User:PolSciMe/sandbox

| This page is written in American English, which has its own spelling conventions (color, defense, traveled) and some terms that are used in it may be different or absent from other varieties of English. According to the relevant style guide, this should not be changed without broad consensus. |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

Lateralism , An economic and political system which is designed to provide the foundation for all citizens to be able to provide for themselves even if the citizen begins life in poverty. The lateral in the name is a reference to the way citizens would branch off from the basic citizen dividend. The concept of the citizen dividend is that all voting age citizens, not yet retired will be given a set amount of money. They will receive this money if they work or not, but it replaces all forms of government welfare. The idea behind this is it allows the citizen to find basic employment in a field in order to build up skills so that they can better themselves. At the same time, they are able to branch out to other endeavors as well. This is where the name of the system is derived. Lateral can be used to describe the branching of a tree. In this analogy, the citizen dividend is the roots or foundation and as the citizen uses their dividend to augment their income, they are able to branch out to other areas. The key to the citizen’s dividend being a positive influence on society is that the dividend is only a little above half the national poverty level. It provides a person enough money to work a part-time job and still have the basic needs but not enough to forgo any employment. The intent here should be obvious, it is a self-regulating social net, which will not grow or shrink in relation to the value of the nation’s currency or the voting promises of immoral politicians. This is but one of many built in corruption preventive measures in the political system.

The economic system is characterized by the aspect that trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state. In this system, the economic end goal is for all means of production to be an employee owned business which is not listed on public stock markets and only carry debt through foundation banks. Foundation banks are banks that are operated for the purpose of arranging for employee buyout of business and share a mutual contract with the employee-owned business to work under designed conditions that allow for the continuance of loans for the intent of bringing more business under employee ownership.

The entire political, economic system is fairly complicated with many concepts interwoven with the end result being a universal system designed to help all citizens better themselves to achieve financial success and self-achievement. The system is designed in a way, as to greatly reduce the chances of institutional racism, glass ceilings, and income disparity. It is widely viewed as a modern answer to the need for a compromise between liberal and conservative ideals and between socialist and capitalist systems.

The entire system is dependent on pillars are known as the essentials, and for it to work correctly each essential must be active

Characteristics

[edit]The

While representative democracy is sometimes equated with the republican form of government, the term "republic" classically has encompassed both democracies and aristocracies.[1][2] Many democracies are constitutional monarchies, such as the United Kingdom.

History

[edit]

Measurement of democracy

[edit]

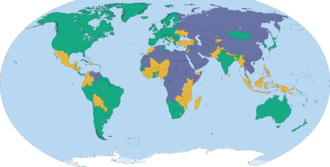

Several freedom indices are published by several organisations according to their own various definitions of the term:

- Freedom in the World published each year since 1972 by the U.S.-based Freedom House ranks countries by political rights and civil liberties that are derived in large measure from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Countries are assessed as free, partly free, or unfree.[4]

- Worldwide Press Freedom Index is published each year since 2002 (except that 2011 was combined with 2012) by France-based Reporters Without Borders. Countries are assessed as having a good situation, a satisfactory situation, noticeable problems, a difficult situation, or a very serious situation.[5]

- The Index of Freedom in the World is an index measuring classical civil liberties published by Canada's Fraser Institute, Germany's Liberales Institute, and the U.S. Cato Institute.[6] It is not currently included in the table below.

- The CIRI Human Rights Data Project measures a range of human, civil, women's and workers rights.[7] It is now hosted by the University of Connecticut. It was created in 1994.[8] In its 2011 report, the U.S. was ranked 38th in overall human rights.[9]

- The Democracy Index, published by the U.K.-based Economist Intelligence Unit, is an assessment of countries' democracy. Countries are rated to be either Full Democracies, Flawed Democracies, Hybrid Regimes, or Authoritarian regimes. Full democracies, flawed democracies, and hybrid regimes are considered to be democracies, and the authoritarian nations are considered to be dictatorial. The index is based on 60 indicators grouped in five different categories.[10]

- The U.S.-based Polity data series is a widely used data series in political science research. It contains coded annual information on regime authority characteristics and transitions for all independent states with greater than 500,000 total population and covers the years 1800–2006. Polity's conclusions about a state's level of democracy are based on an evaluation of that state's elections for competitiveness, openness and level of participation. Data from this series is not currently included in the table below. The Polity work is sponsored by the Political Instability Task Force (PITF) which is funded by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. However, the views expressed in the reports are the authors' alone and do not represent the views of the US Government.

- MaxRange, a dataset defining level of democracy and institutional structure(regime-type) on a 100-graded scale where every value represents a unique regime type. Values are sorted from 1-100 based on level of democracy and political accountability. MaxRange defines the value corresponding to all states and every month from 1789 to 2015 and updating. MaxRange is created and developed by Max Range, and is now associated with the university of Halmstad, Sweden.[11]

Types of governmental democracies

[edit]Democracy has taken a number of forms, both in theory and practice. Some varieties of democracy provide better representation and more freedom for their citizens than others.[12][13] However, if any democracy is not structured so as to prohibit the government from excluding the people from the legislative process, or any branch of government from altering the separation of powers in its own favour, then a branch of the system can accumulate too much power and destroy the democracy.[14][15][16]

|

The following kinds of democracy are not exclusive of one another: many specify details of aspects that are independent of one another and can co-exist in a single system.

Basic forms

[edit]Several variants of democracy exist, but there are two basic forms, both of which concern how the whole body of all eligible citizens executes its will. One form of democracy is direct democracy, in which all eligible citizens have active participation in the political decision making, for example voting on policy initiatives directly.[17] In most modern democracies, the whole body of eligible citizens remain the sovereign power but political power is exercised indirectly through elected representatives; this is called a representative democracy.

Direct

[edit]

Direct democracy is a political system where the citizens participate in the decision-making personally, contrary to relying on intermediaries or representatives. The use of a lot system, a characteristic of Athenian democracy, is unique to direct democracies. In this system, important governmental and administrative tasks are performed by citizens picked from a lottery.[18] A direct democracy gives the voting population the power to:

- Change constitutional laws,

- Put forth initiatives, referendums and suggestions for laws,

- Give binding orders to elective officials, such as revoking them before the end of their elected term, or initiating a lawsuit for breaking a campaign promise.

Within modern-day representative governments, certain electoral tools like referendums, citizens' initiatives and recall elections are referred to as forms of direct democracy.[19] Direct democracy as a government system currently exists in the Swiss cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus,[20] and kurdish cantons of Rojava.[21]

Representative

[edit]Representative democracy involves the election of government officials by the people being represented. If the head of state is also democratically elected then it is called a democratic republic.[22] The most common mechanisms involve election of the candidate with a majority or a plurality of the votes. Most western countries have representative systems.[20]

Representatives may be elected or become diplomatic representatives by a particular district (or constituency), or represent the entire electorate through proportional systems, with some using a combination of the two. Some representative democracies also incorporate elements of direct democracy, such as referendums. A characteristic of representative democracy is that while the representatives are elected by the people to act in the people's interest, they retain the freedom to exercise their own judgement as how best to do so. Such reasons have driven criticism upon representative democracy,[23][24] pointing out the contradictions of representation mechanisms' with democracy[25][26]

Parliamentary

[edit]Parliamentary democracy is a representative democracy where government is appointed by, or can be dismissed by, representatives as opposed to a "presidential rule" wherein the president is both head of state and the head of government and is elected by the voters. Under a parliamentary democracy, government is exercised by delegation to an executive ministry and subject to ongoing review, checks and balances by the legislative parliament elected by the people.[27][28][29][30]

Parliamentary systems have the right to dismiss a Prime Minister at any point in time that they feel he or she is not doing their job to the expectations of the legislature. This is done through a Vote of No Confidence where the legislature decides whether or not to remove the Prime Minister from office by a majority support for his or her dismissal.[31] In some countries, the Prime Minister can also call an election whenever he or she so chooses, and typically the Prime Minister will hold an election when he or she knows that they are in good favour with the public as to get re-elected. In other parliamentary democracies extra elections are virtually never held, a minority government being preferred until the next ordinary elections. An important feature of the parliamentary democracy is the concept of the "loyal opposition". The essence of the concept is that the second largest political party (or coalition) opposes the governing party (or coalition), while still remaining loyal to the state and its democratic principles.

Presidential

[edit]Presidential Democracy is a system where the public elects the president through free and fair elections. The president serves as both the head of state and head of government controlling most of the executive powers. The president serves for a specific term and cannot exceed that amount of time. Elections typically have a fixed date and aren't easily changed. The president has direct control over the cabinet, specifically appointing the cabinet members.[31]

The president cannot be easily removed from office by the legislature, but he or she cannot remove members of the legislative branch any more easily. This provides some measure of separation of powers. In consequence however, the president and the legislature may end up in the control of separate parties, allowing one to block the other and thereby interfere with the orderly operation of the state. This may be the reason why presidential democracy is not very common outside the Americas, Africa, and Central and Southeast Asia.[31]

A semi-presidential system is a system of democracy in which the government includes both a prime minister and a president. The particular powers held by the prime minister and president vary by country.[31]

Hybrid or semi-direct

[edit]Some modern democracies that are predominantly representative in nature also heavily rely upon forms of political action that are directly democratic. These democracies, which combine elements of representative democracy and direct democracy, are termed hybrid democracies,[32] semi-direct democracies or participatory democracies. Examples include Switzerland and some U.S. states, where frequent use is made of referendums and initiatives.

The Swiss confederation is a semi-direct democracy.[20] At the federal level, citizens can propose changes to the constitution (federal popular initiative) or ask for a referendum to be held on any law voted by the parliament.[20] Between January 1995 and June 2005, Swiss citizens voted 31 times, to answer 103 questions (during the same period, French citizens participated in only two referendums).[20] Although in the past 120 years less than 250 initiatives have been put to referendum. The populace has been conservative, approving only about 10% of the initiatives put before them; in addition, they have often opted for a version of the initiative rewritten by government.[citation needed]

In the United States, no mechanisms of direct democracy exists at the federal level, but over half of the states and many localities provide for citizen-sponsored ballot initiatives (also called "ballot measures", "ballot questions" or "propositions"), and the vast majority of states allow for referendums. Examples include the extensive use of referendums in the US state of California, which is a state that has more than 20 million voters.[33]

In New England, Town meetings are often used, especially in rural areas, to manage local government. This creates a hybrid form of government, with a local direct democracy and a state government which is representative. For example, most Vermont towns hold annual town meetings in March in which town officers are elected, budgets for the town and schools are voted on, and citizens have the opportunity to speak and be heard on political matters.[34]

Variants

[edit]Constitutional monarchy

[edit]

Many countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavian countries, Thailand, Japan and Bhutan turned powerful monarchs into constitutional monarchs with limited or, often gradually, merely symbolic roles. For example, in the predecessor states to the United Kingdom, constitutional monarchy began to emerge and has continued uninterrupted since the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and passage of the Bill of Rights 1689.[35][36]

In other countries, the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system (as in France, China, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece and Egypt). An elected president, with or without significant powers, became the head of state in these countries.

Elite upper houses of legislatures, which often had lifetime or hereditary tenure, were common in many nations. Over time, these either had their powers limited (as with the British House of Lords) or else became elective and remained powerful (as with the Australian Senate).

Republic

[edit]The term republic has many different meanings, but today often refers to a representative democracy with an elected head of state, such as a president, serving for a limited term, in contrast to states with a hereditary monarch as a head of state, even if these states also are representative democracies with an elected or appointed head of government such as a prime minister.[37]

The Founding Fathers of the United States rarely praised and often criticised democracy, which in their time tended to specifically mean direct democracy, often without the protection of a constitution enshrining basic rights; James Madison argued, especially in The Federalist No. 10, that what distinguished a democracy from a republic was that the former became weaker as it got larger and suffered more violently from the effects of faction, whereas a republic could get stronger as it got larger and combats faction by its very structure.

What was critical to American values, John Adams insisted,[38] was that the government be "bound by fixed laws, which the people have a voice in making, and a right to defend." As Benjamin Franklin was exiting after writing the U.S. constitution, a woman asked him "Well, Doctor, what have we got—a republic or a monarchy?". He replied "A republic—if you can keep it."[39]

Liberal democracy

[edit]A liberal democracy is a representative democracy in which the ability of the elected representatives to exercise decision-making power is subject to the rule of law, and moderated by a constitution or laws that emphasise the protection of the rights and freedoms of individuals, and which places constraints on the leaders and on the extent to which the will of the majority can be exercised against the rights of minorities (see civil liberties).

In a liberal democracy, it is possible for some large-scale decisions to emerge from the many individual decisions that citizens are free to make. In other words, citizens can "vote with their feet" or "vote with their dollars", resulting in significant informal government-by-the-masses that exercises many "powers" associated with formal government elsewhere.

Socialist

[edit]Socialist thought has several different views on democracy. Social democracy, democratic socialism, and the dictatorship of the proletariat (usually exercised through Soviet democracy) are some examples. Many democratic socialists and social democrats believe in a form of participatory, industrial, economic and/or workplace democracy combined with a representative democracy.

Within Marxist orthodoxy there is a hostility to what is commonly called "liberal democracy", which they simply refer to as parliamentary democracy because of its often centralised nature. Because of their desire to eliminate the political elitism they see in capitalism, Marxists, Leninists and Trotskyists believe in direct democracy implemented through a system of communes (which are sometimes called soviets). This system ultimately manifests itself as council democracy and begins with workplace democracy. (See Democracy in Marxism.)

Democracy cannot consist solely of elections that are nearly always fictitious and managed by rich landowners and professional politicians.

— Che Guevara, Speech, Uruguay, 1961[40]

Anarchist

[edit]Anarchists are split in this domain, depending on whether they believe that a majority-rule is tyrannic or not. The only form of democracy considered acceptable to many anarchists is direct democracy. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that the only acceptable form of direct democracy is one in which it is recognised that majority decisions are not binding on the minority, even when unanimous.[41] However, anarcho-communist Murray Bookchin criticised individualist anarchists for opposing democracy,[42] and says "majority rule" is consistent with anarchism.[43]

Some anarcho-communists oppose the majoritarian nature of direct democracy, feeling that it can impede individual liberty and opt in favour of a non-majoritarian form of consensus democracy, similar to Proudhon's position on direct democracy.[44] Henry David Thoreau, who did not self-identify as an anarchist but argued for "a better government"[45] and is cited as an inspiration by some anarchists, argued that people should not be in the position of ruling others or being ruled when there is no consent.

Anarcho-capitalists, voluntaryists and other right-anarchists oppose institutional democracy as they consider it in conflict with widely held moral values and ethical principles and their conception of individual rights. The a priori Rothbardian argument is that the state is a coercive institution which necessarily violates the non-aggression principle (NAP). Some right-anarchists also criticise democracy on a posteriori consequentialist grounds, in terms of inefficiency or disability in bringing about maximisation of individual liberty. They maintain the people who participate in democratic institutions are foremost driven by economic self-interest.[46][47]

Sortition

[edit]Sometimes called "democracy without elections", sortition chooses decision makers via a random process. The intention is that those chosen will be representative of the opinions and interests of the people at large, and be more fair and impartial than an elected official. The technique was in widespread use in Athenian Democracy and Renaissance Florence[48] and is still used in modern jury selection.

Consociational

[edit]A consociational democracy allows for simultaneous majority votes in two or more ethno-religious constituencies, and policies are enacted only if they gain majority support from both or all of them.

Consensus democracy

[edit]A consensus democracy, in contrast, would not be dichotomous. Instead, decisions would be based on a multi-option approach, and policies would be enacted if they gained sufficient support, either in a purely verbal agreement, or via a consensus vote—a multi-option preference vote. If the threshold of support were at a sufficiently high level, minorities would be as it were protected automatically. Furthermore, any voting would be ethno-colour blind.

Supranational

[edit]Qualified majority voting is designed by the Treaty of Rome to be the principal method of reaching decisions in the European Council of Ministers. This system allocates votes to member states in part according to their population, but heavily weighted in favour of the smaller states. This might be seen as a form of representative democracy, but representatives to the Council might be appointed rather than directly elected.

Inclusive

[edit]| Youth rights |

|---|

Inclusive democracy is a political theory and political project that aims for direct democracy in all fields of social life: political democracy in the form of face-to-face assemblies which are confederated, economic democracy in a stateless, moneyless and marketless economy, democracy in the social realm, i.e. self-management in places of work and education, and ecological democracy which aims to reintegrate society and nature. The theoretical project of inclusive democracy emerged from the work of political philosopher Takis Fotopoulos in "Towards An Inclusive Democracy" and was further developed in the journal Democracy & Nature and its successor The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy.

The basic unit of decision making in an inclusive democracy is the demotic assembly, i.e. the assembly of demos, the citizen body in a given geographical area which may encompass a town and the surrounding villages, or even neighbourhoods of large cities. An inclusive democracy today can only take the form of a confederal democracy that is based on a network of administrative councils whose members or delegates are elected from popular face-to-face democratic assemblies in the various demoi. Thus, their role is purely administrative and practical, not one of policy-making like that of representatives in representative democracy.

The citizen body is advised by experts but it is the citizen body which functions as the ultimate decision-taker . Authority can be delegated to a segment of the citizen body to carry out specific duties, for example to serve as members of popular courts, or of regional and confederal councils. Such delegation is made, in principle, by lot, on a rotation basis, and is always recallable by the citizen body. Delegates to regional and confederal bodies should have specific mandates.

Participatory politics

[edit]A Parpolity or Participatory Polity is a theoretical form of democracy that is ruled by a Nested Council structure. The guiding philosophy is that people should have decision making power in proportion to how much they are affected by the decision. Local councils of 25–50 people are completely autonomous on issues that affect only them, and these councils send delegates to higher level councils who are again autonomous regarding issues that affect only the population affected by that council.

A council court of randomly chosen citizens serves as a check on the tyranny of the majority, and rules on which body gets to vote on which issue. Delegates may vote differently from how their sending council might wish, but are mandated to communicate the wishes of their sending council. Delegates are recallable at any time. Referendums are possible at any time via votes of most lower-level councils, however, not everything is a referendum as this is most likely a waste of time. A parpolity is meant to work in tandem with a participatory economy.

Cosmopolitan

[edit]Cosmopolitan democracy, also known as Global democracy or World Federalism, is a political system in which democracy is implemented on a global scale, either directly or through representatives. An important justification for this kind of system is that the decisions made in national or regional democracies often affect people outside the constituency who, by definition, cannot vote. By contrast, in a cosmopolitan democracy, the people who are affected by decisions also have a say in them.[49]

According to its supporters, any attempt to solve global problems is undemocratic without some form of cosmopolitan democracy. The general principle of cosmopolitan democracy is to expand some or all of the values and norms of democracy, including the rule of law; the non-violent resolution of conflicts; and equality among citizens, beyond the limits of the state. To be fully implemented, this would require reforming existing international organisations, e.g. the United Nations, as well as the creation of new institutions such as a World Parliament, which ideally would enhance public control over, and accountability in, international politics.

Cosmopolitan Democracy has been promoted, among others, by physicist Albert Einstein,[50] writer Kurt Vonnegut, columnist George Monbiot, and professors David Held and Daniele Archibugi.[51] The creation of the International Criminal Court in 2003 was seen as a major step forward by many supporters of this type of cosmopolitan democracy.

Creative democracy

[edit]Creative Democracy is advocated by American philosopher John Dewey. The main idea about Creative Democracy is that democracy encourages individual capacity building and the interaction among the society. Dewey argues that democracy is a way of life in his work of "Creative Democracy: The Task Before Us" [52] and an experience built on faith in human nature, faith in human beings, and faith in working with others. Democracy, in Dewey's view, is a moral ideal requiring actual effort and work by people; it is not an institutional concept that exists outside of ourselves. "The task of democracy", Dewey concludes, "is forever that of creation of a freer and more humane experience in which all share and to which all contribute".

Guided democracy

[edit]Guided democracy is a form of democracy which incorporates regular popular elections, but which often carefully "guides" the choices offered to the electorate in a manner which may reduce the ability of the electorate to truly determine the type of government exercised over them. Such democracies typically have only one central authority which is often not subject to meaningful public review by any other governmental authority. Russian-style democracy has often been referred to as a "Guided democracy."[53] Russian politicians have referred to their government as having only one center of power/ authority, as opposed to most other forms of democracy which usually attempt to incorporate two or more naturally competing sources of authority within the same government.[54]

Non-governmental democracy

[edit]Aside from the public sphere, similar democratic principles and mechanisms of voting and representation have been used to govern other kinds of groups. Many non-governmental organisations decide policy and leadership by voting. Most trade unions and cooperatives are governed by democratic elections. Corporations are controlled by shareholders on the principle of one share, one vote. An analogous system, that fuses elements of democracy with sharia law, has been termed islamocracy.[55]

Theory

[edit]

Aristotle

[edit]Aristotle contrasted rule by the many (democracy/polity), with rule by the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), and with rule by a single person (tyranny or today autocracy/absolute monarchy). He also thought that there was a good and a bad variant of each system (he considered democracy to be the degenerate counterpart to polity).[56][57]

For Aristotle the underlying principle of democracy is freedom, since only in a democracy the citizens can have a share in freedom. In essence, he argues that this is what every democracy should make its aim. There are two main aspects of freedom: being ruled and ruling in turn, since everyone is equal according to number, not merit, and to be able to live as one pleases.

But one factor of liberty is to govern and be governed in turn; for the popular principle of justice is to have equality according to number, not worth, ... And one is for a man to live as he likes; for they say that this is the function of liberty, inasmuch as to live not as one likes is the life of a man that is a slave.

Early Republican theory

[edit]A common view among early and renaissance Republican theorists was that democracy could only survive in small political communities.[58] Heeding the lessons of the Roman Republic's shift to monarchism as it grew larger, these Republican theorists held that the expansion of territory and population inevitably led to tyranny.[58] Democracy was therefore highly fragile and rare historically, as it could only survive in small political units, which due to their size were vulnerable to conquest by larger political units.[58] Montesquieu famously said, "if a republic is small, it is destroyed by an outside force; if it is large, it is destroyed by an internal vice."[58] Rousseau asserted, "It is, therefore the natural property of small states to be governed as a republic, of middling ones to be subject to a monarch, and of large empires to be swayed by a despotic prince."[58]

Rationale

[edit]Among modern political theorists, there are three contending conceptions of the fundamental rationale for democracy: aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy, and radical democracy.[59]

Aggregative

[edit]The theory of aggregative democracy claims that the aim of the democratic processes is to solicit citizens' preferences and aggregate them together to determine what social policies society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented.

Different variants of aggregative democracy exist. Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens have given teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not "rule" because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.[60] Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner.

According to the theory of direct democracy, on the other hand, citizens should vote directly, not through their representatives, on legislative proposals. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socialises and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not really rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies.

Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter—with half to their left and the other half to their right. This is not actually a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes. Anthony Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments. Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[61]

Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision). He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation.[62] Similarly, Ronald Dworkin argues that "democracy is a substantive, not a merely procedural, ideal."[63]

Deliberative

[edit]Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by deliberation. Unlike aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy holds that, for a democratic decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation, not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting. Authentic deliberation is deliberation among decision-makers that is free from distortions of unequal political power, such as power a decision-maker obtained through economic wealth or the support of interest groups.[64][65][66] If the decision-makers cannot reach consensus after authentically deliberating on a proposal, then they vote on the proposal using a form of majority rule. Many theorists is discussing the conception of Debliberative Democracy, considering specially the thought of Jürgen Habermas.

Radical

[edit]Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy's role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision making processes.

Criticism

[edit]

Inefficiencies

[edit]Some economists have criticized the efficiency of democracy, citing the premise of the irrational voter, or a voter who makes decisions without all of the facts or necessary information in order to make a truly informed decision. Another argument is that democracy slows down processes because of the amount of input and participation needed in order to go forward with a decision. A common example often quoted to substantiate this point is the high economic development achieved by China (a non-democratic country) as compared to India (a democratic country). According to economists, the lack of democratic participation in countries like China allows for unfettered economic growth.[67]

Popular rule as a façade

[edit]The 20th-century Italian thinkers Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca (independently) argued that democracy was illusory, and served only to mask the reality of elite rule. Indeed, they argued that elite oligarchy is the unbendable law of human nature, due largely to the apathy and division of the masses (as opposed to the drive, initiative and unity of the elites), and that democratic institutions would do no more than shift the exercise of power from oppression to manipulation.[68] As Louis Brandeis once professed, "We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can't have both."[69]

Between 1946 and 2000 Soviet Union/Russia and USA have intervened in at least 117 elections.[70]

Mob rule

[edit]Plato's The Republic presents a critical view of democracy through the narration of Socrates: "Democracy, which is a charming form of government, full of variety and disorder, and dispensing a sort of equality to equals and unequaled alike."[71] In his work, Plato lists 5 forms of government from best to worst. Assuming that the Republic was intended to be a serious critique of the political thought in Athens, Plato argues that only Kallipolis, an aristocracy led by the unwilling philosopher-kings (the wisest men), is a just form of government.[72]

James Madison critiqued direct democracy (which he referred to simply as "democracy") in Federalist No. 10, arguing that representative democracy—which he described using the term "republic"—is a preferable form of government, saying: "... democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths." Madison offered that republics were superior to democracies because republics safeguarded against tyranny of the majority, stating in Federalist No. 10: "the same advantage which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic".

Political instability

[edit]More recently, democracy is criticised for not offering enough political stability. As governments are frequently elected on and off there tends to be frequent changes in the policies of democratic countries both domestically and internationally. Even if a political party maintains power, vociferous, headline grabbing protests and harsh criticism from the popular media are often enough to force sudden, unexpected political change. Frequent policy changes with regard to business and immigration are likely to deter investment and so hinder economic growth. For this reason, many people have put forward the idea that democracy is undesirable for a developing country in which economic growth and the reduction of poverty are top priorities.[73]

This opportunist alliance not only has the handicap of having to cater to too many ideologically opposing factions, but it is usually short lived since any perceived or actual imbalance in the treatment of coalition partners, or changes to leadership in the coalition partners themselves, can very easily result in the coalition partner withdrawing its support from the government.

Biased media has been accused of causing political instability, resulting in the obstruction of democracy, rather than its promotion.[74]

Fraudulent elections

[edit]In representative democracies, it may not benefit incumbents to conduct fair elections. A study showed that incumbents who rig elections stay in office 2.5 times as long as those who permit fair elections.[75] Democracies in countries with high per capita income have been found to be less prone to violence, but in countries with low incomes the tendency is the reverse.[75] Election misconduct is more likely in countries with low per capita incomes, small populations, rich in natural resources, and a lack of institutional checks and balances. Sub-Saharan countries, as well as Afghanistan, all tend to fall into that category.[75]

Governments that have frequent elections tend to have significantly more stable economic policies than those governments who have infrequent elections. However, this trend does not apply to governments where fraudulent elections are common.[75]

Opposition

[edit]Democracy in modern times has almost always faced opposition from the previously existing government, and many times it has faced opposition from social elites. The implementation of a democratic government within a non-democratic state is typically brought about by democratic revolution.

Post-Enlightenment ideologies such as fascism, nazism, and neo-fundamentalism oppose democracy on different grounds, generally citing that the concept of democracy as a constant process is flawed and detrimental to a preferable course of development.

Development

[edit]Several philosophers and researchers have outlined historical and social factors seen as supporting the evolution of democracy. Cultural factors like Protestantism influenced the development of democracy, rule of law, human rights and political liberty (the faithful elected priests, religious freedom and tolerance has been practiced).

Other commentators have mentioned the influence of wealth (e.g. S. M. Lipset, 1959). In a related theory, Ronald Inglehart suggests that improved living-standards can convince people that they can take their basic survival for granted, leading to increased emphasis on self-expression values, which is highly correlated to democracy.[76]

Carroll Quigley concludes that the characteristics of weapons are the main predictor of democracy:[77][78] Democracy tends to emerge only when the best weapons available are easy for individuals to buy and use.[79] By the 1800s, guns were the best personal weapons available, and in America, almost everyone could afford to buy a gun, and could learn how to use it fairly easily. Governments couldn't do any better: it became the age of mass armies of citizen soldiers with guns[79] Similarly, Periclean Greece was an age of the citizen soldier and democracy.[80]

Recent theories stress the relevance of education and of human capital - and within them of cognitive ability to increasing tolerance, rationality, political literacy and participation. Two effects of education and cognitive ability are distinguished: a cognitive effect (competence to make rational choices, better information-processing) and an ethical effect (support of democratic values, freedom, human rights etc.), which itself depends on intelligence.[81][82][83]

Evidence that is consistent with conventional theories of why democracy emerges and is sustained has been hard to come by. Recent statistical analyses have challenged modernisation theory by demonstrating that there is no reliable evidence for the claim that democracy is more likely to emerge when countries become wealthier, more educated, or less unequal.[84] Neither is there convincing evidence that increased reliance on oil revenues prevents democratisation, despite a vast theoretical literature on "the Resource Curse" that asserts that oil revenues sever the link between citizen taxation and government accountability, seen as the key to representative democracy.[85] The lack of evidence for these conventional theories of democratisation have led researchers to search for the "deep" determinants of contemporary political institutions, be they geographical or demographic.[86][87]

In the 21st century, democracy has become such a popular method of reaching decisions that its application beyond politics to other areas such as entertainment, food and fashion, consumerism, urban planning, education, art, literature, science and theology has been criticised as "the reigning dogma of our time".[88] The argument suggests that applying a populist or market-driven approach to art and literature (for example), means that innovative creative work goes unpublished or unproduced. In education, the argument is that essential but more difficult studies are not undertaken. Science, as a truth-based discipline, is particularly corrupted by the idea that the correct conclusion can be arrived at by popular vote. However, more recently, theorists have also advanced the concept epistemic democracy to assert that democracy actually does a good job tracking the truth.

Robert Michels asserts that although democracy can never be fully realised, democracy may be developed automatically in the act of striving for democracy: "The peasant in the fable, when on his death-bed, tells his sons that a treasure is buried in the field. After the old man's death the sons dig everywhere in order to discover the treasure. They do not find it. But their indefatigable labor improves the soil and secures for them a comparative well-being. The treasure in the fable may well symbolise democracy."[89]

Dr. Harald Wydra, in his book Communism and The Emergence of Democracy (2007), maintains that the development of democracy should not be viewed as a purely procedural or as a static concept but rather as an ongoing "process of meaning formation".[90] Drawing on Claude Lefort's idea of the empty place of power, that "power emanates from the people [...] but is the power of nobody", he remarks that democracy is reverence to a symbolic mythical authority as in reality, there is no such thing as the people or demos. Democratic political figures are not supreme rulers but rather temporary guardians of an empty place. Any claim to substance such as the collective good, the public interest or the will of the nation is subject to the competitive struggle and times of for[clarification needed] gaining the authority of office and government. The essence of the democratic system is an empty place, void of real people which can only be temporarily filled and never be appropriated. The seat of power is there, but remains open to constant change. As such, what "democracy" is or what is "democratic" progresses throughout history as a continual and potentially never ending process of social construction.[citation needed]

In 2010 a study by a German military think-tank analyzed how peak oil might change the global economy. The study raises fears for the survival of democracy itself. It suggests that parts of the population could perceive the upheaval triggered by peak oil as a general systemic crisis. This would create "room for ideological and extremist alternatives to existing forms of government".[91]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws, Bk. II, ch. 2–3.

- ^ Everdell, William R. (2000) [1983]. The end of kings: a history of republics and republicans (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226224824.

- ^ Freedom in The World 2017 - Populists and Autocrats: The Dual Threat to Global Democracy by Freedom House, January 31, 2017

- ^ a b Freedom in The World 2016 report (PDF)

- ^ "Press Freedom Index 2014", Reporters Without Borders, 11 May 2014

- ^ " World Freedom Index 2013: Canadian Fraser Institute Ranks Countries ", Ryan Craggs, Huffington Post, 14 January 2013

- ^ "CIRI Human Rights Data Project", website. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Michael Kirk (December 10, 2010). "Annual International Human Rights Ratings Announced". University of Connecticut.

- ^ "Human Rights in 2011: The CIRI Report". CIRI Human Rights Data Project. August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Democracy index 2012: Democracy at a standstill". Economist Intelligence Unit. 14 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ "MaxRange".

- ^ G. F. Gaus, C. Kukathas, Handbook of Political Theory, SAGE, 2004, pp. 143–45, ISBN 0-7619-6787-7, Google Books link

- ^ The Judge in a Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 26, ISBN 0-691-12017-X, Google Books link

- ^ A. Barak, The Judge in a Democracy, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 40, ISBN 0-691-12017-X, Google Books link

- ^ T. R. Williamson, Problems in American Democracy, Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 36, ISBN 1-4191-4316-6, Google Books link

- ^ U. K. Preuss, "Perspectives of Democracy and the Rule of Law." Journal of Law and Society, 18:3 (1991). pp. 353–64

- ^ Budge, Ian (2001). "Direct democracy". In Clarke, Paul A.B. & Foweraker, Joe (ed.). Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-19396-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Bernard Manin. Principles of Representative Government. pp. 8–11 (1997).

- ^ Beramendi, Virginia, and Jennifer Somalie. Angeyo. Direct Democracy: The International Idea Handbook. Stockholm, Sweden: International IDEA, 2008. Print.

- ^ a b c d e Vincent Golay and Mix et Remix, Swiss political institutions, Éditions loisirs et pédagogie, 2008. ISBN 978-2-606-01295-3.

- ^ "A Very Different Ideology in the Middle East". Rudaw.

- ^ "Radical Revolution - The Thermidorean Reaction". Wsu.edu. 1999-06-06. Archived from the original on 1999-02-03. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Köchler, Hans (1987). The Crisis of Representative Democracy. Frankfurt/M., Bern, New York. ISBN 978-3-8204-8843-2.

- ^ Urbinati, Nadia (October 1, 2008). "2". Representative Democracy: Principles and Genealogy. ISBN 978-0226842790.

- ^ Fenichel Pitkin, Hanna (September 2004). "Representation and democracy: uneasy alliance". Scandinavian Political Studies. 27 (3). Wiley: 335–42. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2004.00109.x.

- ^ Aristotle. "Ch. 9". Politics. Vol. Book 4.

- ^ Keen, Benjamin, A History of Latin America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph, Hawaii: A History. New York: Prentice Hall, 1948.

- ^ Brown, Charles H., The Correspondents' War. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1967.

- ^ Taussig, Capt. J. K., "Experiences during the Boxer Rebellion," in Quarterdeck and Fo'c'sle. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1963

- ^ a b c d O'Neil, Patrick H. Essentials of Comparative Politics. 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton 2010. Print

- ^ Garret, Elizabeth (October 13, 2005). "The Promise and Perils of Hybrid Democracy" (PDF). The Henry Lecture, University of Oklahoma Law School. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [permanent dead link] - ^ "Article on direct democracy by Imraan Buccus". Themercury.co.za. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "A Citizen's Guide To Vermont Town Meeting". July 2008. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Kopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark; Hanson, Stephen E., eds. (2014). Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order (4, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1139991384.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

refNARoPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Republic – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Novanglus, no. 7. 6 March 1775

- ^ "The Founders' Constitution: Volume 1, Chapter 18, Introduction, "Epilogue: Securing the Republic"". Press-pubs.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Economics Cannot be Separated from Politics" speech by Che Guevara to the ministerial meeting of the Inter-American Economic and Social Council (CIES), in Punta del Este, Uruguay on August 8, 1961

- ^ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. General Idea of the Revolution See also commentary by Graham, Robert. The General Idea of Proudhon's Revolution

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. Communalism: The Democratic Dimensions of Social Anarchism. Anarchism, Marxism and the Future of the Left: Interviews and Essays, 1993–1998, AK Press 1999, p. 155

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm

- ^ Graeber, David and Grubacic, Andrej. Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century

- ^ Thoreau, H. D. On the Duty of Civil Disobedience

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. Man, Economy and State: Chapter 5 - Binary Intervention: Government Expenditures

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. The Anatomy of the State

- ^ Dowlen, Oliver (2008). The Political Potential of Sortition: A study of the random selection of citizens for public office. Imprint Academic.

- ^ "Article on Cosmopolitan democracy by Daniele Archibugi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "letter by Einstein – "To the General Assembly of the United Nations"". Retrieved 2 July 2013., first published in United Nations World New York, Oct 1947, pp13-14

- ^ Daniele Archibugi & David Held, eds., Cosmopolitan Democracy. An Agenda for a New World Order, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1995; David Held, Democracy and the Global Order, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1995, Daniele Archibugi, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2008

- ^ http://pages.uoregon.edu/koopman/courses_readings/dewey/dewey_creative_democracy.pdf

- ^ Ten Years After the Soviet Breakup: From Democratization to "Guided Democracy" Journal of Democracy. By Archie Brown. Oct. 2001. Downloaded Apr. 28, 2017.

- ^ Putin’s Rule: Its Main Features and the Current Diarchy Johnson's Russia List. By Peter Reddaway. Feb. 18, 2009. Downloaded April 28, 2017.

- ^ Tibi, Bassam (2013). The Sharia State: Arab Spring and Democratization. p. 161.

- ^ "Aristotle, The Politics". Humanities.mq.edu.au. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Aristotle". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b c d e "Deudney, D.: Bounding Power: Republican Security Theory from the Polis to the Global Village. (eBook and Paperback)". press.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ^ Springer, Simon (2011). "Public Space as Emancipation: Meditations on Anarchism, Radical Democracy, Neoliberalism and Violence". Antipode. 43 (2): 525–62. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00827.x.

- ^ Joseph Schumpeter, (1950). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-133008-6.

- ^ Anthony Downs, (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harpercollins College. ISBN 0-06-041750-1.

- ^ Dahl, Robert, (1989). Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04938-2

- ^ Dworkin, Ronald (2006). Is Democracy Possible Here? Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691138725, p. 134.

- ^ Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson (2002). Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12019-5

- ^ Joshua Cohen, "Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy" in Essays on Reason and Politics: Deliberative Democracy Ed. James Bohman and William Rehg (The MIT Press: Cambridge) 1997, 72–73.

- ^ Ethan J. "Can Direct Democracy Be Made Deliberative?", Buffalo Law Review, Vol. 54, 2006

- ^ "Is Democracy a Pre-Condition in Economic Growth? A Perspective from the Rise of Modern China". UN Chronicle. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Femia, Joseph V. "Against the Masses", Oxford 2001

- ^ Dilliard, Iriving. "Mr. Justice Brandeis, Great American", Modern View Press 1941, p. 42. Quoting Raymond Lonergan. See, http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015009170443;seq=56;view=1up;num=42

- ^ http://www.isanet.org/Publications/ISQ/Posts/ID/5027/When-the-Great-Power-Gets-a-Vote-The-Effects-of-Great-Power-Electoral-Interventions-on-Election-Results

- ^ Plato, the Republic of Plato (London: J.M Dent & Sons LTD.; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc.), 558-C.

- ^ The contrast between Plato's theory of philosopher-kings, arresting change, and Aristotle's embrace of change, is the historical tension espoused by Karl Raimund Popper in his WWII treatise, The Open Society and its Enemies (1943).

- ^ "Head to head: African democracy". BBC News. 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ The Review of Policy Research, Volume 22, Issues 1-3, Policy Studies Organization, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. Blackwell Publishing, 2005. p. 28

- ^ a b c d Paul Collier (2009-11-08). "5 myths about the beauty of the ballot box". Washington Post. p. B2.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Inglehart, Ronald. Welzel, Christian Modernisation, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, 2005. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ Foreword, written by historian Harry J Hogan in 1982, to Quigley's Weapons Systems and Political Stability

- ^ see also Chester G Starr, Review of Weapons Systems and Political Stability, American Historical Review, Feb 1984, p98, available at carrollquigley.net

- ^ a b Carroll Quigley (1983). Weapons systems and political stability: a history. University Press of America. pp. 38–9. ISBN 978-0-8191-2947-5. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Carroll Quigley (1983). Weapons systems and political stability: a history. University Press of America. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-8191-2947-5. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Glaeser, E.; Ponzetto, G.; Shleifer, A. (2007). "Why does democracy need education?". Journal of Economic Growth. 12 (2): 77–99. doi:10.1007/s10887-007-9015-1.

- ^ Deary, I. J.; Batty, G. D.; Gale, C. R. (2008). "Bright children become enlightened adults". Psychological Science. 19 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02036.x. hdl:20.500.11820/a86dbef4-60eb-44fa-add3-513841cdf81b. PMID 18181782. S2CID 21297949.

- ^ Rindermann, H (2008). "Relevance of education and intelligence for the political development of nations: Democracy, rule of law and political liberty". Intelligence. 36 (4): 306–22. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.09.003.

- ^ Albertus, Michael; Menaldo, Victor (2012). "Coercive Capacity and the Prospects for Democratisation". Comparative Politics. 44 (2): 151–69. doi:10.5129/001041512798838003.

- ^ "The Resource Curse: Does the Emperor Have no Clothes?".

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. (2006). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge Books, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85526-6.

- ^ "Rainfall and Democracy".

- ^ Farrelly, Elizabeth (2011-09-15). "Deafened by the roar of the crowd". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ^ Robert Michels (1999) [1962 by Crowell-Collier]. Political Parties. Transaction Publishers. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-4128-3116-1. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ Harald Wydra, Communism and the Emergence of Democracy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 22–27.

- ^ Military Study Warns of a Potentially Drastic Oil Crisis". Spiegel Online. September 1, 2010

Further reading

[edit]This "Further reading" section may need cleanup. (January 2016) |

- Appleby, Joyce. (1992). Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination. Harvard University Press.

- Archibugi, Daniele, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy, Princeton University Press ISBN 978-0-691-13490-1

- Becker, Peter, Heideking, Juergen, & Henretta, James A. (2002). Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750–1850. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80066-2

- Benhabib, Seyla. (1996). Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04478-1

- Blattberg, Charles. (2000). From Pluralist to Patriotic Politics: Putting Practice First, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-829688-1.

- Birch, Anthony H. (1993). The Concepts and Theories of Modern Democracy. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41463-0

- Bittar, Eduardo C. B. (2016). "Democracy, Justice and Human Rights: Studies of Critical Theory and Social Philosophy of Law". Saarbrucken: LAP, 2016. ISBN 978-3-659-86065-2

- Castiglione, Dario. (2005). "Republicanism and its Legacy." European Journal of Political Theory. pp 453–65.

- Copp, David, Jean Hampton, & John E. Roemer. (1993). The Idea of Democracy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43254-2

- Caputo, Nicholas. (2005). America's Bible of Democracy: Returning to the Constitution. SterlingHouse Publisher, Inc. ISBN 978-1-58501-092-9

- Dahl, Robert A. (1991). Democracy and its Critics. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04938-1

- Dahl, Robert A. (2000). On Democracy. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08455-9

- Dahl, Robert A. Ian Shapiro & Jose Antonio Cheibub. (2003). The Democracy Sourcebook. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54147-3

- Dahl, Robert A. (1963). A Preface to Democratic Theory. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-13426-0

- Davenport, Christian. (2007). State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86490-9

- Diamond, Larry & Marc Plattner. (1996). The Global Resurgence of Democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5304-3

- Diamond, Larry & Richard Gunther. (2001). Political Parties and Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6863-4

- Diamond, Larry & Leonardo Morlino. (2005). Assessing the Quality of Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8287-6

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner & Philip J. Costopoulos. (2005). World Religions and Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8080-3

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner & Daniel Brumberg. (2003). Islam and Democracy in the Middle East. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7847-3

- Elster, Jon. (1998). Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59696-1

- Emerson, Peter (2007) "Designing an All-Inclusive Democracy." Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-33163-6

- Emerson, Peter (2012) "Defining Democracy." Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-20903-1

- Everdell, William R. (2003) The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-22482-1.

- Gabardi, Wayne. (2001). Contemporary Models of Democracy. Polity.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. (1996). Democracy and Disagreement. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-19766-4

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. (2002). Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12019-5

- Haldane, Robert Burdone (1918). . London: Headley Bros. Publishers Ltd.

- Halperin, M. H., Siegle, J. T. & Weinstein, M. M. (2005). The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95052-7

- Hansen, Mogens Herman. (1991). The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18017-3

- Held, David. (2006). Models of Democracy. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5472-9

- Inglehart, Ronald. (1997). Modernisation and Postmodernisation. Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01180-6

- Isakhan, Ben and Stockwell, Stephen (co-editors). (2011) The Secret History of Democracy. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-24421-4

- Jarvie, I. C.; Milford, K. (2006). Karl Popper: Life and time, and values in a world of facts Volume 1 of Karl Popper: A Centenary Assessment, Karl Milford. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-5375-2.

- Khan, L. Ali. (2003). A Theory of Universal Democracy: Beyond the End of History. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-2003-8

- Köchler, Hans. (1987). The Crisis of Representative Democracy. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-8204-8843-2

- Lijphart, Arend. (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07893-0

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. (1959). "Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy". American Political Science Review. 53 (1): 69–105. doi:10.2307/1951731. JSTOR 1951731.

- Macpherson, C. B. (1977). The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-289106-8

- Morgan, Edmund. (1989). Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30623-1

- Mosley, Ivo (2003). Democracy, Fascism, and the New World Order. Imprint Academic. ISBN 0-907845-649.

- Mosley, Ivo (2013). In The Name Of The People. Imprint Academic. ISBN 9781845402624.

- Ober, J.; Hedrick, C. W. (1996). Dēmokratia: a conversation on democracies, ancient and modern. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01108-7.

- Plattner, Marc F. & Aleksander Smolar. (2000). Globalisation, Power, and Democracy. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6568-8

- Plattner, Marc F. & João Carlos Espada. (2000). The Democratic Invention. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6419-3

- Putnam, Robert. (2001). Making Democracy Work. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-5-551-09103-5

- Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Ober, Josiah; Wallace, Robert W (2007). Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24562-4.

- Riker, William H.. (1962). The Theory of Political Coalitions. Yale University Press.

- Sen, Amartya K. (1999). "Democracy as a Universal Value". Journal of Democracy. 10 (3): 3–17. doi:10.1353/jod.1999.0055. S2CID 54556373.

- Tannsjo, Torbjorn. (2008). Global Democracy: The Case for a World Government. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3499-6. Argues that not only is world government necessary if we want to deal successfully with global problems it is also, pace Kant and Rawls, desirable in its own right.

- Thompson, Dennis (1970). The Democratic Citizen: Social Science and Democratic Theory in the 20th Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13173-5

- Volk, Kyle G. (2014). Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weingast, Barry. (1997). "The Political Foundations of the Rule of Law and Democracy". American Political Science Review. 91 (2): 245–263. doi:10.2307/2952354. JSTOR 2952354.

- Weatherford, Jack. (1990). Indian Givers: How the Indians Transformed the World. New York: Fawcett Columbine. ISBN 978-0-449-90496-1

- Whitehead, Laurence. (2002). Emerging Market Democracies: East Asia and Latin America. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7219-8

- Willard, Charles Arthur. (1996). Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-89845-2

- Wood, E. M. (1995). Democracy Against Capitalism: Renewing historical materialism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47682-9

- Wood, Gordon S. (1991). The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-73688-2 examines democratic dimensions of republicanism

External links

[edit]- The Official Website of Democracy Foundation, Mumbai, India

- Centre for Democratic Network Governance

- Democracy at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Democracy

- The Economist Intelligence Unit's index of democracy

- Ewbank, N. The Nature of Athenian Democracy, Clio History Journal, 2009.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America Full hypertext with critical essays on America in 1831–32 from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Democracy Watch (Canada) – Leading democracy monitoring organisation

- Democratic Audit (UK) – Independent research organisation which produces evidence-based reports that assess democracy and human rights in the UK

- Data visualizations of data on democratisation and list of data sources on political regimes on 'Our World in Data', by Max Roser.

- [1] MaxRange Classifying political regime type and democracy level to all states and months 1789–2015

Category:Elections Category:Classical Greece Category:Greek inventions