User:Umartailor/sandbox

On My First Sonne

[edit]On My First Sonne is a poem by Ben Jonson which was written in 1603 and published in 1616 after the death of his first son Benjamin at the age of seven. The poem, a reflection of a father's pain in his young son's death, is rendered more acutely moving when compared with Jonson's other, usually more cynical or mocking, poetry.

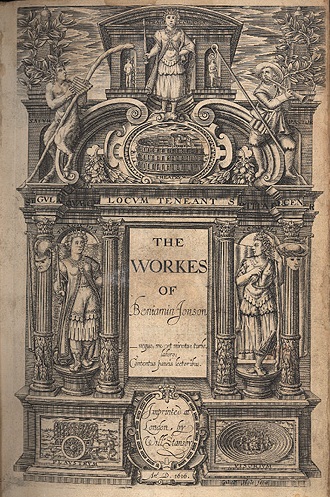

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson

[edit]Ben Jonson(c. 11 June 1572 – 6 August 1637) was an English playwright, poet, actor, and literary critic of the 17th century, whose artistry exerted a lasting impact upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours.

Jonson was a classically educated, well-read and cultured man of the English Renaissance with an appetite for controversy (personal and political, artistic and intellectual) whose cultural influence was of unparalleled breadth upon the playwrights and the poets of the Jacobean era (1603–1625) and of the Caroline era (1625–1642).

Summary

[edit]Ben Jonson wrote this elegy after the death in 1603 of his eldest son, Benjamin, aged seven. The poet addresses the boy, bidding him farewell, and then seeks some meaning for his loss. Jonson blames himself, rhetorically at least, arguing that he hoped too much for his son, who was only on loan to him. Now that the seven years are up, the boy has had to be returned. The poem is a moving exploration of a father's feelings on the loss of his son, made all the more poignant by the difference between its affectionate, resigned tone and Jonson's usually satirical and biting comic voice.

Jonson tries to argue that this is only fair and his presumptuous plans for the boy's future were the cause of his present sense of loss. He then questions his own grief: why lament the enviable state of death when the child has escaped suffering and the misery of ageing? He cannot answer this question, simply saying "Rest in soft peace" and asking that the child, or perhaps the grave, record that his son was Jonson's "best piece of poetry," the creation of which he was most proud. He concludes by vowing that from now on he will be more careful with those he loves; he will be wary of liking and so needing them too much.

Analysis

[edit]Ben Johnson’s ‘On My First Son’ (1616) is an emotive elegy in memory of the speaker’s son, though the title of the poem gives no such indication. The vagueness of it creates a sense of narrative enigma, encouraging the reader to continue reading. In fact, not even the gender of the speaker is clear until the writer acknowledges himself as the persona towards the end of the poem. Nevertheless, as expected, Johnson sustains a melancholic tone throughout poem while exploring the idea of death, family and religion.

The elegy is structured in the expected manner; the lamentation of the loss is followed by the tribute to the deceased, before it ends with a sense of solace and comfort.

Form and structure

[edit]The poem is addressed to his son, but is really a meditation on his own thoughts. It is an elegy, or poem expressing sorrow about the death of loved one.

On My First Son is written in heroic couplets: this means it is made up of rhyming couplets, with each line in iambic pentameter. Six pairs of couplets complete the poem. It is interesting to note that despite the strict adherence to the regular metre the poem still conveys strong emotion.[1]

The poem largely retains a constant form of metre, iambic pentameter. However, there is an abrupt change to iambic hexameter in line 3, ‘Seven years thou wert lent to me, and I thee pay’; it is the only line that explicitly mentions the death[2]. The sudden change draws the reader’s attention to this. The iambic form of the Alexandrine also stresses certain words, particularly ‘lent’, ‘pay’, ‘I’ and ‘me’. The former two emphasise the extended metaphor of his son being a loan from God, which he must pay back with the death. The latter two stresses on the first person pronouns suggests he is seeking the sympathy of the reader. Like the constant rhythm, there is also continuous rhyme in the poem. The poem is written in rhyming couplets. This can be seen as a metaphor in itself, with the couplets reflecting the father-son relationship.

Sonnet

[edit]It is possible that the spelling of 'son' as 'Sonne' is meant to allude to the sonnet form, with which it shares some features. A few other so-called epigrams share this quality.

Language and Imagery

[edit]As might be expected in an elegy, Jonson uses religious language and images to explore his thoughts on the death of his son.

Imagery

[edit]Jonson creates an extended metaphor of his son having been "lent" to him by God, so that he has to "pay" him back on the named day. The image is a powerful one that suggests that while Jonson is grief-stricken he acknowledges that having had "seven years" with his son was a gift from God. The day he died was "the just day", and he also mentions "fate". This reflects the Elizabethan belief in fate. His metaphorical sin was "too much hope of" his son; that is, that he loved him too much, which is an image that is picked up in the final couplet. His grief is also exaggerated in the hyperbolic statement "oh, could I lose all father now!"; he would rather lose the opportunity of fatherhood than suffer the potential grief it brings.

Death is presented as a state that man "should envy" because there you are safe from the misery of the world. In contrast to life, death is described as being "soft peace".[3]

The speaker’s anguish is evident in the hyperbolic statements he makes. In line 5 he claims he ‘could lose all father now’, indicating he is prepared to extinguish his parental feelings. The hyperbole is also apparent in his description of the ‘world’s and flesh’s rage’. The personification of the world’s and humanity’s evils (‘rage’) highlights his belief in the supernatural, suggesting he believes his son is now in a better place after death; heaven. ‘Flesh’s rage’ could also be interpreted as a reference to the vulnerabilities of the human body, with illness and disease being rife at the time of the poem’s publication.

The speaker doesn’t resist in praising the deceased son, describing him as the ‘child of my right hand’ in the first line. The imagery created by this indicates the child was a decent individual, with the word ‘right’ in particular have connotations of positivity. It may also be a literal translation of the boy’s name, Benjamin, in Hebrew[4]. Similarly, the speaker metaphorically describes him as his ‘best piece of poetry’, elevating him to a state of art and demonstrating his near-perfectness. It gives a sense of the relationship between them, and the amount of value that Jonson placed on him.

Sound

[edit]The assonance on the sound ‘o’ emphasises the grief that the poet feels, particularly in lines such as "oh, could I lose all father now!".[3]

Notes

[edit]- ^ BBC GCSE Bitesize Form and Structure: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/english_literature/poetry_wjec/relationships/onmyfirstson/revision/3/

- ^ Shmoop Analysis: Form and Meter: http://www.shmoop.com/on-my-first-son/rhyme-form-meter.html

- ^ a b BBC GCSE Bitesize Language and Imagery: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/english_literature/poetry_wjec/relationships/onmyfirstson/revision/4/

- ^ Ben Johnson, ‘On My First Son’, in The Norton Anthology of Poetry, Ed. By Margaret Ferguson, Mary Jo Salter, Jon Stallworthy (New York: Norton, 2005) p.323.