User:Phlsph7/Metaphysics - Topics

Topics

[edit]Existence and categories of being

[edit]Metaphysicians often see existence or being as one of the most basic and general concepts.[1] To exist means to form part of reality and existence marks the difference between real entities and imaginary ones.[2] According to the orthodox view, existence is a second-order property or a property of properties: if an entity exists then its properties are instantiated.[3] A different position states that existence is a first-order property, meaning that it is similar to other properties of entities, such as shape or size.[4] It is controversial whether all entities have this property. According to Alexius Meinong, there are some objects that do not exist, including merely possible objects like Santa Claus and Pegasus.[5][a] A related question is whether existence is the same for all entities or whether there are different modes or degrees of existence.[7] For instance, Plato held that Platonic forms, which are perfect and immutable ideas, have a higher degree of existence than matter, which is only able to imperfectly mirror Platonic forms.[8]

Another key concern in metaphysics is the division of entities into different groups based on underlying features they have in common. Theories of categories provide a system of the most fundamental kinds or the highest genera of being by establishing a comprehensive inventory of everything.[9] One of the earliest theories of categories was provided by Aristotle, who proposed a system of 10 categories. Substances (e.g. man and horse), are the most important category since all other categories like quantity (e.g. four), quality (e.g. white), and place (e.g. in Athens) are said of substances and depend on them.[10] Kant understood categories as fundamental principles underlying human understanding and developed a system of 12 categories, which are divided into the four classes quantity, quality, relation, and modality.[11] More recent theories of categories were proposed by Edmund Husserl, Samuel Alexander, Roderick Chisholm, and E. J. Lowe.[12] Many philosophers rely on the contrast between concrete and abstract objects. According to a common view, concrete objects, like rocks, trees, and human beings, exist in space and time, undergo changes, and impact each other as cause and effect, while abstract objects, like numbers and sets, exist outside space and time, are immutable, and do not enter into causal relations.[13]

Particulars

[edit]Particulars are individual entities and include both concrete objects, like Aristotle, the Eiffel Tower, or a specific apple, and abstract objects, like the number 2 or a specific set in mathematics. Also called individuals,[b] they are unique, non-repeatable entities and contrast with universals, like the color red, which can at the same time exist in several places and characterize several particulars.[15] A widely held view is that particulars instantiate universals but are not themselves instantiated by something else, meaning that they exist in themselves while universals exist in something else. Substratum theory analyzes particulars as a substratum, also called bare particular, together with various properties. The substratum confers individuality to the particular while the properties express its qualitative features or what it is like. This approach is rejected by bundle theorists, who state that particulars are only bundles of properties without an underlying substratum. Some bundle theorists include in the bundle an individual essence, called haecceity, to ensure that each bundle is unique. Another proposal for concrete particulars is that they are individuated by their space-time location.[16]

Concrete particulars encountered in everyday life, like rocks, tables, and organisms, are complex entities composed of various parts. For example, a table is made up of a tabletop and legs, each of which is itself made up of countless particles. The relation between parts and wholes is studied by mereology.[17] The problem of the many is about which groups of entities form mereological wholes, for instance, whether a dust particle on the tabletop forms part of the table. According to mereological universalists, every collection of entities forms a whole, meaning that the parts of the table without the dust particle form one whole while they together with it form a second whole. Mereological moderatists hold that certain conditions have to be fulfilled for a group of entities to compose a whole, for example, that the entities touch one another. Mereological nihilists reject the idea that there are any wholes. They deny that, strictly speaking, there is a table and talk instead of particles that are arranged table-wise.[18] A related mereological problem is whether there are simple entities that have no parts, as atomists claim, or not, as continuum theorists contend.[19]

Universals

[edit]Universals are general entities, encompassing both properties and relations, that express what particulars are like and how they resemble one another. They are repeatable, meaning that they are not limited to a unique existent but can be instantiated by different particulars at the same time. For example, the particulars Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi instantiate the universal humanity, similar to how a strawberry and a ruby instantiate the universal red.[20]

A topic discussed since ancient philosophy, the problem of universals consists in the challenge of characterizing the ontological status of universals.[21] Realists argue that universals are real, mind-independent entities that exist in addition to particulars. According to Platonic realists, universals exist also independently of particulars, which implies that the universal red would continue to exist even if there were no red things. A more moderate form of realism, inspired by Aristotle, states that universals depend on particulars, meaning that they are only real if they are instantiated. Nominalists reject the idea that universals exist in either form. For them, the world is composed exclusively of particulars. The position of conceptualists constitutes a middle ground: they state that universals exist, but only as concepts in the mind used to order experience by classifying entities.[22]

Natural and social kinds are often understood as special types of universals. Entities belonging to the same natural kind share certain fundamental features characteristic of the structure of the natural world. In this regard, natural kinds are not an artificially made-up classification but are discovered,[c] usually by the natural sciences, and include kinds like electrons, H2O, and tigers. Scientific realists and anti-realists are in disagreement about whether natural kinds exist.[24] Social kinds are basic concepts used in the social sciences, such as race, gender, money, and disability.[25] They are studied by social metaphysics and group entities based on similarities they share from the perspective of certain practices, conventions, and institutions. They are often characterized as useful social constructions that, while not purely fictional, fail to reflect the fundamental structure of mind-independent reality.[26]

Possibility and necessity

[edit]The concepts of possibility and necessity convey what can or must be the case, expressed in statements like "it is possible to find a cure for cancer" and "it is necessary that two plus two equals four". They belong to modal metaphysics, which investigates the metaphysical principles underlying them, in particular, why it is the case that some modal statements are true while others are false.[27][d] Some metaphysicians hold that modality is a fundamental aspect of reality, meaning that besides facts about what is the case, there are additional facts about what could or must be the case.[29] A different view argues that modal truths are not about an independent aspect of reality but can be reduced to non-modal characteristics, for example, to facts about what properties or linguistic descriptions are compatible with each other or to fictional statements.[30]

Following Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, many metaphysicians use the concept of possible worlds to analyze the meaning and ontological ramifications of modal statements. A possible world is a complete and consistent way of how things could have been.[31] For example, the dinosaurs were wiped out in the actual world but there are possible worlds in which they are still alive.[32] According to possible world semantics, a statement is possibly true if it is true in at least one possible world while it is necessarily true if it is true in all possible worlds.[33] Modal realists argue that possible worlds exist as concrete entities in the same sense as the actual world, with the main difference being that the actual world is the world we live in while other possible worlds are inhabited by counterparts. This view is controversial and various alternatives have been suggested, for example, that possible worlds only exist as abstract objects or that they are similar to stories told in works of fiction.[34]

Space, time, and change

[edit]Space and time are dimensions that entities occupy. Spacetime realists state that space and time are fundamental aspects of reality and exist independently of the human mind. This view is rejected by spacetime idealists, who hold that space and time are constructions of the human mind in its attempt to organize and make sense of reality.[35] Spacetime absolutism or substantivalism understands spacetime as a distinct object, with some metaphysicians conceptualizing it as a box that contains all other entities within it. Spacetime relationism, by contrast, sees spacetime not as an object but as relations between objects, such as the spatial relation of being next to and the temporal relation of coming before.[36]

In the metaphysics of time, an important contrast is between the A-series and the B-series. According to the A-series theory, the flow of time is real, meaning that events are categorized into the past, present, and future. The present keeps moving forward in time and events that are in the present now will change their status and lie in the past later. From the perspective of the B-series theory, time is static and events are ordered by the temporal relations earlier-than and later-than without any essential difference between past, present, and future.[37] Eternalism holds that past, present, and future are equally real while according to presentists, only entities in the present exist.[38]

Material objects persist through time and undergo changes in the process, like a tree that grows or loses leaves.[39] The main ways of conceptualizing persistence through time are endurantism and perdurantism. According to endurantism, material objects are three-dimensional entities that are wholly present at each moment. As they undergo changes, they gain or lose properties but remain the same otherwise. Perdurantists see material objects as four-dimensional entities that extend through time and are made up of different temporal parts. At each moment, only one part of the object is present but not the object as a whole. Change means that an earlier part is qualitatively different from a later part. For example, if a banana ripens then there is an unripe part followed by a ripe part.[40]

Causality

[edit]Causality is the relation between cause and effect whereby one entity produces or affects another entity.[41] For instance, if a person bumps a glass and spills its contents then the bump is the cause and the spill is the effect.[42] Besides the single-case causation between particulars in this example, there is also general-case causation expressed in general statements such as "smoking causes cancer".[43] The term agent causation is used if people and their actions cause something.[44] Causation is usually interpreted deterministically, meaning that a cause always brings about its effect. This view is rejected by probabilistic theories, which claim that the cause merely increases the probability that the effect occurs. This view can be used to explain that smoking causes cancer even though this is not true in every single case.[45]

The regularity theory of causation, inspired by David Hume's philosophy, states that causation is nothing but a constant conjunction in which the mind apprehends that one phenomenon, like putting one's hand in a fire, is always followed by another phenomenon, like a feeling of pain.[46] According to nomic regularity theories, the regularities take the forms of laws of nature studied by science.[47] Counterfactual theories focus not on regularities but on how effects depend on their causes. They state that effects owe their existence to the cause and would not be present without them.[48] According to primitivism, causation is a basic concept that cannot be analyzed in terms of non-causal concepts, such as regularities or dependence relations. One form of primitivism identifies causal powers inherent in entities as the underlying mechanism.[49] Eliminativists reject the above theories by holding that there is no causation.[50]

Mind and free will

[edit]

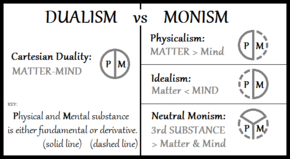

Mind encompasses phenomena like thinking, perceiving, feeling, and desiring as well as the underlying faculties responsible for these phenomena.[51] The mind–body problem is the challenge of clarifying the relation between physical and mental phenomena. According to Cartesian dualism, minds and bodies are distinct substances. They causally interact with each other in various ways but can, at least in principle, exist on their own.[52] This view is rejected by monists, who argue that reality is made up of only one kind. According to idealism, everything is mental, including physical objects, which may be understood as ideas or perceptions of conscious minds. Materialists, by contrast, state that all reality is at its core material. Some deny that mind exists but the more common approach is to explain mind in terms of certain aspects of matter, such as brain states, behavioral dispositions, or functional roles.[53] Neutral monists argue that reality is fundamentally neither material nor mental and suggest that matter and mind are both derivative phenomena.[54] A key aspect of the mind–body problem is the hard problem of consciousness, which concerns the question of how physical systems like brains can produce phenomenal consciousness.[55]

The status of free will as the ability of a person to choose their actions is a central aspect of the mind–body problem.[56] Metaphysicians are interested in the relation between free will and causal determinism, the view that everything in the universe, including human behavior, is determined by preceding events and laws of nature. It is controversial whether causal determinism is true, and, if so, whether this would imply that there is no free will. According to incompatibilism, free will cannot exist in a deterministic world since there is no true choice or control if everything is determined. Hard determinists infer from this observation that there is no free will while libertarians conclude that determinism must be false. Compatibilists take a third approach by arguing that determinism and free will do not exclude each other, for instance, because a person can still act in tune with their motivation and choices even if they are determined by other forces. Free will plays a key role in ethics in regard to the moral responsibility people have for what they do.[57]

Others

[edit]Identity is a relation that every entity has to itself as a form of sameness. It refers to numerical identity when the very same entity is involved, as in "the morning star is the evening star". In a slightly different sense, it encompasses qualitative identity, also called exact similarity and indiscernibility, which is the case when two distinct entities are exactly alike, such as perfect identical twins.[58] The principle of the indiscernibility of identicals is widely accepted and holds that numerically identical entities exactly resemble one another. The converse principle, known as identity of indiscernibles, is more controversial and states that two entities are numerically identical if they exactly resemble one another.[59] Another distinction is between synchronic and diachronic identity. Synchronic identity relates an entity to itself at the same time while diachronic identity is about the same entity at different times, as in statements like "the table I bought last year is the same as the table in my dining room now".[60] Personal identity is a related topic in metaphysics that uses the term identity in a slightly different sense and concerns questions like what personhood is or what makes someone a person.[61]

Various contemporary metaphysicians rely on the concepts of truth and truthmakers to conduct their inquiry.[62] Truth is a property of linguistic statements or mental representations that are in accord with reality. A truthmaker of a statement is the entity whose existence makes the statement true.[63] For example, the statement "a tomato is red" is true because there exists a red tomato as its truthmaker.[64] Based on this observation, it is possible to pursue metaphysical research by asking what the truthmakers of statements are, with different areas of metaphysics being dedicated to different types of statements. According to this view, modal metaphysics asks what makes statements about what is possible and necessary true while the metaphysics of time is interested in the truthmakers of temporal statements about the past, present, and future.[65]

Sources

[edit]- Liston, Michael. "Scientific Realism and Antirealism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- Rea, Michael C. (2021). Metaphysics: The Basics (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-13607-9.

- Gallois, Andre (2016). "Identity Over Time". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- Korfmacher, Carsten. "Personal Identity". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- Olson, Eric T. (2023). "Personal Identity". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- Noonan, Harold; Curtis, Ben (2022). "Identity". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- Sleigh, R. C. (2005). "identity of indiscernibles". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Kirwan, Christopher (2005). "Identity". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Asay, Jamin (2020). A Theory of Truthmaking: Metaphysics, Ontology, and Reality. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-60404-8.

- Imaguire, Guido (2018). Priority Nominalism: Grounding Ostrich Nominalism as a Solution to the Problem of Universals. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-95004-4.

- Lowe, E. J. (2005a). "truth". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Olson, Eric T. (2001). "Mind–Body Problem". In Blakemore, Colin; Jennett, Sheila (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852403-8.

- Armstrong, D. M. (2018). The Mind-body Problem: An Opinionated Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-96480-0.

- Timpe, Kevin. "Free Will". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- O’Connor, Timothy; Franklin, Christopher (2022). "Free Will". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- Weisberg, Josh. "Hard Problem of Consciousness". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Stubenberg, Leopold; Wishon, Donovan (2023). "Neutral Monism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Griffin, Nicholas (1998). "Neutral monism". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N035-1. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Ramsey, William (2022). "Eliminative Materialism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- McLaughlin, Brian P. (1999). Audi, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63722-0.

- Morton, Adam (2005). "Mind". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Kim, Jaegwon (2005). "Mind, Problems of the Philosophy of". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Williamson, John (2012). "Probabilistic Theories". In Beebee, Helen; Hitchcock, Christopher; Menzies, Peter (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Causation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-162946-4.

- Mumford, Stephen; Anjum, Rani Lill (2013). "8. Primitivism: is causation the most basic thing?". Causation: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968443-4.

- Mumford, Stephen (2009). "Passing Powers Around". Monist. 92 (1). doi:10.5840/monist20099215.

- Lorkowski, C. M. "Hume, David: Causation". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Romero, Gustavo E. (2018). Scientific Philosophy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-97631-0.

- Benovsky, Jiri (2016). Meta-metaphysics: On Metaphysical Equivalence, Primitiveness, and Theory Choice. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-25334-3.

- Hoefer, Carl; Huggett, Nick; Read, James (2023). "Absolute and Relational Space and Motion: Classical Theories". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Pelczar, Michael (2015). Sensorama: A Phenomenalist Analysis of Spacetime and Its Contents. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-104706-0.

- Janiak, Andrew (2022). "Kant's Views on Space and Time". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Dainton, Barry (2010). "Spatial anti-realism". Time and Space (2 ed.). Acumen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84465-190-0.

- Dyke, Heather (2002). "McTaggart and the Truth about Time". In Callender, Craig (ed.). Time, Reality and Experience. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52967-9.

- Hawley, Katherine (2023). "Temporal Parts". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Simons, Peter (2013). "The Thread of Persistence". In Kanzian, Christian (ed.). Persistence. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-032705-2.

- Costa, Damiano. "Persistence in Time". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Miller, Kristie (2018). "Persistence". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. doi:10.4324/0123456789-N126-1. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Ásta (2017). "Social Kinds". The Routledge Handbook of Collective Intentionality. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-76857-1.

- Bird, Alexander; Tobin, Emma (2024). "Natural Kinds". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Brzović, Zdenka. "Natural Kinds". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- Rodriguez-Pereyra, Gonzalo (2000). "What is the problem of universals?". Mind. 109 (434). doi:10.1093/mind/109.434.255.

- Cowling, Sam (2019). "Universals". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N065-2. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- Bigelow, John C. (1998a). "Universals". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N065-1. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- Tallant, Jonathan (2017). Metaphysics: An Introduction (Second ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-3500-0671-3.

- Cornell, David. "Material Composition". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- Varzi, Achille (2019). "Mereology". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- Brenner, Andrew (2015). "Mereological nihilism and the special arrangement question". Synthese. 192 (5). doi:10.1007/s11229-014-0619-7.

- Berryman, Sylvia (2022). "Ancient Atomism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- Maurin, Anna-Sofia (2019). Particulars. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N040-2.

- Bigelow, John C. (1998). "Particulars". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N040-1. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- MacLeod, Mary C.; Rubenstein, Eric M. "Universals". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Lowe, E. J. (1 January 2005). "particulars and non-particulars". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. (22 November 2010). "Possible Worlds in History of Science". In Sture, Allén (ed.). Possible Worlds in Humanities, Arts and Sciences: Proceedings of Nobel Symposium 65. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-086685-8.

- Berto, Francesco; Jago, Mark (2023). "Impossible Worlds". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- Pavel, Thomas G. (1986). Fictional Worlds. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-29966-5. Archived from the original on 2024-02-17. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- Menzel, Christopher (2023). "Possible Worlds". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- Hale, Bob (26 June 2020). Essence and Existence. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-259622-2.

- Hanna, Robert (23 January 2009). Rationality and Logic. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-26311-5.

- Wilsch, Tobias (October 2017). "Sophisticated Modal Primitivism". Philosophical Issues. 27 (1). doi:10.1111/phis.12100.

- Nuttall, Jon (3 July 2013). An Introduction to Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-6807-9.

- Goswick, Dana (25 October 2018). "6. Are Modal Facts Brute Facts?". In Vintiadis, Elly; Mekios, Constantinos (eds.). Brute Facts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-875860-0.

- Parent, Ted. "Modal Metaphysics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- Macnamara, John (22 September 2009). Through the Rearview Mirror: Historical Reflections on Psychology. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-26367-2.

- Erasmus, Jacobus (8 January 2018). The Kalām Cosmological Argument: A Reassessment. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-73438-5.

- Falguera, José L.; Martínez-Vidal, Concha; Rosen, Gideon (2022). "Abstract Objects". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- Grim, Patrick; Rescher, Nicholas (5 September 2023). Theory of Categories: Key Instruments of Human Understanding. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-83998-815-8.

- Studtmann, Paul (2024). "Aristotle's Categories". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- White, Alan (6 March 2019). Methods of Metaphysics. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-51427-2.

- Gibson, Q. B. (31 July 1998). The Existence Principle. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-7923-5188-7. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- Vallicella, William F. (2010). A Paradigm theory of existence: Onto-Theology vindicated. Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-90-481-6128-7.

- Wardy, Robert (1998). "Categories". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-N005-1. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^

- Lowe 2005, p. 277

- White 2019, pp. 135, 200

- Gibson 1998, pp. 1–2

- Shand 2004, pp. 47–48

- Vallicella 2010, p. 16

- ^

- ^

- Casati & Fujikawa, lead section, §1. Existence as a Second-Order Property and Its Relation to Quantification

- Blackburn 2008, existence

- ^

- Casati & Fujikawa, lead section, §2. Existence as a First-Order Property and Its Relation to Quantification

- Blackburn 2008, existence

- ^

- Van Inwagen 2023

- Nelson 2022, lead section, §2. Meinongianism

- Shand 2004, p. 49

- ^

- Van Inwagen 2023

- Nelson 2022, lead section, §2. Meinongianism

- Shand 2004, p. 49

- ^

- Casati & Fujikawa, lead section, §3. How Many Ways of Being Existent?

- McDaniel 2017, p. 77

- ^

- Poidevin et al. 2009, pp. 227–228

- Van Inwagen 2023

- ^

- Thomasson 2022, Lead Section

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 11–12

- Wardy 1998, Lead Section

- ^

- Thomasson 2022, § 1.1 Aristotelian Realism

- Studtmann 2024, § 2. The Ten-Fold Division

- Wardy 1998, § 1. Categories in Aristotle

- ^

- Thomasson 2022, § 1.2 Kantian Conceptualism

- Wardy 1998, § 1. Categories in Kant

- ^

- Thomasson 2022, § 1.3 Husserlian Descriptivism, § 1.4 Contemporary Category Systems

- Grim & Rescher 2023, p. 39

- ^

- Falguera, Martínez-Vidal & Rosen 2022, Lead Section, § 1. Introduction, § 3.5 The Ways of Negation

- Erasmus 2018, p. 93

- Macnamara 2009, p. 94

- ^ Bigelow 1998, Lead Section

- ^

- Lowe 2005, p. 683

- MacLeod & Rubenstein, Lead Section, § 1a. The Nature of Universals

- Bigelow 1998, Lead Section

- Campbell 2006, § Particularity and individuality

- Maurin 2019, Lead Section

- ^

- Maurin 2019, Lead Section

- Campbell 2006, § Particularity and individuality

- Bigelow 1998, Lead Section, § 3. Bundles of properties

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 82–83

- ^

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 250–251

- Varzi 2019, Lead Section, § 1. 'Part' and Parthood

- Cornell, Lead Section, § 2. The Special Composition Question

- Tallant 2017, pp. 19–21

- ^

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 82–83

- Cornell, Lead Section, § 2. The Special Composition Question

- Brenner 2015, p. 1295

- Tallant 2017, pp. 19–21, 23–24, 32–33

- ^

- Berryman 2022, § 2.6 Atomism and Particle Theories in Ancient Greek Sciences

- Varzi 2019, § 3.4 Atomism, Gunk, and Other Options

- ^

- MacLeod & Rubenstein, Lead Section

- Bigelow 1998a, Lead Section

- Cowling 2019, Lead Section

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 17–19

- ^

- MacLeod & Rubenstein, Lead Section, § 1c. The Problem of Universals

- Rodriguez-Pereyra 2000, pp. 255–256

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 17–19

- ^

- MacLeod & Rubenstein, Lead Section, § 2. Versions of Realism, § 3. Versions of Anti-Realism

- Bigelow 1998a, § 4. Nominalism and Realism

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 17–19, 45

- ^

- Brzović, Lead Section

- Bird & Tobin 2024, Lead Section

- ^

- Brzović, Lead Section, § 3. Metaphysics of Natural Kinds

- Bird & Tobin 2024, Lead Section, § 1.2 Natural Kind Realism

- Liston, Lead Section

- ^

- Ásta 2017, pp. 290–291

- Bird & Tobin 2024, § 2.4 Natural Kinds and Social Science

- ^

- ^

- Parent, Lead Section

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 149–150

- Koons & Pickavance 2015, pp. 154–155

- Mumford 2012, § 8. What is possible?

- ^

- Hanna 2009, p. 196

- Hale 2020, p. 142

- ^

- Goswick 2018, pp. 97–98

- Wilsch 2017, pp. 428–429, 446

- ^

- Goswick 2018, pp. 97–98

- Parent, § 3. Ersatzism, § 4. Fictionalism

- Wilsch 2017, pp. 428–429

- ^

- Menzel 2023, Lead Section, § 1. Possible Worlds and Modal Logic

- Berto & Jago 2023, Lead Section

- Pavel 1986, p. 50

- Campbell 2006, § Possible Worlds

- ^ Nuttall 2013, p. 135

- ^

- Menzel 2023, Lead Section, § 1. Possible Worlds and Modal Logic

- Kuhn 2010, p. 13

- ^

- Parent, Lead Section, § 2. Lewis' Realism, § 3. Ersatzism, § 4. Fictionalism

- Menzel 2023, Lead Section, § 2. Three Philosophical Conceptions of Possible Worlds

- Campbell 2006, § Modal Realism

- ^

- Dainton 2010, pp. 245–246

- Janiak 2022, § 4.2 Absolute/relational vs. real/ideal

- Pelczar 2015, p. 115

- ^

- Hoefer, Huggett & Read 2023, Lead Section

- Benovsky 2016, pp. 19–20

- Romero 2018, p. 135

- ^

- Dyke 2002, p. 138

- Koons & Pickavance 2015, pp. 182–185

- Carroll & Markosian 2010, pp. 160–161

- ^

- Carroll & Markosian 2010, pp. 179–181

- Loux & Crisp 2017, pp. 206, 214–215

- Romero 2018, p. 135

- ^

- Miller 2018, Lead Section

- Costa, Lead Section

- Simons 2013, p. 166

- ^

- Miller 2018, Lead Section

- Costa, Lead Section, § 1. Theories of Persistence

- Simons 2013, p. 166

- Hawley 2023, 3. Change and Temporal Parts

- ^

- Carroll & Markosian 2010, pp. 20–22

- Tallant 2017, pp. 218–219

- ^ Carroll & Markosian 2010, p. 20

- ^

- Carroll & Markosian 2010, pp. 21–22

- Williamson 2012, p. 186

- ^

- Ney 2014, pp. 219, 252–253

- Tallant 2017, pp. 233–234

- ^

- Ney 2014, pp. 228–231

- Williamson 2012, pp. 185–186

- ^

- Lorkowski, Lead Section, § 2. Necessary Connections and Hume’s Two Definitions, § 4. Causal Reductionism

- Carroll & Markosian 2010, pp. 24–25

- Tallant 2017, pp. 220–221

- ^ Ney 2014, pp. 223–224

- ^

- Carroll & Markosian 2010, p. 26

- Tallant 2017, pp. 221–222

- Ney 2014, pp. 224–225

- ^

- Ney 2014, pp. 231–232

- Mumford 2009, pp. 94–95

- Mumford & Anjum 2013

- Koons & Pickavance 2015, pp. 63–64

- ^ Tallant 2017, pp. 231–232

- ^ Morton 2005, p. 603

- ^

- McLaughlin 1999, pp. 684–685

- Kim 2005, p. 608

- ^

- McLaughlin 1999, pp. 685–691

- Kim 2005, p. 608

- Ramsey 2022, Lead Section

- ^

- Stubenberg & Wishon 2023, Lead Section; § 1.3 Mind and Matter Revisited

- Griffin 1998

- ^ Weisberg, Lead Section, § 1. Stating the Problem

- ^

- Timpe, Lead Section

- Olson 2001, Mind–Body Problem

- Armstrong 2018, p. 94

- ^

- O’Connor & Franklin 2022, Lead Section, § 2. The Nature of Free Will

- Timpe, Lead Section, § 1. Free Will, Free Action and Moral Responsibility, § 3. Free Will and Determinism

- Armstrong 2018, p. 94

- ^

- Kirwan 2005, pp. 417–418

- Noonan & Curtis 2022, Lead Section

- ^

- Sleigh 2005, p. 418

- Kirwan 2005, pp. 417–418

- Noonan & Curtis 2022, § 2. The Logic of Identity

- ^

- Gallois 2016, § 2.1 Diachronic and Synchronic Identity

- Noonan & Curtis 2022, Lead Section, § 5. Identity over time

- ^

- Noonan & Curtis 2022, Lead Section

- Olson 2023, Lead Section, § 1. The Problems of Personal Identity

- Korfmacher

- ^

- Tallant 2017, pp. 1–4

- Koons & Pickavance 2015, pp. 15–17

- ^

- Lowe 2005a, p. 926

- Imaguire 2018, p. 34

- Tallant 2017, pp. 1–4

- Koons & Pickavance 2015, pp. 15–17

- Asay 2020, p. 11

- ^ Tallant 2017, p. 1

- ^

- Tallant 2017, pp. 1–4, 163–165

- Koons & Pickavance 2015, pp. 15–17, 154

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).