User:TentingZones1/Featured picture

Picture of the day, were is all stuff in the current day, while of some which is are prominent. such as landscapes.

At its creation, the commune of Lomé was wedged between the lagoon to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the south, the village of Bè to the east and the border of Aflao to the west.

Today, it has experienced a vertiginous extension, and is bounded by the Togolese Insurance Group (GTA) to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the south, the oil refinery to the east, and the Togo-Ghana border to the west. The agglomeration spreads over an area of 333 sq.km. including 30 sq.km. in the lagoon area.

The services of the municipality of Lomé go far beyond the limits of the gulf and the municipality to the north and east of the city.

Distance between Lomé and the rest of the country's cities

Lomé/Tsévié : 35 km

Lomé/Aného : 45 km

Lomé/Tabligbo : 90 km

Lomé/Notsé : 100 km

Lomé/Kpalimé : 121 km

Lomé/Atakpamé : 167 km

Lomé/Blitta : 273 km

Lomé/Sokodé : 355 km

Lomé/Bafilo : 404 km

Lomé/Bassar : 412 km

Lomé/Kara : 428 km

Lomé/Kandé 503 km

Lomé/Mango : 592 km

Lomé/Dapaong : 662 km

On this day

[edit]September 19: International Talk Like a Pirate Day

- 1692 – Salem witch trials: Giles Corey was crushed to death for refusing to enter a plea to charges of witchcraft, reportedly asking the sheriff for "more weight" during his execution.

- 1846 – Near La Salette-Fallavaux in southeastern France, shepherd children Mélanie Calvat and Maximin Giraud reported a Marian apparition, now known as Our Lady of La Salette (statue pictured).

- 1940 – World War II: Polish resistance leader Witold Pilecki allowed himself to be captured by German forces and sent to Auschwitz to gather intelligence.

- 1970 – The first Glastonbury Festival was held at Michael Eavis's farm in Glastonbury, England.

- 1995 – Industrial Society and Its Future, the manifesto of American domestic terrorist Ted Kaczynski, was published in The Washington Post almost three months after it was submitted.

- Theodore of Tarsus (d. 690)

- Paterson Clarence Hughes (b. 1917)

- Judith Kanakuze (b. 1959)

- Wu Zhonghua (d. 1992)

Nacotchtank

[edit]The Nacotchtank, also Anacostine,[1] were an Algonquian Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands.

During the 17th century, the Nacotchtank resided within the present-day borders of Washington, D.C., along the intersection of the Potomac and Anacostia rivers.[2]

The Nacotchtank spoke Piscataway, a variant of the Algonquian subfamily spoken by many tribes along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean.[3] This was due to close association and tribute with the nearby Piscataway chiefdom, whose tayac (grand chief) ruled over a loose confederacy of tribes in Southern Maryland from the village of Moyaone to the south.[4][5]

As the neighboring Maryland colony sought land for tobacco plantations, the Nacotchtank were encroached upon and forcibly removed.[5] They were last recorded in the late 1600s to have taken refuge on nearby Theodore Roosevelt Island located in the Potomac River.[6] Over time, the small population that was left behind after battle and disease was absorbed into the Piscataway.[6]

In his 1608 expedition, English explorer John Smith noted the prosperity of the Nacotchtank and their great supply of various resources.[7] Various pieces of art and other cultural artifacts, including hair combs, pendants, pottery, and dog bones, have been found in excavations throughout Washington, D.C., on Nacotchtank territory.[8]

The chorus is the established National Anthem.

| Irish version | IPA transcription | English version |

|---|---|---|

Sinne Fianna Fáil,[fn 1] |

[ˈʃɪ.n̠ʲə ˈfʲi(ə).n̪ˠə ˈfˠɑːlʲ] |

Soldiers are we, |

- ^ Literally "We are the Fianna [see Fenian Cycle] of Fál [see Lia Fáil]"

- ^ Rather than the standard Irish forms faoi and faoin, National Anthems of the World has fé and fé'n respectively,[9] which reflects the Munster Irish variants[10][11] used in the originally published lyrics.[12]

- ^ Literal translation: "For love of the Gael, towards death or life"

- ^ canaíg or canaidh, the form used in the original Irish translation of the song published by Ó Rinn[12] is a Munster Irish variant of the standard form canaigí. As the standard form would not fit the meter the unusual form canaig' used by The Department of the Taoiseach is evidently an abbreviation of canaigí.

- ^ Kearney's original, otherwise English, text, includes bearna bhaoil, Irish for "gap of danger".[13]

Passamaquoddy

[edit]

Settlers of European descent repeatedly forced the Passamaquoddy off their original lands from the 1800s. After the United States achieved independence from Great Britain, the tribe was eventually officially limited to the current Indian Township Reservation, at , in eastern Washington County, Maine. It has a land area of 37.45 square miles (97.0 km2) and a 2000 census resident population of 676 persons. They also control the small Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation in eastern Washington County, which has a land area of 0.5 square miles (1.3 km2) and a population of 749, per the 2010 census.[15]

Passamaquoddy have also lived on off-reservation trust lands in five Maine counties. These lands total almost four times the size of the reservations proper. They are located in northern and western Somerset County, northern Franklin County, northeastern Hancock County, western Washington County, and several locations in eastern and western Penobscot County. The total land area of these areas is 373.888 km2 (144.359 sq mi). As of the 2000 census, no residents were on these trust lands.

The Passamaquoddy also live in Charlotte County, New Brunswick, Canada, where they have a chief and organized government. They maintain active land claims in Canada but do not have legal status there as a First Nation. Some Passamaquoddy continue to seek the return of territory now within present-day St. Andrews, New Brunswick, which they claim as Qonasqamkuk, a Passamaquoddy ancestral capital and burial ground.

Diseases brought the Europeans

[edit]

Early explanations for the population decline of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas include the brutal practices of the Spanish conquistadores, as recorded by the Spaniards themselves, such as the encomienda system, which was ostensibly set up to protect people from warring tribes as well as to teach them the Spanish language and the Catholic religion, but in practice was tantamount to serfdom and slavery.[16] The most notable account was that of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whose writings vividly depict Spanish atrocities committed in particular against the Taínos.[17] The second European explanation was a perceived divine approval, in which God removed the Indigenous peoples as part of His "divine plan" to make way for a new Christian civilization. Many Native Americans viewed their troubles in a religious framework within their own belief systems.[18]

According to later academics such as Noble David Cook, a community of scholars began "quietly accumulating piece by piece data on early epidemics in the Americas and their relation to the subjugation of native peoples." Scholars like Cook believe that widespread epidemic disease, to which the Indigenous peoples had no prior exposure or resistance, was the primary cause of the massive population decline of the Native Americans.[19] One of the most devastating diseases was smallpox, but other deadly diseases included typhus, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, cholera, malaria, tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever, and pertussis, which were chronic in Eurasia.[20]

However, recently scholars have studied the link between physical colonial violence such as warfare, displacement, and enslavement, and the proliferation of disease among Native populations.[21][22][23] For example, according to Coquille scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker, "In recent decades, however, researchers challenge the idea that disease is solely responsible for the rapid Indigenous population decline. The research identifies other aspects of European contact that had profoundly negative impacts on Native peoples' ability to survive foreign invasion: war, massacres, enslavement, overwork, deportation, the loss of will to live or reproduce, malnutrition and starvation from the breakdown of trade networks, and the loss of subsistence food production due to land loss."[24]

Further, Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis points out that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, implying that, until that date, epidemic disease played no significant part in the depopulation of the Antilles. The practices of forced labor, brutal punishment, and inadequate necessities of life, were the initial and major reasons for depopulation.[25] Jason Hickel estimates that a third of Arawak workers died every six months from forced labor in these mines.[26] In this way, "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the Indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, as it set the conditions for diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and malaria to flourish.[25] Unlike the populations of Europe who rebounded following the Black Death, no such rebound occurred for the Indigenous populations.[25]

Similarly, historian Jeffrey Ostler at the University of Oregon has argued that population collapses in North America throughout colonization were not due mainly to lack of Native immunity to European disease. Instead, he claims that "When severe epidemics did hit, it was often less because Native bodies lacked immunity than because European colonialism disrupted Native communities and damaged their resources, making them more vulnerable to pathogens." In specific regard to Spanish colonization of northern Florida and southeastern Georgia, Native peoples there "were subject to forced labor and, because of poor living conditions and malnutrition, succumbed to wave after wave of unidentifiable diseases." Further, in relation to British colonization in the Northeast, Algonquian speaking tribes in Virginia and Maryland "suffered from a variety of diseases, including malaria, typhus, and possibly smallpox." These diseases were not solely a case of Native susceptibility, however, because "as colonists took their resources, Native communities were subject to malnutrition, starvation, and social stress, all making people more vulnerable to pathogens. Repeated epidemics created additional trauma and population loss, which in turn disrupted the provision of healthcare." Such conditions would continue, alongside rampant disease in Native communities, throughout colonization, the formation of the United States, and multiple forced removals, as Ostler explains that many scholars "have yet to come to grips with how U.S. expansion created conditions that made Native communities acutely vulnerable to pathogens and how severely disease impacted them. ... Historians continue to ignore the catastrophic impact of disease and its relationship to U.S. policy and action even when it is right before their eyes."[27]

Historian David Stannard says that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and "unintended consequence" of human migration and progress," and asserts that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable," but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem.[28] He also wrote:[29]

...Despite frequent undocumented assertions that disease was responsible for the great majority of indigenous deaths in the Americas, there does not exist a single scholarly work that even pretends to demonstrate this claim on the basis of solid evidence. And that is because there is no such evidence, anywhere. The supposed truism that more native people died from disease than from direct face-to-face killing or from gross mistreatment or other concomitant derivatives of that brutality such as starvation, exposure, exhaustion, or despair is nothing more than a scholarly article of faith...

In contrast, historian Russel Thornton has pointed out that there were disastrous epidemics and population losses during the first half of the sixteenth century "resulting from incidental contact, or even without direct contact, as disease spread from one American Indian tribe to another."[30] Thornton has also challenged higher Indigenous population estimates, which are based on the Malthusian assumption that "populations tend to increase to, and beyond, the limits of the food available to them at any particular level of technology."[31]

The European colonization of the Americas resulted in the deaths of so many people it contributed to climatic change and temporary global cooling, according to scientists from University College London.[32][33] A century after the arrival of Christopher Columbus, some 90% of Indigenous Americans had perished from "wave after wave of disease", along with mass slavery and war, in what researchers have described as the "great dying".[34] According to one of the researchers, UCL Geography Professor Mark Maslin, the large death toll also boosted the economies of Europe: "the depopulation of the Americas may have inadvertently allowed the Europeans to dominate the world. It also allowed for the Industrial Revolution and for Europeans to continue that domination."[35]

Biological warfare

[edit]When Old World diseases were first carried to the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, they spread throughout the southern and northern hemispheres, leaving the Indigenous populations in near ruins.[20][36] No evidence has been discovered that the earliest Spanish colonists and missionaries deliberately attempted to infect the American Natives, and some efforts were made to limit the devastating effects of disease before it killed off what remained of their labor force (compelled to work under the encomienda system).[20][36] The cattle introduced by the Spanish contaminated various water reserves which Native Americans dug in the fields to accumulate rainwater. In response, the Franciscans and Dominicans created public fountains and aqueducts to guarantee access to drinking water.[37] But when the Franciscans lost their privileges in 1572, many of these fountains were no longer guarded and so deliberate well poisoning may have happened.[37] Although no proof of such poisoning has been found, some historians believe the decrease of the population correlates with the end of religious orders' control of the water.[37]

In following centuries, accusations and discussions of biological warfare were common. Well-documented accounts of incidents involving both threats and acts of deliberate infection are very rare, but may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged.[38][39] Many of the instances likely went unreported, and it is possible that documents relating to such acts were deliberately destroyed,[39] or sanitized.[40][41] By the middle of the 18th century, colonists had the knowledge and technology to attempt biological warfare with the smallpox virus. They well understood the concept of quarantine, and that contact with the sick could infect the healthy with smallpox, and those who survived the illness would not be infected again. Whether the threats were carried out, or how effective individual attempts were, is uncertain.[20][39][40]

One such threat was delivered by fur trader James McDougall, who is quoted as saying to a gathering of local chiefs, "You know the smallpox. Listen: I am the smallpox chief. In this bottle I have it confined. All I have to do is to pull the cork, send it forth among you, and you are dead men. But this is for my enemies and not my friends."[42] Likewise, another fur trader threatened Pawnee Indians that if they didn't agree to certain conditions, "he would let the smallpox out of a bottle and destroy them." The Reverend Isaac McCoy was quoted in his History of Baptist Indian Missions as saying that the white men had deliberately spread smallpox among the Indians of the southwest, including the Pawnee tribe, and the havoc it made was reported to General Clark and the Secretary of War.[42][43] Artist and writer George Catlin observed that Native Americans were also suspicious of vaccination, "They see white men urging the operation so earnestly they decide that it must be some new mode or trick of the pale face by which they hope to gain some new advantage over them."[44] So great was the distrust of the settlers that the Mandan chief Four Bears denounced the white man, whom he had previously treated as brothers, for deliberately bringing the disease to his people.[45][46][47]

During the siege of British-held Fort Pitt in the Seven Years' War, Colonel Henry Bouquet ordered his men to take smallpox-infested blankets from their hospital and gave them as gifts to two neutral Lenape Indian dignitaries during a peace settlement negotiation, according to the entry in the Captain's ledger, "To convey the Smallpox to the Indians".[40][48][49] In the following weeks, Sir Jeffrey Amherst conspired with Bouquet to "Extirpate this Execreble Race" of Native Americans, writing, "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them." His Colonel agreed to try.[39][48]

Most scholars have asserted that the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic was "started among the tribes of the upper Missouri River by failure to quarantine steamboats on the river",[42] and Captain Pratt of the St. Peter "was guilty of contributing to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. The law calls his offense criminal negligence. Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences."[46] However, some sources attribute the 1836–40 epidemic to the deliberate communication of smallpox to Native Americans, with historian Ann F. Ramenofsky writing, "Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets. In the nineteenth century, the U. S. Army sent contaminated blankets to Native Americans, especially Plains groups, to control the Indian problem."[50] In Brazil, well into the 20th century, deliberate infection attacks continued as Brazilian settlers and miners transported infections intentionally to the Native groups whose lands they coveted.[36]

Vaccination

[edit]After Edward Jenner's 1796 demonstration that the smallpox vaccination worked, the technique became better known and smallpox became less deadly in the United States and elsewhere. Many colonists and Natives were vaccinated, although, in some cases, officials tried to vaccinate Natives only to discover that the disease was too widespread to stop. At other times, trade demands led to broken quarantines. In other cases, Natives refused vaccination because of suspicion of whites. The first international healthcare expedition in history was the Balmis Expedition which had the aim of vaccinating Indigenous peoples against smallpox all along the Spanish Empire in 1803. In 1831, government officials vaccinated the Yankton Dakota at Sioux Agency. The Santee Sioux refused vaccination and many died.[51]

Pericú

[edit]

The Jesuits established their first permanent mission in Baja California at Loreto in 1697, but it was more than two decades later that they felt prepared to move into the Cape Region. Missions serving the Pericú, at least in part, were established at La Paz (1720), Santiago (1724), and San José del Cabo (1730). A dramatic reversal came in 1734 when the Pericú Revolt began, resulting in the most serious challenge the Jesuits experienced in Baja California. Two missionaries were killed, and for two years Jesuit control over the Cape Region was interrupted.[52][page needed] The Pericú themselves suffered most, however, with combat deaths added to the already devastating effects of Old World diseases. By the time the Spanish crown expelled the Jesuits from Baja California in 1768, the Pericú seem to have been culturally extinct, although some of their genes may survive in local mestizo populations.

Wichita

[edit]The Wichita had a large population in the time of Coronado and Oñate. One scholar estimates their numbers at 200,000.[53] Villages often contained around 1,000 to 1,250 people per village.[54] Certainly they numbered in the tens of thousands. They appeared to be much reduced by the time of the first French contacts with them in 1719, probably due in large part to epidemics of infectious disease to which they had no immunity. In 1790, it was estimated there were about 3,200 total Wichita. Conflict with Texans in the early 19th century and Americans in the mid 19th century led to a major decline in population, leading to the eventual merging of Wichita settlements. By 1868, the population was recorded as being 572 total Wichita. By the time of the census of 1937, there were only 100 Wichita officially left.

In 2018, 2,953 people were enrolled in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes.[55] In 2011, there were 2,501 enrolled Wichitas, 1,884 of whom lived in the state of Oklahoma. Enrollment in the tribe required a minimum blood quantum of 1/32.[56]

Coast Salish

[edit]The first smallpox epidemic to hit the region was in the 1680s, with the disease travelling overland from Mexico by intertribal transmission.[57] Among losses due to diseases, and a series of earlier epidemics that had wiped out many peoples entirely, e.g. the Snokomish in 1850, a smallpox epidemic broke out among the Northwest tribes in 1862, killing roughly half the affected native populations, in some cases up to 90% or more. The smallpox epidemic of 1862 started when an infected miner from San Francisco stopped in Victoria on his way to the Cariboo Gold Rush.[58] As the epidemic spread, police, supported by gunboats, forced thousands of First Nations people living in encampments around Victoria to leave and many returned to their home villages which spread the epidemic. Some consider the decision to force First Nations people to leave their encampments an intentional act of genocide.[59] Mean population decline 1774–1874 was about 66%.[60] Though the Salish peoples together are less numerous than the Cherokee or Navajo, the numbers shown below represent a small fraction of the group.

- Pre-epidemics about 12,600; Lushootseed about 11,800, Twana about 800.

- 1850: about 5,000.

- 1885: less than 2,000, probably not including all the off-reservation populations.

- 1984: sum total about 18,000; Lushootseed census 15,963; Twana 1,029.[61]

- 2013: an estimate of at least 56,590, made up of 28,406 Status Indians registered to Coast Salish bands in British Columbia, and 28,284 enrolled members of Coast Salish Tribes in Washington state.

Tonkawa

[edit]Recent research indicates that as of 1601 the tribe inhabited what is now northwestern Oklahoma.[62] By 1700, Apache and Wichita enemies had pushed the Tonkawa south to the Red River which forms the border between current-day Oklahoma and Texas. In the 16th century, the Tonkawa tribe probably had around 1,900 members. Their numbers diminished to around 1,600 by the late 17th century due to fatalities from European diseases and conflict with other tribes, most notably the Apache.

In the 1740s, some Tonkawa were involved with the Yojuanes and others as settlers in the San Gabriel Missions of Texas along the San Gabriel River.[63]

In 1758, the Tonkawa along with allied Bidais, Caddos, Wichitas, Comanches, and Yojuanes went to attack the Lipan Apache in the vicinity of Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá, which they destroyed.[64]

The tribe continued their southern migration into Texas and northern Mexico, where they allied with the Lipan Apache.[62][65]

In 1824, the Tonkawa entered into a treaty with Stephen F. Austin to protect Anglo-American immigrants against the Comanche. At the time, Austin was an agent recruiting immigrants to settle in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Texas. In 1840 at the Battle of Plum Creek and again in 1858 at the Battle of Little Robe Creek, the Tonkawa fought alongside the Texas Rangers against the Comanche.[66]

The Tonkawas often visited the capital city of Austin during the days of the Republic of Texas and during early statehood.[67]

In 1859, the United States removed the Tonkawa and a number of other Texas Indian tribes to the Wichita Agency in Indian Territory, and placed them under the protection of nearby Fort Cobb. When the American Civil War started in 1861, Texas declared for the Confederacy, so the federal troops at the fort received orders to march to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, leaving the Indians at the Wichita Agency unprotected.

In response to years of animosity (in part regarding rumors that the Tonkawas engaged in ritual cannibalism against defeated enemies [68][69] ), a number of pro-Union tribes, including the Delawares, Wichitas, and Penateka Comanches, attacked the Tonkawas in 1862 as they tried to escape.[70] The fight, known as the Tonkawa Massacre killed nearly half of the remaining Tonkawas, leaving them with little more than 100 people.

The tribe returned to Fort Griffin, Texas where they remained for the rest of the Civil War. After the war, the tribe was returned to Texas.

In October, 1884, the United States removed them, once again, to the new Oakland Agency in northern Indian Territory, where they have remained. This journey involved going to Cisco, Texas, where they boarded a railroad train that took them to Stroud in Indian Territory, where they spent the winter at the Sac and Fox Agency. The Tonkawas travelled 100 miles (160 km) to the Ponca Agency, and arrived at nearby Fort Oakland on June 30, 1885.[a]

On October 21, 1891, the tribe signed an agreement with the Cherokee Commission to accept individual allotments of land.[72]

By 1921, only 34 tribal members remained. Their numbers have since increased to close to 950 as of 2023.[73] The Tonkawa Tribe of Oklahoma incorporated under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act in 1938.[71]

A 60-acre property (24 ha), was purchased by the Tonkawa Tribe in 2023 in commemoration of its status as a site sacred to the Tonkawa.[74] Sugarloaf Mountain, the highest point in Milam County, Texas, will become part of a historical park.[75]

Disappear this Native American tribe

[edit]After thousands of years of different indigenous cultures in present-day Virginia, the Manahoac and other Piedmont tribes developed from the prehistoric Woodland cultures. Historically the Siouan tribes occupied more of the Piedmont area, and the Algonquian-speaking tribes inhabited the lowlands and Tidewater.

In 1608 the English explorer John Smith met with a sizable group of Manahoac above the falls of the Rappahannock River. He recorded that they were living in at least seven villages to the west of where he had met them. He also noted that they were allied with the Monacan, but opposed to the Powhatan. (The historic Manahoac and Monacan tribes were both Siouan-speaking, which gave them some shared culture and was part of the reason they competed with the Algonquian-speaking tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy.)

As the Beaver Wars upset the balance of power, some Manahoac settled in Virginia near the Powhatans. In 1656, these Manahoac fended off an attack by English and Pamunkey, resulting in the Battle of Bloody Run (1656).

By the 1669 census, because of raids by enemy Iroquois tribes from the north (during the Beaver Wars) and probably infectious disease from European contact, the Manahoac were reduced to only fifty bowmen in their former area. Their surviving people apparently joined their Monacan allies to the south immediately afterward. John Lederer recorded the "Mahock" along the James River in 1670. In 1671 Lederer passed directly through their former territory and made no mention of any inhabitants. Around the same time, the Seneca nation of the Iroquois began to claim the land as their hunting grounds by right of conquest, though they did not occupy it.[76][77][78]

In 1714, Lt. Governor of Virginia Alexander Spotswood recorded that the Stegaraki subtribe of the Manahoac was present at Fort Christanna in Brunswick County. The fort was created by Spotswood and sponsored by the College of William and Mary to convert natives to Christianity and teach them the English language. The other known Siouan tribes of Virginia were all represented by members at Fort Christanna.

The anthropologist John Swanton believed that a group at Fort Christanna, called the Mepontsky, were perhaps the Ontponea subtribe of the Manahoac. The last mention of the Ontponea in historic records was in 1723. Scholars believe they joined with the Tutelo and Saponi and became absorbed into their tribes.[76] In 1753, these two tribes were formally adopted in New York by their former enemies, the Iroquois, specifically the Cayuga nation. In 1870, there was a report of a "merry old man named Mosquito" living in Canada, who claimed to be "the last of the Manahoac" and the legal owner of much of northern Virginia. He still remembered how to speak the Siouan language.[79]

Diseases about the Native Americans

[edit]

The arrival and settlement of Europeans in the Americas resulted in what is known as the Columbian exchange. During this period European settlers brought many different technologies, animals, plants, and lifestyles with them, some of which benefited the indigenous peoples[citation needed]. Europeans also took plants and goods back to the Old World. Potatoes and tomatoes from the Americas became integral to European and Asian cuisines, for instance.[80]

But Europeans also unintentionally brought new infectious diseases, including among others smallpox, bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, the common cold, diphtheria, influenza, malaria, measles, scarlet fever, sexually transmitted diseases (with the possible exception of syphilis), typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis (although a form of this infection existed in South America prior to contact),[81] and pertussis.[82][83][84] Each of these resulted in sweeping epidemics among Native Americans, who had disability, illness, and a high mortality rate.[84] The Europeans infected with such diseases typically carried them in a dormant state, were actively infected but asymptomatic, or had only mild symptoms, because Europe had been subject for centuries to a selective process by these diseases. The explorers and colonists often unknowingly passed the diseases to natives.[80] The introduction of African slaves and the use of commercial trade routes contributed to the spread of disease.[85][86]

The infections brought by Europeans are not easily tracked, since there were numerous outbreaks and all were not equally recorded. Historical accounts of epidemics are often vague or contradictory in describing how victims were affected. A rash accompanied by a fever might be smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, or varicella, and many epidemics overlapped with multiple infections striking the same population at once, therefore it is often impossible to know the exact causes of mortality (although ancient DNA studies can often determine the presence of certain microbes).[87] Smallpox was the disease brought by Europeans that was most destructive to the Native Americans, both in terms of morbidity and mortality. The first well-documented smallpox epidemic in the Americas began in Hispaniola in late 1518 and soon spread to Mexico.[80] Estimates of mortality range from one-quarter to one-half of the population of central Mexico.[88]

Native Americans initially believed that illness primarily resulted from being out of balance, in relation to their religious beliefs. Typically, Native Americans held that disease was caused by either a lack of magical protection, the intrusion of an object into the body by means of sorcery, or the absence of the free soul from the body. Disease was understood to enter the body as a natural occurrence if a person was not protected by spirits, or less commonly as a result of malign human or supernatural intervention.[89] For example, Cherokee spiritual beliefs attribute disease to revenge imposed by animals for killing them.[90] In some cases, disease was seen as a punishment for disregarding tribal traditions or disobeying tribal rituals.[91] Spiritual powers were called on to cure diseases through the practice of shamanism.[92] Most Native American tribes also used a wide variety of medicinal plants and other substances in the treatment of disease.[93]

Smallpox

[edit]Smallpox was lethal to many Native Americans, resulting in sweeping epidemics and repeatedly affecting the same tribes. After its introduction to Mexico in 1519, the disease spread across South America, devastating indigenous populations in what are now Colombia, Peru and Chile during the sixteenth century. The disease was slow to spread northward due to the sparse population of the northern Mexico desert region. It was introduced to eastern North America separately by colonists arriving in 1633 to Plymouth, Massachusetts, and local Native American communities were soon struck by the virus. It reached the Mohawk nation in 1634,[94] the Lake Ontario area in 1636, and the lands of other Iroquois tribes by 1679.[95] Between 1613 and 1690 the Iroquois tribes living in Quebec suffered twenty-four epidemics, almost all of them caused by smallpox.[96] By 1698 the virus had crossed the Mississippi, causing an epidemic that nearly obliterated the Quapaw Indians of Arkansas.[91]

The disease was often spread during war. John McCullough, a Delaware captive since July 1756, who was then 15 years old, wrote that the Lenape people, under the leadership of Shamokin Daniel, "committed several depredations along the Juniata; it happened to be at a time when the smallpox was in the settlement where they were murdering, the consequence was, a number of them got infected, and some died before they got home, others shortly after; those who took it after their return, were immediately moved out of the town, and put under the care of one who had the disease before."[97][98][99][100]

By the mid-eighteenth century the disease was affecting populations severely enough to interrupt trade and negotiations. Thomas Hutchins, in his August 1762 journal entry while at Ohio's Fort Miami, named for the Mineamie people, wrote:

The 20th, The above Indians met, and the Ouiatanon Chief spoke in behalf of his and the Kickaupoo Nations as follows: "Brother, We are very thankful to Sir William Johnson for sending you to enquire into the State of the Indians. We assure you we are Rendered very miserable at Present on Account of a Severe Sickness that has seiz'd almost all our People, many of which have died lately, and many more likely to Die..." The 30th, Set out for the Lower Shawneese Town and arriv'd 8th of September in the afternoon. I could not have a meeting with the Shawneese the 12th, as their People were Sick and Dying every day.[101]

On June 24, 1763, during the siege of Fort Pitt, as recorded in his journal by fur trader and militia captain William Trent, dignitaries from the Delaware tribe met with British officials at the fort, warned them of "great numbers of Indians" coming to attack the fort, and pleaded with them to leave the fort while there was still time. The commander of the fort, Simeon Ecuyear, refused to abandon the fort. Instead, Ecuyear gave as gifts two blankets, one silk handkerchief and one piece of linen that were believed to have been in contact with smallpox-infected individuals, to the two Delaware emissaries Turtleheart and Mamaltee, allegedly in the hope of spreading the deadly disease to nearby tribes, as attested in Trent's journal.[102][103][104][105][106] The dignitaries were met again later and they seemingly hadn't contracted smallpox.[107] A relatively small outbreak of smallpox had begun spreading earlier that spring, with a hundred dying from it among Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes area through 1763 and 1764.[107] The effectiveness of the biological warfare itself remains unknown, and the method used is inefficient compared to airborne transmission.[108][109]

21st-century scientists such as V. Barras and G. Greub have examined such reports. They say that smallpox is spread by respiratory droplets in personal interaction, not by contact with fomites, such objects as were described by Trent. The results of such attempts to spread the disease through objects are difficult to differentiate from naturally occurring epidemics.[110][111]

Gershom Hicks, held captive by the Ohio Country Shawnee and Delaware between May 1763 and April 1764, reported to Captain William Grant of the 42nd Regiment "that the Small pox has been very general & raging amongst the Indians since last spring and that 30 or 40 Mingoes, as many Delawares and some Shawneese Died all of the Small pox since that time, that it still continues amongst them".[112]

19th century

[edit]In 1832 President Andrew Jackson signed Congressional authorization and funding to set up a smallpox vaccination program for Indian tribes. The goal was to eliminate the deadly threat of smallpox to a population with little or no immunity, and at the same time exhibit the benefits of cooperation with the government.[113] In practice there were severe obstacles. The tribal medicine men launched a strong opposition, warning of white trickery and offering an alternative explanation and system of cure. Some taught that the affliction could best be cured by a sweat bath followed by a rapid plunge into cold water.[114][115] Furthermore the vaccines often lost their potency when transported and stored over long distances with primitive storage facilities. It was too little and too late to avoid the great smallpox epidemic of 1837 to 1840 that swept across North America west of the Mississippi, all the way to Canada and Alaska. Deaths have been estimated in the range of 100,000 to 300,000, with entire tribes wiped out. Over 90 percent of the Mandans died.[116][117][118]

In the mid to late nineteenth century, at a time of increasing European-American travel and settlement in the West, at least four different epidemics broke out among the Plains tribes between 1837 and 1870.[82] When the Plains tribes began to learn of the "white man's diseases", many intentionally avoided contact with them and their trade goods. But the lure of trade goods such as metal pots, skillets, and knives sometimes proved too strong. The Indians traded with the white newcomers anyway and inadvertently spread disease to their villages.[119] In the late 19th century, the Lakota Indians of the Plains called the disease the "rotting face sickness".[91][119]

The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic, which was brought from San Francisco to Victoria, devastated the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, with a death rate of over 50% for the entire coast from Puget Sound to Southeast Alaska.[120] In some areas the native population fell by as much as 90%.[121][122] Some historians have described the epidemic as a deliberate genocide because the Colony of Vancouver Island and the Colony of British Columbia could have prevented the epidemic but chose not to, and in some ways facilitated it.[121][123]

Effect on population numbers

[edit]

Many Native American tribes suffered high mortality and depopulation, averaging 25–50% of the tribes' members dead from disease. Additionally, some smaller tribes neared extinction after facing a severely destructive spread of disease.[82]

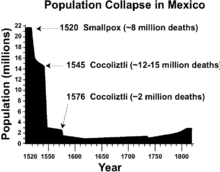

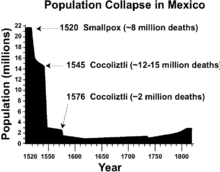

A specific example was what followed Cortés' invasion of Mexico. Before his arrival, the Mexican population is estimated to have been around 25 to 30 million. Fifty years later, the Mexican population was reduced to 3 million, mainly by infectious disease. A 2018 study by Koch, Brierley, Maslin and Lewis concluded that an estimated "55 million indigenous people died following the European conquest of the Americas beginning in 1492."[124] Estimates for the entire number of human lives lost during the Cocoliztli epidemics in New Spain have ranged from 5 to 15 million people,[125] making it one of the most deadly disease outbreaks of all time.[126] By 1700, fewer than 5,000 Native Americans remained in the southeastern coastal region of the United States.[84] In Florida alone, an estimated 700,000 Native Americans lived there in 1520, but by 1700 the number was around 2,000.[84]

Some 21st-century climate scientists have suggested that a severe reduction of the indigenous population in the Americas and the accompanying reduction in cultivated lands during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries may have contributed to a global cooling event known as the Little Ice Age.[124][127]

The loss of the population was so high that it was partially responsible for the myth of the Americas as "virgin wilderness". By the time significant European colonization was underway, native populations had already been reduced by 90%. This resulted in settlements vanishing and cultivated fields being abandoned. Since forests were recovering, the colonists had an impression of a land that was an untamed wilderness.[128]

Disease had both direct and indirect effects on deaths. High mortality meant that there were fewer people to plant crops, hunt game, and otherwise support the group. Loss of cultural knowledge transfer also affected the community as vital agricultural and food-gathering skills were not passed on to survivors. Missing the right time to hunt or plant crops affected the food supply, thus further weakening the community and making it more vulnerable to the next epidemic. Communities under such crisis were often unable to care for people who were disabled, elderly, or young.[84]

In summer 1639, a smallpox epidemic struck the Huron natives in the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes regions. The disease had reached the Huron tribes through French colonial traders from Québec who remained in the region throughout the winter. When the epidemic was over, the Huron population had been reduced to roughly 9,000 people, about half of what it had been before 1634.[129] The Iroquois people, generally south of the Great Lakes, faced similar losses after encounters with French, Dutch and English colonists.[84]

During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% (tens of thousands) of the Northwestern Native Americans.[130][131] The smallpox epidemic of 1780–1782 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[132]

By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[133] The Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1839 reported on the casualties of the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic: "No attempt has been made to count the victims, nor is it possible to reckon them in any of these tribes with accuracy; it is believed that if [the number 17,200 for the upper Missouri River Indians] was doubled, the aggregate would not be too large for those who have fallen east of the Rocky Mountains."[134]

Historian David Stannard asserts that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and 'unintended consequence' of human migration and progress." He says that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable", but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem.[135] Historian Andrés Reséndez says that evidence suggests "among these human factors, slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, rather than diseases such as smallpox, influenza and malaria.[136]

Diseases about New Spain

[edit]The role of epidemics

[edit]

Spanish settlers brought to the American continent smallpox, measles, typhoid fever, and other infectious diseases. Most of the Spanish settlers had developed an immunity to these diseases from childhood, but the indigenous peoples lacked the needed antibodies since these diseases were totally alien to the native population. There were at least three separate, major epidemics that devastated the population: smallpox (1520–1521), measles (1545–1548) and typhus (1576–1581).

During the 16th century, the native population of Mexico fell from an estimated pre-Columbian population of 8 to 20 million to less than two million. Therefore, at the start of the 17th century, continental New Spain was a depopulated region with abandoned cities and maize fields. These diseases did not affect the Philippines in the same way because they were already present; Pre-Hispanic Filipinos had contact with other foreign nationalities prior to the arrival of the Spaniards.

Population in early 1800s

[edit]

While different intendancies would conduct censuses to get insights into their inhabitants (namely occupation, number of persons per household, ethnicity etc.), it was not until 1793 that the results of the first national census would be published. That census is known as the "Revillagigedo census" because its creation was ordered by the Count of the same name. Most of the census' original datasets have reportedly been lost; thus most of what is known about it comes from essays and field investigations made by academics who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works, such as Prussian geographer Alexander von Humboldt. Each author gives different estimates for the total population, ranging from 3,799,561 to 6,122,354[137][138] (more recent data suggest that the population of New Spain in 1810 was 5 to 5.5 million individuals)[139] and not much variation in ethnic composition, with Europeans ranging from 18% to 23% of New Spain's population, Mestizos ranging from 21% to 25%, Amerindians ranging from 51% to 61% and Africans being between 6,000 and 10,000. It is concluded then, that across nearly three centuries of colonization, the population growth trends of Europeans and Mestizos were steady, while the percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%–17% per century. The authors assert that rather than Europeans and Mestizos having higher birthrates, the reason for the indigenous population's decrease lies with their higher mortality, due to living in remote locations rather than in cities and towns founded by the Spanish colonists, or being at war with them. It is also for these reasons that the number of indigenous Mexicans presents a greater variation between publications, with their numbers in a given location estimated rather than counted, leading to possible overestimations in some provinces and underestimations in others.[140]

| Intendancy/territory | European population (%) | Indigenous population (%) | Mestizo population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| México (only State of Mexico and capital) | 16.9% | 66.1% | 16.7% |

| Puebla | 10.1% | 74.3% | 15.3% |

| Oaxaca | 06.3% | 88.2% | 05.2% |

| Guanajuato | 25.8% | 44.0% | 29.9% |

| San Luis Potosí | 13.0% | 51.2% | 35.7% |

| Zacatecas | 15.8% | 29.0% | 55.1% |

| Durango | 20.2% | 36.0% | 43.5% |

| Sonora | 28.5% | 44.9% | 26.4% |

| Yucatán | 14.8% | 72.6% | 12.3% |

| Guadalajara | 31.7% | 33.3% | 34.7% |

| Veracruz | 10.4% | 74.0% | 15.2% |

| Valladolid | 27.6% | 42.5% | 29.6% |

| Nuevo México | ~ | 30.8% | 69.0% |

| Vieja California | ~ | 51.7% | 47.9% |

| Nueva California | ~ | 89.9% | 09.8% |

| Coahuila | 30.9% | 28.9% | 40.0% |

| Nuevo León | 62.6% | 05.5% | 31.6% |

| Nuevo Santander | 25.8% | 23.3% | 50.8% |

| Texas | 39.7% | 27.3% | 32.4% |

| Tlaxcala | 13.6% | 72.4% | 13.8% |

~Europeans are included within the Mestizo category.

Regardless of the imprecision related to the counting of indigenous peoples living outside of the colonized areas, the effort that New Spain's authorities put into considering them as subjects is worth mentioning, as censuses made by other colonial or post-colonial countries did not consider American Indians to be citizens/subjects. For example the censuses made by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata would only count the inhabitants of the colonized settlements.[141] Another example would be the censuses made by the United States, that did not count Indigenous peoples living among the general population until 1860, and indigenous peoples as a whole until 1900.[142]

Once New Spain achieved independence, the legal basis of the colonial caste system was abolished and mentions of a person's caste in official documents was also abandoned, which led to the exclusion of racial classification from future censuses, and made it difficult to track demographic development of each ethnicity in the country. More than a century would pass before Mexico conducted a new census on which a person's race was listed, in 1921,[143] but even then, due to its huge inconsistencies with other official registers as well as its historic context, modern investigators have deemed it inaccurate.[144][145] Almost a century after the 1921 census, Mexico's government has begun to conduct ethno-racial surveys again, with results suggesting that the population growth trends for each major ethnic group haven't changed significantly since the 1793 census.

Karuk

[edit]The Karuk language originated around the Klamath River between Seiad Valley and Bluff Creek. Before European contact, it is estimated that there may have been up to 1,500 speakers.[146] Linguist William Bright documented the Karuk language. When Bright began his studies in 1949, there were "a couple of hundred fluent speakers," but by 2011, there were fewer than a dozen fluent elders.[147] A standardized system for writing the languages was adopted in the 1980s.[148]

The region where the Karuk tribe lived remained largely undisturbed until beaver trappers came through the area in 1827.[149] In 1848, gold was discovered in California, and thousands of Europeans came to the Klamath River and its surrounding region to search for gold.[149] The Karuk territory was soon filled with mining towns, manufacturing communities, and farms. The salmon that the tribe relied on for food became less plentiful because of contamination in the water from mining, and many members of the Karuk tribe died from either starvation or new diseases that the Europeans brought with them to the area.[149] Many members of the Karuk tribe were also killed or sold into slavery by the Europeans. Karuk children were sent to boarding schools where they were Americanized and told not to use their native language.[149] These combined factors caused the use of the Karuk language to steadily decline over the years until measures were taken to attempt to revitalize the language.

Piscataway

[edit]

The Piscataway /pɪsˈkætəˌweɪ/ pih-SKAT-ə-WAY or Piscatawa /pɪsˈkætəˌweɪ, ˌpɪskəˈtɑːwə/ pih-SKAT-ə-WAY, PIH-skə-TAH-wə,[150] are Native Americans. They spoke Algonquian Piscataway, a dialect of Nanticoke. One of their neighboring tribes, with whom they merged after a massive decline of population following two centuries of interactions with European settlers, called them the Conoy.

Two major groups representing Piscataway descendants received state recognition as Native American tribes in 2012: the Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory[151][152] and the Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland.[151][153] Within the latter group was included the Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Sub-Tribes and the Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians.[151][154] All these groups are located in Southern Maryland. None are federally recognized.

Featured Picture

[edit]

|

W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) was an English dramatist, librettist and illustrator best known for his fourteen comic operas produced in collaboration with the composer Arthur Sullivan. The most popular Gilbert and Sullivan collaborations include H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado, one of the most frequently performed works in the history of musical theatre. These Savoy operas continue to be performed regularly today throughout the English-speaking world and beyond. Gilbert's creative output included more than 75 plays and libretti, numerous stories, poems, lyrics and various other comic and serious pieces. His plays and realistic style of stage direction inspired other dramatists, including Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw, and his comic operas inspired the development of American musical theatre, especially influencing Broadway writers. The journalist Frank M. Boyd wrote of Gilbert: "Till one actually came to know the man, one shared the opinion ... that he was a gruff, disagreeable person; but nothing could be less true of the really great humorist. He had ... precious little use for fools ... but he was at heart as kindly and lovable a man as you could wish to meet." This cabinet card of Gilbert was produced by the photographic studio Elliott & Fry around 1882–1883. Photograph credit: Elliott & Fry; restored by Adam Cuerden

Recently featured:

|

- ^ Burr, Charles R. (1920). "A Brief History of Anacostia, Its Name, Origin and Progress". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 23: 168. ISSN 0897-9049. JSTOR 40067143. Retrieved 2020-10-11 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Native Peoples of Washington, DC (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ Mithun, Marianne (2001-06-07). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-29875-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Herman, Doug (2018-07-04). "American Indians of Washington, D.C., and the Chesapeake". American Association of Geographers. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ a b "Before the White House". The White House Historical Association. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ a b Navarro, Meghan A. "Early Indian Life on Analostan Island | National Postal Museum". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ Mooney, James (1889). "Indian Tribes of the District of Columbia". American Anthropologist. The Aborigines of the District of Columbia and the Lower Potomac - A Symposium, under the Direction of the Vice President of Section D. 2 (3): 259. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 658373. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ Hedgpeth, Dana. "A Native American tribe once called D.C. home. It's had no living members for centuries". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ Reed, W.L.; Bristow, M.J., eds. (1985). National Anthems of the World (6th ed.). Poole: Blandford Press. pp. 234–237. ISBN 0713715251.

- ^ Ó Dónaill, Niall (1977). "fé". Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla. Foras na Gaeilge. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Na Rialacha : 23 I". Litriú na Gaeilge – Lámhleabhar An Chaighdeáin Oifigiúil (in Irish). Dublin: Stationery Office / Oifig an tSoláthair. 1947. p. 26. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ a b Ó Rinn, Liam (3 November 1923). "Aḃrán na ḃFian" (PDF). An T-Óglaċ (in Irish). 1 NS (17). Dublin: 13.

- ^ Victor Meally, ed. (1968). Encyclopaedia of Ireland. A. Figgis. p. 172.

- ^ "Acadia National Park - Wabanaki Ethnography (U.S. National Park Service)". Archived from the original on 2008-08-29. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation, Washington County, Maine". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Encyclopedia of slave resistance and rebellion. Vol. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioLife. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-113-14760-8. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ Guilmet, George M; Boyd, Robert T; Whited, David L; Thompson, Nile (1991). "The Legacy of Introduced Disease: The Southern Coast Salish". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 15 (4): 1–32. doi:10.17953/aicr.15.4.133g8x7135072136.

- ^ Cook, Noble David. Born To Die; Cambridge University Press; 1998; pp. 1–14.

- ^ a b c d The First Horseman: Disease in Human History; John Aberth; Pearson-Prentice Hall (2007); pp. 47–75 (51)

- ^ Edwards, Tai S; Kelton, Paul (2020-06-01). "Germs, Genocides, and America's Indigenous Peoples". Journal of American History. 107 (1): 52–76. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaaa008. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ^ Herzog, Richard (2020-09-23). "How Aztecs Reacted to Colonial Epidemics". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Curthoys, Ann; Docker, John (2001). "Introduction: Genocide: definitions, questions, settler-colonies". Aboriginal History. 25: 1–15. ISSN 0314-8769. JSTOR 45135468.

Some of the worst examples of escalating death by sickness and disease occurred on the Spanish Christian missions in Florida, Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico in the period 1690–1845. After the military delivered captive Indians to the missions, they were expected to perform arduous agricultural labour while being provided with no more than 1400 calories per day in low-nutrient foods, with some missions supplying as little as 715 calories per day.

- ^ Gilio-Whitaker, Dina (2019). As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8070-7378-0. OCLC 1044542033.

- ^ a b c Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-547-64098-3.

- ^ Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-78609-003-4.

- ^ Ostler, Jeffrey (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. Yale University Press. pp. 11–17, 381. ISBN 978-0-300-24526-4.

Since 1992, the argument for a total, relentless, and pervasive genocide in the Americas has become accepted in some areas of Indigenous studies and genocide studies. For the most part, however, this argument has had little impact on mainstream scholarship in U.S. history or American Indian history. Scholars are more inclined than they once were to gesture to particular actions, events, impulses, and effects as genocidal, but genocide has not become a key concept in scholarship in these fields.

- ^ David E. Stannard (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- ^ Stannard, David E. (1996). Uniqueness as Denial: The Politics of Genocide Scholarship. Westview Press. p. 255. ISBN 0-8133-2641-9.

- ^ Thomas Michael Swensen (2015). "Of Subjection and Sovereignty: Alaska Native Corporations and Tribal Governments in the Twenty-First Century". Wíčazo Ša Review. 30 (1): 100. doi:10.5749/wicazosareview.30.1.0100. ISSN 0749-6427. S2CID 159338399.

- ^ Russel, Thornton (1994). "Book reviews – American Holocaust: Columbus and the Conquest of the New World by David E. Stannard". The Journal of American History. 80 (4): 1428. doi:10.2307/2080617. JSTOR 2080617.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (31 January 2019). "America colonisation 'cooled Earth's climate'". BBC. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- ^ Maslin, Mark; Lewis, Simon (25 June 2020). "Why the Anthropocene began with European colonisation, mass slavery and the 'great dying' of the 16th century". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Kent, Lauren (1 February 2019). "European colonizers killed so many Native Americans that it changed the global climate, researchers say". CNN. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Cook; pp. 205–16

- ^ a b c "La catastrophe démographique" (The Demographic Catastrophe"), L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Empire of Fortune; Francis Jennings; W. W. Norton & Company; 1988; pp. 200, 447–48

- ^ a b c d Fenn, Elizabeth A. Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine; The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 4, March 2000

- ^ a b c The Tainted Gift; Barbara Alice Mann; ABC-CLIO; 2009; pp. 1–18

- ^ Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs: An Indigenous Nation's Fight Against Smallpox, 1518–1824; Paul Kelton; University of Oklahoma Press; 2015; pp. 102–05

- ^ a b c The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian; Esther Wagner Stearn, Allen Edwin Stearn; University of Minnesota; 1945; pp. 13–20, 73–94, 97

- ^ Chardon's Journal at Fort Clark, 1834–1839; Annie Heloise Abel; Books for Libraries Press; 1932; pp. 319, 394

- ^ Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History; Donald R. Hopkins; University of Chicago Press; 1983; pp. 270–71

- ^ Robert Blaisdell ed., Great Speeches by Native Americans, p. 116.

- ^ a b Rotting Face: Smallpox and the American Indian; R. G. Robertson; Caxton Press; 2001 pp. 80–83; 298–312

- ^ Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present; George C. Kohn; pp. 252–53

- ^ a b Pontiac and the Indian Uprising; Peckham, Howard H.; University of Chicago Press; 1947; pp. 170, 226–27

- ^ Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766; Anderson, Fred; New York: Knopf; 2000; pp. 541–42, 809 n11; ISBN 0-375-40642-5

- ^ Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact; University of New Mexico Press; 1987; pp. 147–48

- ^ Krech III, Shepard (1999). The Ecological Indian: Myth and History (1 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-0-393-04755-4.

- ^ Taraval (1931).

- ^ Smith, F. "Wichita Locations and Population, 1719-1901. Plains Anthropologist Vol. 53, No. 28, 2008, pp.407-414

- ^ Wedel, Mildred M. 1982a The Wichita Indians in the Arkansas River Basin. In Plains Indian Studies: A Collection of Papers in Honor of John C. Ewers and Waldo R. Wedel, edited by D.H. Ubelaker and H.J. Viola, pp. 118-134. Smithsonian

- ^ Gately, Paul (8 July 2018). "Native Americans chose Waco for water and abundance, like others". 10 KWTX. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Archived April 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2011: 38. Retrieved 8 Feb 2012.

- ^ [The Resettlement of British Columbia, Cole Harris, UBC]

- ^ "The Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 (Victoria BC)--Overview and Timeline".

- ^ "Spirit of Pestilence: The Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 in Victoria BC".

- ^ (1) Lange, Essay 5171)

(2) Boyd (1999)

(2.1) A smallpox vaccine was discovered in 1801. Russian Orthodox missionaries were an exception to general policy and vaccinated at-risk Native populations in what is now SE Alaska and NW British Columbia. [Boyd] - ^ Suttles & Lane (1990), pp. 499–500

- ^ a b May, Jon D. "Tonkawa (tribe)". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Gary Clayton Anderson, The Indian Southwest, 1580-1830: Ethnogenesis and Reinvention (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999) p. 85

- ^ Anderson, The Indian Southwest, p. 89

- ^ Walker, Jeff (2007-11-16). "Chief returns » Local News » San Marcos Record, San Marcos, TX". Sanmarcosrecord.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ^ Gwynne, S. C. (2011). Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. Scribner. pp. 7, 211. ISBN 978-1-4165-9106-1.

- ^ Barnes, Michael "With time, the story of the Tonkawa tribe evolves" The Washington Post (February 13, 2014)

- ^ Jones, William K. 1969. “Notes on the History and Material Culture of the Tonkawa Indians.” Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology. Vol. 2, No. 5.

- ^ Jerry Withers "The Tonkawan Indians of Texas" reprinted by SonsofDewittcolony.org

- ^ : John D. May "Tonkawa Massacre" OKHistory.org

- ^ a b "Tonkawa Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma." Oklahoma State Department of Education. Oklahoma Indian Tribe Education Guide. July 2014. Accessed October 28, 2018.

- ^ Deloria Jr., Vine J; DeMaille, Raymond J (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775-1979. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 346–348. ISBN 978-0-8061-3118-4.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

WTH 2023-12-23was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Miller, Alex (2023-12-23). "How the Tonkawa Tribe bought back sacred Sugarloaf Mountain in Central Texas". Waco Tribune-Herald. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ Barnes, Michael (January 17, 2024). "'We're home': 140 years after forced exile, the Tonkawa reclaim a sacred part of Texas". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ a b Swanton, John R. (1952), The Indian Tribes of North America, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 61–62, hdl:2027/mdp.39015015025854, ISBN 0-8063-1730-2, OCLC 52230544

- ^ Egloff, Keith; Woodward, Deborah (2006), First People: The Early Indians of Virginia, University of Virginia Press, p. 59, ISBN 978-0-8139-2548-6, OCLC 63807988

- ^ Fairfax Harrison, 1924, Landmarks of Old Prince William, p. 25, 33.

- ^ Harrison, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Francis, John M. (2005). Iberia and the Americas culture, politics, and history: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Bos, Kirsten I.; Harkins, Kelly M.; Herbig, Alexander; Coscolla, Mireia; et al. (20 August 2014). "Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis". Nature. 514 (7523): 494–7. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..494B. doi:10.1038/nature13591. PMC 4550673. PMID 25141181.

- ^ a b c Waldman, Carl (2009). Atlas of the North American Indian. New York: Checkmark Books. p. 206.

- ^ Rossi, Ann (2006). Two Cultures Meet: Native American and European. National Geographic Society. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-7922-8679-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Nielsen, Kim (2012). A Disability History of the United States. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2204-7.

- ^ Rodrigo Barquera; Johannes Krause; AJ Zeilstra; Petra Mader (May 9, 2020). "Slavery entailed the spread of epidemics". Max-Planck-Gesellschaft.

- ^ "The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the Introduction of Human Diseases: The Case of Schistosomiasis - Africa Atlanta 2014 Publications". leading-edge.iac.gatech.edu.

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8263-2871-7. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ Hays, J. N.. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. United Kingdom: ABC-CLIO, 2005.

- ^ Vogel, Virgil J. American Indian Medicine. University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

- ^ John Phillip. A law of blood; the primitive law of the Cherokee nation. New York: Northern Illinois University Press, 1970.

- ^ a b c Robertson, R. G. Rotting Face: Smallpox and the American Indian. Caxton Press, 2001.ISBN 0870044974

- ^ Lyon, William S. (1998). Encyclopedia of Native American Healing. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31735-0.

- ^ Moerman, Daniel E. (July 16, 1998). Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-453-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dutch Children's Disease Kills Thousands of Mohawks Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine. Paulkeeslerbooks.com

- ^ Duffy, John (1951). "Smallpox and the Indians in the American Colonies". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 25 (4): 324–341. JSTOR 44443622. PMID 14859018. ProQuest 1296241519.

- ^ Ramenofsky, Ann Felice (1987). Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0997-6.[page needed]

- ^ McCullough, John: The Captivity of John McCullough/ Personally written after eight years of captivity. Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892)Journal of Captain Simeon Ecuyer, Entry June 2, 1763

- ^ McCullough, John: http://The Captivity of John McCullough Personally written after eight years of captivity. Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dixon, David, Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America (pg. 155)

- ^ Hanna, Charles A.: The wilderness trail: or, the ventures and adventures of the Pennsylvania traders on the Allegheny path, with some new annals of the old West, and the records of some strong men and some bad ones (1911) pg.366

- ^ Ewald, Paul W. (2000). Plague Time: How Stealth Infections Cause Cancer, Heart Disease, and Other Deadly Ailments. New York: Free. ISBN 978-0-684-86900-1.

- ^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892). Captain Simeon Ecuyer's Journal: Entry of June 24,1763

- ^ Fenn, Elizabeth A. (2000). "Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst". The Journal of American History. 86 (4): 1552–1580. doi:10.2307/2567577. JSTOR 2567577. PMID 18271127. ProQuest 224890556.

- ^ Flight, Colette (17 February 2011). "Silent Weapon: Smallpox and Biological Warfare". BBC.

- ^ "Tribes - Native Voices". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ a b Ranlet, P (2000). "The British, the Indians, and smallpox: what actually happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?". Pennsylvania History. 67 (3): 427–441. PMID 17216901.

- ^ Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- ^ King, J. C. H. (2016). Blood and Land: The Story of Native North America. Penguin UK. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84614-808-8.

- ^ Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism" (PDF). Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

However, in the light of contemporary knowledge, it remains doubtful whether his hopes were fulfilled, given the fact that the transmission of smallpox through this kind of vector is much less efficient than respiratory transmission, and that Native Americans had been in contact with smallpox >200 years before Ecuyer's trickery, notably during Pizarro's conquest of South America in the 16th century. As a whole, the analysis of the various 'pre-micro-biological' attempts at BW illustrate the difficulty of differentiating attempted biological attack from naturally occurring epidemics.

- ^ Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. Government Printing Office. 2007. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-16-087238-9.

In retrospect, it is difficult to evaluate the tactical success of Captain Ecuyer's biological attack because smallpox may have been transmitted after other contacts with colonists, as had previously happened in New England and the South. Although scabs from smallpox patients are thought to be of low infectivity as a result of binding of the virus in fibrin metric, and transmission by fomites has been considered inefficient compared with respiratory droplet transmission.

- ^ Burke, James P. (May 2009). Pioneers of Second Fork. AuthorHouse. pp. 19–22. ISBN 978-1-4685-3459-7.

- ^ E. Wagner Stearn, and Allen E. Stearn, "Smallpox Immunization of the Amerindian." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 13.5 (1943): 601-613.

- ^ Donald R. Hopkins, The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History (U of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 271.

- ^ Paul Kelton, "Avoiding the Smallpox Spirits: Colonial Epidemics and Southeastern Indian Survival," Ethnohistory 51:1 (winter 2004) pp. 45-71.

- ^ Kristine B. Patterson, and Thomas Runge, "Smallpox and the native American." American journal of the medical sciences 323.4 (2002): 216-222. online

- ^ Dollar, Clyde D. (1977). "The High Plains Smallpox Epidemic of 1837-38". The Western Historical Quarterly. 8 (1): 15–38. doi:10.2307/967216. JSTOR 967216. PMID 11633561.

- ^ Elizabeth A. Fenn, Encounters at the Heart of the World: A History of the Mandan People (2015) ch. 14.

- ^ a b Marshall, Joseph (2005) [2004]. The Journey of Crazy Horse, A Lakota History. Penguin Books.

- ^ Lange, Greg. "Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians". HistoryLink. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b Ostroff, Joshua (August 2017). "How a smallpox epidemic forged modern British Columbia". Maclean's. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Boyd, Robert; Boyd, Robert Thomas (1999). "A final disaster: the 1862 smallpox epidemic in coastal British Columbia". The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline Among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774–1874. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 172–201. ISBN 978-0-295-97837-6. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Swanky, Tom (2013). The True Story of Canada's "War" of Extermination on the Pacific – Plus the Tsilhqot'in and other First Nations Resistance. Dragon Heart Enterprises. pp. 617–619. ISBN 978-1-105-71164-0.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- ^ Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo; et al. (2004). "When half of the population died: the epidemic of hemorrhagic fevers of 1576 in Mexico". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 240 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2004.09.011. PMC 7110390. PMID 15500972.

- ^ Acuna-Soto, R.; Stahle, D. W.; Cleaveland, M. K.; Therrell, M. D (April 2002). "Megadrought and megadeath in 16th century Mexico". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 360–362. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010175. PMC 2730237. PMID 11971767.

- ^ Degroot, Dagomar (2019). "Did Colonialism Cause Global Cooling? Revisiting an Old Controversy". Historical Climatology.

- ^ Denevan, William M. (1992). "The pristine myth: the landscape of the Americas in 1492". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 369–385. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01965.x. JSTOR 2563351.

- ^ Bruce Trigger. Natives and Newcomers: Canada's "Heroic Age" Reconsidered. (Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1985), 588–589.

- ^ Lange, Greg. (2003-01-23) Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s Archived 2008-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. Historyink.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-06.

- ^ Smallpox, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ Houston CS, Houston S (2000). "The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words". Can J Infect Dis. 11 (2): 112–5. doi:10.1155/2000/782978. PMC 2094753. PMID 18159275.

- ^ Pearson, J. Diane (2003). "Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832". Wíčazo Ša Review. 18 (2): 9–35. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0017. S2CID 154875430. Project MUSE 46131.

- ^ The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian; Esther Wagner Stearn, Allen Edwin Stearn; University of Minnesota; 1945; Pgs. 13-20, 73-94, 97

- ^ David E. Stannard (1993-11-18). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-547-64098-3.

- ^ Navarro y Noriega (1820)

- ^ von Humboldt (1811)

- ^ McCaa (2000)

- ^ Lerner, Victoria (1968). Consideraciones sobre la población de la Nueva España: 1793–1810, según Humboldt y Navarro y Noriega [Considerations on the population of New Spain: 1793–1810, according to Humboldt and Navarro and Noriega] (PDF) (in Spanish). pp. 328–348. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Argentina. London: Scarecrow Press, 1978. pp. 239–40.

- ^ "American Indians in the Federal Decennial Census". Retrieved on 25 July 2017.

- ^ Censo General De Habitantes (1921 Census) (PDF) (Report). Departamento de la Estadistica Nacional. p. 62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "El mestizaje es un mito, la identidad cultural sí importa" Istmo, Mexico, Retrieved on 25 July 2017.

- ^ Federico Navarrete (2016). Mexico Racista. Penguin Random house Grupo Editorial Mexico. p. 86. ISBN 978-6073143646. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ "Karuk – Survey of California and Other Indian Languages". linguistics.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ^ Walters, Heidi (October 27, 2011). "In Karuk: A family struggles to bring its ancestral tongue back to life". North Coast Journal. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Karuk language e18was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Bell, Maureen (1991). Karuk : the upriver people. Internet Archive. Happy Camp, CA, U.S.A. : Naturegraph Publishers.

- ^ Proctor, Natalie; and Proctor, Crystal (2014). Interview: Piscataway Indians. DC Women Eco-leaders Project. Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

We are /pɪsˈkætəˌweɪ/ Indians, and that is actually the English way to say the name, and—/ˌpɪskəˈtɑːwə/.

- ^ a b c Witte, Brian (2012-01-09). "Md. Formally Recognizes two American Indian Groups". NBC Washington. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Piscataway Indian Nation and Tayac Territory". (retrieved 4 Jan 2011)

- ^ "Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland". (retrieved 4 Jan 2011)

- ^ "The Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians". Retrieved 4 January 2011.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).