User:Newburyjohn/sandbox

To be hanged, drawn and quartered (less commonly "hung, drawn and quartered") was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III (1216–1272) and his successor, Edward I (1272–1307). Convicts were fastened to a hurdle, or wooden panel, and drawn by horse to the place of execution, where they were hanged (almost to the point of death), emasculated, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered (chopped into four pieces). Their remains were often displayed in prominent places across the country, such as London Bridge. For reasons of public decency, women convicted of high treason were instead burnt at the stake.

The severity of the sentence was measured against the seriousness of the crime. As an attack on the monarch's authority, high treason was considered an act deplorable enough to demand the most extreme form of punishment, and although some convicts had their sentences modified and suffered a less ignominious end, over a period of several hundred years many men found guilty of high treason were subjected to the law's ultimate sanction. This included many English Catholic priests executed during the Elizabethan era, and several of the regicides involved in the 1649 execution of King Charles I.

Although the Act of Parliament that defines high treason remains on the United Kingdom's statute books, during a long period of 19th-century legal reform the sentence of hanging, drawing and quartering was changed to drawing, hanging until dead, and posthumous beheading and quartering, before being rendered obsolete in England in 1870. The death penalty for treason was abolished in 1998.

Etymology

[edit]The use of the word drawn, as in "to draw", has caused a degree of confusion. One of the Oxford English Dictionary's definitions of draw is "to draw out the viscera or intestines of; to disembowel (a fowl, etc. before cooking, a traitor or other criminal after hanging)", but this is followed by "in many cases of executions it is uncertain whether this, or sense 4 [To drag (a criminal) at a horse's tail, or on a hurdle or the like, to the place of execution; formerly a legal punishment of high treason], is meant. The presumption is that where drawn is mentioned after hanged, the sense is as here."[1] Historian Ram Sharan Sharma arrives at the same conclusion: "Where, as in the popular hung, drawn and quartered (meaning, facetiously, of a person, completely disposed of), drawn follows hanged or hung, it is to be referred to as the disembowelling of the traitor."[2] The historian and author Ian Mortimer disagrees. In an essay published on his website, he writes that the separate mention of evisceration is a relatively modern device, and that while it certainly took place on many occasions, the presumption that drawing means to disembowel is spurious. Instead, drawing (as a method of transportation) may be mentioned after hanging because it was a supplementary part of the execution.[3]

Treason in England

[edit]

During the High Middle Ages those in England guilty of treason were punished in a variety of ways, including drawing and hanging. In the 13th century other, more brutal penalties were introduced, such as disembowelling, burning, beheading and quartering. The 13th-century English chronicler Matthew Paris described how in 1238 "a certain man at arms, a man of some education (armiger literatus)"[4] attempted to kill Henry III. His account records in gruesome detail how the would-be assassin was executed: "dragged asunder, then beheaded, and his body divided into three parts; each part was then dragged through one of the principal cities of England, and was afterwards hung on a gibbet used for robbers."[5][nb 1] He was apparently sent by William de Marisco, an outlaw who some years earlier had killed a man under royal protection before fleeing to Lundy Island. De Marisco was captured in 1242 and on Henry's order dragged from Westminster to the Tower of London to be executed. There he was hanged from a gibbet until dead. His corpse was disembowelled, his entrails burnt, his body quartered and the parts distributed to cities across the country.[7] The punishment is more frequently recorded during Edward I's reign.[8] Welshman Dafydd ap Gruffydd became the first nobleman in England to be hanged, drawn and quartered after he turned against the king and proclaimed himself Prince of Wales and Lord of Snowdon.[9] Dafydd's rebellion infuriated Edward so much that he demanded a novel punishment. Therefore, following his capture and trial in 1283, for his betrayal he was drawn by horse to his place of execution. For killing English nobles he was hanged alive. For killing those nobles at Easter he was eviscerated and his entrails burnt. For conspiring to kill the king in various parts of the realm, his body was quartered and the parts sent across the country; his head was placed on top of the Tower of London.[10] A similar fate was suffered by the Scottish rebel leader Sir William Wallace. Captured and tried in 1305, he was forced to wear a crown of laurel leaves and was drawn to Smithfield, where he was hanged and beheaded. His entrails were then burnt and his corpse quartered. His head was set on London Bridge and the quarters sent to Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling and Perth.[11]

These and other executions, such as those of Andrew Harclay, 1st Earl of Carlisle[12] and Hugh Despenser the Younger,[13] which each occurred during Edward II's reign, happened when acts of treason in England, and their punishments, were not clearly defined in common law.[nb 2] Treason was based on an allegiance to the sovereign from all subjects aged 14 or over and it remained for the king and his judges to determine if that allegiance had been broken.[15] Edward III's justices had offered somewhat over-zealous interpretations of what activities constituted treason, "calling felonies treasons and afforcing indictments by talk of accroachment of the royal power",[16] prompting parliamentary demands to clarify the law. Edward therefore introduced the Treason Act 1351. It was enacted at a time in English history when a monarch's right to rule was indisputable and was therefore written principally to protect the throne and sovereign.[17] The new law offered a narrower definition of treason than had existed before and split the old feudal offence into two classes.[18][19] Petty treason referred to the killing of a master (or lord) by his servant, a husband by his wife, or a prelate by his clergyman. Men guilty of petty treason were drawn and hanged, whereas women were burnt.[nb 3][22]

High treason was the most egregious offence an individual could commit. Attempts to undermine the king's authority were viewed with as much seriousness as if the accused had attacked him personally, which itself would be an assault on his status as sovereign and a direct threat to his right to govern. As this might undermine the state, retribution was considered an absolute necessity and the crime deserving of the ultimate punishment.[23] The practical difference between the two offences therefore was in the consequence of being convicted; rather than being drawn and hanged, men were to be hanged, drawn and quartered, while for reasons of public decency (their anatomy being considered inappropriate for the sentence), women were instead drawn and burnt.[21][24] The Act declared that a person had committed high treason if they were: compassing or imagining the death of the king, his wife or his eldest son and heir; violating the king's wife, his eldest daughter if she was unmarried, or the wife of his eldest son and heir; levying war against the king in his realm; adhering to the king's enemies in his realm, giving them aid and comfort in his realm or elsewhere; counterfeiting the Great Seal or the Privy Seal, or the king's coinage; knowingly importing counterfeit money; killing the Chancellor, Treasurer or one of the king's Justices while performing their offices.[16] However, the Act did not limit the king's authority in defining the scope of treason. It contained a proviso giving English judges discretion to extend that scope whenever required, a process more commonly known as constructive treason.[25][nb 4] It also applied to subjects overseas in British colonies in the Americas and although some executions for treason were performed in the provinces of Maryland and Virginia, only two colonists were hanged, drawn and quartered; in 1630, William Matthews in Virginia, and in the 1670s, Joshua Tefft in New England. Later sentences resulted either in a pardon or a hanging.[27]

Only one witness was required to convict a person of treason, although in 1552 this was increased to two. Suspects were first questioned in private by the Privy Council before they were publicly tried. They were allowed no witnesses or defence counsel, and were generally presumed guilty from the outset. This meant that for centuries anyone accused of treason found themselves severely legally disadvantaged, a situation which lasted until the late 17th century, when several years of politically motivated treason charges made against Whig politicians prompted the introduction of the Treason Act of 1695.[28] This allowed defendants counsel, witnesses, a copy of their indictment and a jury, and when not charged with an attempt on the monarch's life, they were to be prosecuted within three years of the alleged offence.[29]

Execution of the sentence

[edit]Once sentenced, malefactors were usually held in prison for a few days before being taken to the place of execution. During the early Middle Ages this journey may have been made tied directly to the back of a horse, but it subsequently became customary to be fastened instead to a wicker hurdle, or wooden panel, itself tied to the horse.[30] Historian Frederic William Maitland thought that this was probably to "[secure] for the hangman a yet living body".[31]

Although some reports indicate that during Mary I's reign bystanders were vocal in their support, while in transit convicts sometimes suffered directly at the hands of the crowd. William Wallace was whipped, attacked and had rotten food and waste thrown at him,[32] and the priest Thomas Prichard was reportedly barely alive by the time he reached the gallows in 1587. Others found themselves admonished by "zealous and godly men";[30] it became customary for a preacher to follow the condemned, asking them to repent. According to Samuel Clarke, the Puritan clergyman William Perkins (1558–1602) once managed to convince a young man at the gallows that he had been forgiven, enabling the youth to go to his death "with tears of joy in his eyes ... as if he actually saw himself delivered from the hell which he feared before, and heaven opened for receiving his soul".[33]

After the king's commission had been read aloud, the crowd were normally asked to move back from the scaffold before being addressed by the convict.[34] While these speeches were mostly an admission of guilt (although few admitted treason),[35] still they were carefully monitored by the sheriff and chaplain, who were occasionally forced to act; in 1588 the Catholic priest William Dean's address to the crowd was considered so inappropriate that he was gagged almost to the point of suffocation.[34][36] Questions on matters of allegiance and politics were sometimes put to the prisoner,[37] as happened to Edmund Gennings in 1591. He was asked by Priest-hunter Richard Topcliffe to "confess his treason", but when Gennings responded "if to say Mass be treason, I confess to have done it and glory in it", Topcliffe ordered him to be quiet and instructed the hangman to push him off the ladder.[38] Sometimes the witness responsible for the condemned man's execution was also present. A government spy, John Munday, was in 1582 present for the execution of Thomas Ford. Munday supported the sheriff, who had reminded the priest of his confession when he protested his innocence.[39] The sentiments expressed in such speeches may be related to the conditions encountered during imprisonment. Many Jesuit priests suffered badly at the hands of their captors but were frequently the most defiant; conversely, those of a higher station were often the most apologetic. Such contrition may have arisen from the sheer terror felt by those who thought they might be disembowelled rather than simply beheaded as they would normally expect, and any apparent acceptance of their fate may have stemmed from the belief that a serious, but not treasonable act, had been committed. Good behaviour at the gallows may also have been due to a convict's desire for his heirs not to be disinherited.[40]

The condemned were occasionally forced to watch as other traitors, sometimes their confederates, were executed before them. The priest James Bell was in 1584 made to watch as his companion, John Finch, was "a-quarter-inge". Edward James and Francis Edwardes were made to witness Ralph Crockett's execution in 1588, in an effort to elicit their cooperation and acceptance of Queen Elizabeth's religious supremacy before they were themselves executed.[41] Normally stripped to the shirt with their arms bound in front of them, prisoners were then hanged for a short period, either from a ladder or cart. On the sheriff's orders the cart would be taken away (or if a ladder, turned), leaving the man suspended in mid-air. The aim was usually to cause strangulation and near-death, although some victims were killed prematurely, the priest John Payne's death in 1582 being hastened by a group of men pulling on his legs. Conversely, some, such as the deeply unpopular William Hacket (d. 1591), were cut down instantly and taken to be disembowelled and normally emasculated—the latter, according to Sir Edward Coke, to "show his issue was disinherited with corruption of blood."[nb 5].[42]

Those still conscious at that point might have seen their entrails burnt, before their heart was removed and the body decapitated and quartered (chopped into four pieces). The regicide Major-General Thomas Harrison, after being hanged for several minutes and then cut open in October 1660, was reported to have leaned across and hit his executioner—resulting in the swift removal of his head. His entrails were thrown onto a nearby fire.[43][44][nb 6] John Houghton was reported to have prayed while being disembowelled in 1535, and in his final moments to have cried "Good Jesu, what will you do with my heart?"[47][48] Executioners were often inexperienced and proceedings did not always run smoothly. In 1584 Richard White's executioner removed his bowels piece by piece, through a small hole in his belly, "the which device taking no good success, he mangled his breast with a butcher's axe to the very chine most pitifully".[49][nb 7] At his execution in January 1606 for his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot, Guy Fawkes managed to break his neck by jumping from the gallows, cheating the executioner.[53][54]

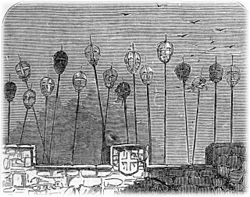

No records exist to demonstrate exactly how the corpse was quartered, although the image on the right, of the quartering of Sir Thomas Armstrong in 1684, shows the executioner making vertical cuts through the spine and removing the legs at the hip.[55] The distribution of Dafydd ap Gruffydd's remains was described by Herbert Maxwell: "the right arm with a ring on the finger in York; the left arm in Bristol; the right leg and hip at Northampton; the left [leg] at Hereford. But the villain's head was bound with iron, lest it should fall to pieces from putrefaction, and set conspicuously upon a long spear-shaft for the mockery of London."[56] After the execution in 1660 of several of the regicides involved in the death of Charles I eleven years earlier, the diarist John Evelyn remarked: "I saw not their execution, but met their quarters, mangled, and cut, and reeking, as they were brought from the gallows in baskets on the hurdle."[57] Such remains were typically parboiled and displayed as a gruesome reminder of the penalty for high treason, usually wherever the traitor had conspired or found support.[44][58] The head was often displayed on London Bridge, for centuries the route by which many travellers from the south entered the city. Several eminent commentators remarked on the displays. In 1566 Joseph Justus Scaliger wrote that "in London there were many heads on the bridge ... I have seen there, as if they were masts of ships, and at the top of them, quarters of men's corpses". In 1602 the Duke of Stettin emphasised the ominous nature of their presence when he wrote "near the end of the bridge, on the suburb side, were stuck up the heads of thirty gentlemen of high standing who had been beheaded on account of treason and secret practices against the Queen".[59][nb 8] The practice of using London Bridge in this manner ended following the hanging, drawing and quartering in 1678 of William Staley, a victim of the fictitious Popish Plot. His quarters were given to his relatives, who promptly arranged a "grand" funeral; this incensed the coroner so much that he ordered the body to be dug up and set upon the city gates. Staley's was the last head to be placed on London Bridge.[61][62]

Later history

[edit]Another victim of the Popish Plot, Oliver Plunket the Archbishop of Armagh, was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn in July 1681. His executioner was bribed so that Plunket's body parts were saved from the fire; the head is now displayed at St Peter's Church in Drogheda.[63] Plunket was the last Catholic priest in England to be martyred but not the last person in England to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Francis Towneley and several other captured Jacobite officers involved in the Jacobite Rising of 1745 were executed,[64] but by then the executioner possessed some discretion as to how much they should suffer and thus they were killed before their bodies were eviscerated. The French spy François Henri de la Motte was hanged in 1781 for almost an hour before his heart was cut out and burnt,[65] and the following year David Tyrie was hanged, decapitated and then quartered at Portsmouth. Pieces of his corpse were fought over by members of the 20,000-strong crowd there, some making trophies of his limbs and fingers.[66] In 1803 Edward Despard and six co-conspirators in the Despard Plot were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Before they were hanged and beheaded at Horsemonger Lane Gaol, they were first placed on sledges attached to horses, and ritually pulled in circuits around the gaol yards.[67] Their execution was attended by an audience of about 20,000.[68] A contemporary report describes the scene after Despard had made his speech:

This energetic, but inflammatory appeal, was followed by such enthusiastic plaudits, that the Sheriff hinted to the Clergyman to withdraw, and forbade Colonel Despard to proceed. The cap was then drawn over their eyes, during which the Colonel was observed again to fix the knot under his left ear, and, at seven minutes before nine o'clock the signal being given, the platform dropped, and they were all launched into eternity. From the precaution taken by the Colonel, he appeared to suffer very little, neither did the others struggle much, except Broughton, who had been the most indecently profane of the whole. Wood, the soldier, died very hard. The Executioners went under, and kept pulling them by the feet. Several drops of blood fell from the fingers of Macnamara and Wood, during the time they were suspended. After hanging thirty-seven minutes, the Colonel's body was cut down, at half an hour past nine o'clock, and being stripped of his coat and waistcoat, it was laid upon saw-dust, with the head reclined upon a block. A surgeon then in attempting to sever the head from the body by a common dissecting knife, missed the particular joint aimed at, when he kept haggling it, till the executioner was obliged to take the head between his hands, and to twist it several times round, when it was with difficulty severed from the body. It was then held up by the executioner, who exclaimed—"Behold the head of EDWARD MARCUS DESPARD, a Traitor!" The same ceremony followed with the others respectively; and the whole concluded by ten o'clock.[69]

At the burnings of Isabella Condon in 1779 and Phoebe Harris in 1786, the sheriffs present inflated their expenses; in the opinion of Dr Simon Devereaux they were probably dismayed at being forced to attend such spectacles.[70] Harris's fate prompted William Wilberforce to sponsor a bill which if passed would have abolished the practice, but as one of its proposals would have allowed the anatomical dissection of criminals other than murderers, the House of Lords rejected it.[71] The burning in 1789 of Catherine Murphy, a counterfeiter,[nb 9] prompted Sir Benjamin Hammett to impugn her sentence in Parliament. He called it one of "the savage remains of Norman policy"[65][72] and subsequently, amidst a growing tide of public disgust at the burning of women, Parliament passed the Treason Act 1790, which for women guilty of treason substituted hanging for burning.[73] It was followed by the Treason Act 1814, introduced by Samuel Romilly, a legal reformer. Influenced by his friend, Jeremy Bentham, Romilly had long argued that punitive laws should serve to reform criminal behaviour and that far from acting as a deterrent, the severity of England's laws was responsible for an increase in crime. When appointed the MP for Queensborough in 1806 he resolved to improve what he described as "Our sanguinary and barbarous penal code, written in blood".[74] He managed to repeal the death penalty for certain thefts and vagrancy, and in 1814 proposed to change the sentence for men guilty of treason to being hanged until dead and the body left at the king's disposal. However, when it was pointed out that this would be a less severe punishment than that given for murder, he agreed that the corpse should also be decollated, "as a fit punishment and appropriate stigma."[75][76] This is what happened to Jeremiah Brandreth, leader of a 100-strong contingent of men in the Pentrich Rising and one of three men executed in 1817 at Derby Gaol. As with Edward Despard and his confederates the three were drawn to the scaffold on sledges before being hanged for about an hour, and then on the insistence of the Prince Regent were beheaded with an axe. The local miner appointed to the task of beheading them was inexperienced though, and having failed with the first two blows, completed his job with a knife. As he held the first head up and made the customary announcement, the crowd reacted with horror and fled. A different reaction was seen in 1820, when amidst more social unrest five men involved in the Cato Street Conspiracy were hanged and beheaded at Newgate Prison. Although the beheading was performed by a surgeon, following the usual proclamation the crowd was angry enough to force the executioners to find safety behind the prison walls.[77] The plot was the last real crime for which the sentence was applied.[78]

Reformation of England's capital punishment laws continued throughout the 19th century, as politicians such as John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, sought to remove from the statute books many of the capital offences that remained.[79] Robert Peel's drive to ameliorate law enforcement saw petty treason abolished by the Offences against the Person Act 1828, which removed the distinction between crimes formerly considered as petty treason, and murder.[80][81] The Royal Commission on Capital Punishment 1864-1866 recommended that there be no change to treason law, quoting the "more merciful" Treason Felony Act 1848, which limited the punishment for most treasonous acts to penal servitude. Its report recommended that for "rebellion, assassination or other violence ...we are of opinion that the extreme penalty must remain",[82] although the most recent occasion (and ultimately, the last) on which anyone had been sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered was in November 1839, following the Chartist Newport Rising—and those men sentenced to death were instead transported.[83] The report highlighted the changing public mood toward public executions (brought about in part by the growing prosperity created by the Industrial Revolution). Home Secretary Spencer Horatio Walpole told the commission that executions had "become so demoralizing that, instead of its having a good effect, it has a tendency rather to brutalize the public mind than to deter the criminal class from committing crime". The commission recommended that executions should be performed privately, behind prison walls and away from the public's view, "under such regulations as may be considered necessary to prevent abuse, and to satisfy the public that the law has been complied with."[84] The practice of executing criminals in public was ended two years later by the Capital Punishment Amendment Act 1868, introduced by Home Secretary Gathorne Hardy. An amendment to abolish capital punishment completely, suggested before the bill's third reading, failed by 127 votes to 23.[85][86]

Hanging, drawing and quartering was rendered obsolete in England by the Forfeiture Act 1870, Liberal politician Charles Forster's second attempt since 1864[nb 10] to end the forfeiture of a felon's lands and goods (thereby not making paupers of his family).[88][89] The Act also limited the penalty for treason to hanging alone,[90] although it did not remove the monarch's right under the 1814 Act to replace hanging with beheading.[76][91] The death penalty for treason was abolished by the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, enabling the UK to ratify protocol six of the European Convention on Human Rights in 1999.[92]

References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ "Rex eum, quasi regiae majestatis (occisorem), membratim laniatum equis apud Coventre, exemplum terribile et spectaculum comentabile praebere (iussit) omnibus audentibus talia machinari. Primo enim distractus, postea decollatus et corpus in tres partes divisum est."[6]

- ^ Treason before 1351 was defined by Alfred the Great's Doom book. As Patrick Wormald wrote, "if anyone plots against the king's life ... [or his lord's life], he is liable for his life and all that he owns ... or to clear himself by the king's [lord's] wergeld."[14]

- ^ Women were considered the legal property of their husbands,[20] and so a woman convicted of killing her husband was guilty not of murder, but petty treason. For disrupting the social order a degree of retribution was therefore required; hanging was considered insufficient for such a heinous crime.[21]

- ^ "And because that many other like cases of treason may happen in time to come, which a man cannot think nor declare at this present time; it is accorded, that if any other case supposed treason, which is not above specified, doth happen before any justice, the justice shall tarry without going to judgement of treason, till the cause be shewed and declared before the king and his parliament, whether it ought to be judged treason or other felony." Edward Coke[26]

- ^ For an explanation of "corruption of blood", see Attainder.

- ^ Harrison's sentence was 'That you be led to the place from whence you came, and from thence be drawn upon a hurdle to the place of execution, and then you shall be hanged by the neck and, being alive, shall be cut down, and your privy members to be cut off, and your entrails be taken out of your body and, you living, the same to be burnt before your eyes, and your head to be cut off, your body to be divided into four quarters, and head and quarters to be disposed of at the pleasure of the King's majesty. And the Lord have mercy on your soul.'[45] His head adorned the sledge which drew fellow regicide John Cooke to his execution, before later being displayed in Westminster Hall; his quarters were fastened to the city gates.[46]

- ^ In the case of Hugh Despenser the Younger, Seymour Phillips writes: "All the good people of the realm, great and small, rich and poor, regarded Despenser as a traitor and a robber; for which he was sentenced to be hanged. As a traitor he was to be drawn and quartered and the quarters distributed around the kingdom; as an outlaw he was to be beheaded; and for procuring discord between the king and the queen and other people of the kingdom he was sentenced to be disembowelled and his entrails burned; finally he was declared to be a traitor, tyrant and renegade."[50] In Professor Robert Kastenbaum's opinion the disfigurement of Despenser's corpse (presuming that his disembowelment was post-mortem) may have served as a reminder to the crowd that the authorities did not tolerate dissent. He speculates that the reasoning behind such bloody displays may have been to assuage the crowd's anger, to remove any human characteristics from the corpse, to rob the criminal's family of any opportunity to hold a meaningful funeral, or even to release any evil spirits contained within.[51] The practice of disembowelling the body may have originated in the medieval belief that treasonable thoughts were housed there, requiring that the convict's entrails be "purged by fire".[49] Andrew Harclay's "treasonous thoughts had originated in his 'heart, bowels and entrails'", and so were to be "extracted and burnt to ashes, which would then be dispersed", as had happened with William Wallace and Gilbert de Middleton.[52]

- ^ Women's heads sometimes adorned the bridge, such as that of Elizabeth Barton, a domestic servant and later nun who forecast the early death of Henry VIII. She was drawn to Tyburn in 1534, and hanged and beheaded.[60]

- ^ Although women were usually burnt only after they had first been strangled to death, in 1726 Catherine Hayes's executioner botched the job and she perished in the flames, the last woman in England to do so.[65]

- ^ Forster's first attempt passed through both Houses of Parliament without obstruction, but was dropped following a change of government.[87]

Notes

- ^ "draw", Oxford English Dictionary ((subscription or participating institution membership required)) (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, hosted at dictionary.oed.com, 1989, retrieved 18 August 2010.

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format= - ^ Sharma 2003, p. 9

- ^ Mortimer, Ian (30 March 2010), Why do we say ‘hanged, drawn and quartered?’ (PDF), ianmortimer.com, retrieved 20 August 2010

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Powicke 1949, pp. 54–58

- ^ Giles 1852, p. 139

- ^ Bellamy 2004, p. 23

- ^ Lewis & Paris 1987, p. 234

- ^ Diehl & Donnelly 2009, p. 58

- ^ Beadle & Harrison 2008, p. 11

- ^ Bellamy 2004, pp. 23–26

- ^ Murison 2003, pp. 147–149

- ^ Summerson, Henry (2008) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12235 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12235, retrieved 18 August 2010

{{citation}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Hamilton, J. S. (2008) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7554 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7554, retrieved 19 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Wormald 2001, pp. 280–281

- ^ Tanner 1940, p. 375

- ^ a b Bellamy 1979, p. 9

- ^ Tanner 1940, pp. 375–376

- ^ Bellamy 1979, pp. 9–10

- ^ Dubber 2005, p. 25

- ^ Caine & Sluga 2002, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b Briggs 1996, p. 84

- ^ Blackstone et al. 1832, pp. 156–157

- ^ Foucault 1995, pp. 47–49

- ^ Naish 1991, p. 9

- ^ Bellamy 1979, pp. 10–11

- ^ Coke, Littleton & Hargrave 1817, pp. 20–21

- ^ Ward 2009, p. 56

- ^ Tomkovicz 2002, p. 6

- ^ Feilden 2009, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b Bellamy 1979, p. 187

- ^ Pollock & Maitland 2007, p. 500

- ^ Beadle & Harrison 2008, p. 12

- ^ Clarke 1654, p. 853

- ^ a b Bellamy 1979, p. 191

- ^ Bellamy 1979, p. 195

- ^ Pollen 1908, p. 327

- ^ Bellamy 1979, p. 193

- ^ Pollen 1908, p. 207

- ^ Bellamy 1979, p. 194

- ^ Bellamy 1979, p. 199

- ^ Bellamy 1979, p. 201

- ^ Bellamy 1979, pp. 202–204

- ^ Nenner, Howard (September 2004), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70599 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/70599, retrieved 16 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ a b Abbott 2005, pp. 158–159

- ^ Abbott 2005, p. 158

- ^ Gentles, Ian J. (2008) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12448 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12448, retrieved 19 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Abbott 2005, p. 161

- ^ Hogg, James (2008) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13867 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13867, retrieved 18 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ a b Bellamy 1979, p. 204

- ^ Phillips 2010, p. 517

- ^ Kastenbaum 2004, pp. 193–194

- ^ Westerhof 2008, p. 127

- ^ Northcote Parkinson 1976, pp. 91–92"

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 283

- ^ Lewis 2008, pp. 113–124.

- ^ Maxwell 1913, p. 35

- ^ Evelyn 1850, p. 341

- ^ Bellamy 1979, pp. 207–208

- ^ Abbott 2005, pp. 159–160

- ^ Abbott 2005, pp. 160–161

- ^ Beadle & Harrison 2008, p. 22

- ^ Seccombe, Thomas; Carr, Sarah (2004), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26224 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26224, retrieved 17 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Hanly, John (2006) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22412 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22412, retrieved 17 Aug 2010

{{citation}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Roberts 2002, p. 132

- ^ a b c Gatrell 1996, pp. 316–317

- ^ Poole 2000, p. 76

- ^ Gatrell 1996, pp. 317–318

- ^ Chase, Malcolm (2009) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7548 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7548, retrieved 19 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Granger & Caulfield 1804, pp. 889–897

- ^ Devereaux, pp. 73–93

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 30

- ^ Shelton 2009, p. 88

- ^ Feilden 2009, p. 5

- ^ Block & Hostettler 1997, p. 42

- ^ Romilly 1820, p. xlvi

- ^ a b Joyce 1955, p. 105

- ^ Belchem, John (2008) [2004], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3270 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/3270, retrieved 19 August 2010

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|format=|title=(help) - ^ Abbott 2005, pp. 161–162

- ^ Block & Hostettler 1997, pp. 51–58

- ^ Wiener 2004, p. 23

- ^ Dubber 2005, p. 27

- ^ Levi 1866, pp. 134–135

- ^ Chase 2007, pp. 137–140

- ^ McConville 1995, p. 409

- ^ Gatrell 1996, p. 593

- ^ Block & Hostettler 1997, pp. 59, 72

- ^ Second Reading, HC Deb 30 March 1870 vol 200 cc931-8, hansard.millbanksystems.com, 30 March 1870, retrieved 10 March 2011

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Anon 3 1870, p. N/A

- ^ Anon 2 1870, p. 547

- ^ Forfeiture Act 1870, legislation.gov.uk, 1870, retrieved 10 March 2011

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Anon 1870, p. 221

- ^ Windlesham 2001, p. 81n

Bibliography

- Anon (1870), The Law Times, vol. 49, London: Office of the Law Times

- Anon 2 (1870), The Solicitors' journal & reporter, London: Law Newspaper

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Anon 3 (1870), Public Bills, vol. 2, Great Britain Parliament

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Abbott, Geoffrey (2005) [1994], Execution, a Guide to the Ultimate Penalty, Chichester, West Sussex: Summersdale Publishers, ISBN 1-84024-433-X

- Beadle, Jeremy; Harrison, Ian (2008), Firsts, Lasts & Onlys: Crime, London: Anova Books, ISBN 1-905798-04-0

- Bellamy, John (1979), The Tudor Law of Treason, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7100-8729-2

- Bellamy, John (2004), The Law of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages (Reprinted ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-52638-8

- Blackstone, William; Christian, Edward; Chitty, Joseph; Hovenden, John Eykyn; Ryland, Archer (1832), Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 2 (18th London ed.), New York: Collins and Hannay

- Block, Brian P.; Hostettler, John (1997), Hanging in the balance: a history of the abolition of capital punishment in Britain, Winchester: Waterside Press, ISBN 1-872870-47-3

- Briggs, John (1996), Crime and Punishment in England: an Introductory History, London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-312-16331-2

- Caine, Barbara; Sluga, Glenda (2002), Gendering European History: 1780–1920, London: Continuum, ISBN 0-8264-6775-X

- Chase, Malcolm (2007), Chartism: A New History, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-6087-7

- Clarke, Samuel (1654), The marrow of ecclesiastical history, Unicorn in Pauls-Church-yard: William Roybould

- Coke, Edward; Littleton, Thomas; Hargrave, Francis (1817), The ... part of the institutes of the laws of England; or, a commentary upon Littleton, London: Clarke

- Devereaux, Simon (2006), "The Abolition of the Burning of Women", Crime, Histoire et Sociétés, 2005/2, vol. 9, International Association for the History of Crime and Criminal Justice, ISBN 2-600-01054-8

- Diehl, Daniel; Donnelly, Mark P. (2009), The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-4583-7

- Dubber, Markus Dirk (2005), The police power: patriarchy and the foundations of American government, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-13207-7

- Evelyn, John (1850), William Bray (ed.), Diary and correspondence of John Evelyn, London: Henry Colburn

- Feilden, Henry St. Clair (2009) [1910], A Short Constitutional History of England, Read Books, ISBN 978-1-4446-9107-8

- Fraser, Antonia (2005) [1996], The Gunpowder Plot, Phoenix, ISBN 0-7538-1401-3

- Foucault, Michel (1995), Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Second ed.), New York: Vintage, ISBN 0-679-75255-2

- Gatrell, V. A. C. (1996), The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770–1868, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-285332-5

- Giles, J. A. (1852), Matthew Paris's English history: From the year 1235 to 1273, London: H. G. Bohn

- Granger, William; Caulfield, James (1804), The new wonderful museum, and extraordinary magazine, Paternoster-Row, London: Alex Hogg & Co

- Joyce, James Avery (1955) [1952], Justice at Work: The Human Side of the Law, London: Pan Books

- Kastenbaum, Robert (2004), "On our way: the final passage through life and death", Life Passages, vol. 3, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21880-9

- Lewis, Mary E (2008) [2006], "A Traitor's Death? The identity of a drawn, hanged and quartered man from Hulton Abbey, Staffordshire" (PDF), Antiquity, reading.academia.edu, pp. 113–124

- Lewis, Suzanne; Paris, Matthew (1987), The art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica majora, California: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04981-0

- Levi, Leone (1866), Annals of British Legislation, London: Smith, Elder & Co

- Maxwell, Sir Herbert (1913), The Chronicle of Lanercost, 1272–1346, Glasgow: J Maclehose

- McConville, Seán (1995), English local prisons, 1860–1900: next only to death, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-03295-4

- Murison, Alexander Falconer (2003), William Wallace: Guardian of Scotland, New York: Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-43182-7

- Naish, Camille (1991), Death comes to the maiden: sex and execution, 1431–1933, London: Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-05585-7

- Northcote Parkinson, C. (1976), Gunpowder Treason and Plot, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-77224-4

- Phillips, Seymour (2010), Edward II, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-15657-7

- Poole, Steve (2000), The politics of regicide in England, 1760–1850: Troublesome subjects, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-5035-9

- Pollen, John Hungerford (1908), Unpublished documents relating to the English martyrs, London: J. Whitehead

- Pollock, Frederick (2007), The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (Second ed.), New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange, ISBN 1-58477-718-4

{{citation}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - Powicke, F. M. (1949), Ways of Medieval Life and Thought, New York: Biblo & Tannen Publishers, ISBN 0-8196-0137-3

- Roberts, John Leonard (2002), The Jacobite wars: Scotland and the military campaigns of 1715 and 1745, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 1-902930-29-0

- Romilly, Samuel (1820), The Speeches of Sir Samuel Romilly in the House of Commons: in two volumes, London: Ridgway

- Sharma, Ram Sharan (2003), Encyclopaedia of Jurisprudence, New Delhi: Anmol Publications PVT., ISBN 81-261-1474-6

- Shelton, Don (2009), The Real Mr Frankenstein (e-book), Portmin Press

- Smith, Greg T. (1996), "The Decline of Public Physical Punishment in London", in Carolyn Strange (ed.), Qualities of mercy: Justice, Punishment, and Discretion, Vancouver: UBC Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0585-8

- Tanner, Joseph Robson (1940), Tudor constitutional documents, A.D. 1485–1603: with an historical commentary (second ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Archive

- Tomkovicz, James J. (2002), The right to the assistance of counsel: a reference guide to the United States Constitution, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-31448-9

- Ward, Harry M. (2009), Going down hill: legacies of the American Revolutionary War, Palo Alto, CA: Academica Press, ISBN 978-1-933146-57-7

- Westerhof, Danielle (2008), Death and the noble body in medieval England, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84383-416-8

- Wiener, Martin J. (2004), Men of blood: violence, manliness and criminal justice in Victorian England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-83198-9

- Windlesham, Baron David James George Hennessy (2001), "Dispensing justice", Responses to Crime, vol. 4, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-829844-7

- Wormald, Patrick (2001) [1999], The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century , Legislation and Its Limits, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-22740-7

Template:Featured article is only for Wikipedia:Featured articles.