User:Travel Doc James/sandbox

Transmission

[edit]

The spread of Ebola between people occurs only by direct contact with the blood or body fluids of a person after symptoms have developed.[1][2] Body fluids that may contain ebolaviruses include saliva, mucus, vomit, feces, sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, and semen.[3] Entry points include the nose, mouth, eyes, or open wounds, cuts and abrasions.[3] Contact with objects contaminated by the virus, particularly needles and syringes may also transmit the infection.[4] The virus is able to survive on objects for a few hours in a dried state and can survive for a few days within body fluids.[3] Ebola virus may be able to persist in the semen of survivors for up to seven weeks after recovery, which could give rise to infections via sexual intercourse.[1] Otherwise, people who have recovered are not infectious.[4] The potential for widespread infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing correct medical isolation procedures is considered low.[5] Usually when someone has symptoms, they are sufficiently unwell that they are unable to travel without assistance.[6]

Handling infected dead bodies is a risk, including embalming.[5] Because dead bodies are still infectious, traditional burial rituals may spread the disease. Nearly two thirds of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals.[7][8]

Healthcare workers treating those who are infected are at greatest risk of disease.[4] This occurs when they do not wear appropriate protective clothing such as masks, gowns, gloves and eye protection.[4] This is particularly common in parts of Africa where the health systems function poorly and where the disease mostly occurs.[9] Hospital-acquired transmission has also occurred in African countries due to the reuse of needles.[10][11] Some healthcare centers caring for people with the disease do not have running water.[12] In the United States, spread has occurred due to inadequate isolation.[13]

Airborne transmission has not been documented during EVD outbreaks.[2] Transmission among rhesus monkeys via breathable 0.8–1.2 μm aerosolized droplets has been demonstrated in the laboratory.[14] That airborne transmission does not appear to occur in humans may be due to there not being high enough levels of the virus in the lungs.[15] Spread by water or food other than bushmeat has also not been observed,[4] nor has spread by mosquitos or other insects.[4]

Initial case

[edit]

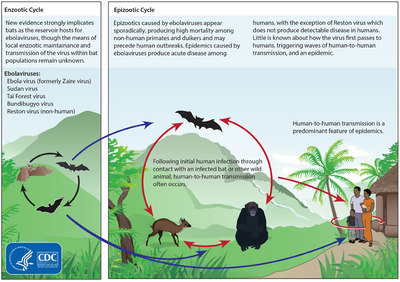

While it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to human, it is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat.[4] Wild animals other than bats capable of being infected include: a number of monkey, chimpanzees, gorillas, baboons and duikers.[17] In Africa wild animals, including fruit bats are hunted to eat, being known as bushmeat.[18][19]

Animals may become infected when they eat fruit already partially eaten by bats carrying the virus.[20] Fruit production, animal behavior, and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.[20]

It does appear that both domestic dog and pigs can also be infected with ebola viruses.[21] Dogs when the carry the virus do not appear to develop symptoms, while pigs appear to be able to transmit the virus to at least some primates.[21]

Reservoir

[edit]The natural reservoir for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate.[22] Three types of fruit bats (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti, and Myonycteris torquata) have been found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick.[20][23] Whether or not other animals are involved in its spread is not known as of 2013.[21] Plants, arthropods, and birds have also been considered as possible reservoirs as well.[1]

Bats were known to reside in the cotton factory in which the first cases of the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were observed, and they have also been implicated in Marburg virus infections in 1975 and 1980.[24] Of 24 plant species and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with EBOV, only bats became infected.[25] The bats displayed no clinical signs and is evidence that these bats are a reservoir species of the virus. In a 2002–2003 survey of 1,030 animals including 679 bats from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo, 13 fruit bats were found to contain EBOV RNA fragments.[26] Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, thus identifying potential virus hosts and signs of the filoviruses in Asia.[27]

Between 1976 and 1998, in 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from outbreak regions, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (Mus setulosus and Praomys) and one shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic.[24][28] Further efforts; however, have not confirmed rodents as a reservoir.[29] Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003, which later became the source of human infections. However, the high lethality from infection in these species makes them unlikely as a natural reservoir.[24]

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

WHO2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "2014 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa". WHO. 21 April 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Q&A on Transmission, Ebola". CDC. September 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Transmission". CDC. October 17, 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ a b "CDC Telebriefing on Ebola outbreak in West Africa". CDC. 28 July 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Air travel is low-risk for Ebola transmission". WHO. 14 August 2014.

- ^ Chan M (2014). "Ebola virus disease in West Africa—no early end to the outbreak". N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (13): 1183–5. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1409859. PMID 25140856.

- ^ "Sierra Leone: a traditional healer and a funeral". World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Tiaji Salaam-Blyther (26 August 2014). "The 2014 Ebola Outbreak: International and U.S. Responses" (pdf). Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Lashley, Felissa R.; Durham, Jerry D., eds. (2007). Emerging infectious diseases trends and issues (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 141. ISBN 9780826103505.

- ^ Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious disease (9th ed.). London, New York: Elsevier. 2013. pp. 170–172. OCLC 822525408.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "Questions and Answers on Ebola | Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever | CDC". CDC.

- ^ "Ebola in Texas: Second Health Care Worker Tests Positive". October 15, 2014.

- ^ Johnson E, Jaax N, White J, Jahrling P (August 1995). "Lethal experimental infections of rhesus monkeys by aerosolized Ebola virus". International journal of experimental pathology. 76 (4): 227–236. ISSN 0959-9673. PMC 1997182. PMID 7547435.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Irving WL (Aug 1995). "Ebola virus transmission". International journal of experimental pathology. 76 (4): 225–6. PMID 7547434.

- ^ Williams E. "African monkey meat that could be behind the next HIV". Health News - Health & Families. The Independent.

25 people in Bakaklion, Cameroon killed due to eating of ape

- ^ "EBOLAVIRUS". http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/. 2014-08-22. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Risk of Exposure". CDC. October 12, 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "FAO warns of fruit bat risk in West African Ebola epidemic". fao.org. 21 July 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Gonzalez JP, Pourrut X, Leroy E (2007). "Wildlife and Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: The Biology, Circumstances and Consequences of Cross-Species Transmission". Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Ebolavirus and other filoviruses. 315: 363–387. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_15. ISBN 978-3-540-70961-9. PMID 17848072.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Weingartl, HM; Nfon, C; Kobinger, G (2013). "Review of Ebola virus infections in domestic animals". Developments in biologicals. 135: 211–8. PMID 23689899.

- ^ "Questions and Answers about Ebola and Pets". CDC. 11 December 2005.

- ^ Pourrut X, Délicat A, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Gonzalez JP, Leroy EM (2007). "Spatial and temporal patterns of Zaire ebolavirus antibody prevalence in the possible reservoir bat species". The Journal of infectious diseases. Suppl 2 (s2): S176–S183. doi:10.1086/520541. PMID 17940947.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Pourrut X, Kumulungui B, Wittmann T, Moussavou G, Délicat A, Yaba P, Nkoghe D, Gonzalez JP, Leroy EM (2005). "The natural history of Ebola virus in Africa". Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 7 (7–8): 1005–1014. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.04.006. PMID 16002313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swanepoel R, Leman PA, Burt FJ, Zachariades NA, Braack LE, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Zaki SR, Peters CJ (Oct 1996). "Experimental inoculation of plants and animals with Ebola virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2 (4): 321–325. doi:10.3201/eid0204.960407. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2639914. PMID 8969248.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Délicat A, Paweska JT, Gonzalez JP, Swanepoel R (2005). "Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus". Nature. 438 (7068): 575–576. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..575L. doi:10.1038/438575a. PMID 16319873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olival KJ, Islam A, Yu M, Anthony SJ, Epstein JH, Khan SA, Khan SU, Crameri G, Wang LF, Lipkin WI, Luby SP, Daszak P (2013). "Ebola virus antibodies in fruit bats, bangladesh". Emerging Infect. Dis. 19 (2): 270–3. doi:10.3201/eid1902.120524. PMC 3559038. PMID 23343532.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morvan JM, Deubel V, Gounon P, Nakouné E, Barrière P, Murri S, Perpète O, Selekon B, Coudrier D, Gautier-Hion A, Colyn M, Volehkov V (1999). "Identification of Ebola virus sequences present as RNA or DNA in organs of terrestrial small mammals of the Central African Republic". Microbes and Infection. 1 (14): 1193–1201. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(99)00242-7. PMID 10580275.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Groseth, A; Feldmann, H; Strong, JE (2007 Sep). "The ecology of Ebola virus". Trends in microbiology. 15 (9): 408–16. PMID 17698361.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)