User:Ret.Prof/sandbox5

JOSEPHUS ON JESUS

(Draft edits)

.

Titus Flavius Josephus, was born in the Holy Land about five years after the Crucifixion. Outside of the Bible, the writings of Josephus (c. 37–100) are considered the most important historical documents for understanding the formation Early Christianity. He was a renowned Jewish historian who gave us a detailed history of Palestine at the time of Jesus. The Antiquities of the Jews was written by Josephus from a Jewish or possibly a Jewish Christian (Ebionite) perspective at the end of the First Century. He spoke Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek and resided in Jerusalem at the time of James the Just (the brother of Jesus).

Later Josephus was sent by the Sanhedrin, to command the Jewish military forces in Galilee. Here he witnesses the formation of early Christianity. After 70 CE found favor in Rome where Josephus composed a detailed history of the Hebrew people.

Josephus | |

|---|---|

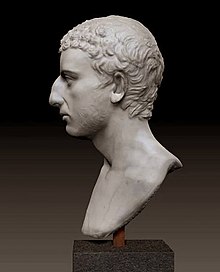

A Roman portrait bust said to be of Josephus | |

| Born | Yosef ben Matityahu 37 AD |

| Died | c. 100 |

| Known for | Writings about the historical Jesus |

| Spouse(s) | Captured Jewish woman Alexandrian Jewish woman Greek Jewish woman from Crete |

| Children | Flavius Hyrcanus Flavius Simonides Agrippa Flavius Justus |

| Parent(s) | Matthias Jewish noblewoman |

Part I: First Century Palestine, Josephus and Jesus

[edit]Early Life and Background

[edit]

Josephus was born in Jerusalem circa 37 CE and died in Rome at about 101 CE. His father and mother belonged to families of the priestly aristocracy; consequently he received an excellent education, becoming knowledgeable about both the Jewish religion and Hebrew culture. At the age of sixteen, he studied with the Essenes for three years, absorbing occult lore, and practicing the ascetic life. Because of his social position, he was expected upon his return to Jerusalem to join the Sadducees. However, being impressed by the outward importance of the Pharisees he attached himself to their party at the age of nineteen. He was also familiar with a Jewish Christian sect led by James the Just. [1] [2] [3] [4]

When war broke out, Josephus was chosen by the Sanhedrin at Jerusalem to be the commander in Galilee, the province where the Roman attack would first fall. Although defeated, he found favor with Titus and accompanied him to Rome. Here he lived the remainder of his days blessed by lavish imperial patronage that enabled him to devote himself to literary pursuits. [5] [6]

The writings of Josephus were designed to "explain and justify" Romans and the Jews to each other. The first work of Josephus was the celebrated "Jewish War" in seven books, originally composed in Aramaic and later expanded and translated into Greek. [7] [8] Of greater importance for historical scholars is the "Jewish Antiquities", which contains the whole history of the Jews from the Creation to the outbreak of the revolt in 66 CE. Because this work contains much that would be offensive to orthodox Jews and Christians some scholars believe Josephus was an Ebionite Jewish-Christian. Nevertheless, the Flavian patronage insured that his books would be copied and preserved in the Roman Empire's public scriptoria. Scholars do not know for certain how many copies were made or to which cities they were sent but by the time of the Emperor Constantine, Christian scribes were also making copies which insured that the works of Josephus were spread throughout the Christian world. Josephus remains "the most reliable witness to Jesus" of any Jewish source. [9] [10] [11] [12]

The three passages

[edit]

"Flavius Josephus is one of the truly important figures from ancient Judaism." His historical writings are our primary source of information about the life and history of first century Palestine. He himself was personally involved with the different religious groups, important events, and controversies of early Christianity. [13]

James the brother of Jesus

[edit]Antiquities of the Jews, Book 20, Chapter 9

| “ | ...Ananus assembled the Sanhedrim of Judges, summoned James (the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ), along with some others. These men were accused of breaking the Law and put to death by stoning | ” |

The James referred to in this passage is most likely James the first Bishop of Jerusalem who was also called James the Just. A couple of years before the Jewish uprising, the powerful High Priest in Jerusalem, misused his authority. The Roman governor had been withdrawn, and in his absence, the High Priest unlawfully put to death a person named James, whom is identified as “the brother of Jesus, who is called the Messiah (Antiquities 20.9.1).

Here, unlike many pagan sources, Jesus is actually called by name. And we learn two important things about the Historical Jesus: a number people thought he was the Messiah and he had brother named James. These points are spoken of in Christian sources, but it is important to see that Josephus is also aware of them. [14] [15] [16]

John the Baptist

[edit]Antiquities of the Jews, Book 18, Chapter 5

| “ | Some of the Jews believed that the destruction of Herod's army was punishment from God for killing John (called the Baptist). It seemed well deserved for he was a good man... Herod feared the growing influence John had over the people would lead to rebellion. Therefore Herod thought it best to execute John before it was too late. Accordingly he was put to death at Macherus, (the castle I before mentioned). Thus, the Jews believed that the destruction of the army was sent as a punishment upon Herod as a mark of God's displeasure. | ” |

Josephus refers to the imprisonment and death of John the Baptist by order of Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee and Perea. The context of this reference is the 36 CE defeat of King Herod, which the Jews of the time attributed to misfortune brought about by Herod's unjust execution of John. This reference is widely seen by scholars as confirming the historicity of the baptisms that John performed and coheres with what the New Testament says about John the Baptist. [17]

Testimonium Flavianum

[edit]Antiquities of the Jews, Book 18, Chapter 3

| “ | At this time there appeared Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one should call him a man. For he was a doer of doer of amazing deeds, a teacher of people who receive the truth with pleasure. And he gained a following both among many Jews and among many of Greek origin. He was the Messiah. And when Pilate, because of an accusation made by the leading men among us, condemned him to the cross, those who had loved him previously did not cease to do so. For he appeared to them on the third day, living again. The divine prophets had spoken of this and countless other wonderous things about him. And up until this very day the tribe of Christians, named after him, has not died out. | ” |

This quotation of Josephus, translated into English by Bart Ehrman, is known as the Testimonium Flavianum (meaning the testimony of Flavius Josephus) and it is found in the best manuscripts of the Antiquities. This long reference to Jesus is extremely important for it shows that by the year 93 - during the sixty or so years from the traditional date of Jesus's death - a Jewish historian of Palestine had acquired solid historical information about Jesus of Nazareth. [18]

Josephus describes Jesus as "a doer of amazing deeds" and "a teacher of people." However, what is more important to scholars is that Josephus says the "leading men among us" accused Jesus and that as a result Pilate condemned him to the cross. Elsewhere in the Antiquities, Josephus refers to " leading men" as the ruling priests. Therefore Josephus provides, in bare outline, the same sequence as we have it in the Gospels. [19]

Josephus would have derived his information while he lived in Jerusalem and Galilee where the Oral Gospel Tradition was in wide circulation. There is nothing to suggest that Josephus had actually read the Gospels or examined Roman records (of which there were none). There was,however, a developed oral tradition in First Century Palestine that could be traced to Jesus himself. [20] [21]

The Testimonium is the most discussed passage in Josephus. Of the three passages found in Josephus' Antiquities, this passage, if authentic, would offer the most direct support for the crucifixion of Jesus. [22] [23]

Part II: Authenticity

[edit]Modern scholarship has almost universally acknowledged the authenticity of the references to James the brother of Jesus and John the Baptist. [24] [25] Today the scholarly focus is on the Testimonium Flavianum. The debate centers around Textual criticism (sometimes still referred to as "lower criticism"). This is the study or examination of the text itself to identify its provenance or to trace its history. It takes as its basis, the fact that errors inevitably crept into texts as generations of scribes reproduced each other's manuscripts by hand.

Josephus had access to many scribes. As they copied the Antiquities of the Jews they made mistakes; some scribes may have added clarifications called interpolations. The copies of these copies also had the same mistakes or interpolations. As scribes introduced deviations into their copies, a ripple effect would result: copies of their copies would pass on these discrepancies as well as new ones. Scholars note these mistakes or interpolations tend to form "families" of manuscripts.

Manuscripts can be compared and arranged into "textual clusters" based on similarity of "mistakes or interpolations". Textual criticism studies the differences between these families to piece together a good idea of what the original looked like. The more surviving copies, the more accurately scholars can deduce information about the original text. [26] Today, textual critics and historians remain divided as the Testimonium Flavianum controversy continues. [27]

Traditional position

[edit]On one extreme is the traditional position, which maintains that the material about Jesus in the Testimonium Flavianum is authentic in its entirety. The arguments in favor of authenticity are as follows:

- Support for the authenticity of the Testimonium is found in an analysis of its vocabulary and style which is consistent with other parts of Josephus. [28] [29]

- The Testimonium lays primary guilt for the crucifixion on the Romans rather than the Jewish authorities. This is very different from the way early Christians wrote of the death of Jesus. It was common for Christian writers to blame the Jews for the Crucifixion. [30] [31]

- The description of Jesus as "a wise man" is not typically Christian, but is used by Josephus when describing Daniel and Solomon. [32] [33]

- Likewise early Christians did not refer to the miracles of Jesus as "paradoxa erga" (amazing or astonishing deeds) the same wording used by Josephus for the miracles of Elisha.[34] [35]

- The description of Christians as a “tribe” occurs nowhere in Christian literature, while Josephus uses the word for national or communal groups as well as the the Jewish “race”. [36] [37]

Furthermore it can be fairly said that there is no evidence against the passage on the ground of Textual criticism; the manuscript evidence is as substantial as it is for anything else in Josephus. [38]

Also the scholarship of William Whiston, remains influential in what continues to be the best-selling English work on Josephus. Although, a minority view, it is supported by such notable historians as Adolf von Harnack, who argued every word of the entire passage was authentic. The passage would make perfect sense, if Josephus were an early Jewish-Christian Ebionite. Indeed, Whiston pointed out that it is not just the passage but the entire book that reflects an Ebionite authorship. This would explain why notable Gentile leaders such as Peter (the first Bishop of Rome) and Paul (Apostle to the Gentiles) were omitted from the works of Josephus while priority was given to Jewish Christians such as James the Just and John the Baptist. Finally if Josephus was a Ebionite Christian, it would explain why the Jewish Comunnity rejected his works.[39] [40] [41]

Mythicist position

[edit]On the other extreme are the mythicists. They totally repudiate the Traditional position positing that modern criticism comes down in favor of interpolation and maintain the entire passage was made up by a Christian author and was inserted into the writings of Josephus. [42] [43] Their arguments against authenticity are as follows:

- This Testimonium is clearly not authentic because it makes the claim that "He [Jesus] was the Messiah." A Jewish historian would never make such a claim. Nor does it fit easily into the context of Book 18 of the Antiquities. [44] [45]

- More striking is the fact that no Christian authors appear to have written of this passage until the Church Father Eusebius in the year 323. Since no Christians wrote of the Testimonium, in the second and third centuries it must be an interpolation and not authentic. [46] [47]

- Mythicists also object to the wording. Josephus would not call Jesus “wise” nor would he say he taught the “truth.” Jews would never write about Jesus in such a fashion. [48] [49]

These three arguments, then, are the basis for the complete rejection of this passage. [50] [51]

Mainline

[edit]Most mainline scholarship tends to fall between these two extremes. To maintain every word of the passage is exactly as Josephus wrote is not supported by textual criticism. Mistakes and alterations crept into all texts of that time period. By the same token, the mythicist position is equally untenable. [52]

Textual critics note a scribe changing "He was called the Messiah" to "He was the Messiah" is the type of alteration they have witnessed in other ancient texts. Josephus, even if he were an Ebionite, would probably not make such a biased statement in what was supposed to be an "objective" work. Clearly, the "Traditional position" is not strong. However, recent scholarship has been even more severe on Mythicists. Leading British scholar Maurice Casey (2014) states that mythicists "cannot cope with the evidence as it stands, and constantly seek to alter it by positing interpolations." [53] Often they show no sign of any significant knowledge of Aramaic, nor demonstrate a convincing grasp of critical scholarship. Casey even questions their 'claim' to be scholars! Leading American scholar Bart Ehrman (2012), points out that as a historian "evidence matters." He goes on to say "that mythicists as a group, and as individuals, are not taken seriously by the vast majority of scholars in the fields of New Testament, early Christianity, ancient history, and theology." [54]

Conclusion

[edit]The sections on John the Baptist and James are generally considered authentic. The Testimonium Flavianum is now an area of intense scholarly activity [55] [56] [57] marked by a renaissance of Josephus studies that will likely continue well into the 21st Century. [58]

References

[edit]- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist? HarperCollins, 2012. pp 57-59

- ^ New Catholic encyclopedia, Volume 7, Edition 2, Thomson/Gale Pub, 2003. pp 1047-1048

- ^ Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. pp 120-121

- ^ John Painter, Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition, Univ of South Carolina Press, 2004. p 204

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 2014. Online

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 81-82

- ^ Antone Minard & Leslie Houlden, Jesus in History, Legend, Scripture and Tradition: A World Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2015. Volume 1, p 291-293

- ^ Craig A. Evans, The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus, Routledge, 2014. p 605

- ^ Craig A. Evans (ed), Encyclopedia of the historical Jesus, Routledge Pub, 2008. pp 605-606

- ^ Brad E. Kelle & Frank Ritchel Ames, Writing and Reading War: Rhetoric, Gender, and Ethics in Biblical and Modern Contexts, Vol 42, Society of Biblical Literature symposium series, Society of Biblical Lit. Pub, 2008. p 191-192

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 82

- ^ New Catholic encyclopedia, Volume 7, Edition 2, Thomson/Gale Pub, 2003. p 1048

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 57

- ^ Also much of what is said in this passage is recorded by the chronicler Hegesippus

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 59

- ^ John Painter, Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition, Univ of South Carolina Press, 2004. p 134

- ^ Craig A. Evans, Fabricating Jesus: How Modern Scholars Distort the Gospels, InterVarsity Press, 2008. pp 161-163

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. pp 59- 65

- ^ Craig A. Evans, Fabricating Jesus: How Modern Scholars Distort the Gospels, InterVarsity Press, 2008. p 176

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. pp 59- 65

- ^ Γίνεται δὲ κατὰ τοῦτον τὸν χρόνον Ἰησοῦς σοφὸς ἀνήρ, εἴγε ἄνδρα αὐτὸν λέγειν χρή: ἦν γὰρ παραδόξων ἔργων ποιητής, διδάσκαλος ἀνθρώπων τῶν ἡδονῇ τἀληθῆ δεχομένων, καὶ πολλοὺς μὲν Ἰουδαίους, πολλοὺς δὲ καὶ τοῦ Ἑλληνικοῦ ἐπηγάγετο: ὁ χριστὸς οὗτος ἦν. καὶ αὐτὸν ἐνδείξει τῶν πρώτων ἀνδρῶν παρ᾽ ἡμῖν σταυρῷ ἐπιτετιμηκότος Πιλάτου οὐκ ἐπαύσαντο οἱ τὸ πρῶτον ἀγαπήσαντες: ἐφάνη γὰρ αὐτοῖς τρίτην ἔχων ἡμέραν πάλιν ζῶν τῶν θείων προφητῶν ταῦτά τε καὶ ἄλλα μυρία περὶ αὐτοῦ θαυμάσια εἰρηκότων. εἰς ἔτι τε νῦν τῶν Χριστιανῶν ἀπὸ τοῦδε ὠνομασμένον οὐκ ἐπέλιπε τὸ φῦλον.[1] About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one ought to call him a man. For he was one who performed surprising deeds and was a teacher of such people as accept the truth gladly. He won over many Jews and many of the Greeks. He was the Messiah. And when, upon the accusation of the principal men among us, Pilate had condemned him to a cross, those who had first come to love him did not cease. He appeared to them spending a third day restored to life, for the prophets of God had foretold these things and a thousand other marvels about him. And the tribe of the Christians, so called after him, has still to this day not disappeared. (Based on the translation of Louis H. Feldman, The Loeb Classical Library.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, Fabricating Jesus: How Modern Scholars Distort the Gospels, InterVarsity Press, 2008. p 176

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. pp 59- 65

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 83

- ^ A few scholars have questioned the passage, contending that the absence of Christian tampering or interpolation does not itself prove authenticity.

- ^ Paul D. Wegner, A Student's Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible, InterVarsity Press, 2006. p 83

- ^ Joel B. Green & Max Turner, Jesus of Nazareth Lord and Christ: Essays on the Historical Jesus, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1994. p 95

- ^ Craig A. Evans, The Historical Jesus, Volumne 4, Taylor & Francis Pub, 2004. p 391

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p

- ^ Craig A. Evans, The Historical Jesus, Volumne 4, Taylor & Francis Pub, 2004. p 391

- ^ Jörg Frey & Jens Schröter, Jesus in apokryphen Evangelienüberlieferungen, Volume 254 of Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, Mohr Siebeck Pub, 2010. p

- ^ Josh McDowell & Bill Wilson, Evidence for the Historical Jesus, Harvest House Publishers, 2011. p 38

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 89

- ^ Josh McDowell & Bill Wilson, Evidence for the Historical Jesus, Harvest House Publishers, 2011. p 38

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 89

- ^ Josh McDowell & Bill Wilson, Evidence for the Historical Jesus, Harvest House Publishers, 2011. p 38

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 90

- ^ F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003. p 112

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 89

- ^ William Whiston,The Works of Flavius Josephus, Vol 2, J.B. Smith Pub, 1858. p 461

- ^ William Whiston, The Complete Works of Flavius Josephus Start Classics, 2014. p 89

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 61

- ^ Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account, Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. p 10

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 91

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. pp 59-60

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 91

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 62

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 92

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 63

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 92

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 63

- ^ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000. p 93

- ^ Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. p. 10

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, HarperCollins, 2012. p 20

- ^ Craig A. Evans (ed), Encyclopedia of the historical Jesus, Routledge Pub, 2008. pp 605-606

- ^ Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. p. 10 ff

- ^ F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003. p 112

- ^ New Catholic encyclopedia, Volume 7, Edition 2, Thomson/Gale Pub, 2003. p 1050