of the past with current conditions and expanded readers' horizons.[30] This was part of an evolution in Armenian political consciousness from purely cultural romanticism to a programme for action.[30]

During the 19th century, along with the other national movements, a nascent Armenian intelligentsia promoted the use of new concepts in society with a particularly Armenian import. These concepts were developed by an intelligentsia which had studied in Western Europe under the influence of the legacy of the French Revolution of 1789. They were highly educated (doctors, academics, etc.) who espoused a democratic-liberal ideology and the concept of the rights of man. The second wave come with the emergence of Russian revolutionary thought. At the end of 19th century a movement was based on a socialist ideology, specifically in its Marxist variant, see Armenian Revolutionary Federation.[31] There was a major problem, in that materialism and class struggle did not directly apply to the realities (Socioeconomics) of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire as much as to those in the Russian Armenia.

Ottoman Empire

[edit]Three important developments influenced the direction of Armenian life in Ottoman lands. First, the 1839 Tanzimat decrees that attempted to modernize the Ottoman Empire and consolidate its integrity against internal and external pressures. Second, the internationalization of the ‘Armenian Question’ in the Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin, both in 1878. Third, the 1890 formation of the Hamidiye corps, irregular Kurdish cavalry formations that operated in the eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire and were intended to securitize the area, including quelling Armenian revolutionary activity. Within half a century, these three development strained relations between the groups. [32]

Second, the genesis of Armenian political activity in the eastern region and internationally can be partly linked to this counterproductive policy. Armenians began organizing their defence against increased tribal harassment, abuse of power, violence, administrative corruption and expropriation. Moreover, the Armenian Patriarchate and educated Armenian elites began pushing the Ottoman government for change by demanding reforms and changes. Th e simmering conflict escalated in the 1860s and 1870s, culminating in the San Stefano treaty of 1878, when Armenian political elites succeeded in drawing European attention to their cause. From then on, the question of the Ottoman eastern provinces (vilayât-ı şarkîye) became a permanent item on the international political agenda. Local Muslim notables and urban elites feared that the government’s measures for more equality and Armenian rights would undermine their own power base. Th is generated a polarization between Armenian urban elites and Muslim urban notables.30 [33]

A third development was depacifi cation, the crossing of the threshold from peaceful politics to violent confrontation. Conventional accounts of the Kurdish–Armenian conflict in this period blame ‘Kurds’ for their alleged innate violent nature without critically analyzing and discussing the origins or the dynamic of the confl ict.31 From the 1880s on, Armenian revolutionary parties attempted to further the Armenian cause by spreading publications, organizing demonstrations and committing political violence. Although support for the positivist revolutionary ideas among the conservative, illiterate Armenian peasant population was very limited, the Ottoman state took radical measures anyway. Sultan Abdülhamid II (1842–1918) felt the need to counterbalance the growing activity and influence of parties and drew up irregular militias from Kurdish tribes in 1890. Chieft ains were asked to provide young men for a school established in Istanbul. Th e 36 mounted and well-armed militia from Kurdish tribes from diff erent areas each recruited 1,200 members and were named aft er the sultan: the Hamidiye regiments. It had the character of an unruly group of fi ghters rather than a disciplined army with a[33] strict hierarchy. Their performance in combat was poor and a great deal of opportunism, greed and grievance motivated the irregulars. Th rough the sudden empowerment and impunity vouched for by the Sultan, the Hamidiye regiments not only assaulted Armenian villages, but also Turkish and Kurdish ones. The depacification caused by the Hamidiye was a breeding ground for a wave of robberies, rapes and murders that went unpunished.32 In their turn, some of the most activist Armenian revolutionaries pledged revenge and operated as partisans, assaulting Hamidiye chieftains. At its pinnacle, this conflict resembled an asymmetrical, low-intensity civil war.33 [34]

The conflict boiled over in the 1895 countrywide massacres of Armenians, a point of no return. In a macabre way, it temporarily ‘settled’ the Armenian question by delivering a blow so strong it crushed the community into acquiescence. Th eusurpations and encroachments on Armenian property had not disappeared, but only increased. Having their lands seized, the Armenian peasantry was now deprived of their source of livelihood and many fl ed abroad. Subsequent Ottoman governments forestalled restitution, despite attempts at restitution or compensation by the Patriarchate and Armenian political parties. In 1912 the Armenian Patriarchate appealed to the government by listing a depressing list of injustices: it decried the lack of eff ective reforms, discussed the lack of justice for Armenian refugees and migrants, underscored the widespread problem of robbery, questioned the legal diffi culties Armenians experienced in reclaiming their ‘usurped properties’ (emvâl-i mağsube). It concluded that the long-term aggregate of these crimes amounted to ‘economic carnage’ (iktisadi katliam).34 Th e report recognized that the Patriarchate was acting as interlocutor for all Armenians, but it certainly had its own bone to pick as well. It incurred losses during the 1895 massacres, the 1909 Adana massacre and potentially more. For example, in 1914 the Armenian church owned a considerable amount of property in Anatolia, including 120,000 hectares of forest land.35 A few months later, Leon Trotski, then a correspondent for Kievskaya Mysl, wrote from Salonica that the government had ‘appointed a commission which was to proceed to the localities concern and effect a settlement of the land question on the spot’.36 But the outbreak of the Balkan wars precluded the commission from functioning – or served as a pretext for its abortion. From then on, Ottoman Armenian life only went downhill. [34]

Early stages: 1862–1885

[edit]

Zeytun uprising

[edit]The first armed uprising against the Ottoman government by Armenians took place in Zeytun in 1862.[35] Zeytun (now Süleymanlı) was a large mainly-Armenian populated town in Taurus Mountains in upper Cilicia.[35] During the Late Middle Ages and the Early modern period, Zeytun was semi-independent from the Ottoman Empire and was ruled by local ishkhans.[36] After the Crimean War in the mid-1850s, the Ottoman government tried to settle Tatars in the region by confiscating Armenian property, which provoked a resistance from the local Armenians.[37] By the summer of 1862, a dispute arose between Armenians and Turks in the Zeytun district. On August 2, 1862, Aziz Pasha of Marash sieged Zeytun with his 40,000-strong army, where he faced around 5,000 Armenians volunteers. The Turkish forces eventually were forced to retreat.[38] After being defeated, the Turks decided to attack Zeytun once again. However, the pressure from Napoleon III and the influential Constantinople Armenian elite resulted in the Sublime Porte to change their plans.[1]

As a direct result of the Zeytun uprising, the Armenian intelligentsia of Constantinople was inspired by ideas of creating an Armenian state in Cilicia.[39] At around the same time, Armenian uprisings occurred in Van and Erzerum provinces. In early 1862, local Armenians and Kurds stood up against Turkish rulers in Van.[40] In Mush, Armenians revolted against the Kurdish brutalities.[41] In 1867, in response to Armenian complaints in the Bulanık region, the Grand Vezier said "If Armenians do not like things as they are in these provinces, they may leave this country; then we can repopulate these places with Circassians."[41]

"The 1860s witnessed a rise in the Armenian liberation movement, insurrections in Van and Zeytun in 1862 and Mush in 1863.

http://books.google.com/books?id=h3PZM3mZXOAC&pg=PA20&dq=%22Armenian+liberation+movement%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ZMGaUay7EtHL0gGP-4C4CQ&ved=0CEwQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=%22Armenian%20liberation%20movement%22&f=false

[42]

National enlightenment

[edit]In 1863, the Armenian National Constitution was approved by the Ottoman government. The Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople began to share his powers with the Armenian National Assembly and limited by the Armenian National Constitution. He perceived the changes as erosion of his community.[43]

The Union of Salvation (Միութիւն եւ փրկութիւն) was founded in Van in 1872. It was the first "organized revolutionary society" in the Armenian-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire.[44]

Major Armenian writers of the era, Mikael Nalbandian and Raphael Patkanian, influenced the early stages of the revolutionary movement. Besides secular activists, Armenian religious leader also played a key role in the movement, such as the Patriarch of Constantinople Mkrtich Khrimian, who later became the Catholicos of All Armenians.[45] Khrimian established the first Armenian periodical in Western Armenia, Artsiv Vaspurakan, which was published at Varagavank. Raffi and Garegin Srvandztian were among its most prominent editors.[44]

He established a printing press at Varagavank in Van, and thereafter launched in 1885 Artsiv Vaspourakan (meaning Eagle of Vaspourakan), which is considered the first Armenian periodical publication in Armenia. Garegin Shrvandztyants and Arsen Tokhmakhyan also worked on this periodical together with other pupils of a school founded by Khrimyan.

Russo-Turkish War and the internalization of the Armenian question

[edit]

Political parties and the armed movement: 1885–1905

[edit]

A third development was depacification, the crossing of the threshold from peaceful politics to violent confrontation. Conventional accounts of the Kurdish– Armenian conflict in this period blame ‘Kurds’ for their alleged innate violent nature without critically analyzing and discussing the origins or the dynamic of the conflict.31 From the 1880s on, Armenian revolutionary parties attempted to further the Armenian cause by spreading publications, organizing demonstrations and committing political violence. Although support for the positivist revolutionary ideas among the conservative, illiterate Armenian peasant population was very limited, the Ottoman state took radical measures anyway. Sultan Abdülhamid II (1842–1918) felt the need to counterbalance the growing activity and influence of parties and drew up irregular militias from Kurdish tribes in 1890. Chieftains were asked to provide young men for a school established in Istanbul. Th e 36 mounted and well-armed militia from Kurdish tribes from different areas each recruited 1,200 members and were named aft er the sultan: the Hamidiye regiments. It had the character of an unruly group of fighters rather than a disciplined army with a [33] strict hierarchy. Th eir performance in combat was poor and a great deal of opportunism, greed and grievance motivated the irregulars. Th rough the sudden empowerment and impunity vouched for by the Sultan, the Hamidiye regiments not only assaulted Armenian villages, but also Turkish and Kurdish ones. Th edepacification caused by the Hamidiye was a breeding ground for a wave of robberies, rapes and murders that went unpunished.32 In their turn, some of the most activist Armenian revolutionaries pledged revenge and operated as partisans, assaulting Hamidiye chieftains. At its pinnacle, this conflict resembled an asymmetrical, low-intensity civil war.33[34]

The movement was led by the main three traditional political parties: Armenakan, Hnchak, Dashnak. The first of these parties was Armenakan, established in Van by Mekertich Portukalian in 1885. It marked the beginning of an armed movement against the Ottoman government and the Kurdish irregular forces in the Van region.[35] Their view on how to liberate Armenia from the Ottoman Empire was that it should be through the press, national awakening and unarmed resistance.[citation needed] Two years later in 1887, the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (Hnchak) was established in Geneva, Switzerland by group of students. It became the first socialist party in the Ottoman Empire. In 1890, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) was founded in Tiflis. Its members armed themselves into fedayee groups to defend Armenian villages from widespread oppression, attacks and persecution of the Armenians. Its initial aim was to guarantee reforms in the Armenian provinces and to gain eventual autonomy, it being seen as the only solution to save the people from Ottoman oppression and massacres.

Significant European and American movements began with the Armenian diaspora in France and in the U.S. as early as in the 1890s. The previous migrations were minor or and had not been statistically significant. Various political parties and benevolent unions, such as branches for the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutiun), the Social-Democrat Henchagian party (Hnchak), and the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) which was initially founded in Constantinople, were established wherever there was a considerable number of Armenians.

With the emergence of the three main political parties, the Armenian national awakening transformed into an armed struggle by the late 1880s. The Armenakans mainly operated in and around the city of Van. In May 1889 they launched an expedition into Western Armenia from the Irani city Salmas.

- general

The involvement of the European powers in the Armenian Question provided a powerful impetus to the previously suppressed aspiration for national liberation and led to the development of a national liberation ideology and a fundamental transformation in Armenian national identity.[48]

Bashkale Resistance was the bloody encounter of three revolutionaries of Armenakan on May 1889.[49] Bashkale was a town in the Van Province. The comrades Karapet Koulaksizian, Hovhannes Agripasian, and Vardan Goloshian were stopped and demanded that they disarm. On them were two documents addressed to Koulaksizian, one from Avetis Patiguian of London and the other from Mëkërtich Portukalian, in Marseille. Ottoman's believed that the men were members of a large revolutionary apparatus and the discussion was reflected on newspapers, (Eastern Express, Oriental Advertiser, Saadet, and Tarik) and the responses were on the Armenian papers. In some Armenian circles, this event was considered as a martyrdom and brought other armed conflicts.[50] The Kum Kapu demonstration occurred in the Kumkapı district of Constantinople on July 27, 1890. The cause of the demonstrations were "..to awaken the maltreated Armenians and to make the Sublime Porte fully aware of the miseries of the Armenians."[51] The Hnchaks had came to a conclusion that the demonstrations at Kum Kapu were unsuccessful.[52] Similar demonstration on a lesser scale followed throughout most of the 1890s.[53]

Hamidian massacres: 1894-1896

[edit]Sultan Abdülhamid’s response to these movements was to massacre nearly 200,000 Armenians in the years 1894–6. These crimes, of which we still have no comprehensive study, had an organized character; it is beyond doubt that the Sublime Porte was directly implicated in them. Although they cannot be called genocidal, they seem to have been intended to reduce the Armenian population at large and weaken it at the socioeconomic level. They also unleashed a debate within the Committees and the Armenian population about the revolutionary acts of self-defense supposed to have brought on this bloody repression. This debate lastingly poisoned relations within the Ottoman Armenian community: it of course raises questions about the psychological effects of mass murder, but also about the practices of the Hamidian regime, the role of violence in Turkish society, and that society’s way of dealing with political questions.[54]

The massacres contributed heavily to turning Western public opinion against the Ottoman Empire.[55]

The seizure of the Banque Ottomane by militants of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) on 26 August 1896 is another event that serves as a yardstick with which to measure the Young Turk and Armenian positions. The operation, the kind that the press delighted in covering, found a much broader international echo than the massacres of autumn and winter 1895–6, doubtless because it struck directly at European ! nancial interests. 20 This was, however, not a peaceful demonstration like the one that had taken place in October 1895; most of the French press reacted very harshly, painting the Armenians as terrorists. [56]

"Armenian defense was generally ineffective, with the area around the traditionally rough mountain town of Zeytun as the main exception, where under the command of some Hnchaks local Armenians rose in revolt and killed the Ottoman garison to the last man. In this area, something resembling a civil war between Armenians and Muslims raged for months before being brought to an end through mediation by the Great Powers. Zeytun was exclusively inhabited by Armenians, who were strongly independently minded and had a reputation for boldness, even maintaining that they had been granted independence by the sultans. [58]

Before the July 1908 revolution, one of the activities of the Armenian fedayis had consisted precisely in struggling against nomadic tribes who attacked villagers.[59]

Indeed, the question of self-defense and the disparity between the situations of the armed Kurds and the defenseless sedentary population recurred again and again.[60]

Young Turk Revolution and the Second Constitutional Era: 1908-1914

[edit]That the ARF and CUP united around common goals [61]

The latent revolt simmering in the armed forces, the ! rst signs of civil disobedience, and the fact that it proved impossible to carry out the Sublime Porte’s orders to bring the situation back under control left the sultan no other choice than to sign the decree restoring the constitution. It was promulgated on 24 July 1908. [62]

Hnchaks opposed it [63]

The fedayi leaders found the first months after the restoration of the Constitution difficult: after years of combat and a rough-and-ready life in the mountains of the area, they felt that they had suddenly become useless. Ruben was among the first to draw the consequences and left for Europe to study engineering. The fedayis had lost their motivation. Their romanticism had turned into bitterness. They had seen themselves as the incarnation of the nation, as its “saviors”; now they were forced to accept the strategy of collaboration dictated by the intellectuals of the capital. [64]

The strategy of cooperating with the Young Turks adopted at the 1907 Fourth General Congress was confirmed at this meeting, which also ratified the more recent decisions to disarm the fedayis and engage in legal activities as well as to work toward improving the educational level of the population.[65]

The Kurdish begs, conservatives who had, generally speaking, been shown all the honors under Abdülhamid, were suspicious of these Young Turk militants, who spoke French with the Armenian revolutionaries and had dared to attack the Ottoman sovereign and caliph. [65]

Vrtanes Papazian, an official ARF candidate, later described with a wealth of detail how the joint CUP-ARF meetings were organized in Van and the surrounding region. The campaign gave rise to almost comic situations: candidates harangued meeting halls that were full to bursting, preaching “solidarity” and defending the constitution before Armenian notables who passionately hated the Dashnak revolutionaries and Muslim notables notorious for having been the previous regime’s staunchest supporters.87 The two candidates endorsed by the CUP and the ARF – Tev! k Bey, a biglandowner, and Papazian – were elected to represent the vilayet in parliament. [65]

The two Armenian deputies elected in the capital, Krikor Zohrab and Bedros Halajian,91 were not ARF members. Halajian belonged to the CUP. Interestingly, the Ottoman Constitutional Club nominated both men on 18 September in an election by secret ballot held at the Club.92 In the provinces, the ARF’s candidates were not successful everywhere, despite of! cial support from the CUP. While the Dashnaks carried the day in Erzerum, where Vartkes (Hovhannes Seringiulian)93 and Armen Garo (Karekin Pastermajian)94 were elected, and in Mush, with the victory of Kegham Der Garabedian,95 the party was defeated in other areas. Thus, Spartal (Stepan Spartalian)96 and the “Young Turk” lawyer Hagop Babikian97 were elected in Smyrna, the Hnchak Murad (Hampartsum Boyajian)98 won in Sis/Kozan, and Cilicia and Dr. Nazaret Daghavarian99 carried the day in Sıvas. [66]

Thanks to “judicious” utilization of the electoral system, the CUP won by a landslide, obtaining 160 seats, including those of Babikian and Halajian, both CUP members. Still more revealing are the ! gures that show that, of a total of 288 seats up for election, no fewer than one 140 went to Turks, 60 to Arabs, 27 to Albanians, 36 to Greeks, 14 to Armenians, 10 to Slavs and 4 to Jews. To put it differently, 220 Muslims and 46 Christians were elected to parliament. Thirty per cent of the deputies were clergymen, 30 per cent were big landowners, 20 per cent were civil servants, and 10 per cent belonged to one of the liberal professions.100 The Ittihad’s triumph was con! rmed on 17 December 1908, when parliament opened its doors to the new deputies after 30 years of silence. It was inaugurated by a “speech from the throne,” delivered by an Abdülhamid surprised by the ovation he received from the deputies. The Young Turks were not the slowest to take up his invitation to dine in Yıldız Palace on 31 December, following the example of the newly elected president of parliament, Ahmed Rıza.[66]

For the non-Turkish elements of the empire, the Imperial Ottoman model, based on millets, or ethno-religious nations, had at least the advantage of allowing them a degree of autonomy. In the Armenians’ case, the Constantinople Patriarchate was central to their collective existence. Under Abdülhamid, however, this institution, the workings of which were democratized from 1863 on, was dealt blow after blow. In September 1891, the Armenian constitution was suspended by the sultan. The Armenian chamber,107 which had its seat in Galata, was forced to break off its activities, which paralyzed the internal administration of the millet. The chamber was convened only four times in over 17 years, after the sovereign had personally authorized it to meet on 7 December 1894 to elect Patriarch Mattheos [67]

The Armenians supported the Young Turk Revolution, as it was just natural that these concepts (tendencies, attitudes and feelings) were present in varying proportions among Armenians with the turn of 20th century[68] ARF, in the early 20th century was socialists, and marxist which can be seen from the party's first program.[69] After the revolution, the Ottoman Empire in the second Constitutional Era (Ottoman Empire) was struggling to keep its territories and promoting the Ottomanism among its citizens. During the same time the Armenian Revolutionary Federation was moving out of this context and developing, what was just a normal extension of its national freedom concept, the concept of the independent Armenian state. With this national transformation Armenian Revolutionary Federation's activities become a national cause.[70]

Adana massacre

[edit]As far as the local organs of the party are concerned, the Fayk-Mosdichian report, like Babikian’s parliamentary document, shows without the least ambiguity that, in addition to the vali and the military commander of the vilayet, the presidents and members of the Union and Progress clubs of Tarsus and Adana took a direct hand in organizing massacres in those two towns. Yet, not only did the CUP deny this fact, it refused to condemn an individual as dubious as İhsan Fikri65 – although it was known that he had stirred up local public opinion by publishing articles that accused the Armenians, notably of separatism and of preparing a massacre of the Turkish population. [71]

In an 18 July 1912 declaration, the Western Bureau announced that it had effectively broken with the Young Turks.81[72]

Armenian reform package

[edit]

The projected reforms in the Armenian provinces are in many respects comparable to similar reform plans that the powers vainly tried to have implemented in Macedonia. While it is undeniable that, in the Macedonian question as well as the Armenian case, the European interference was partly motivated by political and economic interests, the fact remains that in both regions real problems of security and a disastrous economic and social situation provided a basis for the pressure that the powers put on the Sublime Porte. Abdülhamid had in some sense responded as the Ottomans often did when confronted with such domestic questions. In the West (with the possible exception of Germany), his energetic methods were depicted as “bloody.” [73]

Nubar reassured him that the Armenians were by no means pursuing autonomy, which was impracticable in the present situation, but rather sought the establishment of an administration capable of protecting their lives and property. [74]

Lepsius, speci! cally, seems to have played a major role in moving the negotiations forward, serving as an intermediary between the Patriarchate and the German embassy,47 and working hand-in-hand with Krikor Zohrab.48 Late in September 1913, it was reported that the German and Russian diplomats had reached a compromise:

- The country shall be divided into two sectors, one encompassing Trebizond, Erzerum, and Sıvas/Sepastia, and the other, all the rest. The Sublime Porte requests that the great powers appoint two inspectors, one for each sector. These inspectors shall be entitled to appoint and dismiss their subordinates. Participation in local administrative functions and representation in the assemblies and councils shall be half Christian, half Muslim.49 [75]

On 25 December, the Russians and Germans of! cially transmitted the plan for reforms in Armenia to the Ottoman government. After a few weeks of foot-dragging, the Sublime Porte ultimately approved of the agreement on 8 February 1914. It had not succeeded in obtaining suppression of the clause on Western supervision, however, which it considered decisive.54 [75]

Ivan Zavriev,66 a Dashnak leader who was very well placed in ruling circles in St. Petersburg (he was in Istanbul in 1913), played a decisive role in negotiations with the Russians, while Zohrab was the “semi-of! cial voice” of the Armenians.67 Zohrab, in his diary, remarks that Zavriev “was the ! rst Dashnak I ever knew who admitted the truth that, under a Turkish government, the sole fate awaiting the Armenian world was annihilation”; he contrasts him with Aknuni, who was “the last to part with his Turkophile dreams.”68 [76]

In spring 1913, after the London Conference, at which the Armenian project took a big step forward, the Ittihad naturally revived the practice of meeting regularly with the Dashnaks.[76]

The ! rst version of the plan, endorsed by the ambassadors in July, stipulated that only people with ! xed abodes had the right to vote and that the hamidiye regiments would be dissolved.83 The Russian-German text did not, however, provide for the restitution of con! scated land, nor did it prohibit the settlement of muhacir from the Balkans in the eastern provinces. As for the hamidiyes, they were renamed “lightly armed troops.”84 [77]

"The Turks would rather die than accept interference of any kind from the powers in the Armenian question, although they know that the country would die along with them. They regard this as ... a question of life and death for all of Turkey and their party" --- Krikor Zohrab [77]

In a telegram, St. Petersburg had instructed its diplomats to insist on three points: ! rst, that the ! fty-! fty principle be applied to the vilayet of Erzerum as well; second, that muhacir be prohibited from entering Armenia; and third, that Christians be guaranteed the right to sit on the general councils in the zones in which they were a minority – in Harput, Dyarbekir, and Sıvas.111 The Sublime Porte rejected the ! rst demand, gave an oral promise with regard to the second, and accepted the third.112 On 8 February, the agreement was of! cially signed. [77]

Russian Empire

[edit]Armenian church crisis: 1903–1904

[edit]Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov

The tsar's Russification programme reached its peak with the decree of June 12, 1903 confiscating the property of the Armenian Church. Mkrtich Khrimian (Catholicos of Armenia) revolted against the tsar. When the tsar refused to back down the Armenians turned to the Dashnaks. The Armenian clergy had previously been very wary of the Dashnaks, condemning their socialism as anti-clerical. However, ARF acquired significant support and sympathy in Russian administration. Mainly because of the ARF's attitude to the Ottoman Empire, the party enjoyed the support of the central Russian administration, as tsarist and ARF foreign policy had the same alignment until 1903.[78] The edict on Armenian church property was faced by strong ARF opposition, because it perceived a tsarist threat to Armenian national existence. In 1904, the Dashnak congress specifically extended their programme to support the rights of Armenians in the Russian Empire as well as Ottoman Turkey.

As a result, the ARF leadership decided to actively defend Armenian churches.[78] The ARF formed a Central Committee for Self-Defence in the Caucasus and organised a series of protests. At Gandzak the Russian army responded by firing into the crowd, killing ten, and further demonstrations were met with more bloodshed. The Dashnaks and Hnchaks began a campaign of assassination against tsarist officials in Transcaucasia and they succeeded in wounding Prince Golitsin. The events convinced Tsar Nicholas that he must reverse his policies. He replaced Golitsin with the Armenophile governor Count Illarion Ivanovich Vorontsov-Dashkov and returned the property of the Armenian Church. Gradually order was restored and the Armenian bourgeoisie once more began to distance itself from the revolutionary nationalists.[79]

- The Armenians: From Kings And Priests to Merchants And Commissars - Page 221

Golitsyn crudely implemented a policy of forced Russification. The most severe blow came in June 1903 when a decree was issued in violation of the 1836 Pokzhenie dictating that all properties of the Armenian church (including the schools)

As the man responsible in particular for assaults by the Russian state on the Armenian church, Golitsyn narrowly survived an attack from enraged Armenian nationalists in 1903, but departed shortly thereafter, his policies being largely

Armenian-Tatar massacres: 1905–1907

[edit]Unrest in Transcaucasia, which also included major strikes, reached a climax with the widespread uprisings throughout the Russian Empire known as the 1905 Revolution. 1905 saw a wave of mutinies, strikes and peasant uprisings across imperial Russia and events in Transcaucasia were particularly violent. In Baku, the centre of the Russian oil industry, class tensions mixed with ethnic rivalries. The city was almost wholly composed of Azeris and Armenians, but the Armenian middle-class tended to have a greater share in the ownership of the oil companies and Armenian workers generally had better salaries and working conditions than the Azeris. In December 1904, after a major strike was declared in Baku, the two communities began fighting each other on the streets and the violence spread to the countryside.

The 1905–6 “events” in the Caucasus – that is, the eruption of violence between Armenians and “Muslims,” especially the Turkish-speaking population of Baku – probably had a greater impact on Young Turk circles than has previously been supposed. While this violence resulted, on the analysis of the Armenian Committees, from a policy of provocation orchestrated by agents of the Czar’s regime,7 Turkish-speaking circles perceived it as a Turkish-Armenian con" ict for control of the South Caucasus. Bahaeddin wrote, in response to a March 1906 letter in which the Tatars of the Caucasus complained about Armenian “encroachments,” that “the authors of the detestable massacres are not you, but those Armenian revolutionaries who are enjoying themselves by offending humanity.”8 In public, the CPU’s of! cial organs took a vaguely neutral stance toward the Armenian-Tatar con" ict. In private, however, Sakir suggested “putting an end to Armenian wealth and in" uence in the Caucasus.” He also suggested to his “Muslim Brothers” that they propagate “the patriotic idea of uni! cation with Turkey” while simultaneously declaring to the Russians that they were “loyal to the Russian government” and not engaged in a religious war, but “in a stuggle against Armenians only because [they] have wearied of Armenian acts of agression, outrages, and atrocities, and only in order to defend [their property and honor.”9 [80]

Tribune of People, 1912

[edit]In January 1912, a total of 159 Armenians were charged with membership of an anti-"Revolutionary" organisation. During the revolution Armenian revolutionaries were split into "Old Dashnaks", allied with the Kadets and "Young Dashnaks" aligned with the SRs. To determine the position of Armenians all forms of Armenian national movement put into trial. The entire Armenian intelligentsia, including writers, physicians, lawyers, bankers, and even merchants" on trial.[81] When the tribune finished its work, 64 charges were dropped and the rest were either imprisoned or exiled for varying periods[81]

World War I: genocide and resistance

[edit]

December 1914, Nicholas II of Russia visited the Caucasus Campaign. Telling to the head of the Armenian Church along the president of the Alexander Khatisyan of the Armenian National Bureau in Tiflis that:

From all countries Armenians are hurrying to enter the ranks of the glorious Russian Army, with their blood to serve the victory of the Russian Army... Let the Russian flag wave freely over the Dardanelles and the Bosporus, Let your will the peoples [Armenian] remaining under the Turkish yoke receive freedom. Let the Armenian people of Turkey who have suffered for the faith of Christ received resurrection for a new free life .... [82]

- Russian-Armenian alliance, ARF

The biggest achievement is the Armenian governing of the Administration for Western Armenia with the Aram Manukian and keeping the Ottomans out with the Armenian volunteer units within the Russian Caucasus Army, as well as Armenian militia.

French-Armenian Agreement (1916) October 27, 1916, was the political and military accord regarding the support of the Armenian Resistance on the side of the allies in World War I. The aim of creating the Legion was to allow Armenians' contribution to the liberation of Cilicia region in Ottoman Empire and help them to realize their national aspirations of creating a state in that region.

Van resistance

[edit]Russian retreat

[edit]Republic of Van

[edit]

- 376

After the withdrawal of Russian troops, the Ottoman army launched a new Caucasus offensive at the beginning of 1918 and encountered fierce resistance, first from the Armenian irregulars, other members of Russian volunteer battalions and vengeful survivors of the former massacres, and then from the armies of the Armenian republic. Particularly in this region, between 1918 and 1922, massacres and counter-massacres were frequent, aimed at expanding national borders and achieving homogeneous populations. 34 Armenian atrocities committed against the Muslims eventually provided Kemal’s nationalist forces with a pretext for the invasion and obliteration of Armenia in 1920. These atrocities, committed mostly after 1917, continue to be at the centre of Turkish denialist theses, and they continue to be employed as retrospective justification of the deportations and massacres of the Ottoman Armenians. It was a ‘bloody conflict’, as Kemal repeatedly put it: both sides slaughtered each other and suffered huge losses.

- 377

The French military units, together with Armenian volunteers, assumed control of Maras, Antep and Urfa by September 1919. According to French sources, ‘some 12,000 Armenians had resettled in the southern provinces by the end of 1919’.37 Under the spectre of returning Armenians seizing their old property, the Muslim nouveaux riches threw their support behind Kemal’s nationalist forces who took control of the region in early 1920. Thousands of Christians were massacred in Maras, where inter-communal rivalries were exacerbated by the French during the occupation of the city. The atrocities committed by the Armenians were ‘dwarfed’ by the massacres in Maras by the nationalist forces;38 French aggravation of the ethnic rivalries in the region in their own imperial interests was then exploited by Kemal’s nationalists.39 Armed conflicts between the French occupiers and the nationalists in Maras, Urfa and Antep continued until the first French/Turkish armistice in May 1920.

Republic of Armenia: 1918–1920

[edit]

War with Turkey and Soviet takeover: 1920–1921

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, Dashnak) is recognized as the dominant force of the movement, however, both Hnchak and Armenakan parties played important roles, in some places surpassing the influence of the ARF.

- ^ The span of the Armenian national liberation movement is not strictly defined. Some historians claim the 1862 Zeytun uprising is its beginning.[1] The end of the movement is not specified either. Full Soviet control of Armenia was established by mid-1921, but formally, it became part of the Soviet Union and its lost its de jure independence only with the 1922 Treaty on the Creation of the USSR. Also, the Operation Nemesis, which lasted until 1922, is considered part of the movement.

- ^ also known as the Armenian liberation movement,[6][7][8][9] Armenian revolutionary movement,[10][11][12] (Armenian) Fedayee movement,[13][14][15][16] (ֆիդայական շարժում), Armenian volunteer movement[17][18][19] and Armenian revolution[20][21][22]

- Footnotes

- ^ a b Nalbandian 1967, p. 71: "The Zeitun Rebellion of 1862 became the first of a series of insurrections in Turkish Armenia against the Ottoman regime which were inspired by revolutionary ideas that had swept the Armenian world." Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTENalbandian196771" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (2011). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780199781041.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Chahinian, Talar (2008). The Paris Attempt: Rearticulation of (national) Belonging and the Inscription of Aftermath Experience in French Armenian Literature Between the Wars. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles. p. 27. ISBN 9780549722977.

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 318. ISBN 9781598843361.

- ^ Rodogn, Davide (2011). Against Massacre: Humanitarian Interventions in the Ottoman Empire, 1815-1914. Oxford: Princeton University Press. p. 323. ISBN 9780691151335.

- ^ Kaligian, Dikran Mesrob (2011). Armenian Organization and Ideology under Ottoman Rule: 1908-1914. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 149. ISBN 9781412848343.

- ^ Nichanian, Marc (2002). Writers of Disaster: Armenian Literature in the Twentieth Century, Volume 1. Princeton, NJ: Gomidas Institute. p. 172. ISBN 9781903656099.

- ^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings And Priests to Merchants And Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780231511339.

- ^ Kirakosyan, Jon (1992). The Armenian genocide: the Young Turks before the judgment of history. Madison, Conn.: Sphinx Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780943071145.

- ^ Chalabian, Antranig (1988). General Andranik and the Armenian Revolutionary Movement (. Southfield, MI.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Ishkanian, Armine (2008). Democracy Building and Civil Society in Post-Soviet Armenia. New York: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 9780203929223.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Michael A. (2011). Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9781139494120.

- ^ Chalabian, Antrang (2009). Dro (Drastamat Kanayan): Armenia's First Defense Minister of the Modern Era. Los Angeles, CA: Indo-European Publishing. p. v. ISBN 9781604440782.

- ^ Libaridian, Gerard J. (1991). Armenia at the crossroads: democracy and nationhood in the post-Soviet era : essays, interviews, and speeches by the leaders of the national democratic movement in Armenia. Watertown, Massachusetts: Blue crane books. p. 14. ISBN 9780962871511.

- ^ Høiris, Ole (1998). Contrasts and solutions in the Caucasus. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. p. 230. ISBN 9788772887081.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ter Minassian, Anahide (1984). Nationalism and socialism in the Armenian revolutionary movement (1887-1912). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Zoryan Institute. p. 19, 42. ISBN 9780916431044.

- ^ Balakian, Grigoris (2010). Armenian Golgotha: a memoir of the Armenian genocide, 1915-1918. New York: Vintage Books. p. 44. ISBN 9781400096770.

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2003). Warrant for Genocide: Key Elements of Turko-Armenian Conflict. Transaction Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 9781412841191.

- ^ Midlarsky, Manus I. (2005). The Killing Trap: Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9781139445399.

- ^ Vratsian, Simon (1950–1951). "The Armenian Revolution and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation". Armenian Review. Watertown, MA.

- ^ Giuzalian, Garnik. Hayots Heghapokhuthiunits Aratj [Before the Armenian revolution], Hushapatum H.H. Dashnaktsuthian 1890-1950 [Historical collection of the A.R. Federation 1890-1950] (Boston: H.H. Buro [Bureau of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation], 1950

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington: Indiana university press. p. 67-68. ISBN 9780253207739.

The Armenian revolution was born in a romantic haze, inspired by Russian populism, the Bulgarian revolution...

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1992). The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 129. ISBN 9780312048471.

- ^ Göl 2005, p. 128: "The Greek independence of 1832 served as an example for the Ottoman Armenians, who were also allowed to use their language in the print media earlier on."

- ^ Lewy, Guenter (2005). The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey: A Disputed Genocide. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780874808490.

- ^ Auron, Yair (2000). The Banality of Indifference: Zionism and the Armenian Genocide. Transaction Publishers. p. 44. ISBN 9781412844680.

- ^ "Division of Armenology and Social Sciences". Armenian National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "Situation in Western Armenia: The Armenian Question on the International Arena". Embassy of Armenia to the United States of America. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ ""The Armenian National Liberation Movement - 1850-1890" by M K Nersissian". Armenian News Network / Groong. University of Southern California. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ a b c Herzig, Edmund. Armenians Past And Present In The Making Of National Identity A Handbook, p. 76

- ^ Libaridian, Gerard J. (2004). Modern Armenia: People, Nation, State. Transaction Publishers. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7658-0205-7.

- ^ Üngör 2011, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c Üngör 2011, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Üngör 2011, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Nalbandian 1967, p. 67.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 68.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 69.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 70.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 74.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 78.

- ^ a b Nalbandian 1967, p. 79.

- ^ Kirakosëiìan, Arman (2004). The Armenian Massacres: 1894 - 1896 ; U.S. Media Testimony. Wayne State University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780814331538.

- ^ Migirditch, Dadian. "La society armenienne contemporaine", Revue des deux Mondes, June 1867. pp. 803-827

- ^ a b Nalbandian 1967, p. 80.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Nalbandian 1967.

- ^ Arman J. Kirakossian, British Diplomacy and the Armenian Question, from the 1830s to 1914, page 58, ISBN 978-1-884630-07-1

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 100.

- ^ Darbinian, op. cit., p. 123; Adjemian, op. cit., p. 7; Varandian, Dashnaktsuthian Patmuthiun, I, 30; Great Britain, Turkey No. 1 (1889), op. cit., Inclosure in no. 95. Extract from the "Eastern Express" of June 25, 1889, pp. 83-84; ibid., no. 102. Sir W. White to the Marquis of Salisbury-(Received July 15), p. 89; Great Britain, Turkey No. 1 (1890), op. cit., no. 4. Sir W. White to the Marquis of Salisbury-(Received August 9), p. 4; ibid., Inclosure 1 in no. 4, Colonel Chermside to Sir W. White, p. 4; ibid., Inclosure 2 in no. 4. Vice-Consul Devey to Colonel Chermside, pp. 4-7; ibid., Inclosure 3 in no. 4. M. Patiguian to M. Koulaksizian, pp. 7-9; ibid., Inclosure 4 in no.

- ^ Khan-Azat, op. cit., VI (February 1928), pp. 124-125

- ^ Nalbandian 1967, p. 119.

- ^ Hovhanissian, Richard G. (1997) The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. New York. St. Martin's Press, 218-9

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kévorkian 2011.

- ^ Joost Jongerden, Jelle Verheij (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. Leiden: Brill. p. 96. ISBN 9789004225183.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 125.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 126.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 51.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Kévorkian 2011, p. 62.

- ^ a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Der Minassian, Anahide, "Nationalisme et socialisme dans le Mouvement Revolutionnaire Armenien", in "LA QUESTION ARMENIENNE", Paris, 1983, pp. 73-111.

- ^ Documents for the history of the ARF, II, 2nd Edition, Beirut, 1985, pp. 11-14

- ^ Dasnabedian, Hratch, "The ideological creed" and "The evolution of objectives" in "A BALANCE-SHEET OF THE NINETY YEARS", Beirut, 1985, pp. 73-103

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 112.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 134.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 146.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 157.

- ^ a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 158.

- ^ a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Kévorkian 2011, p. 162.

- ^ a b Geifman, Anna (31 December 1995). Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894-1917. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-691-02549-0.

- ^ Ternon. Les Arméniens, pp. 159-62

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Abraham, Richard (1990). Alexander Kerensky: The First Love of the Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, pg. 53,54

- ^ Shaw, Stanford Jay (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. pp. 314–315.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

[edit]- Nalbandian, Louise (1967). The Armenian revolutionary movement: the development of Armenian political parties through the 19th century. Berkley-Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Çırakman, Aslı (2011). "Flags and traitors: The advance of ethno-nationalism in the Turkish self-image". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 34 (11): 1894–1912. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.556746. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 143287720.

- Kévorkian, Raymond H. (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781848855618.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2011). Confiscation and destruction: Th e Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property. New York: e Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1441-13578-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)