User:Vincent60030/sandbox

piccadilly line sandbox

- ...that an experiment to encourage passengers to step on the escalator three at a time was trialed at a Piccadilly line station?

- ...that Buckingham, Heathrow and Harrods are on the Piccadilly line?

- ...that it took the Piccadilly line 31 years to fully replace District line services to Hounslow?

- ...that the Aldwych branch of the Piccadilly line was to be extended to Waterloo for decades, but the branch was closed instead in 1994?

- ...that 200,000 children were evacuated via the Piccadilly line during World War II?

- ...that torpedo sights were produced on the Piccadilly line at Earl's Court station during World War II?

- ...that in October 1965, 960 m of new diversion tracks were laid near Finsbury Park within 13 hours?

https://www.railwaygazette.com/vehicles/doors-ordered-for-london-undergrounds-new-piccadilly-line-trains/57088.article https://www.mylondon.news/news/north-london-news/15-things-youll-only-understand-18709669 https://www.newcivilengineer.com/latest/tfl-boss-calls-for-funding-for-piccadilly-line-upgrades-07-02-2020/ https://www.guardian-series.co.uk/news/18571616.piccadilly-line-upgrade-hold-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/ https://thebrakereport.com/knorr-bremse-wins-order-for-london-underground/ https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8494607/PM-calls-driverless-trains-condition-future-TfL-bailout.html

special services page 32

https://tfl.gov.uk/travel-information/improvements-and-projects/four-lines-modernisation https://www.railjournal.com/signalling/underground-ssl-resignalling-goes-live/ https://www.transport-network.co.uk/New-signals-operational-across-half-of-London-Underground/15762

rolling stock 34-35

https://www.wired.co.uk/article/driverless-tube-trains-tfl-boris-johnson http://www.lurs.org.uk/02%20oct%20PICCADILLY%20TO%20THE%20WEST.pdf http://www.metadyne.co.uk/pdf_files/LTSB_new.pdf https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2005/may/new-blue-and-improved-piccadilly-line https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2006/november/piccadilly-line-centenary https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2014/march/customers-set-for-a-smoother-ride-on-the-metropolitan-and-piccadilly-lines https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2015/september/improving-district-and-piccadilly-line-reliability

rolling stock and service cockfosters extension 75, archi 82,86

https://www.watfordobserver.co.uk/news/17358718.croxley-rickmansworth-station-users-suffer-tfl-setbacks/ https://www.onlondon.co.uk/damien-egan-peter-john-the-government-should-back-the-bakerloo-line-extension/

The Piccadilly line is a London Underground line running from the north to the west of London. It contains two branches, which splits at Acton Town, and serves 53 stations. The line is known for serving Heathrow Airport, and is near popular attractions such as Buckingham Palace. The District and Metropolitan lines share some sections of tracks with the Piccadilly line. Coloured dark blue (officially "Corporate Blue", Pantone 072) on the Tube map, it is the fourth-busiest line on the Underground network with over 210 million passenger journeys in 2011/12.

The first section was opened in 1906, between Finsbury Park and Hammersmith as the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR). The station tunnels and buildings were designed by Leslie Green, featuring ox-blood terracotta facades with semi-circular windows on the first floor. When Underground Electric Railways of London (UERL) bought over the line, it was renamed the Piccadilly line. Subsequent rapid extensions were made to Cockfosters, Hounslow West and Uxbridge were made in the early 1930s, which saw many existing stations on the Uxbridge and Hounslow branches rebuilt with designs by Charles Holden, part of the Adams, Holden & Pearson architectural practice. These were generally rectangular brick bases and large tiled windows, topped with a concrete slab roof. The western extensions took over existing District line services, which were fully withdrawn in 1964.

Stations in central London were rebuilt to cater to higher volumes of passenger traffic. To prepare for World War II, some stations were equipped with shelters and basic amenities; others were equipped with blast walls. When the Victoria line was constructed, some sections of the Piccadilly line had to be rerouted for cross-platform interchange. Its first section was opened in 1968, which helped to relieve congestion on the Piccadilly line. Several plans were made to extend the line to serve Heathrow Airport. The earliest approval was given in 1967, and the Heathrow extension opened in stages between 1975 and 1977. This extension served only Terminals 2 and 3 and the former Terminal 1. The line was extended again twice, to Terminal 4 via a loop in 1986, and to Terminal 5 directly from the main terminal station in 2008.

The Aldwych branch, now closed, was a short spur opened from Holborn in 1907. The branch was lightly used, and was marked for closure several times. There were numerous proposals for an extension to Waterloo, but to no avail. The branch was finally closed in 1994, and is now mainly used for filming purposes.

This 53-station tube line has two depots, at Northfields and Cockfosters, with a group of sidings at several locations. Crossovers are at a number of locations, with some allowing for trains to switch onto different lines. The Piccadilly line once had its electricity generated from Lots Road Power station. It was, however, taken out of use in 2003, leaving the line with supply from the National Grid Network. The 1973 stock serves the tube line, where 78 of these are needed to have a 24 trains per hour (tph) service during peak hours. These are due to be replaced by the New Tube for London (NTfL) trains in the 2020s.

Route

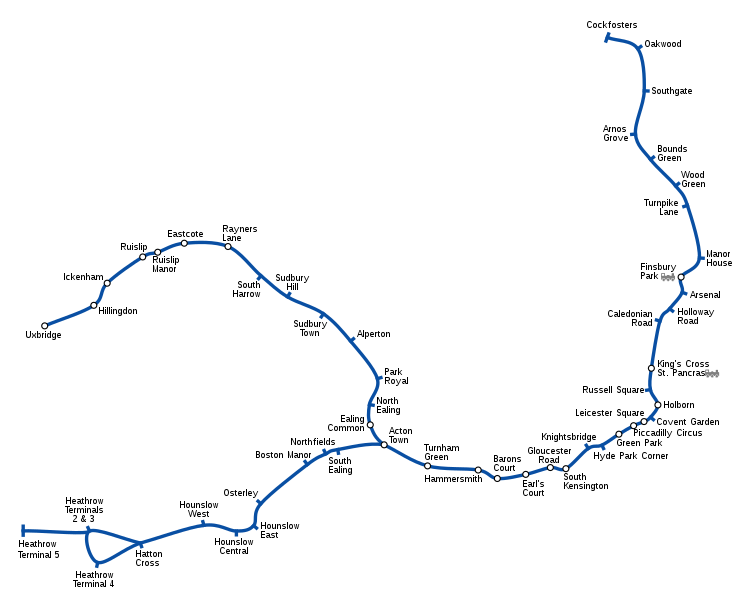

[edit]The Piccadilly line is a 73.97 km (45.96 mi) long North — West line, which consists of two branches splitting at Acton Town, serving 53 stations.[1][2] Cockfosters is a four-platform three-track terminus, and the line runs at-grade to just south of Oakwood. Southgate station is in tunnel, with tunnel portals to the north and south. A viaduct carries the tracks along Arnos Park before arriving at Arnos Grove due to the difference in terrain.[3] The line then descends into twin tube tunnels, passing through Wood Green, Finsbury Park and central London. The lattermost area contains a few stations in close proximity to popular attractions, such as London Transport Museum, Harrods, Buckingham Palace and Piccadilly Circus. The 15.3km tunnel ends east of Barons Court, where the line continues to travel west parallel to the District line to Acton Town. A flying junction, in use since 10 February 1910, separates trains going to the Heathrow branch from the Uxbridge branch.[4][5]

The Heathrow branch remains at surface level until the eastern approach of Hounslow West station, where cut-and-cover tunnels go up to Hatton Cross. Tracks momentarily rise above the River Crane through a viaduct.[6] The line continues in tube tunnels to Heathrow Airport; via the Terminal 4 loop or through to Terminal 5.[7] On the Uxbridge branch, it shares tracks with the District line between Acton Town and south of North Ealing. The line traverses terrain with cuttings and embankments, and continues to Uxbridge, sharing tracks with the Metropolitan line between Rayners Lane and Uxbridge.[8] The distance between Cockfosters and Uxbridge is 31.6 mi (50.9 km).[9]

Map

[edit]

History

[edit]The Piccadilly line began as the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (GNP&BR), one of several railways controlled by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), whose chief director was Charles Tyson Yerkes,[10] although he died before the first section of the line opened.

The GNP&BR was formed from the merger of two earlier, but unbuilt,[11] tube-railway companies taken over in 1901 by Yerkes' consortium: the Great Northern & Strand Railway (GN&SR) and the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway (B&PCR).[12] The GN&SR's and B&PCR's separate routes were linked with an additional section between Piccadilly Circus and Holborn. A section of the District Railway's scheme for a deep-level tube line between South Kensington and Earl's Court was also added in order to complete the route.[note 1] This finalised route, between Finsbury Park and Hammersmith stations, was formally opened on 15 December 1906.[15] On 30 November 1907, the short branch from Holborn to the Strand (later renamed Aldwych) opened; it had been planned as the last section of the GN&SR before the amalgamation with the B&PCR.[16]

Initial ridership growth was low due to the popularity of new electric trams and motor buses. Financial stability was an issue, and as a result the company heavily promoted their railways via a new management team. UERL also agreed with other independent railway companies such as the Central London Railway (CLR) to jointly advertise a combined network known as the Underground.[17][18] On 1 July 1910, the GNP&BR and the other UERL-owned tube railways (the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway and the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway) were merged by private Act of Parliament[19] to become the London Electric Railway Company (LER).[note 2] The Underground railways still suffered financial issues,[21] and to address this, the London Passenger Transport Board was established on 1 July 1933.[22][23]

There were a number of notable station layout changes in the 1910s and 1920s. On 4 October 1911, Earl's Court had new escalators installed connecting the District and Piccadilly lines. They were the first to be rolled out on the Underground.[20][24] On 10 December 1928, a rebuilt Piccadilly Circus station, designed by Charles Holden,[25] was opened. This included a new booking hall relocated below-ground and eleven escalators, replacing the original lifts.[26][note 3]

One of the shafts at Holloway Road station was used as an experiment for spiral escalators, but was abandoned since 1911.[28] An experiment to encourage passengers to step on the escalator three at a time at Manor House station was trialled. It failed due to opposition and potential dangers pointed out by the public.[29]

Extension to Cockfosters

[edit]

While early plans to serve Wood Green (specifically Alexandra Palace) existed since the 1890s as part of the GN&SR,[30][31] this short section to Finsbury Park was later dropped from the GNP&BR proposal in 1902 when the company was bought over.[32][33] In 1902, as part of an agreement for buying over the GN&SR, The Great Northern Railway (GNR) imposed a sanction on Yerkes to abandon the section north of Finsbury Park and they would construct the terminus below ground.[33][34][35][36] Finsbury Park remained as an overcrowded terminus of the line, and was described as "intolerable". Many passengers had to change onto buses, trams, and suburban rail services to complete their journeys up north.[37][note 4] The GNR attempted to address this issue by considering electrification frequently, but to no avail due to shortage of funds. Meanwhile, the LER proposed an extension in 1920 but was overruled by the GNR, which was widely regarded as "unreasonable". In 1923, a petition by the Middlesex Federation of Ratepayers to repeal the 1902 parliamentary act emerged. It was reported that "fierce exchange of arguments" occurred during a parliament session in March 1924 to request for this change.[38][36] Frank Pick, as the new Assistant Managing Director of the Underground, distributed photographs of the congestion at Finsbury Park to the press. All of this pressure finally prompted the government to initiate "The North and North-East London Traffic Inquiry", with initial reports only recommending a one-station extension to Manor House. The London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), being the successor of the GNR, was placed in the position of electrifying its own services or withdrawing its veto to an extension of the Piccadilly line. With again insufficient funds to electrify the railway, the LNER reluctantly gave into the latter decision.[35] An extension was highly likely at this stage, based on a study in October 1925 by the London & Home Counties Traffic Advisory Committee.[39][40]

Pick, together with the Underground board began working on the extension proposal. Much pressure was also received from a few districts such as Tottenham and Harringay, but it was decided that the optimal route would be the midpoint of the GNR and the Hertford Line.[note 5] This was backed by the Committee, and parliamentary approval for the extension was obtained on 4 June 1930, under the London Electric Metropolitan District Central London and City and South London Railway Companies Act, 1930.[41][42][note 6] Funding was obtained from legislation under the Development (Loan Guarantees and Grants) Act instead of the Trade Facilities Act. The extension would pass through Manor House, Wood Green and Southgate, ending at East Barnet (now Oakwood);[44] based on the absence of property development along the line. In November 1929, the projected terminus was later shifted further north to Cockfosters to accommodate a larger depot. Ridership was estimated to be 36 million passengers a year on the extension, costing £4.4 million.[43] Stations were designated at Southgate, Arnos Grove, Bounds Green, Wood Green, Turnpike Lane, and Manor House, in addition to East Barnet. St. Ann′s Road or Harringay Green Lanes was originally part of the scheme, but was dropped to maintain high average speeds in between stations.[note 7] This also compensated for a more expensive provision for construction of a third track between Finsbury Park and Wood Green.[46][42]

Tunnel rings, cabling and concrete were produced in Northern England, while unemployed industrial workers there helped in the construction of the extension. Construction of the extension started quickly, with the boring of the twin tube tunnels between Arnos Grove and Finsbury Park proceeding at the rate of a mile per month. 22 tunnelling shields were used for the tunnels,[47] and tunnel diameters were slightly larger than the old section, at 12ft. Sharp curves were also avoided to promote higher average speeds on the extension. 400 ft (120 m) long platforms were originally planned for each station to fit 8-car trains, but was cut short to 385 ft when built. Some stations were also built with wider platform tunnels to cater to expected high patronage. Connecting buses and trams interchange stations were fitted in with exits which led passengers directly to the bus terminal or tram stop from the subsurface ticket hall. The exits were purposed to improve connections which avoided chaotic passenger flow such as at Finsbury Park. Wood Green was an exception due to engineering difficulties, with the ticket hall at street level instead. Ventilation shafts were provided at Finsbury Park Tennis Courts, Colina Road and Nightingale Road, supplementing the existing fans within the stations. Provisions for future branch lines to Enfield and Tottenham were made at Wood Green and Manor House respectively, both to have reversing sidings. This had since changed, with only a reversing siding built at Wood Green and no provision for the branch line. Arnos Grove was built to have 4 platforms facing 3 tracks for trains to reverse regularly, with seven stabling sidings instead of one reversing siding and two platforms.[48][49][50]

Most of the tunneling works were completed by October 1931, with the Wood Green and Bounds Green station tunnels done by the end of the year.[42] The first phase of the extension to Arnos Grove opened on 19 September 1932, without ceremony. The line was further extended to East Barnet (then renamed Enfield West) on 13 March 1933 and finally to Cockfosters on 31 July 1933, again without ceremonies.[40][51] The total length of the extension was 12.3 km (7.6 mi).[2] Residents were distributed free tickets on first days of each extension. Initial ridership was 25 million at the end of 1933, and sharply increased to 70 million in 1951.[52] Despite having no official openings, the Prince of Wales visited the extension on 14 February 1933.[53][note 8]

Westward extensions

[edit]The Hounslow West (then Hounslow Barracks) extension of the Piccadilly line, together with the Uxbridge extension, aimed to improve services on the District line which at the time were serving both branches from Acton Town (then Mill Hill Park).[55][note 9] The Uxbridge extension followed along existing routes on the District Railway (DR) and Metropolitan Railway (Met). The Ealing & South Harrow Railway (E&SHR) was approved in 1894 and completed in 1899 after approximately a two-year construction period. Insufficient funds from the DR delayed its opening. On the other hand, the Harrow & Uxbridge Railway (H&UR) was proposed in 1896 and authorised a year later.[57] The Met offered to fund the line, with conditions to take over the Rayners Lane to Uxbridge section of the H&UR. Agreement was reached in 1899, with the Met also constructing the connection from South Harrow to Rayners Lane, whilst allowing up to three trains an hour from the DR between South Harrow and Uxbridge.[58] Construction began in 1901, and the Met opened its extension to Uxbridge on 30 March 1904.[57][59] Meanwhile, the DR opened a short spur from Ealing Common to Park Royal on 23 June 1903 to serve the Royal Agricultural Show. Five days later, it was open to South Harrow. Through trains of the DR were eventually extended to Uxbridge on 1 March 1910.[60]

The viaduct from Studland Road (now Studland Street) Junction west of Hammersmith to Turnham Green was quadrupled on 3 November 1911. The London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) used the northern pair of tracks while the District Railway used the southern pair.[61] The LER proposed an extension in November 1912 to Richmond due to available capacity to the west and the fact that passenger interchanges were large at Hammersmith. It would connect with the L&SWR tracks at Turnham Green.[62] It was approved as the London Electric Railway Act, 1913 on 15 August 1913,[63] but the emergence of World War I resulted in no works done on the extension.[64] A Parliamentary report of 1919 recommended through running to Richmond and Ealing.[65] The Richmond extension plan was revived in 1922 by Lord Ashfield, the Underground's chairman. It was decided that the Piccadilly line extension was favourable over the Central London Railway's (CLR, now part of the Central line).[66][note 10] By 1925, the District line was running out of capacity west of Hammersmith, where services were headed to South Harrow, Hounslow Barracks, Richmond and Ealing Broadway. Demand was also low on the South Harrow branch because of infrequent services and competition among other rail lines within near vicinity of each station. This prompted the Piccadilly line extension to be an express service between Hammersmith and Acton Town, with the future Heathrow Airport extension kept in mind. The Piccadilly line would run on the inner pair of tracks, and the District on the outer.[65] Permission was granted to quadruple tracks to Acton Town in 1926 in conjunction with permit renewal for the extension. The Richmond extension never happened, but provisions allocated would allow this option to be revisited later. Extensions would instead be to Hounslow Barracks and South Harrow, taking over DR services to the latter, with an estimated cost of £2.3 million.[69][note 11] In 1930, unsuccessful negotiations were made between LER and the Met to extend Piccadilly line trains to Rayners Lane for passengers to change trains.[71]

In 1929, quadrupling was to extend to Northfields for express trains to terminate here. This work was completed on 18 December 1932. Overall works for the extension began in 1931, approximately a year after permission was granted and funded under the Development (Loan Guarantees and Grants) Act of 1929. The Studland Road Junction area was partially rebuilt, with some of the old viaducts retained to date. The junctions diverging to Richmond were reconfigured at Turnham Green. Reversing facilities were initially designated at the latter, but these were not built.[72] Trial runs of Piccadilly line trains began on 27 June 1932. On 4 July 1932, services were extended to South Harrow, which replaced DR services. Northfields services were introduced on 9 January 1933, and on 19 March, was extended to Hounslow West. On 1 July 1933, the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) was formed, which included the Met, the DR and LER.[22] The board decided that there is sufficient demand to run through trains to Uxbridge due to rapidly developing suburbs along the line. The Uxbridge extension opened on 23 October 1933, but with many trains still reversing at South Harrow. By then, most Piccadilly line trains continued beyond Hammersmith, and District line trains to Hounslow were reduced to off-peak shuttles to Acton Town. An enhanced off-peak Piccadilly line service was introduced on 29 April 1935, cutting off-peak District line services down to the Acton Town — South Acton shuttle.[73] South Harrow short trips proved to be an inconvenience. The solution was to move reversing facilities to Rayners Lane. Rayners Lane received a new reversing siding in 1935, which allowed some peak hour trains to terminate beginning in May 1936. Regular reversals were fully implemented in October 1943.[74] Peak-hour District line trains to Hounslow were fully withdrawn on 9 October 1964.[75]

These eastward and westward extensions feature Modernist architecture at their stations, many of them designed by Charles Holden, who was inspired by examples of Modernist architecture in mainland Europe. This influence can be seen in the bold vertical and horizontal forms, which were combined with the use of traditional materials like brick.[76] Many of these Holden-designed stations are listed buildings.

hounslow branch

-note: hounslow & met railway 1 may 1883 to hounslow town (p=42) (later closed in 2 may 1909), branch to hounslow barracks 21 july 1884 as single track -district taken over in 1903 as a branch p=42 -heston-hounslow 31 march 1886, northfields 16 april 1908 p=46 -new hounslow town replaced, double track to heston-hounslow 24 april 1910, p=46 -10 february 1910 flying junction built passing hounslow tracks p=46 -Studland road (studland street) to turnham green viaduct widened in 3 november 1911 (note: L&SWR used northern pair, district railway used southern pair) p=46,47 -piccadilly part of LER consider extension to richmond due to available capacity and many ppl interchange (p=48) granted on 15 august 1913 competing with CLR p=48 -interrupted by world war i lord ashfield revived the scheme p=49 -1914 approval renewed 1926, quadrupling granted to acton town p=49 -timing issues reaching capacity on district. solution express and slow between acton and hammer. picc inner dist outer with picc chosen as fast to futureproof heathrow note:1925 30 trains in peak, 20 beyond hammersmith, only 1 train south harrow to south kensington, 5 trains to richmond 1930 no space. off peak to northfields and hounslow, south acton to south harrow and uxbridge p=50,51 -1929 quadrupling line to northfields p=52, trains would call only at h, turn, act, norf, 18 december 1932 done, p=58 -barracks double 27 november 1926 p=54 -construction powers granted in 1930, work began in 1931 p=54 -hammersmith area reconstruction and turnham green p=54 -trial runs of picc 27 june 1932 p=57 -picc northfields extension 9 january 1933, 13 march almost all trains go beyond hammersmith, and extension to hounslow west -district service to hounslow withdrawn 29 april 1935 alongside enhanced picc off peak service p=58

uxbridge branch

-1864 bills harrow-alperton area. ealing & south harrow rail ealing broadway to roxeth (harrow hill) approved 1894 p=42-43 -work started 1897, 1899 done but unused -harrow & uxbridge railway 1896 bill, authorised in 1897 -met rail funded the line, construction started in 1901, south harrow to uxbridge and harrow to rayners, act of 1899 -district rail have up to 3tph allowed on the sh to ux section p=44-45 -E&SHR opened 23 june 1903, to serve royal agri show, ealing common to park royal, 28 june south harrow -trains extended to uxbridge 1 march 1910 -demand low on district shuttle -piccadilly would extend to south harrow, leaving the district with sh to ux shuttle p=52 note:oct 1930 proposal of few through districts to sh in rush hrs -4 july 1932 south harrow picc service replaces district trains p=57 -1930, underground intend to send picc trains to rayners lane but cant agree in terms with met rail p=58 -1 july 1933 lptb merge made through picc trains to uxbridge on 23 october 1933, but many still reversed at south harrow -south harrow reverse inconvenient during peak, moving reversing facilities to rayners. rayners received new western reversing siding in 1935 -some peak trains extended to rayners in may 1936, regular reversal fully implemented october 1943

Station reconstruction and modernisation

-hammersmith rebuild works december 1930 p=54 -acton town rebuilt twice p=46 1931 reconstruction -barracks rebuilt 3 platforms 1926 p=54 -p=61, and platform height alteration

Modernisation, World War II and Victoria line

[edit]In conjunction with the new extensions, seven stations were considered to be closed to increase overall line speeds. Down Street closed on 21 May 1932, Brompton Road on 29 July 1934, and York Road on 17 September 1932.[51][77] All three stations were lightly used, with Down Street and Brompton Road replaced by relocated entrances of Hyde Park Corner and Knightsbridge respectively. Notably, Knightbridge's new below ground ticket hall required stairwells from the entrance, one of which took over part of the Barclays Bank branch there. Both of the latter two stations retained their existing platforms, but the access from the surface was reconstructed with their entrances closer to the closed stations. These new entrances feature escalators, which replaced the lifts, improving passenger circulation. The Aldwych branch was deemed unprofitable, and in 1929 an extension to Waterloo which would have costed £750,000 was approved. No progress was made on the extension. Dover Street (now Green Park), Leicester Square and Holborn stations received new sets of escalators, with the latter most having four in a single shaft. These were completed in the early 1930s.[78][79][80] As part of the 1935–40 New Works Programme, Earl's Court was reconstructed largely at street level. At King's Cross St. Pancras, the Piccadilly and Northern lines were finally connected via new escalators, albeit its construction delayed due to financial difficulties.[81] As a result, Russell Square station retained its lifts.[82][note 12]

To prepare for World War II, several stations had blast walls added, others, such as Green Park, Knightsbridge and King's Cross St. Pancras had floodgates installed which resulted in temporary closures. The line was also involved in the evacuation of 200,000 children by transporting them to both ends of the line, then transferred to mainline trains where they continue their journeys to different country distribution hubs. Some underground stations were fitted in with bunk beds, toilets and first aid facilities, and sewage. Being disused, Down Street was converted to an underground bunker.[84] Other stations such as Holborn and Earl's Court had also essential wartime uses. The former had the Aldwych branch platforms as the wartime engineering quarters whilst the branch service was temporarily closed.[85] The latter produced torpedo sights at the transfer concourse between the District and Piccadilly lines.[86]

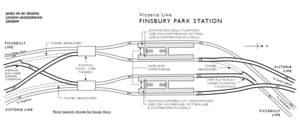

Proposals for a new line, known as "Route C",[87][88] which aimed to relieve congestion of several Underground lines was tabled since 1943.[89] It was eventually named the Victoria line.[87] During the planning stages, a proposal was put forward to add a stop at Manor House. This was later scrapped.[90] Cross-platform interchange was to be provided at a few stations, which included Finsbury Park on the Piccadilly line.[91] This meant that the Piccadilly line had to be realigned there, and the Northern City line platforms, being parallel to the existing Piccadilly line platforms, were to be transferred to the pair of lines. The Northern City line would be redirected to the surface platforms. The westbound Piccadilly line track would be rerouted onto one of these platforms, with the southbound Victoria line using the other. The northbound Victoria line would reuse the old westbound Piccadilly line platform and a part of the old tunnels, with the Piccadilly line diversion tunnels spanning 3,150 ft (960 m).[92]

Construction of the diversion began in October 1964, with the Northern City line having a temporary closure.[93] At the northern junction, step plate junctions were built to divert the existing line when the new tunnels were complete. They were fitted into the original Northern City line tunnels which had a greater tunnel diameter until two running tunnels were able to merge. The old and unused running tunnel was disconnected and blocked off when the junction tunnel was near its completion. This was done carefully as live cabling and tracks were involved. Alteration of temporary points junctions and shifting of signals completed the diversion tunnels. In the south, the Piccadilly would be diverted to descend sharply under the northbound Victoria line tunnel, and then ascending to the original level which had a difference of 5 ft approximately 200 ft (61 m) north of Arsenal station. The old westbound tunnel had to be supported on a trestle for works to be done. The trestle and old tracks were entirely removed once the diversion was ready for switchover. New tracks were laid at a rapid rate which were done in about 13 hours on 3 October 1965.[92] Both lines were connected via junctions south of Finsbury Park for stock movement and engineering trains. At King's Cross St. Pancras and Green Park, the ticket hall was reconstructed to accommodate new traffic on the Victoria line. It was intended for Green Park to have cross-platform interchange, but was deemed impossible due to the lines crossing at right angles. A substation for the Victoria line was installed at one of the old lift shafts there. The Victoria line opened on 1 September 1968 from Walthamstow Central to Highbury & Islington via Finsbury Park, and on 7 March 1969 to Warren Street via King's Cross St. Pancras,[94] providing relief to the Piccadilly line.[95]

During the planning stages of the Victoria line, a proposal was put forward to transfer Manor House station to the new line, and also to build new "direct" tunnels from Finsbury Park to Turnpike Lane station, thereby cutting the journey time in and out of central London. This idea was eventually rejected due to the inconvenience to passengers that would have been caused during rebuilding, as well as the costs of the new tunnels.[96]

Extension to Heathrow Airports

[edit]

To cater to the rapid growth of road traffic to Heathrow Airport, several rail lines were considered to serve the airport. An average increment of 1 million passengers a year between 1953 and 1973, and rising issues with airline coach services from major terminals due to location, traffic congestion, larger aircraft capacity and increasing leisure travel further arose the need for public transport connections. Other than the Piccadilly line extension from Hounslow West,[note 13] a Southern Railway spur (section now transferred to part of South Western Railway) from Feltham was also contemplated. These schemes were brought into parliamentary discussion in November 1966, and were approved with the Royal Assent as the London Transport Act, 1967 and British Railways Act, 1967 respectively on 27 July 1967.[98] Partial government funding was obtained in April 1972 for the 3.5 mi (5.6 km) Piccadilly line extension, and the estimated cost of construction was £12.3 million.[99]

On 27 April 1971, a construction ceremony was launched by Sir Desmond Plummer, leader of the Greater London Council by bulldozing "the first sod". Platforms at Hounslow West had to be relocated below-ground to the north of the existing for the new track alignment. The 1931 ticket hall was retained, with connections to the new platforms. A new cut-and-cover excavation method was used between Hounslow West and Hatton Cross, a new station on the extension. This 2-mile section had a shallow trench dug, with the tunnel walls supported by intersecting concrete piles. The line had to cross River Crane just east of Hatton Cross, therefore it emerges briefly on a bridge, with the two portals having concrete retaining walls. Deep tube tunnels were bore from Hatton Cross to Heathrow Terminals 2 & 3 (then named Heathrow Central). On 19 July 1975, the line was extended to Hatton Cross.[note 14] The Heathrow Central extension was inaugurated by the Queen around noon on 16 December 1977, with revenue services commencing at 3pm.[6]

In the 1970s, planning was already underway for a fourth terminal for the airport, and its location was to be to the southeast of the existing terminals. As the Piccadilly line's route to the existing terminals was out of place, a loop track was adopted as the best method to serve the new terminal. The westbound track between Hatton Cross and Heathrow Central would be retained for emergency services. Permissions for constructing for the loop was approved and received Royal Assent under the London Transport Act 1981 on 30 October 1981.[101] On 19 July 1982, the original location of the station and track alignment were altered to compensate for the British Airport Authority (BAA) to finish the fourth terminal building which was behind schedule. Construction of the 2.5 mi (4.0 km) extension began on 9 February 1983, with an estimated cost of £24.6 million. The loop was built rapidly, with tunneling completed in 17 months. It was expected that the extension would open with the new terminal. However, the terminal opening was delayed, with the loop service completed and commissioned on 4 November 1985. The terminal and station were finally opened a few months later on 1 April 1986, by the Prince and Princess of Wales. Regular traffic began 12 days later where trains serve Terminal 4 via a one-way loop, and then Terminals 1,2,3.[102] The station only has a single platform, and is the only one with this configuration on the Piccadilly line.[50]

The new Terminal 5 would require another extension, funded by BAA. However, its alignment caused some controversy. It was reported that London Underground was unhappy of its location on the old Perry Oaks sludge which was originally intended for Terminal 4. It is now impossible for all 3 terminals to be served on the same route, and the final solution was to have twin tunnels serving Terminal 5 from Terminals 1,2,3. From 7 January 2005 until 17 September 2006, the loop via Terminal 4 was closed to allow this connection to be built. Terminals 1,2,3 became a temporary terminus; shuttle buses served Terminal 4 from the Hatton Cross bus station.[103] Part of the junction between the through and loop tracks had to be rebuilt. The terminal 5 project team had to shut down two aircraft stands from Terminal 3 so that an access shaft could be constructed. The new junction was then built into a concrete box which connected all four underground tunnels.[104] The station and terminal were opened on 27 March 2008, which made Piccadilly line services split into two main services; one via the Terminal 4 loop, another direct to Terminal 5.[105][106]

Notable incidents and events, Aldwych branch closure

[edit]Although the Piccadilly Circus to City of London branch proposal of 1905 was never revisited after its withdrawal, the early plan to extend the branch south to Waterloo was revived a number of times during the station's life. The extension was considered in 1919 and 1948, but no progress towards constructing the link was made.[85]

In the years after the Second World War, a series of preliminary plans for relieving congestion on the London Underground had considered various east-west routes through the Aldwych area, although other priorities meant that these were never proceeded with. In March 1965, a British Rail and London Transport joint planning committee published "A Railway Plan for London", which proposed a new tube railway, the Fleet line (later renamed the Jubilee line), to join the Bakerloo line at Baker Street then run via Aldwych and into the City of London before heading into south-east London. An interchange was proposed at Aldwych and a second recommendation of the report was the revival of the link from Aldwych to Waterloo.[107][108] London Transport had already sought parliamentary approval to construct tunnels from Aldwych to Waterloo in November 1964,[109] and in August 1965, parliamentary powers were granted. Detailed planning took place, although public spending cuts led to postponement of the scheme in 1967 before tenders were invited.[110] By 1979, the cost was estimated as £325 million, a six-fold increase from the £51 million estimated in 1970.[111] A further review of alternatives for the Jubilee line was carried out in 1980, which led to a change of priorities and the postponement of any further effort on the line.[112] When the extension was eventually constructed in the late 1990s it took a different route, south of the River Thames via Westminster, Waterloo and London Bridge to provide a rapid link to Canary Wharf, leaving the tunnels between Green Park and Aldwych redundant.[113]

With the Aldwych branch receiving no extensions, it remained a lightly used shuttle service from Holborn. The branch was considered for closure numerous times, but it survived.[114] Saturday services were fully withdrawn on 5 August 1962.[115] Maintenance costs of the station and aged lifts were high at over £3 million, which failed to meet safety standards at the time. In August 1993, a public inquiry was held for closure of the short branch line. On 30 September 1994, the branch was closed to traffic.[note 15] The disused station is now used for commercial filming and a training facility.[116]

On 18 November 1987, a massive broke out at King's Cross St. Pancras, where the incident was near the Northern / Piccadilly line escalators which killed 31 people.[117][118] As a result, wooden escalators were replaced at all Underground stations.[119][120][note 16] The Piccadilly line platforms remained opened, but with the escalators to the ticket hall closed for repairs. Access was temporarily via the Victoria line or Midland City platforms. New escalators were fully installed on 27 February 1989.[124]

On 7 July 2005, a Piccadilly line train was attacked by suicide bomber Germaine Lindsay.[125] The blast occurred at 08:50 BST while the train was between King's Cross St. Pancras and Russell Square. It was part of a co-ordinated Islamist terrorist attack on London's transport network, and was synchronised with three other attacks: two on the Circle line and one on a bus at Tavistock Square. The Piccadilly line bomb resulted in the largest number of fatalities, with 26 people reported killed. Owing to it being a deep-level line, evacuation of station users and access for the emergency services proved difficult.[126] Shuttle services had to be introduced between Hyde Park Corner and Heathrow loop, between Acton Town and Rayners Lane, and between Arnos Grove and Cockfosters. Full service was restored on 4 August, four weeks after the bomb.[117][106]

On 15 December 2006, a birthday card was revealed by Tim O'Toole, then London Underground Managing Director during a 100-year celebration of the Piccadilly line at Leicester Square station.[127]

Architecture

[edit]Most of the deep level stations opened in the first phase between Finsbury Park and Hammersmith were built to a design by Leslie Green.[128] This consisted of two-storey steel-framed buildings faced with dark oxblood red glazed terracotta blocks, with wide semi-circular windows on the upper floor. Earl's Court station was built with a red brick building by Harry Ford,[129] with semicircular windows on the second level and embedded names of the railways which operated through the station. This replaced a wooden hut building[130][131] and is listed as Grade II.[132]

Extensions of the Piccadilly line towards the west and north in the 1930s had new stations designed by the Adams, Holden & Pearson architectural practice of the Underground, with Charles Holden the main designer. These designs were inspired by modern architecture seen in a 1930 trip to a number of European Countries.[133][134]

Several stations on the western extension, which were opened by the District Railway, were to be reconstructed. The new designs were to use brick, concrete and glass, composing of simple geometrical shapes, such as cylinders and rectangles. The first prototype station was Sudbury Town station, which had the main structure a brick cuboid box, with tall windows above the entrances, then topped by a concrete slab roof. This was then replicated across many other station prototypes.[135] Some stations were designed by delegated architects of Holden due to workload, such as Stanley Heaps and Felix Lander.[136][137] Other stations had their original stations kept. South Ealing was an anomaly, where a temporary wooden station ticket hall was constructed when the line was quadrupled. A modern station was provided in the 1980s.[138][139][note 17] The northern extension stations also were part of the design schemes undertaken by this practice. Southgate was distinctively different, with a round base followed by a cylindrical panel of clerestory windows, topped by an illuminative feature with a bronze ball.[140] The ticket halls had passimeters, which functioned as free-standing ticket booths. Most of them went out of use post World War II, while some have been converted for retail use.[141] Many of these Holden-designed stations are listed buildings. Oakwood, Southgate, and Arnos Grove were a few of the early receivers of listed status, in 1971.[29][142][143][144]

Stations in Central London were modernised with a variety of changes. Green Park received a new shelter at the southern entrance; Piccadilly Circus had its ticket hall moved below street level. Both of these features were designed by Holden,[145] with the latter station ticket hall added with artwork commemorating Frank Pick in 2016.[146][147] Green Park was built with a new entrance at a corner of Devonshire House, which has Portland Stone clad steel frames.[148] It features Graeco Roman details, and is Grade II listed.[149]

Stations on the northern extension had particular biscuit (square) tiles on platform walls, with different freize colours at each station. A few stations like Southgate and Bounds Green have art deco uplighters on escalators and the lower landings.[143][150] Floodlighting was used considerably to provide a spacious ambience. Ventilation ducts were by the platforms walls, sealed with bronze art deco style grilles.[151] Oakwood was built with a concrete canopy with rooflights and cylindrical light fittings, designed by Heaps.[144] Older stations such as Caledonian Road have platform tilings with arcs clad along the tube platforms, with each arc spaced 11–12 ft (3.4–3.7 m) apart. On the platform end, geometrical tiles were squeezed into a defined horizontal region; varying among stations. Arc lighting was complemented with incandescent lamps to illuminate the platforms. Signage decorations present spelt out the station name, with their font size 15 in (38 cm) high.[152][153] These were also designed by Green.[128][note 18]

LIFTS ESCALATORS BLAH horne p=25 platforms p=61 escalator faster p=82

DEPOT CROSSOVERS ROLLING STOCK ETC horne p=26,27,28,29,34,35,36,37,38,57,58,59,74,75,90,93,98,99,101,107,108,109,110,111,122,123,126,127,128,135,136,138 rolling stock also mention met line on shared section and district line four track section

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

tubemapwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Calculations were based on the mileage given in the reference. Feather, Clive (8 May 2020). "Piccadilly Line – Layout". Clive's Underground Line Guides. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 46.

- ^ "Piccadilly line facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 138.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 99.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 6, 8.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 10.

- ^ "No. 26797". The London Gazette. 22 November 1896. pp. 6764–6767.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, p. 181.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 9, 13, 19.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 282–283.

- ^ "No. 28311". The London Gazette. 23 November 1909. pp. 8816–8818.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, pp. 259–262.

- ^ a b Wolmar 2004, p. 266.

- ^ "No. 33668". The London Gazette. 9 December 1930. pp. 7905–7907.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, p. 182.

- ^ Historic England. "Piccadilly Circus Underground Station Booking Hall Concourse and Bronzework to Pavement Subway Entrances (1226877)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 39.

- ^ Lee 1966, p. 23.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 23.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 82.

- ^ "No. 27025". The London Gazette. 22 November 1898. pp. 7040–7043.

- ^ "No. 27105". The London Gazette. 4 August 1899. pp. 4833–4834.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 131.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 138.

- ^ a b Martin 2012, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b c Dean, Deadre. "Part One". The Piccadilly Line Extension. Hornsey Historical Society. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 91.

- ^ "London and North Eastern Railway Bill (By Order)". Hansard Parliament UK. 15 March 1924. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 65.

- ^ a b Wolmar 2005, pp. 227–231.

- ^ "No. 33613". The London Gazette. 6 June 1930. p. 3561.

- ^ a b c Dean, Deadre. "Part Two". The Piccadilly Line Extension. Hornsey Historical Society. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 70.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Martin 2012, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 69, 74–75, 86.

- ^ "Arnos Grove tube station". Google Maps. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b Jarrier, Franklin. "Greater London Transport Tracks Map" (PDF) (Map). CartoMetro London Edition. 3.9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Rose 1999.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 100.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 92.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 42, 46.

- ^ a b Simpson 2003, p. 97.

- ^ Horne 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 46–47.

- ^ "No. 28665". The London Gazette. 22 November 1912. pp. 8798–8801.

- ^ "No. 28747". The London Gazette. 19 August 1913. pp. 5929–5931.

- ^ Horne 2006, p. 56.

- ^ a b Barker & Robbins 1974, p. 252.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Horne 2006, p. 55.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 50–51, 66.

- ^ Horne 2006, pp. 52, 56.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Horne 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 54, 57–58.

- ^ Horne 2006, p. 88.

- ^ "Underground Journeys: Changing the face of London Underground". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Lee 1966, p. 22.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2016, p. 212.

- ^ "Underground Journeys: Leicester Square". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Architectural Plan and Elevation". London Passenger Transport Board. 1933. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 131.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 92–96.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 96.

- ^ Connor 2006, p. 33.

- ^ a b Connor 2001, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 103–106.

- ^ a b Day & Reed 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Klapper 1976, p. 123.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Gelder, Sam (1 September 2018). "Victoria line turns 50: How North London artery brought about a Renaissance for the London Underground". Islington Gazette. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ HMSO 1959, p. 13.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 113.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 163.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 166.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 114.

- ^ Gelder, Sam (1 September 2018). "Victoria line turns 50: How North London artery brought about a Renaissance for the London Underground". Islington Gazette. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 117–118.

- ^ "No. 44377". The London Gazette. 1 August 1967. p. 8450.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 115–120.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 121.

- ^ "No. 48785". The London Gazette. 5 November 1981. p. 14033.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 137–138.

- ^ "Tube One Step Closer for Heathrow Terminal 5" (Press release). Transport for London. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "First Piccadilly Line Passengers Travel to Heathrow Terminal 5" (Press release). Transport for London. 27 March 2008. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ a b Feather, Clive (8 May 2020). "Piccadilly Line". Clive's Underground Line Guides. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Horne 2000, pp. 31–33.

- ^ British Railways Board/London Transport Board (March 1965). A Railway Plan for London (PDF). p. 23.

- ^ "Parliamentary Notices". The Times (56185): 2. 3 December 1964. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012.

- ^ Connor 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Horne 2000, pp. 35 & 52.

- ^ Horne 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Horne 2000, p. 57.

- ^ Connor 2001, pp. 98–, 99.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 134.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 132.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Paul Channon (12 April 1989). "King's Cross Fire (Fennell Report)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 915–917. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Sir Desmond Fennell". The Daily Telegraph. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Mann, Sebastian (11 March 2014). "Tube's only wooden escalator to carry last passengers". London 24. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Fact 121 in the reference. Attwooll, Jolyon (9 January 2017). "London Underground: 150 Fascinating Tube Facts". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Incline lift at Greenford Tube Station is UK First" (Press release). Transport for London. 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 259, 262.

- ^ "Image of Bombers' Deadly Journey". BBC News. 17 July 2005. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ North, Rachel (15 July 2005). "Coming together as a city". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 140.

- ^ a b Wolmar 2005, p. 175.

- ^ Wallinger et al. 2014, p. 155.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Martin 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Historic England. "Earl's Court Station (1358162)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 61.

- ^ "Underground Journeys: Changing the face of London Underground". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Cherry & Pevsner 1991, p. 140.

- ^ Powers 2007.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Horne 2007, p. 55.

- ^ Wallinger et al. 2014, p. 287.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 82, 131.

- ^ Historic England. "Arnos Grove Underground Station (1358981)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Southgate Underground Station (1188692)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Oakwood Underground Station (1078930)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Karol 2007, pp. 481–484.

- ^ Magazine, Wallpaper* (7 November 2016). "Train of thought: artists Langlands & Bell celebrate Frank Pick's design philosophy". Wallpaper*. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Beauty < Immortality". Art on the Underground. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Connor 2006, p. 106.

- ^ Historic England. "Devonshire House (1226746)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Bounds Green Underground Station (Including No. 38) (1393641)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ Horne 2007, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b Horne 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Historic England. "Caledonian Road Underground Station (1401086)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).