User:Noorullah21/Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khalji

| Bakhtiyar Khalji | |

|---|---|

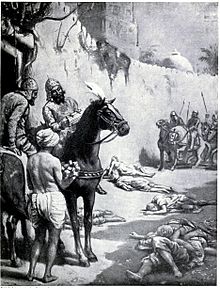

Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji and his fellow warrior Subahdar Awlia Khan leading troops in the slaughter of Buddhist monks at the Nalanda University. Early 20th-century illustration.[1] | |

| Ruler of (Bengal) | |

| Reign | c. 1203 – 1206 |

| Predecessor | Lakshmana Sena (Sena) |

| Successor | Muhammad Shiran Khalji |

| Born | c. 1150 Garmsir, Helmand, Afghanistan |

| Died | c. 1206 Devkot , South Dinajpur, West Bengal |

| Burial | 1206 Pirpal Dargah, Narayanpur, Gangarampur, West Bengal |

| Clan | Khilji |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī (Pashto: اختیارالدین محمد بختیار غلجي 1150 — 1206), or simply known as Bakhtiyar Khalji,[2][3] was a Turko-Afghan military general of the Ghurid ruler Muhammad of Ghor. Bakhtiyar Khalji principally led the Muslim conquests of Bengal and Bihar, establishing himself as governor, and later independent ruler of the region under the Khalji dynasty of Bengal, which ruled the Bengal from 1203 to 1227 CE.

Early life and origin

[edit]Bakhtiyar Khalji was born and raised in Garmsir, Helmand, in present-day southern Afghanistan. His full name was Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī.[4] He was of Turko-Afghan origin.[5] Bakhtiyar was a member of the Khalaj tribe, which was originally of Turkic origin.[4][6] After being settled in south-eastern Afghanistan for over 200 years, it led to the creation of the Pashtun Ghilji tribe. Later in the Khalji Revolution, the Khaljis faced discrimination and were looked down upon by other Turks for Afghan barbarians.[7][8][9][10]

Little is known about Bakhtiyar's early life, however it is known that he was distinguished from his fellow tribesmen because of his bravery and ambition.[4] Seeking service, he came to Ghazni, which was ruled by the Ghurid ruler Muhammad of Ghor. Disturbed by the sight of Bakhtiyar, he was described as ugly, short, and having extremely long arms that would reach as far as his shin.[11][4] Moreover, Bakhtiyar did not have the money to buy himself a horse or armour, which were requirements for military service. Nonetheless, Muhammad of Ghor offered him a small amount of money as stipend, which Bakhtiyar arrogantly refused.[12]

Departing for Northern India, which had been conquered by the Ghurids, Bakhtiyar was rejected at Delhi from joining the army due to his appearance. Eventually, he found service with the governor of Budaun, the possible first employment of Bakhtiyar.[a][12][14]

Bakhtiyar did not come from an unknown background. His uncle, Muhammad bin Mahmud partook in the Second Battle of Tarain in 1192, where he gained the recognition of Ali Nagauri, who later became the governor of Nagaur. Muhammad was entrusted with governorship of Kashmandi following this, and upon his death, the iqta passed onto Bakhtiyar.[15] Little however, is known about Bakhtiyar's tenure in Kashmandi, and he instead traveled to Awadh, where he met the Ghurid commander of Varanasi. Impressed by Bakhtiyar's bravery, he was given governorship of Bhagwat and Bhiuli.[15]

Rise to power

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hutchinson's story of the nations, containing the Egyptians, the Chinese, India, the Babylonian nation, the Hittites, the Assyrians, the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians, the Phrygians, the Lydians, and other nations of Asia Minor. London, Hutchinson. 1906. p. 169.

- ^ Faruqui, Munis D. (2005). "Review of The Bengal Sultanate: Politics, Economy and Coins (AD 1205–1576)". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 36 (1): 246–248. doi:10.2307/20477310. ISSN 0361-0160. JSTOR 20477310.

Hussain argues ... was actually named Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khalji and not the broadly used Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji

- ^ Hussain, Syed Ejaz (2003). The Bengal Sultanate: Politics, Economy and Coins (AD 1205–1576). New Delhi: Manohar. p. 27. ISBN 9788173044823.

- ^ a b c d Khan 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Chandra 2004, p. 226: "Although the Afghans formed a large group in the army of the Delhi Sultanat, only few Afghan nobles had been accorded important positions. That is why Bakhtiyar Khalji who was part - Afghan had to seek his fortune in Bihar and Bengal."

- ^ Chaurasia 2002, p. 28: "The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, had adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court. They were regarded as barbarians. The Turkish nobles had opposed the ascent of Jalal-ud-din to the throne of Delhi."

- ^ Chaurasia 2002, p. 28: "The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, had adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court. They were regarded as barbarians. The Turkish nobles had opposed the ascent of Jalal-ud-din to the throne of Delhi."

- ^ Oberling 2010: "Indeed, it seems very likely that [the Khalaj] formed the core of the Pashto-speaking Ghilji tribe, the name [Ghilji] being derived from Khalaj."

- ^ Srivastava 1966, p. 98: "His ancestors, after having migrated from Turkistan, had lived for over 200 years in the Helmand valley and Lamghan, parts of Afghanistan called Garmasir or the hot region, and had adopted Afghan manners and customs. They were, therefore, wrongly looked upon as Afghans by the Turkish nobles in India as they had intermarried with local Afghans and adopted their customs and manners. They were looked down as non-Turks by Turks."

- ^ Eraly 2015, p. 126: "The prejudice of Turks was however misplaced in this case, for Khaljis were actually ethnic Turks. But they had settled in Afghanistan long before the Turkish rule was established there, and had over the centuries adopted Afghan customs and practices, intermarried with the local people, and were therefore looked down on as non-Turks by pure-bred Turks."

- ^ Balakrishna 2022.

- ^ a b Nizami 1970, p. 171.

- ^ Nizami 1970, p. 171-172.

- ^ Chandra 2004, p. 41.

- ^ a b Nizami 1970, p. 172.

Bibliography

[edit]- Balakrishna, Sandeep (6 May 2022). "A Portrait of Desolation: Bihar and Bengal in the Aftermath of the Barbarian Bakhtiyar Khalji's Jihad". The Dharma Dispatch. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- Eraly, Abraham (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8.

- Khan, Muhammad Mojlum (21 October 2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal: The Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Kube Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84774-062-5.

- Oberling, Pierre (15 December 2010). "ḴALAJ i. TRIBE". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Chandra, Satish (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526).

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic. ISBN 81-269-0123-3.

- Nizami, K. A. (1970). "Foundation of the Delhi Sultanat". In Habib, Mohammad; Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad (eds.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). Vol. 5. People's Publishing House. OCLC 305725.

- Srivastava, Ashirbadi Lal (1966). The History of India, 1000 A.D.-1707 A.D. (Second ed.). Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 98. OCLC 575452554.