User:Nikaiaharris/The National American Woman Suffrage Association

Before the formation of The National American Woman Suffrage Association there was two separate women suffrage associations: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). However, after several negotiations from the two separate associations, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed.

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA)

[edit]

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was one of two rival groups that would eventually combine to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The all-female NWSA, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony was formed on May 15, 1869 due to frustration that women would not be specifically included in the Fifteenth Amendment, which would grant black men the right to vote.[1] The group that opposed the Fifteenth Amendment in favor of women’s suffrage split from the rest of the Women’s Rights Movement (ERA) and followed Stanton and Anthony in search of more. Stanton and Anthony firmly believed that women deserved a federal amendment that would specifically grant and protect women’s suffrage, and on that belief, the NWSA would fight tirelessly to achieve this dream until 1890, when they would join forces with the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).[2] Compared to the AWSA, the NWSA was considered more radical and focused more on women’s rights at the federal level. Although the NWSA’s main focus was Women’s suffrage, the group also pushed other social issues that affected women, like marriage and divorce. The most memorable and distinctive characteristic of the NWSA was their determination to obtain a federal constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage, which would eventually be achieved through the Nineteenth Amendment, which would be ratified in 1920.[3]

The NWSA between 1869 and 1890

[edit]The NWSA conducted various campaigns and actions from the time it was formed until its merge with the AWSA. The most notable push of the NWSA was the encouragement of women to attempt to vote, and if prevented, to file lawsuits in argument that the Fifteenth Amendment indirectly enfranchised women the right to vote.[4] This push would lead to the arrest and conviction of Susan B. Anthony when she attempted to vote, and the ruling by the supreme court that women were not indirectly protected under the Fifteenth Amendment.[5] The NWSA also established the International Council of Women in 1888 in Washington, DC, which is still an active council in today’s society.

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA)

[edit]The second of the rival groups that would eventually become the NAWSA was the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Led by Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe, the AWSA was also organized in November of 1869 in the pursuit of gaining women the right to vote.[6] The AWSA uniquely favored state-by-state campaigns and focused primarily on lobbying state governments to expand women’s voting rights in the United States. The AWSA would gain victory in both Wyoming and Utah, which granted women the right to vote in 1869 and 1870. Lucy Stone, the leader of the AWSA, gave the organization a voice through her weekly newspaper titled the ‘Woman’s Journal’.[7] The AWSA, being the less radical of the two groups, still made a significant contribution to the women’s suffrage movement and would add a variety of both men and women to the combined NAWSA when the groups merged in 1890.

The AWSA between 1869 and 1890

[edit]Before merging with the NWSA, the main campaigns of the AWSA revolved around lobbying states to grant women the right to vote. These pushes were successful in Wyoming and Utah at the beginning of the formation of the AWSA, with Wyoming granting the right to vote in December of 1869, and Utah just two months later at the start of 1870. Additionally, the first publication of the Woman’s journal was on January 8th of 1870, and would continue to be a large part of the AWSA’s campaign. Up until the merge in 1890, the men and women of the AWSA went from state to state fighting for women’s suffrage and continued to push for women’s rights well after the merge and even after women gained the right to vote. The Women’s Journal continued to be a political voice until 1917 when it merged with The Women Citizen. The tactic of using journalism as a voice within a movement is still used today, following in the footsteps of the Women’s Journal. [8]

The NWSA versus The AWSA

[edit]Despite their common focus, the NWSA and AWSA held a few differences that led to their initial split from each other before joining forces and becoming the NAWSA. Their most obvious and known difference was the level of government that they targeted, with the NWSA focusing on the federal level, and the AWSA focusing on the state level. Additionally, the AWSA included American’s of both genders, while the NWSA was an all-female organization.[9] The AWSA focused exclusively on the right to vote, while the NWSA would fight for additional issues related to gender equality within its campaign. Yet, even with their differences, their eventual merge would be a powerful and effective jump in the women’s suffrage movement.

The Merge

[edit]

For over two decades the National Woman Suffrage Association and Woman Suffrage Association existed separately due to different views. Multiple suffragists attempted to merge the two associations to become stronger in the cause, however, they were unsuccessful. [10] When Stone (the leader of the AWSA), fell sick she worked diligently for the merger. She introduced an "umbrella organization" that would include the two separate organizations along with their separate views within the same overall category as a way to eventually merge. [11] That idea did not last however, it began the negotiations that would eventually lead to the desired merge. By January 1889, an agreement was reached. [12] With the recent merge between the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association, the National American Woman Suffrage Association combined techniques from both associations to fight for what would ultimately be known as the 19th amendment through many organized campaigns, protests, and mass meetings.

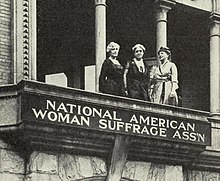

The National American Woman Suffrage Association

[edit]With the recent merge between the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association, the National American Woman Suffrage Association combined techniques from both associations to fight for what would ultimately be known as the 19th amendment through many organized campaigns. [13]

Carrie Chapman Catt

[edit]Carrie Chapman Catt was one of the most vital leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Her role was crucial in campaigns that made a difference to win voting rights for women. [14] Catt was able to capture the attention of not only her peers but her critics and her scholars through her relentless efforts to be an advocate for women who felt they had no voice.[15]

First National Woman Suffrage Pageant

[edit]The National American Woman Suffrage Association was in charge of the First National Woman's Suffrage Pageant. The 1913 pageant demonstrated fragments of what woman's suffrage meant. Thousands of women traveled across the United States despite their age and social class, to march through the capitol city demanding to vote thanks to the pageant.[16] The pageant was said to betray the conflict within the NAWSA between "conciliatory and militant voices". Yet, a writer for the pageant, Helen Mackaye stated, "Women are becoming more and more alive to the fact that the working world is man-made, and that women will have to put up a good fight to get a fair share... through pageantry, we women can set forth our ideals and aspirations more graphically than in any other way".

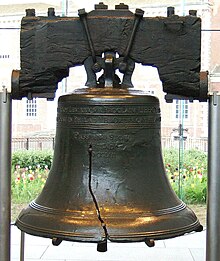

The Liberty Bell

[edit]The Liberty Bell, also known as the Justice Bell, was a crucial element and symbol to the woman's suffrage movement. The bell was created to promote the women's suffrage campaign. The Liberty Bell was also the face of the unsuccessful 1915 campaign for woman suffrage in Pennsylvania. A woman by the name of Katherine Wentworth Ruschenberger purchased the bell and brought it along a statewide tour leading up to the Election Day in 1915. Today, the bell serves as a reminder of the many failed attempts for women's right but ultimately the life-changing victory.

The 19th Amendment

[edit]In 1920, the 19th amendment was finally passed. This marked a tremendous win and the beginning of the end for women's suffrage. Because of countless women's efforts and their unified voices the necessary changes were finally made. The amendment simply granted women the right to vote, but it also accomplished so much more. It gave women confidence, meaning, and power.[17] Although, there was ways to go after the 19th amendment passed, the United States of America would never be the same.

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

[edit]Lead

[edit]Article body

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The National American Woman Suffrage Association | Articles and Essays | National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) | Significance & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) | exhibits.hsp.org". digitalhistory.hsp.org. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ McCammon, Holly J.; Campbell, Karen E.; Granberg, Ellen M.; Mowery, Christine (2001). "How Movements Win: Gendered Opportunity Structures and U.S. Women's Suffrage Movements, 1866 to 1919". American Sociological Review. 66 (1): 49–70. doi:10.2307/2657393. ISSN 0003-1224.

- ^ McCammon, Holly J.; Campbell, Karen E.; Granberg, Ellen M.; Mowery, Christine (2001). "How Movements Win: Gendered Opportunity Structures and U.S. Women's Suffrage Movements, 1866 to 1919". American Sociological Review. 66 (1): 49–70. doi:10.2307/2657393. ISSN 0003-1224.

- ^ Dolton, Patricia F.; Graham, Aimee (2014). "Women's Suffrage Movement". Reference & User Services Quarterly. 54 (2): 31–36. ISSN 1094-9054.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/81/3/787/2234659. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/81/3/787/2234659. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "19th at 100: NWSA and AWSA". 19th at 100: Commemorating the Suffrage Struggle and Its Legacies in Northeast Ohio. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "National American Woman Suffrage Association". History of U.S. Woman's Suffrage. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "Suffrage Movements Merge 1890". www.historycentral.com. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "Suffrage Movements Merge 1890". www.historycentral.com. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "The National American Woman Suffrage Association | Articles and Essays | National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "Carrie Chapman Catt | Articles and Essays | National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ https://content.ebscohost.com/cds/retrieve?content=AQICAHjIloLM_J-oCztr2keYdV8f1ibHmDucods679W_YPnffAHBT0B8R84X9z1ZGiDyZJL7AAAA4zCB4AYJKoZIhvcNAQcGoIHSMIHPAgEAMIHJBgkqhkiG9w0BBwEwHgYJYIZIAWUDBAEuMBEEDA8dw_5sY-E6cvO0rwIBEICBm3MBcnpmlWs45uFzAF3RUJve9nsIyVSwzemUw63bGCAEZmMOhspRSsdywZQW7B-aaqpuvr39Kk_T8SlgrgWpUFQwPz8TJb8O3ROEzMheAmfFhQj10Ul0elfIerXVgpgkHI9VZnGr83SpHflWNLGonQon-ecbmpfreAXciry8j5ZhHOrONYxzbBIBFAs0j3Q1OutpfGBHA4L0K4TY.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://content.ebscohost.com/cds/retrieve?content=AQICAHjIloLM_J-oCztr2keYdV8f1ibHmDucods679W_YPnffAFmSW4iIhJB9DD7IoZn06K_AAAA3zCB3AYJKoZIhvcNAQcGoIHOMIHLAgEAMIHFBgkqhkiG9w0BBwEwHgYJYIZIAWUDBAEuMBEEDNo9OPCSGPGot_bQbQIBEICBl3GDv_O6p8oorSQGjfpJzy12_fJJKgcDQlQbvmk8xmbDt_2LNEcbaCglPx3ZsY6C8jKnunXKJU5IH0RhxJD803LxClkLPWEoVjDZH1l7KpfnN5Xop-eaiqv4ODEdb05XvC3HKfxPXc4dcAsJuG0rPrq_UYZVU4m_g1b7S2mWKbZ_i38hkomc8hKBJdztv3u0eFUWxQ2ppks=.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Women's Right to Vote (1920)". National Archives. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2023-04-11.