User:Yerevantsi/sandbox/Tekor

| Tekor Church | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Location | |

| Location | Digor, Kars, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°22′28″N 43°24′44″E / 40.374361°N 43.412333°E |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | ishkhan Sahak Kamsarakan |

| Completed | late 5th century (c. 480s)[2][3] |

| Destroyed | 1912–1960s |

Tekor Church (Armenian: Տեկորի տաճար)[a] is a destroyed Armenian church in Digor (historically Tekor), Kars Province, in eastern Turkey.

St. Sarkis

Holy Trinity

Տեկորի Ս. Երրորդություն վանքի per Hasratyan[6]

Ս. Սարգսի վկայարան[6]

Տեկորի Ս. Սարգիս վկայարանը (478–490 թթ.)[3]

The now scant remains of this important fifth century church stand on a slope overlooking the village of Digor, formerly called Tekor, located 22km southwest of Ani.[2]

Տեկորի Ս. Երրորդություն վանք, Տեկորի տաճար[6]

Անիից մոտ 20 կմ հարավ-արևմուտք, Ախուրյանի վտակ Տեկորի աջ ափին (այժմ՝ Թուրքիայում):[6]

located on the hillside in the district of Tekor[7]

Dickran Kouymjian: Not far from the Turkish Armenian border, is the church of Tekor built in the fifth century, which contained the oldest Armenian lapidary inscriptions, dated around 480.[8]

The remnants of Sourb Yerordutiun (Holy Trinity) Church, which traces back to the 5th century, are situated at the southern edge of Tekor (now: Digor) Village.[9]

In local Christian sources, the old church located on the ridge to the south of Digor Village is called "Tekor". The name of the village may have come from this. / Hıristiyan yerli kaynaklarında, Digor Köyünde güneyindeki sırtta bulunan eski kilise ‘’Tekor’’ diye anılıyor. Köyün adı da bundan gelmiş olabilir.[10]

Its destruction, along with other pieces of Armenian cultural heritage in Turkey, has been cited by the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute and Armenia's Foreign Ministry as an example of cultural genocide by Turkey.[11][12]

Foundation and later history

[edit]

According to the foundation inscription on the architrave of its western entrance,[2] it was built in the late 5th century by ishkhan (prince) Sahak Kamsarakan of the Kamsarakan family as a martyrium of St. Sargis.[6][15][16][2] The inscription also names Catholicos (patriarch) Hovhannes (John) I Mandakuni; Hovhannes, bishop of Arsharunik; Tayron, elder of the church; Manan, a hazarapet ("thousandman" or chiliarch); and a certain Uran Horom (Ուրան Հոռոմ) as founders.[6] Based on the inscription, the church has been dated to the 480s.[2][4][17] Murad Hasratyan suggested construction between 478 and 490.[3] Originally a triple-naved basilica, it construction was halted in 481–484, during Vahan Mamikonian's revolt against the Sasanian Empire, and completed in the late 400s as a domed church supported by four pillars.[6][15]

Some researchers, such as Toros Toramanian and Vahagn Grigoryan, insist that the building dates back to the pre-Christian (pagan) period and was subsequently converted to a church.[18][19]

In 724 Catholicos Hovhannes (John) III of Odzun accused Hovhannes (John), abbot of Tekor, of heresy.[6]

In the 10th-11th centuries, the Bagratunis restored and renovated the church by replaced its roof tiles with stone slabs, narrowed the windows,[6] removed the ruined portico/colonnade,[15] added ornaments depicting grapes and vines, humans, and peafowl.[16] By this time it was known as the Holy Trinity Church (Ս. Երրորդություն).[2] The period of Bagratid Armenia also saw the granting of privileges. In 971 Queen Khosrovanuysh, consort of Ashot III, released Tekor of taxes, which was reconfirmed by Queen Katranide II, consort of Gagik I in 1008, 1014, and 1018 and by by the wife of ishkhan Vest Sargis in 1042.[6]

In the 17th century, Hovhannes vardapet, abbot of Tekor, was killed while resisting attacking bandits.[6] In the 19th century, the monastery had 300 pastures that were all rented out as of 1888.[6]

It is the earliest known monument in Armenian church architecture manifesting the transformation of tri-nave basilicas into domed ones. Its walls used to bear inscriptions of rare historical value dating from 971, 989, 990, 1006, 1008, 1018, and 1036.[9]

Architecture

[edit]Սկզբնապես (12–13 շարք) Տեկորի Ս. Երրորդություն վանքի եկեղեցին կառուցվել է վարդագույն տուֆով՝ որպես եռանավ բազիլիկ; շարունակվել սպիտակավուն տուֆով՝ եկեղեցուն տալով քառամույթ գմբեթավոր հորինվածք, որի շնորհիվ այն քրիստոնեաական ճարտարապետության մեջ տվյալ տիպի հնագույն թվագրված կառույցն է:[6]

Թորամանյանի «Տեկորի տաճարը» մոնոդրաֆիկ ուսումնասիրությու մեջ ցույց է տրված, որ Տեկորի տաճարի կառուցվածքում տեղի են ունեցել ճիշտ նույն ձևափոխությունների շրջանները, որպիսիք նկատվեց Քասաղում: Ըստ այդ հետազոտության Տեկորի տաճարի սկզբնական տեսքին հավելված են՝

ա) արտաքին սյունասրահները, բ) այժմյան աբսիդի ներքուստ կորագիծ, արտաքինից բազմանիստ ծավալը, աբսիդին կից սենյակներով, գ) բոլոր ճակատների շքամուտքերը, դ) հյուսիսային ճակատի արտաքին աբսիդը, ե) գմրեթը:

Դժվար չէ նկատել, որ առանց այդ հավելվածքների Տեկորի տաճարի սկզբնական տեսքը նույնպես ստանում է բոլորովին պարզ կառուցվածք, որպիսին ունենք Քասաղում [20]

Հարուստ հարդարանք են ունեցել արտաքին ճակատները, սյունասրահների որմնասյուները, շքամուտքերը, լուսամուտների պսակները:[6]

Գերակշռել են ականթի, խաղողի որթատունկի և ողկույզների քանդակները, ոճավորված զարդաձևերը, որոնցից մի քանիսն առաջին անգամ են հանդես եկել հայկական արվեստում:[6]

Արմ. ճակտոնի հարթության մեջ, խաչաձև լուսամուտների երկու կողմերում, քանդակված են եղել երկու կիսանդրի, վերևում՝ գավաթի մեջ դրված խաղողի ողկույզ կտցահարող զույգ սիրամարգեր: Խորանը ծածկված է եղել որմնանկարներով:[6]

Տեկորի Ս. Երրորդություն վանքի եկեղեցին բարձրացել է բազմաստիճան որմնախարսխի վրա, հս-ից, արմից և հվ-ից ունեցել բաց սյունասրահներ, իսկ արտաքուստ եռանիստ ծավալով արլ-ից շեշտված խորանի երկու կողմերում՝ հս-ից հվ. ձգվող ավանդատներ: Հզոր մույթերի վրա բարձրացել է խորանարդաձև գմբեթը, որը հայկական եկեղեցական ճարտարապետության մեջ մեզ հայտնի ամենավաղ քարե գմբեթն է և իր ձևով՝ միակը:[6]

- first domed

This church is now generally held to be the earliest known domed Armenian church.[2]

քառամույթ գմբեթավոր հորինվածք, որի շնորհիվ այն քրիստոնեաական ճարտարապետության մեջ տվյալ տիպի հնագույն թվագրված կառույցն է:[6]

...Տեկորի տաճարը՝ հայկական առաջին գմբեթավոր բազիլիկ եկեղեցին...[21]

Տեկորի ... վաղագույն թվագրված քառամույթ գմբեթավոր եկեղեցին է քրիստոնեական ճարտարապետությունում:[3]

Influence

[edit]Տեկորի Ս. Երրորդություն վանքի եկեղեցու քառամույթ գմբեթավոր բազիլիկ հորինվածքը հետագայում նախատիպ է ծառայել Հայաստանի VI–XVII դդ. բազմաթիվ եկեղեցիների համար, իսկ IX–XI դդ. անցել է Բյուզանդիա ու լայն տարածում ստացել ուղղափառ (օրթոդոքս) երկրներում:[6]

Տ տ Հայաստա նի բազիլիկատիպ և կենտրոնազմբեթ շինության հնագույն նմուշն է և խոր ազդեցություն է թողել Օձունի, Մրենի, Գայանեի, Բագավանի, Անիի Մայր տաճարի և այլ շինությունների վրա: Այս ոճը 9-10-րդ դդ փոխանցվել է Բյուզանդիային և լայն կիրառություն գտել Հունաստանում, Սերբիայում և այլուր: Տ տ-ի վրա պահպանված հայերեն վիմագիր արձանագրությունը եղածների մեջ հնագույնն է:[16]

Տ․ տ․ բազիլիկատիպ և կենտրոնագըմբեթ հորինվածքների սինթեզի հիման վրա մշակված, չորս մույթեր ունեցող առաջին հորինվածքն է, որի առավել բնորոշ կողմը՝ գմբեթի հակազդումների չեզոքացումն է փոխուղղահայաց թաղերի միջոցով։ Տ․ տ–ում մշակված այս համակարգը վճռական նշանակություն է ունեցել սինթեզված տիպերի կազմավորման գործում (Օձուն, VI դ․, Մրեն, Գայանե եկեղեցի, Բագավան, VII դ․, Անիի Մայր տաճար, X դ․), այն կիրառվել է նույնիսկ XVII դ․։ Այս հորինվածքն այնքան տրամաբանական և կոնստրուկտիվ էր, որ IX–X դդ․ անցել է Բյուզանդիա և լայն տարածում գտել ուղղափառ եկեղեցու դավանանքին հետևող բազմաթիվ երկրներում՝ Հունաստանում, Սերբիայում, Ռուսաստանում։[15]

Ամբողջ կառույցը ի սկզբանե բարձրացել է բազմաստիճան որմնախարսխի վրա, որն արլ–ից շրջանցել է աբսիդի եռանիստ ելուստը։ Աբսիդի երկու կողմում՝ հս–ից և հվ–ից, տեղավորված են ձգված համաչափություններով ավանդատներ, որոնք մուտք ունեն տաճարի ներսից։ Հս․ ավանդատան ելուստը արմ–ից ունի արտաքին բաց խորան։ Տաճարը երկու մուտք է ունեցել հս–ից, մեկական՝ հվ–ից և արմ–ից։ Արմ–ից, հս–ից ու հվ–ից տաճարը շրջանցել են բաց սյունասրահները, որոնց դրսի կողմի մույթերը չեն պահպանվել, սակայն առկա են նրանց համապատասխանող որմնասյուները՝ հպված տաճարի պատերին։ Տաճարի ներսում եղել են չորս ուժեղ, առանձին կանգնած մույթեր (սկզբնապես թերևս խաչաձև, ինչպես ենթադրում է Թ․ Թորամանյանը)։ Տաճարի ներքևի մասը (13 շարք) կառուցվել է վարդագույն տուֆից։[15]

Վերակառուցման ընթացքում տաճարը գմբեթավորվել է։ Հին բազիլիկատիպ կառույցներին համապատասխանող մույթերը փոխարինվել են նոր, ավելի հզոր մույթերով։ Այդ բարդ եզրաձև ունեցող մույթերի վրա էլ հենվել են գմբեթակիր կամարները։ Վերջիններիս համապատասխան արվել են փոխուղղահայաց թաղեր, որոնք և արտաքին պատերին են փոխանցել գմբեթի հորիզոնական հակազդումները։ Գմբեթակիր կամարներից վերև տեղավորված է եղել բարձր փոխանցման գոտին, որը գմբեթատակ քառակուսին աստիճանաբար փոխանցում է բուն Տեկորի տաճարի (Y դ․) հատակագիծը գմբեթի հիմնատակը կազմող ութանիստին՝ կոնստրուկտիվ մի լուծում, որտեղ ակնհայտ է ժող․ ճարտ–յան մեջ մշակված ձևերի արձագանքը։[15]

Ստեղծված ութանիստ հիմքի վրա է հենվել գմբեթի կիսագունդը։ Տաճարի թաղային կոնստրուկցիաները արտաքինից պարփակվել են երկլանջ ծածկերով, որոնք կառույցի կենտր․ մասում հպվել են փոխանցման բարձր գոտին պարփակող խորանարդաձև ծավալին։[15]

Տաճարի արտաքին ծավալային հորինվածքը լիովին դրսևորում է ներքին կառուցվածքը։ Առավել ճոխ մշակում ունեն հս․ և արմ․ ճակատները իրենց շքամուտքերով, զույգ որմնասյուները կրում են միասնական խոյակներ՝ V դ․ հայկ․ ճարտ–յանը բնորոշ ականթաթերթերով։ խոյակներից բարձրացող պայտաձև կամարները և հատկապես մուտքերի շրջանակները քանդակազարդված են սահուն, ալիքաձև ոճավոր– ված տերևազարդերով։ Ոչ պակաս հարուստ հարդարված են սյունասրահների որմնասյուներն ու դրանց խարիսխները, լուսամուտների պսակները։ Հիմնական մոտիվներն են խաղողի որթատունկի գալարներն ու ողկույզները, բուսական ոճավորված զարդաձևերը, ընդ որում կան մոտիվներ, որոնք առաջին անգամ ի հայտ են գալիս այստեղ՝ Տ․ տ–ում։ Արմ․ ճակատի վերնամասում, փոքր խաչաձև լուսամուտի երկու կողմերում, քանդակված են մարդկանց (թերևս կտիտորների) կիսանդրիներ, իսկ վերևում՝ երկու սիրամարգեր, որոնք կտցահարում են գավաթից բարձրացող խաղողի ողկույզները։ Գլխավոր աբսիդը ծածկված է եղել որմնանկարներով, որոնք շատ վատ են պահպանվել։ [15]

Ունի քառակուսի հատակագիծ, գմբեթը հենվում է ներսից բարձրացող 4 քառակուսի հաստահեղույս, կամարակապ սյուների վրա: Շենքը ներքևի մասում շարված է վարդագույն տուֆով:[16]

Իր վեհ ու գեղեցիկ ոճով Տ տ շատ է տարբեր- վում Շիրակի պատմա-ճարտարապետա- կան մյուս հուշարձաններից: Ունի երեք մուտք' հս, արմ, հր:[16]

Շենքը ներսից ունեցել է որմնանկարներ:[16]

Formerly it was believed that the church was built as a basilica without a dome (possibly of pre-Christian origin and converted to a church by adding an apse) and that the dome was added later; as late as the seventh century according to some.[2]

According to current opinion, the church was build from the outset as a domed building with a "cross within a rectangular perimeter" plan.[2]

The earlier theory was derived mainly from observations of the pillars, now impossible to verify (although it is possible that something may remain below today's ground level). The change in hue between the lower and upper courses of stone, clearly visible on old photographs, was also said to indicate an alteration of the original design. However, there is not an obvious break in construction visible within the surviving fragments of the concrete core - perhaps this change of hue was decorative.[2]

The dome was supported on four thick pillars and had an unusual design - rather like a domed vault. There were no squinches or pendentives, and its lower part was a sort of trapezoidal pyramid shape (pierced by 4 windows) that formed a base for the cupola.[2]

The church originally had four entrances: one to the west, one to the south, and two to the north. At a later period these doors were closed off, except for the western most entrance on the northern side which was reduced in size. These doors were framed by visually powerful portals of horseshoe arches resting on jambs of twin embedded columns. These columns had carved capitals of jagged, and very stylised, acanthus leaves. The lintel over each door was carved with a strange, swirling palmette motif.[2]

All the larger windows were reduced in size at some distant period, possibly during the Bagratid restoration (the external pyramid roof of the dome probably also dates from this restoration).[2]

Oblong rooms flanked each side of the apse. The walls of these rooms extend outwards from the north and south facades, a feature that is also found on other early Armenian churches of this period. At the north-eastern corner of the church, set into the external wall of the northern of these rooms is a semicircular niche, probably a baptismal font.[2]

The church stood on a nine stepped base. Because this base is wider than the church, it used to be thought that a portico once ran around the outside of the church, supported on the pilasters and columns that are attached to the lower half of the facade. The position of the windows and the height of the north-eastern niche with its baptismal font tend to contradict that theory. The pilasters may just be decorative, a feature also found in Syrian architecture from this period. Another indication of possible Syrian influence is the moulded band that ran around the three facades and over the arches of the windows.[2]

Mnatsakanian, Stepan (1971). "Տեկորի տաճարի կտիտորական բարձրաքանդակը [The Ketitor Relief of the Tekor Church]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (4): 206–216.

Government House, Yerevan

https://www.gov.am/en/building/#

Elements of Medieval Armenian architecture and monumental sculpture were used by the author of decorative designs (Tekor, Dvin).

Դաստիարակված լինելով դասական ճարտարապետության լավագույն տրադիցիաներով, քաջ տիրապետելով համաշխարհային ճարտարապետության գանձերին, լավագույն գիտակ ճարտարապետական ձևերին, Թամանյանն ըստ արժանվույն գնահատեց հայ ճարտարապետական հուշարձանների ուժն ու թափը: Այդ հուշարձանների պատկառելի ավերակները մեծ հետաքրքրություն առաջացրին նրա մեջ: Երերույքում և Տեկորում, Զվարթնոցում ու այլ բազմաթիվ հուշարձաններում, Թամանյանը կարողացավ տեսնել այն բարձր գծերը, որոնք կապում են այդ հուշարձանները դասական աշխարհի` Հունաստանի և Հռոմի լավագույն ճարտարապետական կոթողների հետ:[22]

Syrian/Cappadocian

[edit]Հայտնի է, որ քրիստոնեությունը Հայաստան է թափանցել Սիրիայից: Մառը, ելնելով դրանից, Հայաստանի քրիստոնեական վաղ շրջանի բազիլիկային կառուցվածքները և հատկապես նրանց հարդարանքները համեմատում է սիրիական համանման հուշարձանների հետ և հայտնում այն միտքը, թե այդ կառուցվածքները (Երերուք, Տեկոր և այլն) հանդիսանում են 5-րդ դարի վերջի կամ 6-րդ դարի սկզբի գործեր և իրենց ընդհանուր հորինվածքով ու մանրամասերով կապված են «հայկական եկեղեցական կյանքի սիրիական հոսանքի հետ» և անվիճելիորեն ունեն «սիրիական ծագում»։ [1 Мар р Н. Я., Ереруйская базилика, армянский храм V—VI веков. ЗВ О имп. русского арх. общества, т. XVIII, С.-Петербург, 1908, стр. XIII.]; [Мар р Н. Я , Новые археологические данные о постройках типа Ереруйской базилики, ЗВО имп. русск. археолог, общества, том XIX, С.-Петербург, 1909, стр. 064, В. А. Миханкова, Николай Яковлевич Марр, М.-Л. 1935, 99—100 և այլն։][23]

Richard Krautheimer argued that the basilica, particularly its "the decorative details, including horseshoe arches, are so close to those of Cappadocian churches as to suggest the activity in Armenia of Cappadocian mason crews."[24][25]

Studies

[edit]Toramanian, Toros (1911). Պատմական հայ ճարտարապետութիւն: Ա: Տեկորի տաճարը (in Armenian). Tiflis: Hermes. archived PDF

Mapp Н․, Ереруйская базилика, Е․, 1968․ Ս․ Մնացական յան․[15]

1908թ. Ն. Մառը հատուկ գիտարշավ է կազմակերպել Տեկորի տաճարի հետազոտության համար, որին մասնակցել են Թ. Թորամանյանը, Ս. Պոլտարացկին, Ն. Տիխոնովը, Հ. Օրբելին եւ ուրիշներ: Նա Տեկոր է այցելել նաեւ 1909թ. եւ մանրամասն նկարագրել է տաճարը: Իսկ 1911թ. լույս է տեսել Թ. Թորամանյանի Տեկորին նվիրված մենագրությունը:[26]

Ֆրանսիացի ճարտարապետ Դեսիեն, որը 1839 թ սեպտեմբերին այստեղ ուսումնասիրություններ է կատարել, հատկապես ուշադրություն է դարձրել պայտաձև կամարների վրա ու հանգել այն եզրակացության, որ Տ տտիպիկ հայկական ոճի է:[16]

1907 թ. Նիկողայոս Մառը՝ առաջինն անդրադառնալով Երերույքի տաճարին, գրում է. “Եզրահանգում եմ. Երերույքի բազիլիկան, որ գտնվում է նույն իշխանական տոհմի տիրույթներում, կառուցվել է Կամսարականներից մեկի կողմից և այն ժամանակաշրջանում, երբ առաջ էր եկել Տեկորի տաճարի սկզբնական հենքը՝ Երերույքի տաճարի կրկնակը, ասել է թե՝ V դարի վերջին կամ VI դարի սկզբին” 2 : [2 Н. Марр. Ереруйкская базилика. Ереван, 1968, с. 28.][18]

1911 թ. Թորոս Թորամանյանը գրում է. “Ըստ իս՝ Տեկորի, Քասախի տաճարները պարզապէս հեթանոսական մեհեաններ են” [Թ. Թորամանյան. Տեկորի տաճարը, Թիֆլիս, 1911, էջ 77:][18]

https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03368777/

Patrick Donabédian. Yereruyk: A Site Rich in Enigmas and Promises. The Armenian-French Archaeological Mission of LA3M in Armenia (2009-2016). Pavel Avetisyan; Arsen Bobokhyan. Archaeology of Armenia in Regional Context. Proceedings of the International Conference Dedicated to the 60th Anniversary of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (July 9-11, 2019, Yerevan), Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, pp.342-365, 2021. ffhalshs-03368777f

A similar platform was present under another church, St. Sergius of Tekor, built in all probability a little earlier than Yereruyk, at the end of the 5th century (Donabédian 2008, 54– 57). / Donabédian P. 2008, L’âge d’or de l’architecture arménienne. VIIe siècle, Marseille: Parenthèses./

Located about 20 kilometres south-west of Yereruyk, now in Turkish territory and destroyed, Tekor had a remarkable structure for its time: an inscribed cross crowned by an archaic dome, but despite this difference, it had a close kinship with Yereruyk. Both were located on the lands of the Kamsarakan, a great Armenian dynasty of the Late Classical period and shared a series of features, both architectural and decorative (Donabédian 2014a, 252–253). / Donabédian P. 2014a, Ereruyk‘: nouvelles données sur l’histoire du site et de la basilique, in: Mardirossian A., Ouzounian A., Zuckerman C. (eds), Mélanges JeanPierre Mahé (Travaux et Mémoires 18), Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance, 241–284./

Tekor was named in its dedicatory inscription “martyrium of St. Sergius”. [...] It is highly plausible that, like Zvartnots, the great martyria of Tekor and Yereruyk, dedicated to the memory of particularly venerated saints, sheltered their relics. Other traits of kinship with Early Christian Syria, as well as with Asia Minor, including Cappadocia, can be seen at Yereruyk in the treatment of the facades, traits by which this basilica, together with Tekor, stands out from other churches in Armenia. This is the case of the continuous moulded strips, independent of any architectural element, which run horizontally through the building, and those that surround the windows to the bottom of their bay where they form two horizontal folds (Fig. 2/a). The triple window at the top of the western facade is also a common feature with Syria, where it is observed for example on the church of Baqirha (546). Lastly, a Greek inscription engraved on the southern facade of Yereruyk, on which we will return later, creates a precise link with a Syrian church.

Strzygowski 1918, pp. 335-341

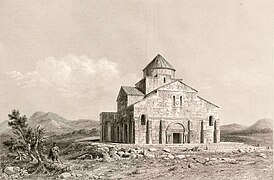

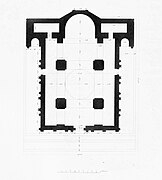

FIG. 9 The church of Tekor, reconstruction by T'oramanyan. (Donabedian 2013, p. 23). [DONABEDIAN, P., "Les debuts de 1'architecture chrétienne en Orient: Les premieres églises ä coupole d'Armenie", in: L' Archeologie du báti en Europe = Apxeo.nozin doMOÖydieHUumea Ceponu, L. Iakovleva, O. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, F. Djindjian (eds.), Kiev 2013, pp. 346-364.] FIG. 33 Tekor - plan. (STRZYGOWSKI 1918, p. 336). [STRZYGOWSKI, J., Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa, 2 vols., Vienna 1918. ] https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/strzygowski1918ga https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/strzygowski1918bd1/0352/image,info

https://www.persee.fr/doc/rebyz_0766-5598_1985_num_43_1_2179_t1_0305_0000_2 Chapter II. The church of Tekor, the current Digor (p. 20-27). - This building was it half a century ago as a cross inscribed on four free supports of the dome and peripheral gallery. The architect T'oramanyan indulged, in his opinion, in speculations- ingenious historical tions to make it a pagan temple transformed into a basilica, to which would have been added later a dome. N. Marr and Strzygowski for their part they dated it to the end of the 5 ° century according to the analysis of a reused inscription. All these work was done in the absence of excavations and gave rise to some disputes. Nevertheless the author adopts the theory of T'oramanyan and the dating of Marr without discussion, without taking into account the contrary opinion of Mr. Hasrat'yan or the existence from a typologically very close monument, the inscribed cross of Cromi in Georgia, although dated from the 6th century. If the hypotheses taken up by the author are plausible, it does not seem to us however, it is not very prudent to take them for granted and use them as a basis for reference.

In 2015 Pargev Frankian of the Research on Armenian Architecture created a digital reconstruction of the church.[27]

https://archive.ph/BgU3c

Inscription

[edit]File:Տեկորի տաճարի արձանագրությունը, 480-ական թթ., ՀՊԹ.jpg

Michael E. Stone: I should say that the oldest Armenian inscription known before the Sinai discoveries was from the very end of the fi fth century. It was on a basilica in Tekor, now in the Kars province of Turkey. The inscription is lost, but photographs of it survive.2[28]

An additional point which makes the dating of the earliest of the Sinai inscriptions difficult is the fact that we have no clearly dated Armenian inscriptions of the 6th century. Armenian writing commenced only in the 5th century, and only one single inscription, from the church of Tekor, is known and dated on the basis of the historical personages mentioned to the end of the 5th century (Yosép'ian 1913: 5-6).[29] [Yovsepian, G. The Art of Writing Among the Armenians, Vagharshapat, 1913] [3][4]

As for the epigraphic evidence, few Armenian inscriptions survive from these early centuries. The oldest is the late fifth-century inscription of the Tekor basilica.[30]

Acharian: oldest (p. 476) http://serials.flib.sci.am/Founders/Hayoc%20grer-%20Acharyan/book/index.html#page/480/mode/1up

- Acharian, Hrachia (1984). Հայոց գրերը [The Armenian Letters] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. (archived)

This inscription was the oldest known example of Armenian lettering and ran, unusually, from bottom to top.[2]

Տ-ի վրա պահպանված վիմագրերը հայկական գրերի (երկաթագիր) հնագույն նմուշներ են (5-րդ դ):[16]

Տեկորի տաճարը չափազանց արժեքավոր էր հայ մշակույթի համար և նրանով, որ հուշարձանի շինարարական արձանագրությունը, փորագրված Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի մահվանից մոտ երեք տասնամյակ հետո, մեզ հասած հայերեն ամենահին գրությունն էր և հավաստի պատկերացում էր տալիս մեսրոպաստեղծ այբուբենի տառաձևերի մասին:[3]

Տեկորի Ս. Երրորդություն վանքի այս արձանագրությունը մեզ հասած հայերեն ամենահին գրությունն է և պատկերացում է տալիս մեսրոպյան այբուբենի նախնական տառաձևերի մասին:[6]

Ghafadarian, Karo (1962). "Տեկորի տաճարի V դարի հայերեն արձանագրությունը և Մեսրոպյան այբուբենի առաջին տառաձևերը [The Armenian Inscription on the Cathedral of Tekor and the Initial Forms of the Mesropian Alphabet]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (2): 39–54.

Mouradian, Paruir (2007). "Ո՞վ է Տեկորի արձանագրության հազարապետ Մանանը [Who is the hazarapet Manan in the inscription of Tekor]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 63 (9): 85–88.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3591380 A Corpus of Early Medieval Armenian Inscriptions Timothy Greenwood

https://bpb-us-e2.wpmucdn.com/sites.uci.edu/dist/c/347/files/2020/01/e-sasanika3-Greenwood.pdf Sasanian Reflections inArmenian Sources TIM GREENWOOD

https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/42649319/DK_art_Alubm_Arm_Paleo___preface___biblio_-libre.pdf?1455384179=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DDickran_Kouymjian_History_of_Armenian_Pa.pdf&Expires=1699283633&Signature=EMch5pBuRMM2HP07zDpa2hJxOSqBRINJkPnMqEp31qg-PmD9lO~bR1DON0lAq0gpvM9SQhCyOSKhK2rdBBBz1grwgOHrlpI-qh5P1z6ZDVQJCH-l023HUjwWR3CJFxBcpS6G8CwyIPGNmD4mYDJtxkC3STzeWiHmTBkWFq5dlu0PWSh3aq-QQWLu1ti6IpwTvmPxSxuyuUjYR2cWadXY2kQZXmRtpIDSho-9X6PJsJgfeOCFqnyd~KkjH6tlm7z-v70T3niL2QJJBRQ6A~rP3L6q~U7bTqP2ZS3oihtGN6~hKzSmWW3N15xvQIf~ZHMMMj4MgskYH1O67BnjnDmQxA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA Album of Armenian Paleography Michael E. Stone Dickran Kouymjian Henning Lehmann

https://journals.ysu.am/index.php/arm-fol-angl/article/view/Vol.15_No.2_2019_pp.135-154 https://journals.ysu.am/index.php/arm-fol-angl/article/download/Vol.15_No.2_2019_pp.135-154/Vol.15_No.2_2019_pp.135-154.pdf/7406 The other inscriptions with which King Gagik would have been familiar were those on Armenian churches, much shorter than that of Meher Kapısı. The oldest known Armenian monumental inscription is fifth-century. It is now lost, so is known only through reports, photographs, and a cast that was made in 1912 and that is in Erevan. It was on a lintel on the west door of the church at Tekor (Digor), in north-east Armenia. The two lowest of its five lines record Sahak Kamsarakan’s building a martyrium of Saint Sergius. It was to intercede for himself and for his family (line 3). The upper three lines say that the place itself had been founded by five other people: Tayron, a priest of the monastery; Manon, a hazarapet; Uran, a Roman; Yohan, the Catholicos; and Yohan the bishop of the Arsharunik´ (Durand, Rapti and Giovannoni 2007:61-62). [Durand, J., Rapti, R., and Giovannoni, D. (eds.). (2007) Armenia Sacra: Mémoire chrétienne des Arméniens (IVe-XVIIIe siècle). Paris: Musée du Louvre.]

The church is dated back to the 5th century, around the 480s, due to the names mentioned in an inscription that has not survived to our time[4]

Elizabeth Redgate: The oldest known Armenian monumental inscription is fifth-century. It is now lost, so is known only through reports, photographs, and a cast that was made in 1912 and that is in Erevan. It was on a lintel on the west door of the church at Tekor (Digor), in north-east Armenia. The two lowest of its five lines record Sahak Kamsarakan’s building a martyrium of Saint Sergius. It was to intercede for himself and for his family (line 3). The upper three lines say that the place itself had been founded by five other people: Tayron, a priest of the monastery; Manon, a hazarapet; Uran, a Roman; Yohan, the Catholicos; and Yohan the bishop of the Arsharunik´ (Durand, Rapti and Giovannoni 2007:61-62). [Durand, J., Rapti, R., and Giovannoni, D. (eds.). (2007) Armenia Sacra: Mémoire chrétienne des Arméniens (IVe-XVIIIe siècle). Paris: Musée du Louvre.][31]

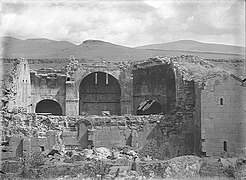

Destruction and current state

[edit]The church survived largely intact until the early 20th century. It wad abandoned in 1906.[8] It suffered significant damage in an earthquake on August 1, 1912,[26][4][b] when its dome, most of the roof, and much of the southern façade collapsed.[2][15][6] Dickran Kouymjian wrote that even in ruins, Tekor was "still massive and impressive."[8] In August 1920,[39] just before the Turkish–Armenian War, Ashkharbek Kalantar led the last Armenian expedition to Tekor and documented its state.[40] He wrote that the collapsed church "presents a pitiful picture" and that the "image is so disturbing that at first one needs some time to recover from the shock."[39][2]

The church was further damaged by an earthquake on May 1, 1935[26][37][c] and was deliberately targeted by the Turkish military during artillery exercises in 1956.[42][43] The facing stones of what remained of the church were removed by the 1960s. Nicole and Jean-Michel Thierry, who visited in 1964, reported that the church was "almost entirely leveled" and it had lost all its facing stones.[44] An American couple photographed the ruins in 1966, showing its walls entirely stripped of facing stones.[45]

In 1964 the Thierrys did not notice "traces of reuse in modern houses" during their self-described "superficial" field work,[44] but according to Murad Hasratyan and Samvel Karapetyan, under Turkish control, its stones were gradually removed by local peasants and used as construction material.[6][9][d] Hasratyan noted that its polished and sculpted stones can be found in the walls of local houses and barns.[e] Steven Sim who visited in the 1980s, reported that according to locals, its facing stones were used in the 1960s for the construction of the Digor town hall, which was itself was demolished in the 1970s.[2] According to Kouymjian, upon his visit in 1999, "there were only fragments, chunks of masonry walls" remaining.[8] Sim argues that its present state is "mostly the work of man rather than earthquakes."[2]

According to art historian Karen Matevosyan, who visited in 2013, the ruins form part of a local Kurdish man's house.[46] A Turkish researcher wrote in 2020 that villagers store poultry and other belongings in the church's remnants.[47] An Armenian art historian, who visited in 2022 noted that the site is filled with litter.[48]

A Turkish survey in 2014 noted that the church has "reached our time in a dilapidated state, with some of its eastern and northern walls standing without facing stones". The survey drew its plan and section sketches, took measurements and photographs.[4] In October 2019, the Kars Regional Cultural Heritage Preservation Board (under the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism) decided to register the church as an immovable cultural property. It noted that the property is "currently in an unprotected state and is in quite a neglected condition."[49]

only survived to the present day with the apse section and the northern body walls. The outer side of the church's body walls is constructed using regular cut basalt stones, while the inner part is built using rubble stone filling.[49]

The fact that only a few years ago it was standing completely intact and that now due to our carelessness half of it is down, scattering numerous pieces inside and out, allowing them to be lost for ever, cannot have any justification and permits no consolation. Half of the southern wall has fallen down; the height is up to the arches of the covered windows. Most of the stones above the bases of the pillars have fallen. The columns of that side are also down, as well as the whole roof with the dome. The entire eastern wall with the apse and two chapels has remained intact, along with the northern side, the nave and the pillars. The west wall has lost its top, the upper part of the left corner and its facing stones, with only the clay layer being left. Fallen stones heap up chaotically inside the church and along the outer southern side, leaving a disorderly and desolate scene. From the stricken southern side it can be seen that the frail beams erected horizontally along the walls in two rows have furthered the destruction process. The southern wall has tumbled down along that line. Those beams can be seen in the chapels, deep empty tracks being left in the walls. The part of the roof on the northern apse, which has survived up to now, and the upper semicircular part of the western wall are in a very unstable position and in danger of falling down. The same holds for the remaining southern wall, which has large cracks. The northern wall of the church above the doors is damaged by bullets. The signs are rather new. Probably Turkish soldiers were amusing themselves here![39]

The church has four doors: one to the west, one to the south and two to the north. All were closed off long ago with rather large stones except for the western door on the northern side. The remaining open door is lower; a large stone has been fixed in below the lintel. Apart from the doors, all middle-size and large windows were also closed on three sides with good solid masonry of finished stones. This is old work, as is shown from the inscription on the inner face of the side of one of the northern windows: A.D. 1049. The window of the apse has been also made narrower and smaller. Only the small upper windows were left open. They are situated in pairs higher than the upper cornice on three sides, in the centers of the walls above the pediments. Narrow windows are left open as well. Traces of frescos and inscriptions can be seen. The church of Tekor is built on a slope, in the crest of a hill stretching to the south. A narrow, elongated Urartian fortress stands right in front of the church, slightly to the east on the edge of the crest. The remnants of all four walls are visible, the entrance from the west, has had a path from the east. There are remnants of numerous buildings, especially on the south slope of the hill. The stones of the walls, up to 2-4 m in size, are unprocessed. It is a structure of an ancient Urartian type.[39]

Maranci

[edit]Maranci, Christina (2001). Medieval Armenian Architecture: Constructions of Race and Nation. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 9042909390.

The church of Tekor is located in the district of Kars, close to the pre- sent-day eastern border of Turkey (Fig. 19, 20). Today, only remnants of the wall still stand.18 However, its architectural form can still be dis- cerned: a domed, three-aisled basilica, terminating in a semi-circular apse flanked by two chambers. Serious questions surround the date and building phases of Tekor. Three inscriptions on the west portal provide ample but confusing information.19 One inscription, located on the west façade, indicates that Sahak Kamsarakan built the church (identified as St. Sergius) in the fifth century. The other two data from the tenth cen- try and refer to renovations under the Bagratid dynasty. While most scholars agree on a fifth-century foundation date forTekor, there is no consensus on its original appearance, and many believe that the dome was a seventh-century addition.[50]

In his book, The Temple of Tekor,20 T'oramanyan provided his own hypothesis concerning the chronology and building phases of the church. He proposed that the present structure was a conglomerate of several periods of construction, ranging from the pre-Christian period to the tenth century. The first church at Tekor, according to Toramanyan, dated to the fourth century and consisted of a rectangular structure terminating in a square apse (Fig. 21). A century later, he suggested, the apse was flanked with side chambers and a peristyle portico was constructed (Fig. 22).21[50]

18 Considerable damage to the church occurred during the earthquakes of 1911 and 1935. 19 The first, which is dated 1008, recounts the lifting of taxes by queen Katramide, wife of king Gagik ( 990-1020 ). The second is dated 1014, and indicates that King Ašot also lifted taxes and mentions (in what could be a later addition to the text) the construction of Surb Sargis (Sergius). The third, which most likely dates from the 490s, relates that Sahak Kamsarakan constructed the martyrium of St. Sargis. However, this inscription only makes sense when read starting with the bottom line and working upwards, as Marr pointed out. For more discussion of the problems in the dedication and chronology of Tekor, as well as further references, see Armen Khatchatrian, L'architecture arménienne du IVe au VIe siècles, Paris, 1971. 20 Tekori tačarə, Tiflis, 1911. See also the article by the same name in Axurean, 1909, May, no. 39. 21 To be more precise, T'oramanyan specifies that the side chambers were built first, and that the portico was built very soon afterward.[50]

As neither square apse nor portico exist in the current church, T'ora- many an's claims require some justification. Evidence for a portico, he argued, can be found through an inspection of the monument.22 Toramanyan suggested that Thor's broad, stepped platform provided an appropriate base for a wrap-around portico. Examining the exterior walls, Toramanyan noted the large size and regular intervals of the attached piers and interpreted them as responses for vaults of a portico. Further, the horizontal profiling of the exterior walls, according to T'oramanyan, functioned to mask the joint line which was exposed after the vaults were removed.[51]

22 The evidence I present below represents only a fraction of the scope of T'oramanyan actual argument. However, I feel that I have provided a representative sample of his claims, both in terms of content and approach.[51]

Certainly, porticos were common elements in both Syrian and Armenian architecture.23 However, T‘oramanyan’s reasoning does not provide convincing evidence of a portico at Tekor.24 The presence of stepped foundation and attached piers, for example, cannot confirm a portico: there are several Armenian churches with these elements and yet no portico, such as the Cathedral of Ejmiacin,25 Zvart‘noc‘, and the Cathedral of Ani.[52]

Large attached piers decorate contemporary churches in northern Syria: both Qal'at Si'man and the east end of Qalb Lozeh are ornamented thus, but in neither case were these features part of a portico system.26 Most problematic, however, is T'oramanyan's proposal for a "peristyle" structure -- a form which finds no counterparts in the Christian East. The square apse proposed by Toramanyan is equally difficult to support. In the absence of archaeological evidence, the author built upon his previous claim, arguing that the present semi-circular apse could not have co-existed with a portico. Such a pairing, he wrote, "would not only have been unpardonably ugly"27 but it would also be "difficult to construct, since there would have been no free space at the east end" 28 This is of course circular reasoning.29[52]

23 The basilica of Ereruyk*, built in the fifth or early sixth century, possessed one (now destroyed). Early Syrian churches, such as Turmanin and Qalb Lozeh, also featured porticos. One could hypothesize, based on these examples, the presence of such an ele- ment at Tekor. 24 However, T'oramanyan does find material evidence which supports his thesis. He notes for example the differences in the thickness between the upper and lower wall sections as well as a difference in the masonry coursing on the interior and exterior walls. The latter suggested to him the addition of a wall on the lower level in order to sup- port the vaults of a portico. On the north side, T'oramanyan detected the remains of the springing of two arches from the attached columns, which he supposes were the base of diaphragm arches for the portico vaults. Further, on the eastern end, he found a base of a capital, which suggested to him that the portico wrapped around the building completely. Jean-Michel Thierry and Patrick Donabédian believe that the engaged columns were simply decorative (J.-M. Thierry and P. Donabédian, Armenian Art, New York, 1987, pp. 584-585 ). 25 However, T'oramanyan believed the cathedral to have had a portico, although to my knowledge there is no physical evidence for it. 26 See R. Krautheimer, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, pp. 144-155 . 27 Materials, 1, p. 196. 28 Ibid. 29 T'oramanyan also does not take into account the shape of the stepped foundation. In its eastern end, it follows the outline of the polygonal apse. Since no mention is made of alteration to the masonry of this area (which would be an arduous and unnecessary task) we may assume that the stepped foundation is contemporaneous with the apse. T'oramanyan also argues that the placement of the semi-circular apse, which projects slightly from the eastern wall, reveals its later date. In its location, it "breaks the rules" of Armenian archi- tecture, in which "the apse is either completely articulated on the exterior, or completely inscribed." Its "in-between" position thus proves that it was made to fit within an already enclosed area. While T'oramanyan could not have known it at the time, his "rule" of the position of the eastern apse is broken in at least one instance. At the fifth-century cathedral of Dvin, excavated in the 1950s, we find an example closely resembling that of Tekor -- a "semi-inscribed" eastern apse flanked by two transverse side chambers.[52]

Toramanyan also held that semi-circular examples were not indige- nous to Armenia, but imported from the West.30 Churches in Armenia, he believed, were initially furnished with a central altar rather than an eastern apse. In the fifth century, according to the author, the Church enforced a uniformity of ritual on the East which generated changes in liturgy and architecture. The supposed arrival of the eastern apse in Armenia is viewed in conjunction with these events. One could approach this thesis in several ways, but one may simply point to the hypogeum of Acc' near Mount Aragac in Armenia. The sub- terranean, cruciform chamber terminates in a horseshoe apse. T'ora- manyan did not know the hypogeum, which was excavated in the 1970s; however, it presents a counterexample to his thesis: a fourth-century monument with a semi-circular apse.31[53]

- III. The Dome

The last section of T'oramanyan's article considers the dome of Tekor. According to the author, between the fifth and seventh centuries the four central piers of the church were enlarged to support a square drum, on which rested a stone dome (Fig. 23). To prove his point, Toramanyan rightly focused on the irregularity of the pier sections as well as the lack of uniformity in the decoration of the bases; both of which suggest enlargements of previously smaller piers (see Fig. 19).32[53]

Toramanyan believed that Tekor possessed the first stone dome in Armenia. Comparing it to seventh-century examples, he noted the unusual quality of its construction, which is conical on the interior and cubic on the exterior. This form, T'oramanyan argued, imitated the[53]

1998

[edit]- Maranci, Christina (1998). Medieval Armenian Architecture in historiography: Josef Strygowski and His Legacy (PhD thesis). Princeton University. OCLC 40827094.

Schnaase appears to conclude here that all Armenian domes were a single, conical shell. However, as we know, they are generally spherical on the inside, surmounted by a conical roof.66 The explanation for his faulty generalization may be connected to the sources at hand: most of the images of Armenian churches were exterior views, which only would have shown the conical roof. Further, one of the only interior illustrations was Charles Texier's drawing of Tekor, which features an unusual dome that rises from the base of a drum in a conical, rather than spherical shape (fig. 13).[54]

T'oramanyan's best-known and most important contributions are his hypothetical reconstructions. His publications on Zvart'noc*, Ejmiacin, and Tekor, all written in the first two decades of the twentieth century, feature the same approach: a close physical inspection of the monument. accompanied by a proposal-- sometimes very bold-- of its original phase or phases. In this section, we will focus on his reconstructions of Ejmiacin and Tekor, which, although lesser known than that of Zvart'noc*, reveal much more about his beliefs regarding the origins of Armenian architecture.[55]

A. Tekor The church of Tekor is located in the district of Kars, close to the present-day eastern border of Turkey (fig. 3, 4). Today, only remnants of the wall are left standing after earthquakes from 1911 and 1935. However, its architectural form can still be discerned: a domed, three-aisled basilica, terminating in a semi-circular apse flanked by two chambers. Serious questions surround the date and building phases of Tekor. Three inscriptions on the west portal provide ample, but confusing information.20[55]

20 There are three inscriptions, which are all located on the west portal of the church. The first, which is dated 1008, recounts the lifting of taxes by queen Katramide, wife of king Gagik ( 990-1020 ). The second is dated 1014, and tell show King Asot also lifted taxes and mentions (in what could be a later addition to the text) the construction (šinut'yun: zhumhu) of Surb Sargis (Sergius). The third, which is not securely dated (but purports to be fifth century) relates that Sahak Kamsarakan constructed the martyrium of St. Sargis. However, this inscription only makes sense when read starting with the bottom line and working upwards, as Marr had pointed out. For more discussion of the problems in the dedication and chronology of Tekor, as well as further reference, see Armen Khachatryan, L'architecture arménienne du Vie au VI siècles, Paris, 1971.[55]

While we cannot go into the intricacies of the epigraphic evidence here, we should note that one of[55]

the inscriptions indicates that Sahak Kamsarakan built the church of St. Sergius in the fifth century. The other two date from the tenth century, and refer to rebuildings by the Bagratid queen Katramide. While most scholars agree on a fifth-century foundation date for Tekor, there is no consensus on its original appearance. Most scholars for example. believe that the dome was a seventh-century addition. In his article, "The church óf Tekor",21 T'oramanyan provides his own hypothesis concerning the chronology and building sequences of the church. He proposed that the present structure was a conglomerate of several phases of construction, ranging from the pre-Christian period to the tenth century. In the following section, we shall consider these phases, paying special attention to a theme which is predominant in T'oramanyan's work: the influence of classical (i.e. Greco-Roman) architecture on Armenia.[56]

We shall begin with the earliest phase and work forward. According to T'oramanyan, the first church phase at Tekor dated to the fourth century and consisted of a simple rectangle terminating in a square apse (fig. 5). At a subsequent time, probably in the fifth century, the apse was flanked by the two side chambers and a portico, which surrounded all sides (fig. 6). 22 Thus, in a comparison of the present structure with this phase, there are several changes; the square apse was replaced by the semi-circular one, the portico was removed, and the dome was added.[56]

T'oramanyan gives a variety of reasons for his thesis.23 In some cases, he argues from surrounding elements. The presence of the stepped foundation, for example, was built to accommodate a portico. Further, because of their large size and regular intervals, he believes that the attached piers must have performed a function, rather than just being decorative. The cornice, which encircles the building, provided T'oramanyan with further proof: he believes that it was placed there to "mask" the joint line where the portico vaults were removed. There are certainly problems with T'oramanyan's argument. In order, for example, to accept that the cornice masked the remains of the portico, one must first believe that it existed. The presence of a stepped foundation and large attached piers also cannot confirm a portico: there are several Armenian churches with stepped foundations and no portico, such as the Cathedral of Ejmiacin,24 Zvart'noc', and the Cathedral of Ani. Further, large attached piers make up part of the decorative vocabulary of contemporary churches in nearby northern Syria: very large pilasters decorated the exteriors of both Qal'at Si'man and the east end of Qalb Lozeh, but in neither case were these features part of a portico system, 25[57]

However, T'oramanyan does find material evidence which supports his thesis. He notes for example the differences in the thickness between the upper and lower wall sections as well as a difference in the masonry coursing on the interior and exterior walls. The latter suggested to him the addition of a wall on the lower level in order to support[57]

[MORE to p. 57]

It should not be inferred, however, that T'oramanyan ignores the idea of indigenous traditions. Frequently in his discussion of the early churches, he speaks of a mixture of Roman and local forms. The remnants of a cornice at the Cathedral of Ejmiacin, for example, offer T'oramanyan the opportunity to see "what harmony was commanded by the Romans in the Armenian style." This harmony (ubpqwzuw4) is also evident at Tekor, which represents, in the decoration and construction of its earliest phase, "a harmonious mixture of Armenian and Roman architecture." But this mixture arises, for T'oramanyan, out of a local imitation of Roman style.[58]

T'oramanyan posits that sometime between the fifth century and seventh century, an increased knowledge of stonework led to the construction of stone domes. To illustrate this, it will be remembered, he turns to the church of Tekor. Its unusual cubical drum and conical interior led T'oramanyan to believe that it was an imitation of a dome in wood. Thus, T'oramanyan dates the construction of Tekor's dome to after the wooden dome of the Cathedral of Ejmiacin in the fifth century and before the domed churches of the seventh century 57[59]

The early dates of Ereruyk*, K'asal and other basilicas are not the only proof of an initial basilican period in Armenia. Domed longitudinal structures (such as those we just examined) provide further hints. A number of them appear to be of two separate building periods, consisting of a basilican phase followed by a domed phase. The best known example is the church at Tekor (Chapter Two, figs. 3, 4).59 Located south of Ani, Tekor was initially constructed as a three-aisled basilica flanked at the north and south by porticoes. By the seventh century (perhaps earlier?) the four piers were enlarged in order to carry a dome and transverse barrel vault.[60]

Strzygowski first considers the diffusion of barrel vaults through a comparison of the fifth-century Armenian church of Tekor with the Visigothic church of San Juan de Baños in Palencia, Spain.63 Although altered by a subsequent restoration, the plan of San Juan by Alvarez is still largely accepted (fig. 25). The original church consists of a three aisled core, the central of which terminates in a rectangular apse. The lateral aisles, however, do not flank it; instead, they wing away from the center in parallel chambers. Alvarez further hypothesized a columnar portico surrounding its west, north, and south sides. Strzygowski compares this layout to T'oramanyan's plan of Tekor (Chap. 2, fig. 4). Strzygowski claims that the churches share a square apse and unusually large, rectangular side chambers. He also cites the concurrence of a columnar portico and horseshoe arches. The concurrence of these features lead him to postulate a diffusion from Tekor to San Juan de Baños.[61]

A number of factors weaken Strzygowski's thesis. First, there are several unresolved questions regarding the building phases of Tekor, making it an unstable point of comparison.66 [66 = The building phases present the greatest problem. While T'oramanyan proposed three building phases, a pre-Christian, a basilican, and a domed building, the current opinion of some scholars (Sahinyan, Thierry and Donabedian) is that the initial and only building phase was the current domed structure. This thesis, however, does not satisfactorily explain the altered character of the pier bases, which appear, as T'oramanyan noted, to have been enlarged at some point, suggesting the quite standard practice of adding domes to basilicas.][62]

Very little, then, encourages a direct connection between Tekor and San Juan de Baños.[63]

Simultaneously, however, there occurred another development-- the emergence of the domed-centrally planned church in the sixth-seventh centuries. For Xalpaxc'yan, the churches of Hrip'sime, Ojun, and Mastara marked the formation of a "well-developed" national architecture, which would exert an influence on that of later periods. Where did these structures come from? According to Xalpaxc'yan, they find their ancestors in the popular domestic dwelling, or glxatun, found in Armenia (and much of the Caucasus, Near East, and Central Asia)160.[65] Constructed of wood, these structures usually consist of a single, square chamber, topped with a very characteristic roof: a system of wooden frames continuously corbelled until only a small smoke-hole, or erdik, remains open at the top. Generally, the roof is supported by four piers (fig. 24). The perishable character of wood has meant that no pre- modern structures of this sort survive, however, the prevalence of the glxatun as a mode of habitation, particularly in rural areas, as well as other evidence, has suggested to many scholars its existence during the Middle Ages. For Xalpaxč'yan, proof of this hypothesis is found in the dome of Tekor. This structure, which Xalpaxč'yan considers among the oldest stone domes in Armenia, is sloped inwards on the sides, gradually narrowing to form a pyramidal, rather than cylindrical drum. Xalpaxčyan argues that this construction, which he refers to as corbelling, "is exactly the same as in the popular dwellings". Thus, he concludes, in Tekor we find a transitional monument, which signals the roots of the Armenian dome in the glxatun type. Xalpaxčyan finds further evidence in the cathedral of Ejmiacin. Agreeing with Alexander Sahinyan, he believes that the fifth-century phase of the cathedral differed little from its present state: a square chamber with axial apses divided by four central piers supporting a dome. Xalpaxc'yan considers the account of Sebeos, who tells us that the stone dome of the cathedral replaced the original wooden dome. The early occurrence of wooden dome, then, as well as the use of four supports, further allows Xalpaxcyan to liken this church type with the glxatun.[66]

Varazdat harutyunyan. Further, the whole architectural layout of Tekor, with its dome atop a three-aisled basilica, provided the model for the domed basilica. Although not created ex novo, as a "pure construction", 181 in its conglomerate building phases, it nevertheless provided subsequent builders with a new model. Tekor thus assumes a central place in the development of Armenian architecture, for, as Harut'yunyan writes, "in this monument began the progress of the monumental dome" which was followed by its "logical integration" into the composition of the domed basilica. Among the examples of Tekor's progeny, according to Harut'yunyan, are the seventh-century churches of Ojun, Gayane, Mren, and Bagavan.182[67]

major

[edit]- Maranci, Christina (2018). The Art of Armenia: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. XXX. ISBN 978-0190269005.

- Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan [in Armenian] (2009). Հայոց պաշտամունքային վայրեր [Armenian places of worship] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Publishing. pp. XXX. ISBN 978-5-8084-1068-8.

- Khalpakhchian, O. Kh. [in Russian] (1962). "Армянская ССР [Armenian SSR]". Искусство стран и народов мира. 1: Австралия - Египет [Arts of the Countries and Peoples of the World. Vol. 1: Australia - Egypt] (in Russian). Moscow: Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya. pp. 100–133.

Hovhannes Khalpakhchian

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

Harutyunyan, Varazdat (1992). Հայկական ճարտարապետության պատմություն [History of Armenian Architecture] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Luys. ISBN 5-545-00215-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2022.

Տեկորի եկեղեցի 71, 73, 75, 92, 97, 100, 109, 111, 113, 118- 119

- Thierry, Jean-Michel; Donabédian, Patrick (1989) [1987]. Armenian Art. Translated by Celestine Dars. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-0625-2.

TEKOR page 165: Saint Sergius or Holy Trinity pages 55 to 60, 62, 70, 495, 502, 514, 517, 522, 529, 545, 584[a], 585

https://archive.org/details/thierry-1989-armenian-art/page/55/mode/1up?view=theater&q=tekor

The cathedral at Ejmiacin and the church at Tekor are the only two large buildings with cupolas that can be said to belong, with some reservations, to the paleo-Christian age.

https://archive.org/details/thierry-1989-armenian-art/page/56/mode/1up?view=theater&q=tekor

Patrick Donabédian https://archive.org/details/thierry-1989-armenian-art/page/516/mode/1up?view=theater

By the late fifth or early sixth century the basilica of Tekor was modified by the addition of a dome over the central bay of the nave. In the seventh century basilicas were built like Tekor with cupolas resting on four central and free-standing pillars (Odzoun, Bagavan, Mren, Gayane and Talin).

John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin

The Surb Sargis (St. Sergei’s) church in Tekor, in the Shirak region of the present-day Turkey, is nowadays in total ruin. Fortunately, before its destruction by the 1911 earthquake, it had been extensively studied (e.g. by T. Toramanian and J. Strzygowski) and the documentation preserved allows us to treat it as one of the most important early-Christian buildings in both Armenia and the whole Orbis Christianus (Fig. 1-3).

http://czasopisma.kul.pl/vp/article/view/3516

Tekor

- 270

https://books.google.am/books?id=B5RQAQAAMAAJ&pg=270

The church of Dighour, though in Armenia, is to all in- tents and purposes of the Byzantine family. The dome rests on central mass-piers; the bema has no passages to the prothesis and diaconicon. The most remarkable feature in this building is the protrusion of the two latter chapels, and the niche formed on the exterior west side. This has no practical use: nor, as it would seem, any symbolical meaning: I think it a mere determination to Armenianize in the matter of the niche. The western façade is remark- ably broad : there is a couplet in the gable : at the west end of, if we may so call them, the aisles, are single lights. All the western buttresses are of two stages : most exactly re- sembling those of First Pointed date in England. Over the three doors is an entablature supported by quasi-Corinthian pillars, an arrangement which seems to have given great satisfaction to the architect, as he has repeated it in the bays opposite the western mass-piers, where there are no doors. The other buttresses are semicircular pilasters, not unlike some Romanesque examples in England. A ground-plan of this church has been given at p. 229°.

- 298

I now pass to those churches which unite in themselves Armenian and Byzantine arrangement. Of some of these I have already spoken; for example, Ani, Gagra, and Dighour ; they, however, seemed more properly to belong to Constanti- nopolitan art.

Dickran Kouymjian[37]

Type:

Three aisled basilica with dome.[37]

- Location

In the region of Kars, Western Turkey.[37]

- Date

IV or V c. foundations. VI or VII present form.[37]

- Evidence For Date

Stylobate indicates very early origins for foundation. Inscription at Western entrance.[37]

- Important Details

Free standing T-shaped piers and dome added in the 6th or 7th c. Portico on three sides. Small apse at end of north porch.[37]

- State of Preservation

Now completely destroyed. In photos taken before World War I, it was standing complete with dome.[37]

- Reconstructions

Conversion from a basilica to a domed basilica in 6th or 7th c. Dome exterior reconstructed in 10th century.[37]

- Summary

The Church of St. Sarkiss, Tekor is located in the village of the same name in Turkey, southwest of the ruined Armenian city of Ani (coord. 40-24 / 43-25). It is dated to the 5th century on the basis of archaeological evidence and its architectural style. There are also three inscriptions on the tympanum of the west portal that provide historical information on the Church. The inscriptions are considered copies of the original ones; however, are the subject of controversy regarding the name and dating of the original form of the Church.[37]

The updated inscription is by the 5th century Prince Sahak Kamsarakan and states that he was the donor of "This Martrium of S. Sargis". It also includes the names of a contemporary bishop Hovhannes of Arsarunik' and the Catholicos Hovhannes. Most scholars accept the inscription as an authentic late 5th century document but the paleography indicates otherwise (Hovsepian and T'oramanyan). T'oramanyan also considers the inscription to refer to another Church, a smaller, more appropriate form for a moratorium. An added problem is that the Church is referred to in the inscription of 1008 by Queen Katranide, King Gagik I's wife, as S. Erordut'iwn (Holy Trinity), not S. Sargis. According to Marr, this means that Tekor had a change of name, while T'oramanyan thinks two different Churches are being mentioned. The third inscription is by Asot and dated 1014.[37]

Preserved until 1911 when the cupola collapsed, Tekor was severely damaged by an earthquake in 1935. In 1964 (according to the Thierrys, 1965), all the facing stones had been removed from the site of the ruined Church. There was no evidence of their reuse on neighboring structures, as is often the case in Turkey. Tekor was originally a construction in basilican form with two pairs of cruciform pillars on the interior supporting cruciform vaults. According to Tíormanian, it was originally a pagan monument that had been converted into a Christian edifice. Shortly after its construction in the late 5th century, significant changes were made to the structure. A cupola was constructed over the enlarged square bay. A semicircular apse and two transversal chambers were built at the east end. The chambers projected to the north and south and abutted the portico.[37]

The stone dome of Tekor was among the earliest to be constructed in Armenia, and until its destruction, Tekor was the oldest extant domed Church in Armenia (T'oramanyan). The dome was supported by enlarged free-standing pillars. The domeís early date is indicated by the fact that no pendentives or squinches were used to make the transition from the square bay to the circular drum of the cupola as in other Armenian Churches. Instead, four walls extended upward and inclined toward the center. Four slabs were placed diagonally on the corners of the pyramidal form at the base and top to make an octagon on which to rest the cupola. From the exterior the drum appeared to be a massive square crowned by a cornice. Above it was a narrow octagonal zone surmounted by the conical roof. The drum exterior is attributed to reconstruction work undertaken in the 10th century by the Bagratide as indicated in one of the inscriptions. The conical roof was umbrella-shaped.[37]

The west facade contained figural relief sculpture (T'oramanyan and Marr) which appears to be the earliest example of a donor portrait of its type not only in Armenia and the Caucasus but in Christian art in general (Mnatsakanyan, 1971). The cruciform window under the gable with three circular arms and a rectangular base had a human figure with a headdress carved on either side of the opening. Above these two busts were two peacocks biting fruit from a cup at the top. The figures are identified as Sahak Mamikonian and a woman (T'oramanyan), although they were in ruinous condition when they were reported and photographed by T'oramanian and Marr.[37]

There were two decorated portals on the north and one on the west elevation. The west portal had a horseshoe-shaped archivolt supported by two square pillars, each with four columns. Floral motifs on the capitals of the piers are similar to those in other Armenian basilicas (Kasal, 4th century and Ereroyk', 5th century) and in 6th century Syrian Churches (S. Serge of Dar Qita, and Churches at Kimar and Meez). Tekor had large windows with extended arches characteristic of 5th-7th century Armenian Churches. During reconstructions between the 10th and 12th century, many of these were narrowed and splayed in accordance with the style of the period. Red stone was used in earlier parts of the structure and yellow in later sections, offering evidence of changes.[37]

Other indications of renovations include the ribbed, umbrella-like form of the pyramidal roof. The 10th century Churches of Xc'kawnk and Marmasen have somewhat similar coverings. Also, the lining of the pyramidal roof had preserved some tiles typical of roofs earlier than the 7th century.[37]

Subsequent restorations occurred in the course of the 11th to the 14th centuries.[37]

Christina Maranci · 2001 - Medieval Armenian Architecture: Constructions of Race and Nation, pp. 48, 50, 113

- Şeker, Burçin Şenol; Özkaynak, Merve (July 2022). "Seismic Performance Evaluation of Historical Case Study of Armenian Architecture Tekor Church". Civil and Environmental Engineering Reports. 32 (2). Sciendo: 36–52. doi:10.2478/ceer-2022-0018. ISSN 2450-8594. archived PDF

In Armenian architecture, it is accepted as the first domed structure of the Tekor Surp Sergius Church together with the Etchmiadzin Cathedral (Donabédian, 2007).[7]

As in the domed basilica type plan typologies, the middle part of the church is covered with a dome on the inside and a cone on the outside. The church consists of two side naves separated by two columns on the right and left of a main nave (Figure 1a).[7]

There are four independent columns on which the load of the dome is transferred, arches with the width of columns extend to the entrance wall in the west and the apse wall in the east. These columns are connected to the north and south walls with thinner section arches on the horizontal axis. These columns and arches separate the main nave and the side naves. The side naves are covered with vaults extending in the east-west direction. The middle sections of the side naves are covered with barrel vaults in the longitudinal direction up to the bottom of the dome. There are two long rooms on both sides of the apse on the east side of the church. Next to the northern room, there is a semi-circular baptismal font carved into the outer wall (Figure 1b).[7]

There are two doors on the north façade of the church, and one on each on the west and south façades. It is emphasized by a pediment with horseshoe arches on two built-in columns next to the columned doors. The lintel passing over the arches surrounding the doors forms a horizontal dividing facade element. Four columns on both sides of the doors on the north façade and six columns on the west and south façades extend to the horizontal lintel. There are two embrasure windows on the facades of the church (Figure 1c-d).[7]

In addition, the fact that the building materials were removed reveals that it was the result of vandalism as well as the earthquake (URL-1). The church in the 1980s is included in the figure 2c. The current state of the church and the remains can be seen in the figure 2d.[41]

- Romanazzi, H 2009. Domed medieval churches in Armenia

- form and construction. Proceedings of Actas del Sexto Congreso Naional de Historia de la Construccion, Valencia.

http://www.sedhc.es/biblioteca/actas/CNHC6_%20(113).pdf https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Domed-medieval-churches-in-Armenia%3A-form-an-Romanazzi/e30ec99b8fc6fa77adde7aa1bc72efc0647cefee

Among longitudinal churches Surp Sarkis church at Tekor represents a unique solution because it is probably the only survived example of a primitive form of geometric connection between pillars and dome. The almost total loss of the building due to an earthquake in 1912, and, then, to a systematic depredation of the monument during the 20th century

village

[edit]In the early 20th century, the church was located in the Kagizman okrug of the Kars Oblast of the Russian Empire.[15] The village of Tekor (Digor) had a population of over 500 Armenians as of 1913.[15] The Armenian presence came to an permanent end during the Turkish–Armenian War of 1920.[15]

Գյուղ Կարսի մարզի Կաղզվանի օկրուգում, Նախիջևանի տեղամասում, Կաղ- զըվան գք-ից 33 կմ հս-արլ, Տեկորի գետի աջ ափին: 20-րդ դ սկզբներին ուներ 572 (75 տ) հայ բնակիչ: Դպրոցը հիմնադրվել էր 1890 թ:[16]

http://www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru/rnturkey.html 1886 http://www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru/tnaxichevan1886.html село Дигор (Дикор): 360 Armenians: 249 (69,2%), Kurds 88 (24,4%), Turks 23 (6,4%)

По данным «Кавказского календаря» на 1916 год, к 1915 году в городе проживало 1 000 человек, в основном армян[2]. [ «Кавказский календарь на 1916 год». Статистические данные. с. 19] https://www.prlib.ru/item/417321

Տաճար (եկեղեցի, վանք) Կարսի մարզի Կաղզվանի օկրուգում, Նախիջևանի տեղամասում, Տեկոր գ-ում:[16]

Images

[edit]- Charles Texier, 1842 [1]/reproduced in Ghevont Alishan 1881, [2])

-

overall view

-

front view

-

side view

-

cross section

-

floor plan

-

view from south Տեկորի տաճարը, XX դ. սկիզբ, լուսանկարիչ Թորոս Թորամանյան

[32]

https://web.archive.org/web/20231106184357/https://raa-am.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/%D5%8E%D5%A1%D6%80%D5%B1%D6%84-N-2.pdf

Պատկերազարդումը տես 528–529-րդ էջերի միջև՝ ներդիրում, աղյուսակ XVI։[15]

- treasury.am

Խոսրովանույշ թագուհու արձանագրությունը Տեկորի տաճարի պատին, լուսանկարիչ Թորոս Թորամանյան Վիմագրիր արձանագրություն (դրոշմատիպ) XX դ. սկիզբ, լուսանկարիչ Թորոս Թորամանյան Տեկորի տաճարի արևմտյան մուտքի բարավորը լուսանկարիչ Թորոս Թորամանյան, XX դ. սկիզբ լուսանկարիչ Թորոս Թորամանյան, XX դ. սկիզբ Տեկորի տաճարի հյուսիսային ճակատը, Գրքի էջի լուսանկար է Տեկորի տաճարի գծապատկերով, 1941թ., լուսանկարիչ Ե. Ղուկասյան Հեղինակ՝ Ճարտ՝ Ռաֆայել Իսրայելյան

interior https://archive.ph/SyaoN Տեկորի տաճարի արևելյան աբսիդը

raw

[edit][72] pp. 54-55

The church of Tekor (ca 485) probably housed the Martyrium of St Sergius with the appropriate relic, according to its foundation inscription40. = For a summary on the study of this cathedral church with the appropriate bibliography, see Donabédian, L’âge d’or (n. 2) pp. 54–57. For the English translation of the dedicatory inscription, see Timothy Greenwood, “A Corpus of Early Medieval Armenian Inscriptions”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, lviii (2004), pp. 27–91, sp. p. 80. According to Zaroui Pogossian, the dedication of the martyrium of St Sergius in Tekor marked the introduction of the relics and cult of a new saint in the northern regions of Armenia. See Zaroui Pogossian, “Ruling Shirak and Aršarunik‘ at the End of the Fifth Century: Sahak Kamsarakan and a Mathematical Problem of Anania Shirakac‘i as a Historical Source”, Orientalia Christiana Periodica, lxxxvi (2020/1), pp. 19–63, sp. pp. 41–42, 47–48, see pp. 57–63 for the dilemma of Tekor’s inscription.

- Garbis Armen

[73] p. 52

There are a number of trends in the development of forms and features in Armenian architecture of particular interest to practicing designers of churches: the superstructure (dome plus drum) of Armenian churches has been continually increasing in proportion to the main building; that most of this increase is due to the relative growth of the dome, from the very primitive and experimental one of Tekor in 486 ad, the first built in stone, to the enormous, daring tower of St. Tadei vank in the sixteenth century.

p. 62

Fig. 5: The Domed Basilica of Tekor The second basilica after Etchmiadzin to receive a dome and the one to survive the longest - until early this century. It is the veritable link between basilicas and churches in Armenia. The Corinthian capitals of the columns and the arches linking pairs of columns betray a mix- ture of Hellenistic and Iranian influences, in the course of evolution towards the graceful blind arcading of tenth- and eleventh-century Arme- nian churches. The horseshoe arches above entrance doors are the earliest known to have been used in a Christian church.

- Arshak Fetvadjian

- Tekor, Ereuyk

[74] The SixthCentury,@c.-Among my studies I have two watercolours which are faithful portraits of the ruins of the churches of EREROUK and TEKOR. The former,which I visited in 1g06, remains as the drawing shows,but TEKOR, which I drew still earlier, was struck by lightning in 1912, after 1,500 years of existence, during several centuries of which it was abandoned. These two monuments are nearly identical in plan,details and technique, and also in the sculpture of their façades (the interiors are bare). They are examples of acharming archaism, and they are generally supposed to be the works of masters who were apprenticed to Syrianarchitects.

- Yakobson, A. L. (1970). "Взаимоотношения и взаимосвязи армянского и грузинского средневекового зодчества [Relationships and connections between Armenian and Georgian medieval architecture]" (PDF). Sovetskaya arkheologiya (in Russian) (4): 41–53. p.44

Вероятно, к VII в. относится и возведение купола над базиликой V в. в Текоре [Marr, Ereruyskaya, 1968, p.27]

https://www.gov.am/am/building/

Elements of Medieval Armenian architecture and monumental sculpture were used by the author of decorative designs (Tekor, Dvin).

- World Monuments Fund, 2014

https://www.wmf.org/publication/ani-context-workshop https://www.wmf.org/sites/default/files/article/pdfs/Ani%20in%20Context%20Report%20Final.pdf

Ani in Context Workshop. September 28-October 5, 2013, Kars, Turkey. New York, 2014.

Экспедиция работала с 20 августа по 16 сентября 1920 г., возглавлял группу ученых известный археолог Ашхарбек Калантар2 , оставивший дневниковые записи, опубликованные в сборнике его трудов уже в наши дни3 . Экспедиция была осуществлена в то время, когда Карсская область входила в состав Первой Республики Армения4 /// 2 Քալանթար Ա., Հայաստան: Քարե դարից միջնադար: Երկերի ժողովածու, Երևան, 2007, էջ 7-8. 2. Храм V в. в Текоре. Фото А. Казаряна, 2013.

Текор (соврем. Дигор), городок, расположенный в 22 км к юго-западу от Ани. На северной окраине – большой храм, датированный надписью 480-ми гг. Это первый известный нам образец крестовокупольной четырехстолпной церкви в мире.

Состояние во время работы Текорской экспедиции 1920 г.

Подчеркнуто ужасающее состояние памятника, частично обрушившегося на глазах современников Калантара по причине безразличного отношения. Утрачены все своды, включая купол, верхняя зона южной стены. Отмечены опасные трещины в конструкциях. Верхняя часть северной стены испещрена отверстиями от пуль, почему Калантар предполагает, что турецкие солдаты занимались стрельбой по церкви со стороны села. Состояние во время работы экспедиции «Ани в контексте» 2013 г.

Сохранилась лишь бутобетонная сердцевина северной и восточной стен на высоте около пяти метров. Лицевые камни полностью выкорчеваны из стен и унесены. Видны следы нелегальных раскопок1 .

https://doi.org/10.2307/989892 Review: Armenian Architecture: A Documented Photo-Archival Collection on Microfiche for the Study of Armenian Architecture of Transcaucasia and the Near- and Middle-East, from the Medieval Period Onwards by V. L. Parsegian

https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/abs/10.1484/J.AT.1.103111 Early Christian architecture of the Caucasus: problems of typology However, one “domed basilica” is found in the book, though under a different name. This is Tekor, “the crossdomed church with 4 free-standing pillars”, the most ancient Armenian church of this type (ɋat. pp. 311-318). It was built as a regular basilica, and rebuilt into a domed one in the late 5th-early 6th century. P.-L. therefore distinguishes two phases: Tekor-1 and Tekor-2. In the list of basilicas we see Tekor-1 (p. 360) and in the Table – “Tekor”, standing for Tekor-2 (Taf. 209-210). We do not know what basilica Tekor-1 was like, the plan does not exist and the monument has long since been lost.

https://hal.science/hal-04183698/

"Culmination of a late antique legacy? The Golden age of Armenian architecture in the seventh century"

https://jfaup.ut.ac.ir/article_76366_en.html Contextual Analysis of Church Architecture; Centralism: A Characteristic Feature of Eastern Church Architecture

https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jhf/issue/79861/1348131 An Investigation of an Important Armenian Church Architecture in terms of Urban Identity: Digor Khtzkong Monastery

https://ph.pollub.pl/index.php/bia/article/view/3820 Toramanyan finds that some of the early Christian basilicas in Armenia initially consisted only of the prayer hall and the oldest structure (probably rectangular) of the apse [33, p. 131]. According to Sahinyan, Toramanyan came to this conclusion while studying the Tekor Temple [34]. Similar examples of reconstructed temples are the churches of Kasagh, Tekor, Yereruik and Odzun (Fig. 3). In particular, the simple three-nave basilica structure of the Tekor Temple, built in the 4th century, was later supplemented by external porticos, present-day apse with adjoining rooms, portals, the apse of the north facade and the dome [33].

http://ethno.asj-oa.am/318/

https://arar.sci.am/dlibra/publication/116797/edition/106517/content

https://www.persee.fr/doc/rebyz_0766-5598_1985_num_43_1_2179_t1_0305_0000_2 Francesco Gandolfo, Le Basiliche armene. IV-VII secolo [compte-rendu] sem-linkThierry Jean-Michel

Chapitre II. L'église de Tekor, l'actuel Digor (p. 20-27). -- Cet édifice se présentait il y a un demi-siècle comme une croix inscrite à quatre appuis libres de la coupole et galerie périphérique. L'architecte T'oramanyan s'est livré, à son propos, à des spécula- tions historiques ingénieuses pour en faire un temple païen transformé en basilique, à laquelle aurait été adjointe plus tard une coupole. N. Marr et Strzygowski pour leur part l'ont daté de la fin du 5° siècle d'après l'analyse d'une inscription réemployée. Tous ces travaux ont été faits en l'absence de fouilles et ont donné lieu à quelques contestations. Néanmoins l'auteur adopte la théorie de T'oramanyan et la datation de Marr sans discussion, sans tenir compte de l'opinion contraire de M. Hasrat'yan ni de l'existence d'un monument typologiquement très proche, la croix inscrite de Cromi en Géorgie, bien datée du 6° siècle. Si les hypothèses reprises par l'auteur sont plausibles, il ne nous paraît cependant pas très prudent de les tenir pour assurées et s'en servir comme bases de référence.

https://hetq.am/hy/article/90753 Վտանգված եզակի մշակութային կառույց՝ Երերույքի տաճար

archive(d)

[edit]- Stepan Mnatsakanian

- Հայկական վաղ միջնադարյան ճարտարապետության կազմավորման երկու փուլերը

https://web.archive.org/web/20170528005854/http://hpj.asj-oa.am/5001/ https://arar.sci.am/dlibra/publication/191363/edition/173815/content

- Հայկական ճարտարապետության հարցերը Նիկողայոս Մառի աշխատություններում (ծննդյան 120-ամյակի առթիվ)

https://web.archive.org/web/20170526014251/http://hpj.asj-oa.am/4191/ https://arar.sci.am/dlibra/publication/190914/edition/173397/content