User:Phaisit16207/sandbox/Russian Empire

Russian Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1721–1917 | |||||||||||

Coat of arms

(1883–1917) | |||||||||||

| Motto: "Съ нами Богъ!" S nami Bog! ("God is with us!") | |||||||||||

| Anthem: Боже, Царя храни! Bozhe Tsarya khrani! ("God Save the Tsar!") For further anthems: see List of anthems in the Russian Empire | |||||||||||

| Greater coat of arms (1882–1917): | |||||||||||

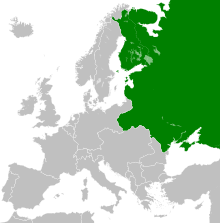

Location of all territories which controlled by Russian Empire in 1866 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Sankt-Peterburg (1721–1728; 1730–1917)[c] Moskva (1728–1730)[2] | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Russian | ||||||||||

| Recognised languages | Polish, German (in Baltic provinces), Finnish, Swedish, Ukrainian, Chinese (in Dalian) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Majority: 71.10% Orthodox (official)[3] Minorities: 11.07% Muslim 9.16% Catholic 4.16% Jewish 3.00% Protestant 0.94% Armenian 0.56% other | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary absolute monarchy (1721–1906) Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy[4] (1906–1917) | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1721–1725 (first) | Peter I | ||||||||||

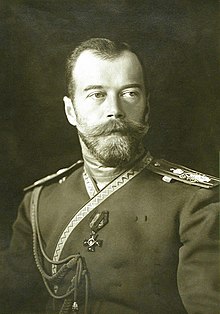

• 1894–1917 (last) | Nicholas II | ||||||||||

• 1810–1812 (first) | Nikolai Rumyantsev[d] | ||||||||||

• 1917 (last) | Nikolai Golitsyn[e] | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Governing Senate[5] | ||||||||||

| State Council (1810–1917) | |||||||||||

| State Duma (1905–1917) | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 10 September 1721 | |||||||||||

• Proclaimed | 2 November 1721 | ||||||||||

| 4 February 1722 | |||||||||||

| 26 December 1825 | |||||||||||

| 3 March 1861 | |||||||||||

| 18 October 1867 | |||||||||||

| January 1905 – July 1907 | |||||||||||

| 30 October 1905 | |||||||||||

• Constitution adopted | 6 May 1906 | ||||||||||

| 8–16 March 1917 | |||||||||||

• Republic proclaimed | 14 September 1917 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1895[6][7] | 22,800,000 km2 (8,800,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1897 | 125,640,021 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Russian ruble | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Russian Empire,[f] also known as Imperial Russia, was the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of neighbouring rival powers: the Swedish Empire, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Qajar Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Qing China. It also held colonies in North America between 1799 and 1867. Covering an area of approximately 22,800,000 square kilometres (8,800,000 sq mi), it remains the third-largest empire in history, surpassed only by the British Empire and the Mongol Empire; it ruled over a population of 125.6 million people per the 1897 Russian census, which was the only census carried out during the entire imperial period. Owing to its geographic extent across three continents at its peak, it featured great ethnic, linguistic, religious, and economic diversity.

From the 10th–17th centuries, the land was ruled by a noble class known as the boyars, above whom was a tsar (later adapted as the "Emperor of all the Russias"). The groundwork leading up to the establishment of the Russian Empire was laid by Ivan III (1462–1505): he tripled the territory of the Russian state and laid its foundation, renovating the Moscow Kremlin and also ending the dominance of the Golden Horde. From 1721 until 1762, the Russian Empire was ruled by the House of Romanov; its matrilineal branch of patrilineal German descent, the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov, ruled from 1762 until 1917. At the beginning of the 19th century, the territory of the Russian Empire extended from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Black Sea in the south, and from the Baltic Sea in the west to Alaska, Hawaii, and California in the east. By the end of the 19th century, it had expanded its control over most of Central Asia and parts of Northeast Asia.

Peter I (1682–1725) fought numerous wars and expanded an already vast empire into a major power of Europe. During his rule, he moved the Russian capital from Moscow to the new model city of Saint Petersburg, which was largely built according to designs of the Western world; he also led a cultural revolution that replaced some of the traditionalist and medieval socio-political customs with a modern, scientific, rationalist, and Western-oriented system. Catherine the Great (1762–1796) presided over a golden age: she expanded the Russian state by conquest, colonization, and diplomacy, while continuing Peter I's policy of modernization towards a Western model. Alexander I (1801–1825) played a major role in defeating the militaristic ambitions of Napoleon and subsequently constituting the Holy Alliance, which aimed to restrain the rise of secularism and liberalism across Europe. The Russian Empire further expanded to the west, south, and east, concurrently establishing itself as one of the most powerful European powers. Its victories in the Russo-Turkish Wars were later checked by defeat in the Crimean War (1853–1856), leading to a period of reform and intensified expansion into Central Asia.[8] Alexander II (1855–1881) initiated numerous reforms, most notably the 1861 emancipation of all 23 million serfs. His official policy involved the responsibility of the Russian Empire towards the protection of Eastern Orthodox Christians residing within the Ottoman-ruled territories of Europe; this was one factor that later led to the Russian entry into World War I on the side of the Allied Powers against the Central Powers.

Until the 1905 Russian Revolution, the Russian Empire functioned as an absolute monarchy, following which a semi-constitutional monarchy was nominally established. However, it functioned poorly during World War I, leading to the February Revolution. With the abdication of Nicholas II in 1917, the monarchy was abolished. In the aftermath of the February Revolution, the short-lived Russian Provisional Government proclaimed the establishment of the Russian Republic as a successor across its territories.[9][10]The October Revolution saw the Bolsheviks seize power in the Russian Republic, sparking the Russian Civil War. In 1918, the Bolsheviks executed the Romanov family, and after emerging victorious from the Russian Civil War in 1922–1923, they established the Soviet Union across most of the territory of the former Russian Empire.

Background

[edit]Reformation of Peter I

[edit]The foundations of the Russian Empire laid during Peter I's reforms, which significantly altered Russia's political and social structure,[11] and as a result of the Great Northern War, which strengthened Russia's standing on the world stage.[12] Internal transformations and military victories contributed to the transformation of Russia into a great power, playing a big role in European politics.[12] Given the realities of the new situation in the country, the Senate and Synod on 2 November [O.S. 22 October] 1721, on the day of the announcement of the Treaty of Nystad, presented the Tsar with the titles of the Pater Patriae (Russian: Отец отечества, romanized: Otets otechestva, IPA: [ɐˈtrʲet͡s ɐˈtʲet͡ɕɪstvə]) and the Emperor of all the Russias.[13] It is generally accepted that with the adoption of the imperial title by Peter I, Russia turned from a tsardom into an empire, and the imperial period began in the history of the country.[14][15][16]

Following the reforms, Russia became ruled by an absolute monarchy. The Military Regulations made a note of the autocracy regime.[g] Even though the Holy Synod's chief prosecutor served as the church's link to the head of state, Peter I changed the patriarchal system that had previously existed into a synodal one. During the reign of Peter I, the last vestiges of a boyar's independence were lost. He transformed them into nobility, who were obedient nobles who served the state for the rest of their lives. He also introduced the Table of Ranks and equated the Votchina with an estate. Russia's modern fleet was built by Peter the Great, along with an army that was reformed in the manner of European style and educational institutions (the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences). Civil lettering was adopted during Peter I's reign, and the first Russian newspaper, Vedomosti, was published. Peter I promoted the advancement of science, particularly geography and geology, trade, and industry,[17] including shipbuilding, as well as the growth of the Russian educational system. Every tenth Russian acquired an education during Peter I's reign, when there were 15 million people in the country.[18] The city of Saint Petersburg, which was built in 1703 on territory along the Baltic coast that had been conquered during the Great Northern War, served as the state's capital.

This concept of the triune Russian people, composed of the Great Russians, the Little Russians, and the Belorussians (White Russians), was introduced during the reign of Peter I, and it was associated with the name of Archimandrite Zakhary Kopystensky (1621), the Archimandrite of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. Afterwards, the concept was developed in the writings of an associate of Peter I, Archbishop Professor Feofan Prokopovich. Several of Peter I's associates are well-known, including François Le Fort, Boris Sheremetev, Alexander Menshikov, Jacob Bruce, Mikhail Golitsyn, Anikita Repnin, and Alexey Kelin. During Peter's reign, the nobility was still required to serve, and serf labour played a significant role in the growth of the industry; therefore, Peter's objectives required the preservation of antiquated traditions. The volume of the country's international trade turnover increased as a result of Peter I's industrial reforms. However, imports of goods overtook exports, strengthening the role of foreigners in Russian trade, particularly the British domination.[19]

History

[edit]18th century

[edit]Peter the Great (1672–1725)

[edit]

Peter I (1672–1725)—also referred to as Peter the Great—played a major role in introducing the European state system into the Russian Empire. While the empire's vast lands had a population of 14 million, grain yields trailed behind those in the West.[20] Nearly the entire population was devoted to agriculture, with only a small percentage living in towns. The class of kholops, whose status was close to that of slaves, remained a major institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter converted household kholops into house serfs, thus counting them for poll taxation. Russian agricultural kholops had been formally converted into serfs earlier in 1679. They were largely tied to the land, in a feudal sense, until the late nineteenth century.

Peter's first military efforts were directed against the Ottoman Turks. His attention then turned to the north. Russia lacked a secure northern seaport, except at Archangel on the White Sea, where the harbor was frozen for nine months a year. Access to the Baltic Sea was blocked by Sweden, whose territory enclosed it on three sides. Peter's ambitions for a "window to the sea" led him, in 1699, to make a secret alliance with Saxony, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and Denmark against Sweden; they conducted the Great Northern War, which ended in 1721 when an exhausted Sweden asked for peace with Russia.

As a result, Peter acquired four provinces situated south and east of the Gulf of Finland, securing access to the sea. There he built Russia's new capital, Saint Petersburg, on the Neva River, to replace Moscow, which had long been Russia's cultural center. This relocation expressed his intent to adopt European elements for his empire. Many of the government and other major buildings were designed under Italianate influence. In 1722, he turned his aspirations toward increasing Russian influence in the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea at the expense of the weakened Safavid Persians. He made Astrakhan the centre of military efforts against Persia, and waged the first full-scale war against them in 1722–23.[21] Peter the Great temporarily annexed several areas of Iran to Russia, which after the death of Peter were returned in the 1732 Treaty of Resht and 1735 Treaty of Ganja as a deal to oppose the Ottomans.[22]

Peter reorganized his government based on the latest political models of the time, molding Russia into an absolutist state. He replaced the old boyar Duma (council of nobles) with a nine-member Senate, in effect a supreme council of state. The countryside was divided into new provinces and districts. Peter told the Senate that its mission was to collect taxes, and tax revenues tripled over the course of his reign. Meanwhile, all vestiges of local self-government were removed. Peter continued and intensified his predecessors' requirement of state service from all nobles, in the Table of Ranks.

As part of Peter's reorganisation, he also enacted a church reform. The Russian Orthodox Church was partially incorporated into the country's administrative structure, in effect making it a tool of the state. Peter abolished the patriarchate and replaced it with a collective body, the Holy Synod, which was led by a government official.[23]

Peter died in 1725, leaving an unsettled succession. After a short reign by his widow, Catherine I, the crown passed to empress Anna. She slowed the reforms and led a successful war against the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in a significant weakening of the Crimean Khanate, an Ottoman vassal and long-term Russian adversary.

The discontent over the dominant positions of Baltic Germans in Russian politics resulted in Peter I's daughter Elizabeth being put on the Russian throne. Elizabeth supported the arts, architecture, and the sciences (for example, the founding of Moscow University). But she did not carry out significant structural reforms. Her reign, which lasted nearly 20 years, is also known for Russia's involvement in the Seven Years' War, where it was successful militarily, but gained little politically.[24]

Catherine the Great (1762–1796)

[edit]

Catherine the Great was a German princess who married Peter III, the German heir to the Russian crown. After the death of Empress Elizabeth, Catherine came to power after she effected a coup d'état against her unpopular husband. She contributed to the resurgence of the Russian nobility that began after the death of Peter the Great, abolishing State service and granting them control of most state functions in the provinces. She also removed the tax on beards instituted by Peter the Great.[25]

Catherine extended Russian political control over the lands of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, supporting the Targowica Confederation. However, the cost of these campaigns further burdened the already oppressive social system, under which serfs were required to spend almost all of their time laboring on their owners' land. A major peasant uprising took place in 1773, after Catherine legalised the selling of serfs separate from land. Inspired by a Cossack named Yemelyan Pugachev and proclaiming "Hang all the landlords!", the rebels threatened to take Moscow before they were ruthlessly suppressed. Instead of imposing the traditional punishment of drawing and quartering, Catherine issued secret instructions that the executioners should execute death sentences quickly and with minimal suffering, as part of her effort to introduce compassion into the law.[26] She furthered these efforts by ordering the public trial of Darya Nikolayevna Saltykova, a high-ranking nobleman, on charges of torturing and murdering serfs. Whilst these gestures garnered Catherine much positive attention from Europe during the Enlightenment, the specter of revolution and disorder continued to haunt her and her successors. Indeed, her son Paul introduced a number of increasingly erratic decrees in his short reign aimed directly against the spread of French culture in response to their revolution.

In order to ensure the continued support of the nobility, which was essential to her reign, Catherine was obliged to strengthen their authority and power at the expense of the serfs and other lower classes. Nevertheless, Catherine realized that serfdom must eventually be ended, going so far in her Nakaz ("Instruction") to say that serfs were "just as good as we are" – a comment received with disgust by the nobility. Catherine advanced Russia's southern and western frontiers, successfully waging war against the Ottoman Empire for territory near the Black Sea, and incorporating territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Partitions of Poland, alongside Austria and Prussia. As part of the Treaty of Georgievsk, signed with the Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, and her own political aspirations, Catherine waged a new war against Persia in 1796 after they had invaded eastern Georgia. Upon achieving victory, she established Russian rule over it and expelled the newly established Persian garrisons in the Caucasus.

Catherine's expansionist policy caused Russia to develop into a major European power,[27] as did the enlightenment era and the golden age in Russia. But after Catherine died in 1796, she was succeeded by her son, Paul. He brought Russia into a major coalition war against the new-revolutionary French Republic in 1797.

State budget

[edit]

Russia was in a continuous state of financial crisis. While revenue rose from 9 million rubles in 1724 to 40 million in 1794, expenses grew more rapidly, reaching 49 million in 1794. The budget allocated 46 percent to the military, 20 percent to government economic activities, 12 percent to administration, and nine percent for the Imperial Court in St. Petersburg. The deficit required borrowing, primarily from bankers in Amsterdam; five percent of the budget was allocated to debt payments. Paper money was issued to pay for expensive wars, thus causing inflation. As a result of its spending, Russia developed a large and well-equipped army, a very large and complex bureaucracy, and a court that rivaled those of Paris and London. But the government was living far beyond its means, and 18th-century Russia remained "a poor, backward, overwhelmingly agricultural, and illiterate country".[29]

First half of the 19th century

[edit]In 1801, 4 years after Paul became ruler of Russia, he was killed in the Winter Palace in a coup. Paul was succeeded by a his 27-year-old son, Alexander. Russia was in a state of war with the French Republic under the leadership of the Corsica-born consul Napoleon Bonaparte. After he became the emperor, Napoleon defeated Russia at Austerlitz in 1805, Eylau and Friedland in 1807. After Alexander was defeated in Friedland, he agreed to negotiate and sued for peace with France; the Treaties of Tilsit led to the Franco-Russian alliance against the Coalition and joined the Continental System.[30] By 1812, Russia had occupied many territories in Eastern Europe, holding some of Eastern Galicia from Austria and Bessarabia from the Ottoman Empire;[31] from Northern Europe, it had ceded Finland from the war against weaken Sweden; it also possessed some territory in Caucasus.

Following a dispute with Emperor Alexander I, in 1812, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia. It was catastrophic for France, whose army was decimated during the Russian winter. Although Napoleon's Grande Armée reached Moscow, the Russians' scorched earth strategy prevented the invaders from living off the country. In the harsh and bitter winter, thousands of French troops were ambushed and killed by peasant guerrilla fighters.[32] As Napoleon's forces retreated, Russian troops pursued them into Central and Western Europe and to the gates of Paris. After Russia and its allies defeated Napoleon, Alexander became known as the "saviour of Europe". He presided over the redrawing of the map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna (1815), which ultimately made Alexander the monarch of Congress Poland.[33] The "Holy Alliance" was proclaimed, linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia.

Although the Russian Empire played a leading political role in the next century, thanks to its role in defeating Napoleonic France, its retention of serfdom precluded economic progress to any significant degree. As Western European economic growth accelerated during the Industrial Revolution, Russia began to lag ever farther behind, creating new weaknesses for the Empire seeking to play a role as a great power. Russia's status as a great power concealed the inefficiency of its government, the isolation of its people, and its economic and social backwardness. Following the defeat of Napoleon, Alexander I had been ready to discuss constitutional reforms, but though a few were introduced, no major changes were attempted.[34]

The liberal Alexander I was replaced by his younger brother Nicholas I (1825–1855), who at the beginning of his reign was confronted with an uprising. The background of this revolt lay in the Napoleonic Wars, when a number of well-educated Russian officers travelled in Europe in the course of military campaigns, where their exposure to the liberalism of Western Europe encouraged them to seek change on their return to autocratic Russia. The result was the Decembrist revolt (December 1825), which was the work of a small circle of liberal nobles and army officers who wanted to install Nicholas' brother Constantine as a constitutional monarch. The revolt was easily crushed, but it caused Nicholas to turn away from the modernization program begun by Peter the Great and champion the doctrine of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.[35]

In order to repress further revolts, censorship was intensified, including the constant surveillance of schools and universities. Textbooks were strictly regulated by the government. Police spies were planted everywhere. Would-be revolutionaries were sent off to Siberia – under Nicholas I hundreds of thousands were sent to katorga there.[36] The retaliation for the revolt made "December Fourteenth" a day long remembered by later revolutionary movements.

The question of Russia's direction had been gaining attention ever since Peter the Great's program of modernization. Some favored imitating Western Europe while others were against this and called for a return to the traditions of the past. The latter path was advocated by Slavophiles, who held the "decadent" West in contempt. The Slavophiles were opponents of bureaucracy, who preferred the collectivism of the medieval Russian obshchina or mir over the individualism of the West.[37] More extreme social doctrines were elaborated by such Russian radicals on the left, such as Alexander Herzen, Mikhail Bakunin, and Peter Kropotkin.

Foreign policy (1800–1864)

[edit]After Russian armies liberated the Eastern Georgian Kingdom (allied since the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk) from the Qajar dynasty's occupation of 1802,[citation needed] during the Russo-Persian War (1804–13), they clashed with Persia over control and consolidation of Georgia, and also became involved in the Caucasian War against the Caucasian Imamate. At the conclusion of the war, Persia irrevocably ceded what is now Dagestan, eastern Georgia, and most of Azerbaijan to Russia, under the Treaty of Gulistan.[38] Russia attempted to expand to the southwest, at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, using recently acquired Georgia at its base for its Caucasus and Anatolian front. The late 1820s were successful years militarily. Despite losing almost all recently consolidated territories in the first year of the Russo-Persian War of 1826–28, Russia managed to bring an end to the war with highly favourable terms granted by the Treaty of Turkmenchay, including the formal acquisition of what are now Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iğdır Province.[39] In the 1828–29 Russo-Turkish War, Russia invaded northeastern Anatolia and occupied the strategic Ottoman towns of Erzurum and Gümüşhane and, posing as protector and saviour of the Greek Orthodox population, received extensive support from the region's Pontic Greeks. Following a brief occupation, the Russian imperial army withdrew back into Georgia.[40]

Russian emperors quelled two uprisings in their newly acquired Polish territories: the November Uprising in 1830 and the January Uprising in 1863. In 1863, the Russian autocracy had given the Polish artisans and gentry reason to rebel, by assailing national core values of language, religion, and culture.[41] France, Britain, and Austria tried to intervene in the crisis but were unable to do so. The Russian press and state propaganda used the Polish uprising to justify the need for unity in the Empire.[42] The semi-autonomous polity of Congress Poland subsequently lost its distinctive political and judicial rights, with Russification being imposed on its schools and courts.[43] However, Russification policies in Poland, Finland and among the Germans in the Baltics largely failed and only strengthened political opposition.[42]

Second half of the 19th century

[edit]

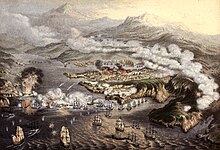

In 1853, the Ottoman Empire, which Russia called the "Sick man of Europe,"[44] behaved more Russian aggression by occupying the Danubian Principalities by declaring war in October.[45][46] Russia's success at Sinope brought the United Kingdom, France, and Italy into the war. The war was fought primarily in the Crimean peninsula, besieged the port city of Sevastopol, and to a lesser extent in the Baltic during the related Åland War, which the British and French navies fought along the coast of Finland, Russia's autonomous duchy, the joint forces blockaded the imperial capital. While Sevastopol fell to the allies after a year of siege. This was the first time Russia was defeated on home soil since 1712.[47] Since playing a major role in the defeat of Napoleon, Russia had been regarded as militarily invincible, but against a coalition of the great powers of Europe, the reverses it suffered on land and sea exposed the weakness of Emperor Nicholas I's regime.

When Emperor Alexander II ascended the throne in 1855, the desire for reform was widespread. A growing humanitarian movement attacked serfdom as inefficient. In 1859, there were more than 23 million serfs in usually poor living conditions. Alexander II decided to abolish serfdom from above, with ample provision for the landowners, rather than wait for it to be abolished from below by revolution.[48]

The Emancipation Reform of 1861, which freed the serfs, was the single most important event in 19th-century Russian history, and the beginning of the end of the landed aristocracy's monopoly on power. The 1860s saw further socio-economic reforms to clarify the position of the Russian government with regard to property rights.[49] Emancipation brought a supply of free labour to the cities, stimulating industry; and the middle class grew in number and influence. However, instead of receiving their lands as a gift, the freed peasants had to pay a special lifetime tax to the government, which in turn paid the landlords a generous price for the land that they had lost. In numerous cases the peasants ended up with relatively small amounts of land. All the property turned over to the peasants was owned collectively by the mir, the village community, which divided the land among the peasants and supervised the various holdings. Although serfdom was abolished, since its abolition was achieved on terms unfavourable to the peasants, revolutionary tensions did not abate. Revolutionaries believed that the newly freed serfs were merely being sold into wage slavery in the onset of the industrial revolution, and that the urban bourgeoisie had effectively replaced the landowners.[50]

Seeking more territories, Russia obtained Priamurye (Outer Manchuria) from weaken Manchu-ruled Qing China, which fought against the Taiping Rebellion. In 1858, the Treaty of Aigun ceded much of the Manchu Homeland, and in 1860, the Treaty of Peking ceded the modern Primorsky Krai, also founded the outpost of future Vladivostok.[51] Meanwhile, Russia was hustled to the United States for 11 million rubles (7.2 million dollars) on its last territory in Russian America, Alyaska (Alaska).[52][53] Initially considered a waste land, gold and petroleum were discovered later.[54]

In the late 1870s, Russia and the Ottoman Empire again clashed in the Balkans. From 1875 to 1877, the Balkan crisis intensified, with rebellions against Ottoman rule by various Slavic nationalities,[55] which the Ottoman Turks had dominated since the 16th century. This was seen as a political risk in Russia, which similarly suppressed its Muslims in Central Asia and Caucasia. Russian nationalist opinion became a major domestic factor with its support for liberating Balkan Christians from Ottoman rule and making Bulgaria and Serbia independent. In early 1877, Russia intervened on behalf of Serbian and Russian volunteer forces,[56] leading to the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78).[44] Within one year, Russian troops were nearing Istanbul and the Ottomans surrendered. Russia's nationalist diplomats and generals persuaded Alexander II to force the Ottomans to sign the Treaty of San Stefano in March 1878, creating an enlarged, independent Bulgaria that stretched into the southwestern Balkans.[56] When Britain threatened to declare war over the terms of the treaty, an exhausted Russia backed down. At the Congress of Berlin in July 1878, Russia agreed to the creation of a smaller Bulgaria, as an autonomous principality inside the Ottoman Empire.[57][58] As a result, Pan-Slavists were left with a legacy of bitterness against Austria-Hungary and Germany for failing to back Russia. Disappointment at the results of the war stimulated revolutionary tensions, and helped Serbia, Romania, and Montenegro gain independence from, and strengthen themselves against, the Ottomans.[59]

Another significant result of the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War in Russia's favour was the acquisition from the Ottomans of the provinces of Batum, Ardahan, and Kars in Transcaucasia, which were transformed into the militarily administered regions of Batum Oblast and Kars Oblast. To replace Muslim refugees who had fled across the new frontier into Ottoman territory, the Russian authorities settled large numbers of Christians from ethnically diverse communities in Kars Oblast, particularly Georgians, Caucasus Greeks, and Armenians, each of whom hoped to achieve protection and advance their own regional ambitions.

Alexander III

[edit]In 1881, Alexander II was assassinated by the Narodnaya Volya, a Nihilist terrorist organization. The throne passed to Alexander III (1881–1894), a reactionary who revived the maxim of "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality" of Nicholas I. A committed Slavophile, Alexander III believed that Russia could be saved from turmoil only by shutting itself off from the subversive influences of Western Europe. During his reign, Russia formed the Franco-Russian Alliance, to contain the growing power of Germany; completed the conquest of Central Asia; and demanded important territorial and commercial concessions from China. The emperor's most influential adviser was Konstantin Pobedonostsev, tutor to Alexander III and his son Nicholas, and procurator of the Holy Synod from 1880 to 1895. Pobedonostsev taught his imperial pupils to fear freedom of speech and the press, as well as dislike democracy, constitutions, and the parliamentary system. Under Pobedonostsev, revolutionaries were persecuted—by the imperial secret police, with thousands being exiled to Siberia—and a policy of Russification was carried out throughout the Empire.[60][61]

Witte's reforms

[edit]Foreign policy (1864–1907)

[edit]Russia had little difficulty expanding to the south, including conquering Turkestan,[62] until Britain became alarmed when Russia threatened Afghanistan, with the implicit threat to India; and decades of diplomatic maneuvering resulted, called the Great Game.[63] That rivalry between the two empires has been considered to have included far-flung territories such as Mongolia and Tibet. The maneuvering largely ended with the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907.[64]

Expansion into the vast stretches of Siberia was slow and expensive, but finally became possible with the building of the Trans-Siberian Railway, 1890 to 1904. This opened up East Asia; and Russian interests focused on Mongolia, Manchuria, and Korea. China was too weak to resist, and was pulled increasingly into the Russian sphere. Russia obtained treaty ports such as Dalian/Port Arthur. In 1900, the Russian Empire invaded Manchuria as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance's intervention against the Boxer Rebellion. Japan strongly opposed Russian expansion, and defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Japan took over Korea, and Manchuria remained a contested area.[65]

Meanwhile, France, looking for allies against Germany after 1871, formed a military alliance in 1894, with large-scale loans to Russia, sales of arms, and warships, as well as diplomatic support. Once Afghanistan was informally partitioned in 1907, Britain, France, and Russia came increasingly close together in opposition to Germany and Austria. They formed the Triple Entente, which played a central role in the First World War. That war broke out when the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with strong German support, tried to suppress Serbian nationalism, with Russia supporting Serbia. The great powers mobilized, and Berlin decided to act before the others were ready to fight, first invading Belgium and France in the west, and then Russia in the east.[66]

League of the Three Emperors

[edit]Early 20th century

[edit]

In 1894, Alexander III was succeeded by his son, Nicholas II, who was committed to retaining the autocracy that his father had left him. Nicholas II proved ineffective as a ruler, and in the end his dynasty was overthrown by revolution.[69] The Industrial Revolution began to show significant influence in Russia, but the country remained rural and poor.

Economic conditions steadily improved after 1890, thanks to new crops such as sugar beets, and new access to railway transportation. Total grain production increased, as well as exports, even with rising domestic demand from population growth. As a result, there was a slow improvement in the living standards of Russian peasants in the Empire's last two decades before 1914. Recent research into the physical stature of Army recruits shows they were bigger and stronger. There were regional variations, with more poverty in the heavily populated central black earth region; and there were temporary downturns in 1891–93 and 1905–1908.[70]

On the political right, the reactionary elements of the aristocracy strongly favored the large landholders, who, however, were slowly selling their land to the peasants through the Peasants' Land Bank. The Octobrist party was a conservative force, with a base of landowners and businessmen. They accepted land reform but insisted that property owners be fully paid. They favored far-reaching reforms, and hoped the landlord class would fade away, while agreeing they should be paid for their land. Liberal elements among industrial capitalists and nobility, who believed in peaceful social reform and a constitutional monarchy, formed the Constitutional Democratic Party or Kadets.[71]

On the left, the Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) and the Marxist Social Democrats wanted to expropriate the land, without payment, but debated whether to distribute the land among the peasants (the Narodnik solution), or to put it into collective local ownership.[72] The Socialist Revolutionaries also differed from the Social Democrats in that the SRs believed a revolution must rely on urban workers, not the peasantry.[73]

In 1903, at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, in London, the party split into two wings: the gradualist Mensheviks and the more radical Bolsheviks. The Mensheviks believed that the Russian working class was insufficiently developed and that socialism could be achieved only after a period of bourgeois democratic rule. They thus tended to ally themselves with the forces of bourgeois liberalism. The Bolsheviks, under Vladimir Lenin, supported the idea of forming a small elite of professional revolutionists, subject to strong party discipline, to act as the vanguard of the proletariat, in order to seize power by force.[74]

Defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) was a major blow to the tsarist regime and further increased the potential for unrest. In January 1905, an incident known as "Bloody Sunday" occurred when Father Georgy Gapon led an enormous crowd to the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to present a petition to the emperor. When the procession reached the palace, soldiers opened fire on the crowd, killing hundreds. The Russian masses were so furious over the massacre that a general strike was declared, which demanded a democratic republic. This marked the beginning of the Revolution of 1905. Soviets (councils of workers) appeared in most cities to direct revolutionary activity. Russia was paralyzed, and the government was desperate.[75]

In October 1905, Nicholas reluctantly issued the October Manifesto, which conceded the creation of a national Duma (legislature) to be called without delay. The right to vote was extended and no law was to become final without confirmation by the Duma. The moderate groups were satisfied, but the socialists rejected the concessions as insufficient and tried to organise new strikes. By the end of 1905, there was disunity among the reformers, and the emperor's position was strengthened for the time being.

War on the Japaneses

[edit]The first revolution

[edit]Stolypin's era

[edit]War, revolution, and collapse

[edit]Origins of causes

[edit]Russia, along with France and Britain, was a member of the Entente in antecedent to World War I; these three powers were formed up in response of Germany's growing diadem,[76] one of the member of the Triple Alliance, besides Austria-Hungary and Italy. Previously, Saint Petersburg and Paris, along with London, were calumniators in the Crimean War. The relations with Britain were in disquietude from the Great Game in Central Asia until 1907, when both agreed to end the influential war and joined to anti the new rising power of Germany.[77] Russia and France's relations remained isolated before the 1890s when both sides agreed to ally when peace was threatened.[78] France also granted loans for building infrastructure, especially railways.[79]

The relations between Russia and the Triple Alliance, especially Germany and Austria, were like those of the League of the Three Emperors. Russia's relations with Germany were deteriorating,[80] and tensions over the Eastern question had reached a breaking point with Austria.[81] In 1910, relations between Saint Petersburg and Vienna were tense during the Balkan War.[82]

The assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, raised Europe's tensions, which led to the confrontation between Austria and Russia.[83] Serbia rejected an Austrian ultimatum that demanded an obligation for the heir's death, and Austria cut all diplomatic ties and declared war on 28 July 1914. Russia averted Serbia because it being a compeer Slavic state, and two days later, it ordered the mobilisation to bestow the loyalty to the Orthodox Church, not just for a similar slavic nation.[84] Elicit in Germany demanded an ultimatum to abandon the congeries about its troops, which led to in a status of war four days later.

Declaration of War

[edit]

As a result of Austria's declaration of war on Serbia, Emperor Nicholas II ordered the mobilisation of 4.9 million men. Germany, the Austria's ally, saw the call to arms as a threat; when Russia mustered its troops, Germany affirmed the state of "imminent danger of War", followed by the declaration of war on 2 August 1914.[85] The Russians were imbued with patriotic earnestness and Germanophobia sentiment, including the name of the capital, Saint Petersburg, which sounded too German for the sake of words Sankt- and -burg; and was thus renamed to Petrograd for more Russianised.[86]

The Russian ingress of the First World War was followed by France, which both colleagued in 1892, and feared the rise of Germany as the new power.[87] prompted Berlin to devise the Schlieffen Plan, which first eliminated France via nonaligned Belgium before moving east to inflict on Russia, whose massive army was much slower to mobilise.[88]

Theatres

[edit]German theatre

[edit]

By August 1914, Russia had invaded the German province of East Prussia, ending with a humiliating defeat at Tannenberg, owing to the message sent without coding,[89] causing the destruction of the entire second army. Russia suffered a massive defeat at the Masurian Lakes twice, the first ending with a hundred thousand casualties;[90] and the second suffering 200,000.[91] By October, the German Ninth Army was near Warsaw, and the newly-formed Tenth Army had retreated from the frontier in East Prussia. Grand Duke Nicholas, the Russian commander-in-chief, now had the order to invade Silesia with his Fifth, Fourth, and Ninth armies.[92] The Ninth Army, led by Mackensen, retreated from the frontline in Galicia and concentrated between the cities of Posen and Thorn. The advance took place in Lodz on 11 November, motivated the first and second armies to be severely mauled, and the second army was nearly surrounded on 17 November.

Exhausted Russian troops began to withdraw from Russian-held Poland, allowing the Germans who captured many cities, including the Kingdom's capital Warsaw on 5 August 1915.[93] The prominent "Attack of the Dead Men" occurred in Osovets Fortress on 6 August, where German troops hurled poisonous gases into the fort, but narrowly surviving Russian combatants repulsed the German attack like zombies. In the same month, the emperor dismissed Grand Duke Nicholas and took charge in command,[94] this was a turning point for the Russian army and the beginning of the worst disaster.[95] The Germans continued pushing the front until they were halted in the line from Riga to Tarnopol.[96] Russia lost the entire territory of Poland and Lithuania,[97] part of the Baltic states and Grodno, and partly of Volhynia and Podolia in Ukraine; the front with Germany was stable until 1917.

Austrian theatre

[edit]Austria went to war with Russia on 6 August. The Russians started to invade Galicia, held by Austrian Cisleithania on 20 August, and annihilated the Austrian Army at Lemberg, leading to the occupation of Galicia.[98] While the fortress of Premissel was besieged, the first attempt to capture the fortress failed, but the second attempt seized the redoubt in March 1915.[99] On 2 May, the Russian army was broken in the front and retreated from the line stretched from Gorlice to Tarnów by joint Austro-German forces and lost Premissel.

On 4 June 1916, General Aleksei Brusilov carried out an offensive to the front by targeting Kovel. His offensive was an eminence, taking 76,000 prisoners from the main attack and 1,500 from the Austrian bridgehead. But the offensive was halted by inadequate ammunition and a lack of supplies.[100] The name-sake offensive was the most successful allied strike of World War I,[101] but the slaughter of many casualties (approximately one million men) forced the Russian forces not to rebuild or launch any further attacks.

Turkish theatre

[edit]On 29 October 1914, a prelude to the Russo-Turkish front, the Turkish fleet, with the German support, began to raid Russian coastal cities in Odessa, Sevastopol, Novorossiysk, Feodosia, Kerch, and Yalta.[102] Triggered Russia to join the war on 2 November.[103] The Russians, led by Baltic German General Georgy Bergmann, opened the front by crossing the frontier but failed to capture Kyopryukyoy. In December, Russia obtained success at Sarikamish, where the Russian General Yudenich routed Enver Pasha in the battle.[104]

Homefront

[edit]

By the middle of 1915, the impact of the war was demoralizing. Food and fuel were in short supply, casualties were increasing, and inflation was mounting. Strikes rose among low-paid factory workers, and there were reports that peasants, who wanted reforms of land ownership, were restless. The emperor eventually decided to take personal command of the army and moved to the front, leaving his wife, the Empress Alexandra, in charge in the capital. She fell under the spell of a monk, Grigori Rasputin (1869–1916). His assassination in late 1916 by a clique of nobles could not restore the emperor's lost prestige.[105]

Fate of the Imperial rule and the family

[edit]On 3 March 1917, International Women's Day, a strike was organized at a factory in the capital, followed by thousands of people took to the streets in Petrograd to protest aliment shortages. A day later, protestors rose to two hundred thousand who cried, "Down with the Autocracy" and "Down with the War." Eighty thousand Russian troops, half of the delegations to restore order, had gone on strike and refused the high officers' orders.[106] Any symbols of Russian imperialism were destroyed and burned. The capital was out of control of the protest and strife.[107]

In the city of Pskov, 262 kilometres (163 mi) southwest from the capital. Many generals and politicians advised the Emperor to abdicate in favour of Tsarevich; Nicholas accepted, but he bequeathed the throne to Grand Duke Mikhail.[108] The Tsarist system was fully overthrowned.

On 2 March 1917, Nicholas II abdicated, and soon, On the night of July 16–17, 1918, Nicholas Romanov, Alexandra Feodorovna, his sons, and servants were woken by Yakov Yurovsky in Ipatiev House. He claimed to have fled the city because of riots and was taken to the basement. When the family arrived at the site of the execution, the guard commissar announced the family members must be executed. When Nicholas heard the order, he answered, "What?"[109] After Nicholas answered, the Tsar and his family, including his retainers and servants, were shot until dead.

Territory

[edit]

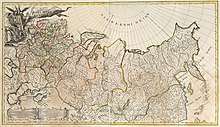

By the end of the 19th century the area of the empire was about 22,400,000 square kilometers (8,600,000 sq mi), or almost 1⁄6 of the Earth's landmass; its only rival in size at the time was the British Empire. The majority of the population lived in European Russia. More than 100 different ethnic groups lived in the Russian Empire, with ethnic Russians composing about 45% of the population.[110]

Geography

[edit]The administrative boundaries of European Russia, apart from Finland and its portion of Poland, coincided approximately with the natural limits of the East-European plains. To the north was the Arctic Ocean. Novaya Zemlya and the Kolguyev and Vaygach Islands were considered part of European Russia, but the Kara Sea was part of Siberia. To the east were the Asiatic territories of the Empire: Siberia and the Kyrgyz steppes, from both of which it was separated by the Ural Mountains, the Ural River, and the Caspian Sea — the administrative boundary, however, partly extended into Asia on the Siberian slope of the Urals. To the south, were the Black Sea and the Caucasus, being separated from the latter by the Manych River depression, which in post-Pliocene times connected the Sea of Azov with the Caspian. The western boundary was purely arbitrary: it crossed the Kola Peninsula from the Varangerfjord to the Gulf of Bothnia. It then ran to the Curonian Lagoon in the southern Baltic Sea, and then to the mouth of the Danube, taking a great circular sweep to the west to embrace east-central Poland, and separating Russia from Prussia, Austrian Galicia, and Romania.

An important feature of Russia is its few free outlets to the open sea, outside the ice-bound shores of the Arctic Ocean. The deep indentations of the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland were surrounded by what is ethnically Finnish territory, and it is only at the very head of the latter gulf that the Russians had taken firm foothold by erecting their capital at the mouth of the Neva River. The Gulf of Riga and the Baltic belong also to territory that was not inhabited by Slavs, but by Baltic and Finnic peoples, and by Germans. The east coast of the Black Sea belonged to Transcaucasia, a great chain of mountains separating it from Russia. But even this sheet of water is an inland sea, the only outlet of which, the Bosphorus, was in foreign hands, while the Caspian Sea, an immense shallow lake, mostly bordered by deserts, possessed more importance as a link between Russia and its Asiatic settlements than as a channel for intercourse with other countries.

Territorial development

[edit]In addition to almost the entire territory of modern Russia,[h] prior to 1917 the Russian Empire included most of Dnieper Ukraine, Belarus, Bessarabia, the Grand Duchy of Finland, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Central Asian states of Russian Turkestan, most of the Baltic governorates, a significant part of Poland, and the former Ottoman provinces of Ardahan, Artvin, Iğdır, Kars, and the northeastern part of Erzurum Provinces.

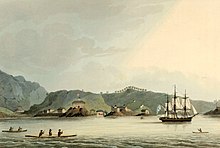

Between 1742 and 1867, the Russian-American Company administered Alaska as a colony. The company also established settlements in Hawaii, including Fort Elizabeth (1817), and as far south in North America as Fort Ross Colony (established in 1812) in Sonoma County, California just north of San Francisco. Both Fort Ross and the Russian River in California got their names from Russian settlers, who had staked claims in a region claimed until 1821 by the Spanish as part of New Spain.

Following the Swedish defeat in the Finnish War of 1808–1809 and the signing of the Treaty of Fredrikshamn on 17 September 1809, the eastern half of Sweden, the area that then became Finland, was incorporated into the Russian Empire as an autonomous grand duchy. The emperor eventually ended up ruling Finland as a semi-constitutional monarch through the Governor-General of Finland and a native Senate appointed by him. The Emperor never explicitly recognized Finland as a constitutional state in its own right, although his Finnish subjects came to consider the grand duchy as such.

In the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War (1806–12), and the ensuing Treaty of Bucharest (1812), the eastern parts of the Principality of Moldavia, an Ottoman vassal state, along with some areas formerly under direct Ottoman rule, came under the rule of the Empire. This area (Bessarabia) was among the Russian Empire's last territorial acquisitions in Europe. At the Congress of Vienna (1815), Russia gained sovereignty over Congress Poland, which on paper was an autonomous Kingdom in personal union with Russia. However, this autonomy was eroded after an uprising in 1831, and was finally abolished in 1867.

Saint Petersburg gradually extended and consolidated its control over the Caucasus in the course of the 19th century, at the expense of Persia through the Russo-Persian Wars of 1804–13 and 1826–28 and the respectively ensuing treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay,[111] as well as through the Caucasian War (1817–1864).

The Russian Empire expanded its influence and possessions in Central Asia, especially in the later 19th century, conquering much of Russian Turkestan in 1865 and continuing to add territory as late as 1885.

Newly discovered Arctic islands became part of the Russian Empire: the New Siberian Islands from the early 18th century; Severnaya Zemlya ("Emperor Nicholas II Land") first mapped and claimed as late as 1913.

During World War I, Russia briefly occupied a small part of East Prussia, then a part of Germany; a significant portion of Austrian Galicia; and significant portions of Ottoman Armenia. While the modern Russian Federation currently controls the Kaliningrad Oblast, which comprised the northern part of East Prussia, this differs from the area captured by the Empire in 1914, though there was some overlap: Gusev (Gumbinnen in German) was the site of the initial Russian victory.

Imperial territories

[edit]

According to the 1st article of the Organic Law, the Russian Empire was one indivisible state. In addition, the 26th article stated that "With the Imperial Russian throne are indivisible the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Principality of Finland". Relations with the Grand Principality of Finland were also regulated by the 2nd article, "The Grand Principality of Finland, constituted an indivisible part of the Russian state, in its internal affairs governed by special regulations at the base of special laws", and by the law of 10 June 1910.

Between 1744 and 1867, the empire also controlled Russian America. With the exception of this territory – modern-day Alaska – the Russian Empire was a contiguous mass of land spanning Europe and Asia. In this it differed from contemporary colonial-style empires. The result of this was that, while the British and French empires declined in the 20th century, a large portion of the Russian Empire's territory remained together, first within the Soviet Union, and after 1991 in the still-smaller Russian Federation.

Furthermore, the empire at times controlled concession territories, notably the Kwantung Leased Territory and the Chinese Eastern Railway, both conceded by Qing China, as well as a concession in Tianjin. See for these periods of extraterritorial control the empire of Japan–Russian Empire relations.

In 1815, Dr. Schäffer, a Russian entrepreneur, went to Kauai and negotiated a treaty of protection with the island's governor Kaumualii, vassal of King Kamehameha I of Hawaii, but the Russian emperor refused to ratify the treaty. See also Orthodox Church in Hawaii and Russian Fort Elizabeth.

In 1889, a Russian adventurer, Nikolay Ivanovitch Achinov, tried to establish a Russian colony in Africa, Sagallo, situated on the Gulf of Tadjoura in present-day Djibouti. However this attempt angered the French, who dispatched two gunboats against the colony. After a brief resistance, the colony surrendered and the Russian settlers were deported to Odesa.

Government and administration

[edit]| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

From its initial creation until the 1905 Revolution, the Russian Empire was controlled by its tsar/emperor as an absolute monarch, under a system of tsarist autocracy. After the Revolution of 1905, Russia developed a new type of government, which became difficult to categorize. In the Almanach de Gotha for 1910, Russia was described as "a constitutional monarchy under an autocratic Tsar". This contradiction in terms demonstrated the difficulty of precisely defining the system, transitional and sui generis, established in the Russian Empire after October 1905. Before this date, the fundamental laws of Russia described the power of the emperor as "autocratic and unlimited". After October 1905, while the imperial style was still "Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias", the fundamental laws were changed by removing the word unlimited. While the emperor retained many of his old prerogatives, including an absolute veto over all legislation, he equally agreed to the establishment of an elected parliament, without whose consent no laws were to be enacted in Russia. Not that the regime in Russia had become in any true sense constitutional, far less parliamentary. But the "unlimited autocracy" had given way to a "self-limited autocracy". Whether this autocracy was to be permanently limited by the new changes, or only at the continuing discretion of the autocrat, became a subject of heated controversy between conflicting parties in the state. Provisionally, then, the Russian governmental system may perhaps be best defined as "a limited monarchy under an autocratic emperor".

Conservatism was the ideology of most of the Russian leadership, albeit with some reformist activities from time to time. The structure of conservative thought was based upon anti-rationalism of the intellectuals, religiosity rooted in the Russian Orthodox Church, traditionalism rooted in the landed estates worked by serfs, and militarism rooted in the army officer corps.[112] Regarding irrationality, Russia avoided the full force of the European Enlightenment, which gave priority to rationalism, preferring the romanticism of an idealized nation state that reflected the beliefs, values, and behavior of the distinctive people.[113] The distinctly liberal notion of "progress" was replaced by a conservative notion of modernization based on the incorporation of modern technology to serve the established system. The promise of modernization in the service of autocracy frightened the socialist intellectual Alexander Herzen, who warned of a Russia governed by "Genghis Khan with a telegraph".[114]

Tsar/Emperor

[edit]

Peter the Great changed his title from tsar in 1721, when he was declared Emperor of all Russia. While later rulers did not discard the new title, the ruler of Russia was commonly known as tsar or tsaritsa until the imperial system was abolished during the February Revolution of 1917. Prior to the issuance of the October Manifesto, the emperor ruled as an absolute monarch, subject to only two limitations on his authority, both of which were intended to protect the existing system: the Emperor and his consort must both belong to the Russian Orthodox Church, and he must obey the (Pauline Laws) of succession established by Paul I. Beyond this, the power of the Russian autocrat was virtually limitless.

On 17 October 1905, the situation changed: the ruler voluntarily limited his legislative power by decreeing that no measure was to become law without the consent of the Imperial Duma, a freely elected national assembly established by the Organic Law issued on 28 April 1906. However, he retained the right to disband the newly established Duma, and he exercised this right more than once. He also retained an absolute veto over all legislation, and only he could initiate any changes to the Organic Law itself. His ministers were responsible solely to him, and not to the Duma or any other authority, which could question but not remove them. Thus, while the emperor's personal powers were limited in scope after 28 April 1906, they remained formidable.

Imperial Council

[edit]

Under Russia's revised Fundamental Law of 20 February 1906, the Council of the Empire was associated with the Duma as a legislative Upper House; from this time the legislative power was exercised normally by the Emperor only in concert with the two chambers.[115] The Council of the Empire, or Imperial Council, as reconstituted for this purpose, consisted of 196 members, of whom 98 were nominated by the emperor, while 98 were elective. The ministers, also nominated, were ex officio members. Of the elected members, 3 were returned by the "black" clergy (the monks), 3 by the "white" clergy (secular), 18 by the corporations of nobles, 6 by the academy of sciences and the universities, 6 by the chambers of commerce, 6 by the industrial councils, 34 by local governmental zemstvos, 16 by local governments having no zemstvos, and 6 by Poland. As a legislative body the powers of the council were coordinate with those of the Duma; in practice, however, it has seldom if ever initiated legislation.

State Duma

[edit]The Duma of the Empire or Imperial Duma (Gosudarstvennaya Duma), which formed the lower house of the Russian parliament, consisted (since the ukaz of 2 June 1907) of 442 members, elected by an exceedingly complicated process. The membership was manipulated as to secure an overwhelming majority of the wealthy (especially the landed classes) and also for the representatives of the Russian peoples at the expense of the subject nations. Each province of the Empire, except Central Asia, returned a certain number of members; added to which were those returned by several large cities. The members of the Duma were chosen by electoral colleges and these, in their turn, were elected by assemblies of the three classes: landed proprietors, citizens, and peasants. In these assemblies the wealthiest proprietors sat in person while the lesser proprietors were represented by delegates. The urban population was divided into two categories according to taxable wealth and elected delegates directly to the college of the governorates. The peasants were represented by delegates selected by the regional subdivisions called volosts. Workmen were treated in a special manner, with every industrial concern employing fifty hands electing one or more delegates to the electoral college.

In the college itself, the voting for the Duma was by secret ballot and a simple majority carried the day. Since the majority consisted of conservative elements (the landowners and urban delegates), the progressives had little chance of representation at all, save for the curious provision that one member at least in each government was to be chosen from each of the five classes represented in the college. That the Duma had any radical elements was mainly due to the peculiar franchise enjoyed by the seven largest towns — Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Kyiv, Odesa, Riga, and the Polish cities of Warsaw and Łódź. These elected their delegates to the Duma directly, and though their votes were divided (on the basis of taxable property) in such a way as to give the advantage to wealth, each returned the same number of delegates.

Council of Ministers

[edit]In 1905, a Council of Ministers (Sovyet Ministrov) was created, under a minister president, the first appearance of a prime minister in Russia. This council consisted of all the ministers and of the heads of other principal departments. The ministries were as follows:

- Ministry of the Imperial Court

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs;

- Ministry of War;

- Ministry of the Navy;

- Ministry of Finance;

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry (created in 1905);

- Ministry of Internal Affairs (including police, health, censorship and press, posts and telegraphs, foreign religions, statistics);

- Ministry of Agriculture and State Assets;

- Ministry of ways of Communications;

- Ministry of Justice;

- Ministry of National Enlightenment.

Most Holy Synod

[edit]

The Most Holy Synod (established in 1721) was the supreme organ of government of the Orthodox Church in Russia. It was presided over by a lay procurator, representing the Emperor, and consisted of the three metropolitans of Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Kiev, the archbishop of Georgia, and a number of bishops sitting in rotation.

Senate

[edit]The Senate (Pravitelstvuyushchi Senat, i.e. directing or governing senate), originally established during the government reform of Peter I, consisted of members nominated by the emperor. Its wide variety of functions were carried out by the different departments into which it was divided. It was the supreme court of cassation; an audit office; a high court of justice for all political offences; and one of its departments fulfilled the functions of a heralds' college. It also had supreme jurisdiction in all disputes arising out of the administration of the Empire, notably in differences between representatives of the central power and the elected organs of local self-government. Lastly, it promulgated new laws, a function which theoretically gave it a power akin to that of the Supreme Court of the United States, of rejecting measures not in accordance with fundamental laws.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

As of 1914, Russia was divided into 81 governorates (guberniyas), 20 oblasts, and 1 okrug. Vassals and protectorates of the Russian Empire included the Emirate of Bukhara, the Khanate of Khiva, and, after 1914, Tuva (Uriankhai). Of these, 11 Governorates, 17 oblasts, and 1 okrug (Sakhalin) belonged to Asian Russia. Of the rest, 8 Governorates were in Finland and 10 in Congress Poland. European Russia thus embraced 59 governorates and 1 oblast (that of the Don). The Don Oblast was under the direct jurisdiction of the ministry of war; the rest each had a governor and deputy-governor, the latter presiding over the administrative council. In addition, there were governors-general, generally placed over several governorates and armed with more extensive powers, usually including the command of the troops within the limits of their jurisdiction. In 1906, there were governors-general in Finland, Warsaw, Vilna, Kiev, Moscow, and Riga. The larger cities (Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, Sevastopol, Kerch, Nikolayev, and Rostov) had administrative systems of their own, independent of the governorates; in these the chief of police acted as governor.

Judicial system

[edit]The judicial system of the Russian Empire was established by the statute of 20 November 1864 of Alexander II. This system – based partly on English and French law – was predicated on the separation of judicial and administrative functions, the independence of the judges and courts, public trials and oral procedure, and the equality of all classes before the law. Moreover, a democratic element was introduced by the adoption of the jury system and the election of judges. This system was disliked by the bureaucracy, due to its putting the administration of justice outside of the executive sphere. During the latter years of Alexander II and the reign of Alexander III, power that had been given was gradually taken back, and that take back was fully reversed by the third Duma after the 1905 Revolution.[i]

The system established by the law of 1864 had two wholly separate tribunals, each having their own courts of appeal and coming in contact with each other only in the Senate, which acted as the supreme court of cassation. The first tribunal, based on the English model, were the courts of the elected justices of the peace, with jurisdiction over petty causes, whether civil or criminal; the second, based on the French model, were the ordinary tribunals of nominated judges, sitting with or without a jury to hear important cases.

Local administration

[edit]Alongside the local organs of the central government in Russia there are three classes of local elected bodies charged with administrative functions:

- the peasant assemblies in the mirs and the volosts;

- the zemstvos in the 34 governorates of Russia;

- the municipal dumas.

Municipal dumas

[edit]

Since 1870, the municipalities in European Russia had institutions like those of the zemstvos. All owners of houses, tax-paying merchants, artisans, and workmen were enrolled on lists, in descending order according to their assessed wealth. The total valuation was then divided into three equal parts, representing three groups of electors very unequal in number, each of which would elect an equal number of delegates to the municipal duma. The executive was in the hands of an elected mayor and an uprava, which consisted of several members elected by the municipal duma. Under Alexander III, however, by-laws promulgated in 1892 and 1894, the municipal dumas were subordinated to the governors in the same way as the zemstvos. In 1894, municipal institutions, with still more restricted powers, were granted to several towns in Siberia, and in 1895 to some in the Caucasus.

Baltic provinces

[edit]The formerly Swedish-controlled Baltic provinces of Livonia and Estonia and later Duchy of Courland, a vassal of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, were incorporated into the Russian Empire after the defeat of Sweden in the Great Northern War. Under the Treaty of Nystad of 1721, the Baltic German nobility retained considerable powers of self-government and numerous privileges in matters affecting education, police, and the local administration of justice. After 167 years of German language administration and education, in 1888 and 1889 laws were passed transferring administration of the police and manorial justice from Baltic German control to officials of the central government. About the same time, a process of Russification was being carried out in the same provinces, in all departments of administration, in the higher schools, and in the Imperial University of Dorpat, the name of which was altered to Yuriev. In 1893, district committees for the management of the peasants' affairs, similar to those in purely Russian governments, were introduced into this part of the Empire.

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]Much of Russia's expansion occurred in the 17th century, culminating in the first Russian colonization of the Pacific, the Russo-Polish War (1654–67), which led to the incorporation of left-bank Ukraine, and the Russian conquest of Siberia. Poland was partitioned by its three neighbours in the 1772–1815 era, with much of its land and population being taken under Russian rule. Most of the empire's growth in the 19th-century came from gaining territory in central and eastern Asia south of Siberia.[116] By 1795, after the Partitions of Poland, Russia became the most populous state in Europe, ahead of France.

| Year | Population of Russia (millions)[117][118] | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1720 | 15.5 | includes new Baltic & Polish territories |

| 1795 | 37.6 | includes part of Poland |

| 1812 | 42.8 | includes Finland |

| 1816 | 73.0 | includes Congress Poland, Bessarabia |

| 1897 | 125.6 | Russian Empire Census[j] |

| 1914 | 164.0 | includes new Asian territories |

Largest cities

[edit]| No. | English name | Russian name | Other names | Current country | Population in 1897 (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Saint Petersburg | Санкт-Петербургъ | Russia | 1.265 | |

| 2. | Moscow | Москва | Russia | 1.039 | |

| 3. | Warsaw | Варшава | Warszawa | Poland | 0.684 |

| 4. | Odessa | Одесса | Одеса | Ukraine | 0.404 |

| 5. | Lodz | Лодзь | Łódź | Poland | 0.314 |

| 6. | Riga | Рига | Rīga, Rīgõ | Latvia | 0.282 |

| 7. | Kiev | Кіевъ | Київ | Ukraine | 0.248 |

| 8. | Kharkov | Харьковъ | Харків | Ukraine | 0.174 |

| 9. | Tiflis | Тифлисъ | ტფილისი | Georgia | 0.160 |

| 10. | Tashkent | Ташкентъ | Toshkent, Тошкент | Uzbekistan | 0.156 |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | Russian Empire[119] | European Russia | Poland | Caucasus | Siberia | Central Asia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Russian Orthodox | 87,123,604 | 69.34 | 76,344,717 | 81.70 | 607,591 | 6.46 | 4,589,285 | 49.40 | 4,940,379 | 85.79 | 641,632 | 8.28 |

| Muslims | 13,906,972 | 11.1 | 3,572,617 | 3.82 | 4,903 | 0.05 | 3,206,224 | 34.52 | 126,574 | 2.20 | 6,996,654 | 90.32 |

| Roman Catholics | 11,467,994 | 9.1 | 4,341,930 | 4.65 | 7,031,949 | 74.79 | 45,378 | 0.49 | 35,152 | 0.61 | 13,585 | 0.18 |

| Rabbinic Jews | 5,215,805 | 4.2% | 3,789,448 | 4.06 | 1,321,100 | 14.05 | 56,783 | 0.61 | 34,792 | 0.60 | 13,682 | 0.18 |

| Lutherans[k] | 3,572,653 | 2.8 | 3,079,276 | 3.30 | 414,769 | 4.41 | 54,654 | 0.59 | 15,372 | 0.27 | 8,582 | 0.11 |

| Old Believers | 2,204,596 | 1.8 | 1,754,860 | 1.88 | 9,423 | 0.10 | 135,627 | 1.46 | 239,642 | 4.16 | 65,044 | 0.84 |

| Armenian Apostolics | 1,179,241 | 0.9 | 47,884 | 0.05 | 221 | 0.00 | 1,125,795 | 12.12 | 503 | 0.01 | 4,838 | 0.06 |

| Buddhists (Minor) and Lamaists (Minor) | 433,863 | 0.4 | 170,006 | 0.18 | 117 | 0.00 | 14,923 | 0.16 | 247,566 | 4.30 | 1,251 | 0.02 |

| Other non-Christian religions | 285,321 | 0.2 | 149,568 | 0.16 | 105 | 0.00 | 17,568 | 0.19 | 117,778 | 2.05 | 302 | 0.00 |

| Reformed | 85,400 | 0.1 | 77,321 | 0.08 | 5,502 | 0.06 | 1,992 | 0.02 | 232 | 0.00 | 353 | 0.00 |

| Mennonites | 66,564 | 0.1 | 63,511 | 0.07 | 758 | 0.01 | 1,680 | 0.02 | 34 | 0.00 | 581 | 0.01 |

| Armenian Catholics | 38,840 | 0.0 | 2,235 | 0.00 | 417 | 0.00 | 36,114 | 0.39 | 44 | 0.00 | 30 | 0.00 |

| Baptists | 38,139 | 0.0 | 31,193 | 0.03 | 3,993 | 0.04 | 2,338 | 0.03 | 543 | 0.01 | 72 | 0.00 |

| Karaite Jews | 12,894 | 0.0 | 12,292 | 0.01 | 225 | 0.00 | 204 | 0.00 | 128 | 0.00 | 45 | 0.00 |

| Anglicans | 4,183 | 0.0 | 3,885 | 0.00 | 194 | 0.00 | 70 | 0.00 | 25 | 0.00 | 9 | 0.00 |

| Other Christian religions | 3,952 | 0.0 | 2,121 | 0.00 | 986 | 0.01 | 729 | 0.01 | 58 | 0.00 | 58 | 0.00 |

| TOTAL | 125,640,021 | 100.00 | 93,442,864 | 100.00 | 9,402,253 | 100.00 | 9,289,364 | 100.00 | 5,758,822 | 100.00 | 7,746,718 | 100.00 |

Economy

[edit]

Before the liberation of the serfs in 1861, Russia's economy mainly depended on agriculture.[120] By the census of 1897, 95 per cent of the Russian population lived in the countryside.[121] Nicholas I attempted to modernise his country, and have it not be so dependant on a single economic sector.[122] During the reign of Alexander III, many reforms occurred. The Peasants' Land Bank was founded in 1883 to provide loans for Russian peasants, both as individuals and in communes. The Nobles' Land Bank, in 1885, made loans at nominal interest rates to the landed nobility. The poll tax was abolished in 1886.[123]

When Ivan Vyshnegradsky was appointed as the new minister of finance in 1886, he increased the pressure on peasants by increasing taxes on land and prescribing how they harvested grain. These policies led to the massive famine that lasted from 1891 to 1892, with ten thousand perishing from starvation. Vyshnegradsky was succeeded by Count Sergei Witte in 1892. Witte began by raising revenues through a monopoly on alcohol, which brought in 300 million rubles 1894. These reforms returned the peasants to essentially being serfs again.[124] In 1900, a bloated peasant class (also known as kulak) had emerged, representing less than 20 per cent of the population, who were characterised by owning some of their land, machine, and livestock.[125] An income tax was introduced in 1916.

Agriculture

[edit]Russia had a long-standing economic bargain on fundamental agriculture on large estates, which was worked by Russian peasants (also known as serfs), who didn't get any rights from slave masters under the system of "barshchina."[l] Another system was called "obrok,"[m] in which serfs worked in exchange for cash or goods from the master, allowing them to work outside the estate.[126] This system was based on the legal code called "Sobornoye Ulozheniye," which descended from the Tsardom Era used by Alexis I.

Serfs lived in deplorable conditions, working in the fields for nearly seven days a week and being exiled to the harsh land of Siberia or sent to military service. Owners had the right to sell slaves, depending on whether they were targeting land or accused (i.e., had escaped from working). Children of serfs recieved less education. These slaves were heavily taxed, making them the poorest in any Russians. In 1861, Emperor Alexander II saw serfs as a problem that dragged Russia into being obsolete, so he liberated 23 million serfs to become free,[127] but they remained indigent throughout the former enslaved population despite their rights. The zemstvo system was introduced in 1865 as a rural assembly with administrative authority over the local population, including education and welfare, which ex-slaves were unable to acquire.

From 1891 to 1892, peasants were faced with new policies carried out by Ivan Vyshnegradsky, causing the famine and disease that took the lives of four hundred thousand people,[128][129] especially in the Volga region, eliciting the greatest decline in grain production.[130]

Mining and heavy industry

[edit]

| Ural Region | Southern Region | Caucasus | Siberia | Kingdom of Poland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | 21% | – | – | 88.2% | - |

| Platinum | 100% | – | – | – | – |

| Silver | 36% | – | 24.3% | 29.3% | – |

| Lead | 5.8% | – | 92% | – | 0.9% |

| Zinc | – | – | 25.2% | – | 74.8% |

| Copper | 54.9% | – | 30.2% | 14.9% | – |

| Pig Iron | 19.4% | 67.7% | – | – | 9.3% |

| Iron and Steel | 17.3% | 36.2% | – | – | 10.8% |

| Manganese | 0.3% | 29.2% | 70.3% | – | – |

| Coal | 3.4% | 67.3% | – | 5.8% | 22.3% |

| Petroleum | – | – | 96% | – | – |

Military

[edit]

The military of the Russian Empire consisted of the Imperial Russian Army and the Imperial Russian Navy. The poor performance during the Crimean War, 1853–56, caused great soul-searching and resulted in proposals for reform. However, the Russian forces fell further behind the technology, training, and organization of the German, French, and particularly the British militaries.[131]

The army performed poorly in World War I and became a center of unrest and revolutionary activity. The events of the February Revolution and the fierce political struggles inside army units led to irreversible disintegration.[132]

The Russian Navy was founded by Peter the Great in 1696 during his journey.[133]

See also

[edit]- Expansion of Russia (1500–1800)

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

- List of Russian monarchs

- Russian conquest of Afghanistan

- Russian conquest of the Caucasus

- Russian imperialism

Notes

[edit]- ^ After reformed Russian orthography in 1918, in the modern one is spelled Российская Империя

- ^ Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1829–56.

- ^ In 1914, this city was renamed Petrograd to reflect anti-German sentiments from its entry into the war as Allies.[1] which remained until renamed again as Leningrad in 1924.

- ^ As Chairman of the Committee of Ministers.

- ^ As Prime Minister.

- ^ Russian: Россійская Имперія, romanized: Rossiyskaya Imperiya, IPA: [rɐˈsʲijskəjə ɪmˈpʲerʲɪjə] ; also Российская Империя in modern Russian.

- ^ "His Majesty is an autocratic monarch, who should not give an answer to anyone in the world in his affairs"

- ^ From 1860 to 1905, the Russian Empire occupied all territories of the present-day Russian Federation, with the exception of the present-day Kaliningrad Oblast, Kuril Islands, and Tuva. In 1905 Russia lost southern Sakhalin to Japan, but in 1914 the Empire established a protectorate over Tuva.

- ^ A ukaz of 1879 gave the governors the right to report secretly on the qualifications of candidates for the office of justice of the peace. In 1889, Alexander III abolished the election of justices of the peace, except in certain large towns and some outlying parts of the Empire, and greatly restricted the right of trial by jury. The combining of judicial and administrative functions was introduced again by the appointment of officials as judges. In 1909, the third Duma restored the election of justices of the peace.