User:Sjanusz/PT2

Philosophical Transactions later Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (Phil. Trans.) is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. It was established in 1665,[1] making it the first journal in the world exclusively devoted to science. It is also the world's longest-running scientific journal. The slightly earlier Journal des sçavans published some science but also contained subject matter from other fields of learning, and its main content type was book reviews.[2][3][4] The use of the word "Philosophical" in the title refers to "natural philosophy", which was the equivalent of what would now be generically called "science".

Current publication

[edit]In 1887 the journal expanded and divided into two separate publications, one serving the Physical Sciences (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Physical, Mathematical and Engineering Sciences) and the other focusing on the life sciences (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences). Both journals now publish themed issues and issues resulting from papers presented at the Discussion Meetings of the Royal Society. Primary research articles are published in the sister journals Proceedings of the Royal Society, Biology Letters, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, and Interface Focus.

Origins and history

[edit]Origins

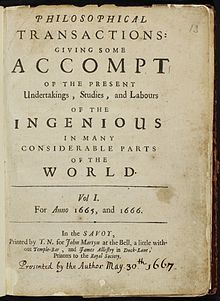

[edit]The first issue, published 6 March 1665, was edited and published by the Society's first secretary, Henry Oldenburg, four-and-a-half years after the Royal Society was founded.[5] Its full title of the journal as given by Oldenburg, "Philosophical Transactions, Giving some Account of the present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours of the Ingenious in many considerable parts of the World". The Society's Council minutes dated 1 March 1664 (in the Julian calendar, equivalent to 1665 in the modern Gregorian system) ordered that "the Philosophical Transactions, to be composed by Mr Oldenburg, be printed the first Munday of every month, if he have sufficient matter for it, and that that tract be licensed by the Council of this Society, being first revised by some Members of the same". Oldenburg published the journal at his own personal expense and seems to have entered into an agreement with the Society's Council allowing him to keep any resulting profits. He was to be disappointed, however, since the journal performed poorly from a financial point of view during his lifetime, just about covering the rent on his house in Piccadilly.[6] Oldenburg put out 136 issues of the Transactions before his death in 1677.[7]

The familiar functions of the scientific journal – Registration (date stamping and provenance), Certification (peer review), Dissemination and Archiving − were introduced at inception by Philosophical Transactions. The beginnings of these ideas can be traced in a series of letters from Oldenburg to Robert Boyle:[8]

- [24/11/1664] We must be very careful as well of regist'ring the person and time of any new matter, as the matter itselfe, whereby the honor of the invention will be reliably preserved to all posterity' (registration and archiving)

- [03/12/1664] '...all ingenious men will thereby be incouraged to impact their knowledge and discoverys' (dissemination)

- The Council minute of 1 March 1665 made provisions for the tract to be revised by members of the Council of the Royal Society, providing the framework for peer review to eventually develop, becoming fully systematic as a process by the 1830s.

The printed journal replaced much of Oldenburg's letter-writing to correspondents, at least on scientific matters, and as such can be seen as a labour-saving device. Oldenburg also described his journal as "one of these philosophical commonplace books", indicating his intention to produce a collective notebook between scientists.[9]

Issue 1 contained such articles as: an account of the improvement of optic glasses; the first report on the Great Red Spot of Jupiter; a prediction on the motion of a recent comet (probably an Oort cloud object); a review of Robert Boyle's 'Experimental History of Cold'; Robert Boyle's own report of a deformed calf; A report of a peculiar lead-ore from Germany, and the use thereof; "Of an Hungarian Bolus, of the Same Effect with the Bolus Armenus; Of the New American Whale-Fishing about the Bermudas," and "A Narrative Concerning the Success of Pendulum-Watches at Sea for the Longitudes". The final article of the issue concerned "The Character, Lately Published beyond the Seas, of an Eminent Person, not Long Since Dead at Tholouse, Where He Was a Councellor of Parliament". The eminent person recently deceased was Pierre de Fermat, although the issue failed to mention the last theorem.[10]

Eighteenth Century and the Society's takeover

[edit]By the mid-eighteenth century, the most notable editors, besides Oldenburg, were Hans Sloane, James Jurin and Cromwell Mortimer.[7] In virtually all cases the journal was edited by the serving secretary of the society (and occasionally by both secretaries working in tandem). Like Oldenburg, these editor-secretaries carried the financial burden of publishing the Philosophical Transactions. By the early 1750s, the journal came under attack, most prominently by John Hill, an actor, apothecary, and naturalist. Hill published three works in two years, ridiculing the Society and its pulication. The Society was quick to point out that it wasn’t officially responsible for the journal, but in 1752 the Society took over the Philosophical Transactions. The journal would henceforth be published “for the sole use and benefit of this Society”; it would be financially carried by the members’ subscriptions; and it would be edited by a Committee of Papers, commensurate with the Society's governing Council.[7]

After the takeover of the journal by the Society, management decisions including negotiating with printers and booksellers, were still the task of one of the Secretaries—but editorial control was exercised through the Committee of Papers. The Committee mostly based its judgements on which papers to publish and which to decline on the 300 to 500-word abstracts of papers read during its weekly meetings. But the members could, if they desired, consult the original paper in full.[7] Once the decision to print had been taken, the paper appeared in the volume for that year. It would feature the author’s name, the name of the Fellow who had communicated the paper to the Society, and the date on which it was read. The Society covered paper, engraving and printing costs.[7] The Society found the journal to be a money-losing proposition: it cost, on average, upwards of £300 annually to produce, of which they seldom recouped more than £150. Because two-fifths of the copies were distributed for free to the journal’s natural market, sales were generally slow, and although back issues sold out gradually it would usually be ten years or more before there were fewer than 100 left of any given print run.[7]

While Joseph Banks was President of the Society (the work of the Committee of Papers continued fairly efficiently, with the President himself in frequent attendance. There was a number of ways in which the President and Secretaries could bypass or subvert the Royal Society’s publishing procedures. Papers could be prevented from reaching the Committee by not allowing them to be read in the first place. Also—though papers were rarely subjected to formal review—there is evidence of editorial intervention, with Banks himself or a trusted deputy proposing cuts or emendations to particular contributions. Publishing in the Philosophical Transactions carried a high degree of prestige and Banks himself attributed an attempt to unseat him, relatively early in his Presidency, to the envy of authors whose papers had been rejected from the journal.[7]

Reform in the Nineteenth Century

[edit]The journal continued steadily through the turn of the century and into the 1820s. In the in the late 1820s and early 1830s, a movement to reform the Royal Society rose. The reformers felt that the scientific character of the Society had been undermined by the admission of too many gentleman dilettantes under Banks. In proposing a more limited membership, to protect the Society’s reputation, they also argued for systematic, expert evaluation of papers for Transactions by named referees.[7]

Sectional Committees, each with responsibility for a particular group of disciplines, were initially set up in the 1830s to adjudicate the award of George IV’s Royal Medals. But individual members of these Committees were soon put to work reporting on and evaluating papers submitted to the Royal Society. These evaluations began to be used as the basis of recommendations to the Committee of Papers, who would then rubber-stamp decisions made by the Sectional Committees. Despite its flaws – it was inconsistent in its application and not free of abuses – this system remained at the heart of the Society’s procedures for publishing until 1847, when the Sectional Committees were dissolved. However, the practice of sending most papers out for review remained.[7]

During the 1850s, the cost of the journal to the Society increased again (and would keep doing so for the rest of the century); illustrations were always the largest outgoing. Illustrations had been a natural and essential aspect of the scientific periodical since the later seventeenth century. Engravings (cut into metal plates) were used for detailed illustrations, particularly where realism was required; while wood-cuts (and, from the early nineteenth century, wood-engravings) were used for diagrams, as they could be easily combined with letterpress.[7]

By the mid-1850s, the Philosophical Transactions was seen as a drain on the Society’s finances and the treasurer, Edward Sabine, urged the Committee of Papers to restrict the length and number of papers published in the journal. In 1852, for example, the amount expended on the Transactions was £1094, but only £276 of this was offset by sales income. Sabine felt this was more than the Society could comfortably sustain. The print run of the journal was 1000 copies. Around 500 of these went to the fellowship, in return for their membership dues, and since authors now received up to 150 off-prints for free, to circulate through their personal networks, the demand for the Transactions through the book trade must have been limited. The concerns with cost eventually led to a change in printer in 1877 from Taylor & Francis to Harrison & Sons – the latter was a larger commercial printer, able to offer the Society a more financially viable contract, although it was less experienced in printing scientific works.[7]

While expenditure was a worry for the Treasurer, as Secretary (from 1854), George Gabriel Stokes was preoccupied with the actual content of the Transactions and his extensive correspondence with authors over his thirty-one-years as Secretary took up most of his time beyond his duties as Lucasian Professor at Cambridge. Stokes was paramount in establishing a more formalised refereeing process at the Royal Society. It was not until Stokes’s Presidency ended, in 1890, that his influence over the journal diminished. The introduction of fixed terms for Society officers precluded subsequent editors from taking on Stokes’s mantle, and meant that the Society operated its editorial practices more collectively than it had done since the mechanisms for it were established in 1752.[7]

By the mid-nineteenth century, the procedure of getting a paper published in the Transactions still relied on the reading of papers by a Fellow. Many papers were sent immediately for printing in abstract form in Proceedings. But those which were being considered for printing in full in Transactions were usually sent to two referees for comment before the final decision was made by the Committee of Papers. During Stokes’s time, authors were given the opportunity to discuss their paper at length with him before, during and after its official submission to the Committee of Papers.[7]

In 1887, the Transactions split into series A and B, dealing with the physical and biological sciences respectively. In 1897, the model of collective responsibility for the editing of the Transactions was emphasized by the re-establishment of the Sectional Committees. The six Sectional Committees covered Mathematics, Botany, Zoology, Physiology, Chemistry & Physics, and Geology, and were composed of Fellows of the Society with relevant expertise. The Sectional Committees took on the task of managing the refereeing process after papers had been read before the Society. Referees were usually Fellows, except in a small number of cases where the topic was beyond the knowledge of the fellowship (or at least, of those willing to referee). The Sectional Committees communicated referee reports to authors; and sent reports to the Committee of Papers for final sanction. The Sectional Committees were intended to reduce the burden on the Secretaries and Council. Consequently, the Secretary in the 1890s, Arthur Rucker no longer coordinated the refereeing of papers, nor did he generally correspond extensively with authors about their papers as Stokes had done. However, he continued to be the first port of call for authors submitting papers.[7]

Twentieth Century

Authors were increasingly expected to submit manuscripts in a standardised format and style. From 1896, they were encouraged to submit typed papers on foolscap-folio-sized paper in order to lighten the work of getting papers ready for printing, and to reduce the chance of error in the process. A publishable paper now had to present its information in an appropriate manner, as well as being of remarkable scientific interest. For a brief period between 1907 and 1914, authors were under even more pressure to conform to the Society’s expectations, due to a decision to discuss cost estimates of candidate papers alongside referees’ reports. The committees could require authors to reduce the number of illustrations or tables or, indeed, the overall length of the paper, as a condition of acceptance. It was hoped that this policy would reduce the still-rising costs of production, which had reached £1747 in 1906; but the effect appears to have been negligible, and the cost estimates ceased to be routine practice after 1914.[7]

It was only after the Second World War that the Society’s concerns about the cost of its journals were finally allayed. There had been a one-off surplus in 1932, but it was only from 1948 that the Transactions began regularly to end the year in surplus. That year, despite a three-fold increase in production costs (it was a bumper year for papers), there was a surplus of almost £400. Part of the post-war financial success of the Transactions was due to the rising subscriptions received, and a growing number of subscriptions from British and international institutions, including universities, industry, and government; this was at the same time as private subscriptions, outside of fellows, were non-existent. By the early 1970s, institutional subscription was the main channel of income from publication sales for the Society. In 1970 – 1971, 43,760 copies of Transactions were sold, of which casual purchasers accounted for only 2070 copies.[7]

All of the Society’s publications now had a substantial international circulation; in 1973, for example, just 11% of institutional subscriptions were from the UK; 50% were from the U.S. Contributions, however, were still mostly from British authors: 69% of Royal Society authors were from the UK in 1974. A Publications Policy Committee suggested that more overseas scientists could be encouraged to submit papers if the requirement to have papers communicated by Fellows was dropped. This did not happen until 1990. There was also a suggestion to create a ‘C’ journal for molecular sciences to attract more authors in that area, but the idea never materialised. The conclusion in 1973 was a general appeal to encourage more British scientists (whether Fellows or not) to publish papers with the Society and to pass on the message to their overseas colleagues; by the early 2000s, the proportion of non-UK authors had risen to around a half; and by 2009 it had passed 70%.[7]

As the twentieth century came to a close, the editing of the Transactions and the Society’s other journals became more professional with the employment of a growing in-house staff of editors, designers and marketers. In 1968 there were about eleven staff in the Publishing Section; in 1990, there was twenty-two staff in the Publishing Section. The editorial processes were also transformed. In 1968 the Sectional Committees had been abolished (again). Instead, the Secretaries, Harrie Steward Massey (physicist) and Bernard Katz (physiologist), were each assigned a group of Fellows to act as Associate Editors for each series (A and B) of the Transactions. The role of the Committee of Papers was abolished in 1989 and since 1990 two Fellows (rather than the Secretaries) have acted as the Editors with assistance from Associate Editors. The Editors serve on the Publishing Board, established in 1997 to monitor publishing and report to the Council. In the 1990s, as these changes to the publishing and editorial teams were implemented, the Publishing Section acquired its first computer for administration; the Transactions went online in 1997.[7]

Famous contributors

[edit]Over the centuries, many important scientific discoveries have been published in the Philosophical Transactions. Famous contributing authors include Isaac Newton, James Clerk Maxwell, Michael Faraday, Edmond Halley and Charles Darwin. In 1672, the journal published Newton's first paper New Theory about Light and Colours,[11] which can be seen as the beginning of his public scientific career. The position of editor was sometimes held jointly and included William Musgrave (Nos 167 to 178) and Robert Plot (Nos 144 to 178).[12]

Pirate Bay episode

[edit]In July 2011 programmer Greg Maxwell released through the The Pirate Bay, the nearly 19 thousand articles that had been published before 1923, and were therefore in the public domain. They had been digitized for the Royal Society by Jstor, for a cost of less than USD100,000, and public access to them was restricted through a paywall.[13][14] In October of the same year, the Royal Society released for free all its articles prior to 1941, but denied that this decision had been influenced by Maxwell's actions. [13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Oldenburg, Henry (1665). "Epistle Dedicatory". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 1: 0–0. doi:10.1098/rstl.1665.0001.

- ^ Banks, David (March 2009). "Starting science in the vernacular. Notes on some early issues of the Philosophical Transactions and the Journal des Sçavans, 1665-1700". ASP. 55. Groupe d'Etude et de Recherche en Anglais de Specialite. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ Banks, David (2010). "The beginnings of vernacular scientific discourse: genres and linguistic features in some early issues of the Journal des Sçavans and the Philosophical Transactions". E-rea. 8 (1). doi:10.4000/erea.1334. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ "Special Collections | The Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology". Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London - History". Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ Bluhm, R. K. (1960). "Henry Oldenburg, F.R.S. (c. 1615-1677)". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 15: 183–126. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1960.0018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Philosophical Transactions: 350 years of publishing at the Royal Society (1665 – 2015)" (PDF).

- ^ Royal Society Archives

- ^ 'Notebooks, Virtuosi and Early-Modern Science' – Richard Yeo

- ^ http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/1/1-22.toc

- ^ Newton, I. (1671). "A Letter of Mr. Isaac Newton, Professor of the Mathematicks in the University of Cambridge; Containing His New Theory about Light and Colors: Sent by the Author to the Publisher from Cambridge, Febr. 6. 1671/72; in Order to be Communicated to the R. Society". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 6 (69–80): 3075–3087. doi:10.1098/rstl.1671.0072.

- ^ A. J. Turner, ‘Plot, Robert (bap. 1640, d. 1696)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ a b Van Noorden, Richard Royal Society frees up journal archive, 26 Oct 2011

- ^ Murphy, y Samantha Guerilla Activist' Releases 18,000 Scientific Papers, July 22, 2011

External links

[edit]- Henry Oldenburg's copy of vol I & II of Philosophical Transactions, manuscript note on a flyleaf, a receipt signed by the Royal Society’s printer: “Rec. October 18th 1669 from Mr Oldenburgh Eighteen shillings for this voll: of Transactions by me John Martyn”.

- Philosophical Transactions (1665-1886) homepage

- Royal Society Publishing

- Index to free volumes and articles online

- Torrent with 18,592 scientific publications in the public domain 32.48 GiB

Category:Publications established in 1665 Category:Royal Society academic journals Category:Multidisciplinary scientific journals Category:Natural philosophy Category:1665 establishments in England