User:Pie31415rre/sandbox

Performance measurement is the process of collecting, analyzing and/or reporting information regarding the performance of an individual, group, organization, system or component .[1]

Definitions of performance measurement tend to be predicated upon an assumption about why the performance is being measured.[2]

- Moullin defines the term with a forward looking organisational focus—"the process of evaluating how well organisations are managed and the value they deliver for customers and other stakeholders".[3]

- Neely et al. use a more operational retrospective focus—"the process of quantifying the efficiency and effectiveness of past actions".[4]

- In 2007 the Office of the Chief Information Officer in the USA defined it using a more evaluative focus—"Performance measurement estimates the parameters under which programs, investments, and acquisitions are reaching the targeted results".[5]

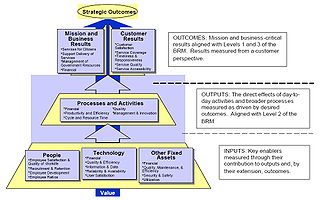

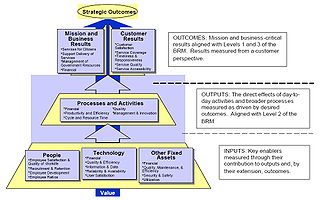

Performance Reference Model of the Federal Enterprise Architecture, 2005.[6]

Beyond a simple agreement about it being linked to some kind of measurement of performance there is little consensus about how to define or use performance measures. In the light of this what has happened is the emergence of organising frameworks that incorporate performance measures and often also proscribe methods for choosing and using the appropriate measures for that application. The most common such frameworks include:

- Balanced scorecard—used by organisations to manage the implementation of corporate strategies[7]

- Key performance indicator—a method for choosing important/critical performance measures, usually in an organisational context

Operational standards often include pre-defined lists of standard performance measures. For example EN 15341[8] identifies 71 performance indicators, whereof 21 are technical indicators, or those in a US Federal Government directive from 1999—National Partnership for Reinventing Government, USA; Balancing Measures: Best Practices in Performance Management, August 1999.

Defining performance measures or methods by which they can be chosen is also a popular activity for academics—for example a list of railway infrastructure indicators is offered by Stenström et al.,[9] a novel method for measure selection is proposed by Mendibil et al.[10]

Academic articles that provide critical reviews of performance measurement in specific domains are also common—e.g. Ittner's observations on non-financial reporting by commercial organisations,[11]; Boris et al.'s observations about use of performance measurement in non-profit organisations,[12] or Bühler et al.'s (2016) analysis of how external turbulence could be reflected in performance measurement systems.[13]

Performance Measurement Systems

[edit]Performance Measurement Matrix

[edit]Results-Determinant Framework

[edit]SMART pyramid

[edit]Balance Scorecard

[edit]Altri modelli

[edit]Contesti applicativi

[edit]Organizazioni No-Profit

[edit]Musei

[edit]Cultural Institutions / Teatri d'opera

[edit]Qualità

[edit]Misurazione

[edit]Dashboard

[edit]Trasformazione Digitale

[edit]a livello organizativo; vedere anche en:Digital Transformation

Istituzioni Pubbliche

[edit]Education

[edit]Cultural Institutions

[edit]Digital transformation is a pervasive phenomenon that involves transformations of key business operations, affects products, processes, organizational structures, management concepts (Matt et al., 2015), is driven by multiple factors and can have multiple objectives, so it is complex to implement it in a coherent and comprehensive way. To accomplish the objectives and transform organizations so the most challenging steps involve the capability to manage and put in practice digital transformation, implementing defined actions but also creating and correctly managing resources and capabilities. In this sense, many organizations have attempted to digitally transform their activities, but they have failed because of their lack of preparation, not having the right organizational structure, resources, abilities, and mindset.

In this sense critical success factors of digital transformation are the definition of a digital transformation strategy, the development of an appropriate culture, the definitions of figures in the governance that foster change and the presence of adequate digital competences.

The creation of a digital transformation strategy, made of plans and established procedures to cope with digital transformation complexity, is one of the main critical success factors for organizations interested in embracing and managing digital transformation. Digital transformation strategy has an ambivalent role, being at the same time an element that guides digital transformation and an element that is shaped from digital transformation evolution in time (Bharadwaj et al., 2013), and it can be considered a “central concept to integrate the entire coordination, prioritization, and implementation of digital transformations within a firm” (Matt et al., 2015). According to Voß & Pawlowski (Voß & Pawlowski, 2019) digital transformation strategy is a “blueprint that supports organizations in governing the transformations that arise owing to the integration of digital technologies, as well as in their operations after a transformation”.

the digital transformation strategy is comprehensive of aspects that IT strategy does not consider and aims to define a clear path for the transformation that results from the use of digital technologies. In order to formulate a strategy that has these characteristics Matt et al. (2015) introduce the concept of “Digital Transformation Framework” which is a strategic tool composed of four common dimensions that are chosen independently from the industry or firm in which they are applied. This tool is useful in the strategy formulation process but also ensure the successful rollout of the plan and help to exploit its intended effects. The four dimensions regard the “use of technologies”, which represents the ability of the firm to explore and use new digital tools, the “changes in value creation”, that reflect the impact that digital technologies have on the ability of the firm to create value, the “structural changes” which show the changes in processes, knowledge and organizational structure that are introduced to deal with new technologies, and the “financial aspects” which regard both the possible diminishing returns related to the decline of the core business and the need for capitals in order to finance the digital transformation process endeavour.

Because of the complexity to formulate a right strategy, Hess et al. (2016) also add some guidelines on how to approach the digital transformation and how to draft a related strategy thanks to the provision of a strategic set of options from which the management can chose for each of the previous four dimensions by Matt et al. (2015). Starting with the technologies dimension, it is possible to identify two different roles of IT: the “enabler” approach, which identify the IT as an enabler of new business opportunities, or the “supporter” which look at IT as a support function to reach defined business requirements and improvements. Also, the approach of organization towards new digital technologies can be as an “innovator” in case the firm is at the forefront of innovating with new technologies, “early adopter” when the firm actively looks for opportunity to implement new technologies and “follower” when instead it relies on established and widely used solutions. The organization can change the value creation modifying how it reach the customers in a digital way: for example, it can create electronic sales channels, new content-based platforms, or an extension of the classic product to digital channels. It can change the way in which the business create revenues such as paid content, freemium, advertising or through the selling of complementary products and can change the scope of the business linking it to content creation, content aggregation, content distribution or the management of content platforms.

To successfully manage digital transformation, organizations have also to define new duties for existing figures or new roles in charge of the digital transformation efforts that make possible to coordinate the related possibilities and understand all the implications for each structure and resource (Wolf et al., 2018). In particular, this introduction is necessary because often different layers of corporate management have a different view on digital transformation and so they could have a reduced ability to share a common view on it (Yucel, 2018b).

In some cases the organisations could extend the responsibilities of directors of the business units that are tackled by digital transformation, but in other cases there could be multiple new figures introduced: for example new cross-functional digital leadership committees or cross functional innovation groups that tackle the endeavour working closely with CEO (Chief Executive Officer) or CIO (Chief Information Officer) (Hess et al., 2016). In this case, choices have to be done moreover in defining if digital operations should be carried out by groups integrated into current structure of the organization or create new and separate entities (Hess et al., 2016).

In other cases, the Chief Digital Officer (CDO) position could be created. This translates in a figure that is in charge to oversee the improvement of digital skills, understand the industry-specific aspects of digital transformation, determine the consequent implications for the organization, develop and communicate a holistic digital transformation strategy to all the actors involved, and lead the required change efforts (Haffke et al., 2016).

Information systems (IS) lastly should assume an increased central role in business activities with new leadership roles and changes in responsibilities, becoming a central element to deploy the right digital strategy and manage the new digital activities. To do so they require a stricter alignment with the Chief Digital Officers (CDO) and the Chief Innovation Officers (CIO) (Haffke et al., 2016) and manage traditional IS with a bimodal approach, meaning that they have to combine traditional with new digital activities (Haffke et al., 2017).

Digital transformation requires also the creation of a new organizational culture that refer to the diversification of employees, the enhancement of knowledge exchange and communication, the need to open to collaborations, and the necessity to create flexibility to adapt to constant changes of the environment (Wolf et al., 2018).

Because the digital competences are not uniformly distributed among the workforce with the tendency of older ones to have problems in understanding the consequences of digital transformation, organizations should promote diversification in of employees being able to bring together access to resources and wisdom of older workers together with enthusiasm and experience in digital technologies by the youngest (Wolf et al., 2018). Moreover, organizations must exchange knowledge and information with transparency among all the departments and people because digital transformation is pervasive, and it applies to all the organization. This is a major challenge, considering that employees have less motivation to share knowledge or information because there is a danger that by doing so, and reducing the dependency between problems, experiences, solutions and themselves, they could become replaceable (Wolf et al., 2018). The lack of a collaboration culture among the organization furthermore could put in danger the results of digital transformation process in which, to develop product and services, it is necessary to create a collaborative and creative space (Wolf et al., 2018).

Competences and skills are considered a critical success factors for digital transformation too. Because technologies are a fundamental part in the process of change in the organizations, technology based skills are a major aspect, but they are also product-based and customer-based skills because thanks to digital transformation products are becoming more complex and consumers are more present and integrated in the value creation process (Liere-Netheler et al., 2018). The required skills can be acquired through an internal way, with a partnership (such as a joint cooperation within a certain project), with takeovers or through external sourcing (Hess et al., 2016) like the case of start-ups and specialised companies acquisitions. Although cooperation with start-ups could be problematic in the long term, the main goal in this case is to manage knowledge sharing in the short term (Wolf et al., 2018).

Digital Transformation implications

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Behn, Robert D. (2003). Why measure Performance? Different Purposes Require Different Measures.

- ^ Moullin, M. (2007) 'Performance measurement definitions. Linking performance measurement and organisational excellence', International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance,20:3,pp. 181-183.

- ^ Moullin, M. (2002), 'Delivering Excellence in Health and Social Care', Open University Press, Buckingham.

- ^ Neely, A.D., Adams, C. and Kennerley, M. (2002), The Performance Prism: The Scorecard for Measuring and Managing Stakeholder Relationships, Financial Times/Prentice Hall, London.

- ^ Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) Enterprise Architecture Program (2007). Treasury IT Performance Measures Guide Archived 2008-12-10 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Department of the Treasury. May 2007

- ^ FEA Consolidated Reference Model Document. whitehouse.gov May 2005.

- ^ Kaplan, Robert S.; Norton, David P. (September 1993). "Putting the Balanced Scorecard to Work". Harvard Business Review.

- ^ CEN (2007). EN 15341: Maintenance – Maintenance key performance indicators. European Committee for Standardization (CEN), Brussels.

- ^ Stenström, C.; Parida, A.; Galar, D. (2012). "Performance Indicators of Railway Infrastructure". International Journal of Railway Technology. 1 (3): 1–18. doi:10.4203/ijrt.1.3.1.

- ^ Mendibil, Kepa; Macbryde, Jillian, Designing effective team-based performance measurement systems: an integrated approach, Centre for Strategic Manufacturing, University of Strathclyde, James Weir Building, March 2005.

- ^ Ittner, Christopher D; Larcker, David F. (November 2003). "Coming up Short on Nonfinancial Performance Measurement". Harvard Business Review. 81 (11): 88–95, 139. PMID 14619154.

- ^ Boris, E. T., & Kopczynski Winkler, M. (2013). The Emergence of Performance Measurement as a Complement to Evaluation Among U.S. Foundations. New Directions For Evaluation, 2013(137), 69-80. doi:10.1002/ev.20047

- ^ Bühler, A., Wallenburg, C. M., & Wieland, A. (2016). Accounting for external turbulence of logistics organizations via performance measurement systems. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21(6), 694-708. doi:10.1108/SCM-02-2016-0040