User:Mr swordfish/List of common misconceptions/History

Appearance

Ancient

[edit]- The Pyramids of Egypt were not constructed with slave labor. Archaeological evidence shows that the laborers were a combination of skilled workers and poor farmers working in the off-season with the participants paid in high-quality food and tax exemptions.[1][2] The idea that slaves were used originated with Herodotus, and the idea that they were Israelites arose centuries after the pyramids were constructed.[3][2]

- Galleys in ancient times were not commonly operated by chained slaves or prisoners, as depicted in films such as Ben Hur, but by paid laborers or soldiers, with slaves used only in times of crisis, in some cases even gaining freedom after the crisis was averted. Ptolemaic Egypt was a possible exception.[4][5] Other types of vessels, such as Roman merchant vessels, were manned by slaves, sometimes even with slaves as ship's master.[6]

- Tutankhamun's tomb is not inscribed with a curse on those who disturb it. This was a media invention of 20th-century tabloid journalists.[7]

- The Minoan civilization was not destroyed by the eruption of Thera and was not the inspiration for Plato's parable of Atlantis.[8]

The ancient Romans did not use the Roman salute depicted in The Oath of the Horatii (1784). - The ancient Greeks did not use the word "idiot" (Ancient Greek: ἰδιώτης, romanized: idiṓtēs) to disparage people who did not take part in civic life. An ἰδιώτης was simply a private citizen as opposed to a government official. The word also meant any sort of non-expert or layman,[9] then later someone uneducated or ignorant, and much later to mean stupid or mentally deficient.[10]

- The Roman salute, in which the arm is fully extended forwards or diagonally with palm down and fingers touching, was not used in ancient Rome. The gesture was first associated with ancient Rome in the 1784 painting The Oath of the Horatii by the French artist Jacques-Louis David, which inspired later salutes, most notably the Nazi salute.[11]

- Wealthy Ancient Romans did not use rooms called vomitoria to purge food during meals so they could continue eating[12] and vomiting was not a regular part of Roman dining customs.[13] A vomitorium of an amphitheatre or stadium was a passageway allowing quick exit at the end of an event.[12]

- Scipio Aemilianus did not sow salt over the city of Carthage after defeating it in the Third Punic War.[14]

- Julius Caesar was not born via caesarean section. Such a procedure would have been fatal to the mother at the time, and Caesar's mother was still alive when he was 45 years old.[15][16]

Middle Ages

[edit]- The Middle Ages were not "a time of ignorance, barbarism and superstition"; the Church did not place religious authority over personal experience and rational activity; and the term "Dark Ages" is rejected by modern historians.[17]

- While modern life expectancies are much higher than those in the Middle Ages and earlier,[18][19] adults in the Middle Ages did not die in their 30s on average. That was the life expectancy at birth, which was skewed by high infant and adolescent mortality. The life expectancy among adults was much higher;[20] a 21-year-old man in medieval England, for example, could expect to live to the age of 64.[21][20] However, in various places and eras, life expectancy was noticeably lower. For example, monks often died in their 20s or 30s.[22]

- There is no evidence that Viking warriors wore horns on their helmets; this would have been impractical in battle.[23][24]

- Vikings did not drink out of the skulls of vanquished enemies. This was based on a mistranslation of the skaldic poetic use of ór bjúgviðum hausa (branches of skulls) to refer to drinking horns.[25]

- Vikings did not name Iceland "Iceland" as a ploy to discourage oversettlement. According to the Sagas of Icelanders, Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson saw icebergs on the island when he traveled there, and named the island after them.[26] Popular legend holds that Greenland was named in the hopes of attracting settlers.[27]

- In the tale of King Canute and the tide, the king did not command the tide to reverse in a fit of delusional arrogance. According to the story, his intent was to prove a point that no man is all-powerful, and that all people must bend to forces beyond their control, such as the tides.[28]

- There is no evidence that iron maidens were used for torture, or even yet invented, in the Middle Ages. Instead they were pieced together in the 18th century from several artifacts found in museums, arsenals and the like to create spectacular objects intended for commercial exhibition.[29]

- Spiral staircases in castles were not designed in a clockwise direction to hinder right-handed attackers.[30][31] While clockwise spiral staircases are more common in castles than anti-clockwise, they were even more common in medieval structures without a military role, such as religious buildings.[32]

- The plate armor of European soldiers did not stop soldiers from moving around or necessitate a crane to get them into a saddle. They needed to be able to fight on foot in case they could not ride their horse and could mount and dismount without help.[33] However, armor used in tournaments in the late Middle Ages was significantly heavier than that used in warfare.[34]

- Whether chastity belts, devices designed to prevent women from having sexual intercourse, were invented in medieval times is disputed by modern historians. Most existing chastity belts are now thought to be deliberate fakes from the 19th century.[35]

- Medieval European scholars did not believe the Earth was flat. Scholars have known the Earth is spherical since at least the sixth century BCE.[36]

- Medieval cartographers did not regularly write "here be dragons" on their maps. The only maps from this era that have the phrase inscribed on them are the Hunt-Lenox Globe and the Ostrich Egg Globe, next to a coast in Southeast Asia for both of them. Maps in this period did occasionally have illustrations of mythical or real animals.[37]

- Christopher Columbus' efforts to obtain support for his voyages were not hampered by belief in a flat Earth, but by valid worries that the East Indies were farther than he realized.[38] In fact, Columbus grossly underestimated the Earth's circumference because of two calculation errors.[39] The myth that Columbus proved the Earth was round was propagated by authors like Washington Irving in A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus.[36]

- Columbus was not the first European to visit the Americas:[40] Leif Erikson, and possibly other Vikings before him, explored Vinland, an area of coastal North America. Ruins at L'Anse aux Meadows prove that at least one Norse settlement was built in Newfoundland, confirming a story in the Saga of Erik the Red.

Early modern

[edit]- The Mexica people of the Aztec Empire did not mistake Hernán Cortés and his landing party for gods during Cortés' conquest of the empire. This notion came from Francisco López de Gómara, who never went to Mexico and concocted the myth while working for the retired Cortés in Spain years after the conquest.[41]

- The elite of the Dutch Golden Age wore black clothes primarily as a status symbol rather than out of Puritan self-restraint. The clothes attracted status from the difficulty of the dyeing process and the cost of elaborate embellishments.[42][43]

- The early settlers (commonly known as Pilgrims) of the Plymouth Colony in North America usually did not wear all black, and their capotains (hats) did not include buckles. Instead, their fashion was based on that of the late Elizabethan era.[44] The traditional image was formed in the 19th century when buckles were a kind of emblem of quaintness.[45] (The Puritans, who settled in the adjacent Massachusetts Bay Colony shortly after the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth, did frequently wear all black.)[46]

- Shah Jahan, the Indian Mughal Emperor who commissioned the Taj Mahal, did not cut off the hands of the rumored 40,000 workers or lead designers so as to not allow the construction of another monument more beautiful than the Taj Mahal. This is an urban myth that goes back to the 1960s.[47][48][49]

- The story that Isaac Newton was inspired to research the nature of gravity when an apple fell on his head is almost certainly apocryphal. All Newton himself ever said was that the idea came to him as he sat "in a contemplative mood" and "was occasioned by the fall of an apple".[50]

- People accused of witchcraft were not burned at the stake during the Salem witch trials. Of the accused, nineteen people convicted of witchcraft were executed by hanging, at least five died in prison, and one man was pressed to death by stones while trying to extract a confession from him.[51]

- Marie Antoinette did not say "let them eat cake" when she heard that the French peasantry were starving due to a shortage of bread. The phrase was first published in Rousseau's Confessions, written when Marie Antoinette was only nine years old and not attributed to her, just to "a great princess". It was first attributed to her in 1843.[52]

- George Washington did not have wooden teeth. His dentures were made of lead, gold, hippopotamus ivory, the teeth of various animals, including horse and donkey teeth,[53][54] and human teeth, possibly bought from slaves or poor people.[55][56] Because ivory teeth quickly became stained, they may have had the appearance of wood to observers.[54]

- The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence did not occur on July 4, 1776. After the Second Continental Congress voted to declare independence on July 2, the final language of the document was approved on July 4, and it was printed and distributed on July 4–5.[57] However, the actual signing occurred on August 2, 1776.[58]

- Benjamin Franklin did not propose that the wild turkey be used as the symbol for the United States instead of the bald eagle. While he did serve on a commission that tried to design a seal after the Declaration of Independence, his proposal was an image of Moses. His objections to the eagle as a national symbol and preference for the turkey were stated in a 1784 letter to his daughter in response to the Society of the Cincinnati's use of the former; he never expressed that sentiment publicly.[59]

- There was never a bill to make German the official language of the United States that was defeated by one vote in the House of Representatives, nor has one been proposed at the state level. In 1794, a petition from a group of German immigrants was put aside on a procedural vote of 42 to 41, that would have had the government publish some laws in German. This was the basis of the Muhlenberg legend, named after the Speaker of the House at the time, Frederick Muhlenberg, who was of German descent and abstained from this vote.[60]

Modern

[edit]

- Napoleon Bonaparte was not especially short for a Frenchman of his time. He was the height of an average French male in 1800, but short for an aristocrat or officer.[61] After his death in 1821, the French emperor's height was recorded as 5 feet 2 inches in French feet, which in English measurements is 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m).[62][63]

- The nose of the Great Sphinx of Giza was not shot off by Napoleon's troops during the French campaign in Egypt (1798–1801); it has been missing since at least the 10th century.[64]

- Cinco de Mayo is not Mexico's Independence Day, but the celebration of the Mexican Army's victory over the French in the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862. Mexico's Declaration of Independence from Spain in 1810 is celebrated on September 16.[65]

- Victorian-era doctors did not invent the vibrator to cure female "hysteria" by triggering orgasm.[66]

- Albert Einstein did not fail mathematics classes in school. Einstein remarked, "I never failed in mathematics.... Before I was fifteen I had mastered differential and integral calculus."[67] Einstein did, however, fail his first entrance exam into the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School (ETH) in 1895, when he was two years younger than his fellow students, but scored exceedingly well in the mathematics and science sections, and then passed on his second attempt.[68]

- Alfred Nobel did not omit mathematics in the Nobel Prize due to a rivalry with mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler, as there is little evidence the two ever met, nor was it because Nobel's spouse had an affair with a mathematician, as Nobel was never married. The more likely explanation is that Nobel believed mathematics was too theoretical to benefit humankind, as well as his personal lack of interest in the field.[69] (See also: Nobel Prize controversies)

- Grigori Rasputin was not assassinated by being fed cyanide-laced cakes and wine, shot multiple times, and then thrown into the Little Nevka river when he survived the former two. A contemporary autopsy reported that he was just killed with gunshots. A sensationalized account from the memoirs of co-conspirator Prince Felix Yusupov is the only source of this story.[70][71][72]

- The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini did not "make the trains run on time". Much of the repair work had been performed before he and the Fascist Party came to power in 1922. Moreover, the Italian railways' supposed adherence to timetables was more propaganda than reality.[73]

- There is no evidence of Polish cavalry mounting a brave but futile charge against German tanks using lances and sabers during the German invasion of Poland in 1939. This story may have originated from German propaganda efforts following the charge at Krojanty.[74]

- The Nazis did not use the term "Nazi" to refer to themselves. The full name of the Nazi Party was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers' Party), and members referred to themselves as Nationalsozialisten (National Socialists) or Parteigenossen (party comrades). The term "Nazi" was in use prior to the rise of the Nazis as a colloquial and derogatory word for a backwards farmer or peasant. Opponents of the National Socialists abbreviated their name as "Nazi" for derogatory effect and the term was popularized by German exiles outside of Germany.[75]

- During the occupation of Denmark by the Nazis during World War II, King Christian X of Denmark did not thwart Nazi attempts to identify Jews by wearing a yellow star himself. Jews in Denmark were never forced to wear the Star of David. The Danish resistance did help most Jews flee the country before the end of the war.[76]

- Not all skinheads are white supremacists; many skinheads identify as left-wing or apolitical, and many oppose racism, such as the Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice. Originating from the 1960s British working class, many of its initial adherents were black and West Indian; it became associated with white supremacy in the 1970s as a result of far-right groups like the National Front recruiting from the subculture for grassroot support.[77][78][79][80]

United States

[edit]

- Betsy Ross did not design or make the first official U.S. flag, despite it being widely known as the Betsy Ross flag. The claim was first made by her grandson a century later.[81]

- Abraham Lincoln did not write his Gettysburg Address speech on the back of an envelope on his train ride to Gettysburg. The speech was substantially complete before Lincoln left Washington for Gettysburg.[82][83]

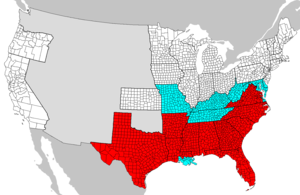

- The Emancipation Proclamation did not free all slaves in the United States; the Proclamation applied in the ten states that were still in rebellion in 1863, and thus did not cover the nearly five hundred thousand slaves in the slaveholding border states that had not seceded.[84][85][86] (See also: Abolition of slavery timeline)

- Likewise, the June 19, 1865 order celebrated annually as "Juneteenth" only applied in Texas, not the United States at large. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified and proclaimed in December 1865, was the article that banned slavery nationwide except as punishment for a crime.[84][85]

- The Alaska Purchase was generally viewed as positive or neutral in the United States, both among the public and the press. The opponents of the purchase who characterized it as "Seward's Folly", alluding to William H. Seward, the Secretary of State who negotiated it, represented a minority opinion at the time.[87][88]

- Cowboy hats were not initially popular in the Western American frontier, with derby or bowler hats being the typical headgear of choice.[89] Heavy marketing of the Stetson "Boss of the Plains" model in the years following the American Civil War was the primary driving force behind the cowboy hat's popularity, with its characteristic dented top not becoming standard until near the end of the 19th century.[90]

- The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was not caused by Mrs. O'Leary's cow kicking over a lantern. A newspaper reporter later admitted to having invented the story to make colorful copy.[91]

- There is no evidence that Frederic Remington, on assignment to Cuba in 1897, telegraphed William Randolph Hearst: "There will be no war. I wish to return," nor that Hearst responded: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war". The anecdote was originally included in a book by James Creelman and probably never happened.[92]

- The electrocution of Topsy the Elephant was not an anti-alternating current demonstration organized by Thomas A. Edison during the war of the currents. Edison was never at Luna Park, and the electrocution of Topsy took place ten years after the war of currents.[93] This myth may stem from the fact that the recording of the event was produced by the Edison film company.

- Mary Mallon, known as "Typhoid Mary", testified at her 1909 trial that she did not believe she was contagious while an asymptomatic carrier of the bacteria Salmonella typhi.[94] She later infected many others, while using fake names and evading health authorities.

- Immigrants' last names were not Americanized (voluntarily, mistakenly, or otherwise) upon arrival at Ellis Island. Officials there kept no records other than checking ship manifests created at the point of origin, and there was simply no paperwork that would have let them recast surnames, let alone any law. At the time in New York, anyone could change the spelling of their name simply by using that new spelling.[95] These names are often referred to as an "Ellis Island Special".

- Prohibition did not make drinking alcohol illegal in the United States. The Eighteenth Amendment and the subsequent Volstead Act prohibited the production, sale, and transport of "intoxicating liquors" within the United States, but their possession and consumption were never outlawed.[96]

- Distraught stockbrokers did not jump to their deaths in large numbers after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Although extensively reported by the news media, the phenomenon was limited in number and the overall suicide rate following the 1929 crash did not increase.[97]

- There was no widespread outbreak of panic across the United States in response to Orson Welles' 1938 radio adaptation of H.G. Wells' The War of the Worlds. Only a very small share of the radio audience was listening to it, but newspapers, being eager to discredit radio as a competitor for advertising, played up isolated reports of incidents and increased emergency calls. Both Welles and CBS, which had initially reacted apologetically, later came to realize that the myth benefited them and actively embraced it in later years.[98]

- American pilot Kenneth Arnold did not coin the term flying saucer; he did not use that phrase when describing his 1947 UFO sighting at Mount Rainier, Washington. The East Oregonian, the first newspaper to report on the incident, merely quoted him as saying the objects "flew like a saucer" and were "flat like a pie pan".[99][100][101][102]

- U.S. Senator George Smathers never gave a speech to a less-educated audience describing his opponent, Claude Pepper, as an "extrovert" whose sister was a "thespian", in the apparent hope they would confuse them with similar-sounding words like "pervert" and "lesbian". Smathers offered US$10,000 to anyone who could prove he had made the speech; it was never claimed.[103]

- Dwight D. Eisenhower did not order the construction of the Interstate Highway System for the sole purpose of evacuating cities in the event of nuclear warfare. While military motivations were present, the primary motivations were civilian.[104][105]

- Rosa Parks was not sitting in the front ("white") section of the bus during the event that made her famous and incited the Montgomery bus boycott. Rather, she was sitting in the front of the back ("colored") section of the bus, where African Americans were expected to sit, and rejected an order from the driver to vacate her seat in favor of a white passenger when the "white" section of the bus had become full.[106]

- The African-American intellectual and activist W. E. B. Du Bois did not renounce his U.S. citizenship while living in Ghana shortly before his death.[107][108] In early 1963, his membership in the Communist Party and support for the Soviet Union led the U.S. State Department not to renew his passport while he was already in Ghana. After leaving the embassy, he stated his intention to renounce his citizenship in protest, but while he took Ghanaian citizenship, he never actually renounced his American citizenship.[109][107]

- US President John F. Kennedy's words "Ich bin ein Berliner" are standard German for "I am a Berliner (citizen of Berlin)."[110] It is not true that by using the indefinite article ein, he changed the meaning of the sentence from the intended "I am a citizen of Berlin" to "I am a Berliner", a Berliner being a type of German pastry, similar to a jelly doughnut, amusing Germans.[111] Furthermore, the pastry, which is known by many names in Germany, was not then — nor is it now — commonly called "Berliner" in the Berlin area.[112]

- When Kitty Genovese was murdered outside her apartment in 1964, there were not 38 neighbors standing idly by and watching who failed to call the police until after she was dead, as was initially reported[113] to widespread public outrage that persisted for years and even became the basis of a theory in social psychology. In fact, witnesses only heard brief portions of the attack and did not realize what was occurring, and only six or seven actually saw anything. One witness, who had called the police, said when interviewed by officers at the scene, "I didn't want to get involved",[114] an attitude later attributed to all the neighbors.[115]

- While it was praised by one architectural magazine before it was built as "the best high apartment of the year", the Pruitt–Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri never won any awards for its design.[116] The architectural firm that designed the buildings did win an award for an earlier St. Louis project, which may have been confused with Pruitt–Igoe.[117]

- There is little contemporary documentary evidence for the notion that US Vietnam veterans were spat upon by anti-war protesters upon return to the United States. This belief was detailed in some biographical accounts and was later popularized by films such as Rambo.[118][119][120]

- Women did not burn their bras outside the Miss America contest in 1969 as a protest in support of women's liberation. They did symbolically throw bras in a trash can, along with other articles seen as emblematic of women's position in American society such as mops, make-up, and high-heeled shoes. The myth of bra burning came when a journalist hypothetically suggested that women may do so in the future, as men of the era burned their draft cards.[121]

- The American space program in the 1960s never had a wide base of public support and didn't unify America. Belief that the Apollo program was worth the time and money invested peaked at 51% for a few months after the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, and otherwise had fluctuated between 35-45% support.[122][123][124]

- Despite popularizing the phrase "drinking the Kool-Aid",[125] Kool-Aid was not used for the potassium cyanide-fruit punch mix ingested as part of the Jonestown massacre.[126] A similar product, Flavor-Aid, was used.[127][128]

References

[edit]- ^ a. Shaw, Johnathan (July–August 2003). "Who Built the Pyramids?". Harvard Magazine. Archived from the original on March 19, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

b. "Egypt tombs suggest pyramids not built by slaves". Reuters. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on December 20, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

c. Weiss, Daniel (July–August 2022). "Journeys of the Pyramid Builders". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2022.Based on the contents of the papyri, Tallet believes that at least some workers in the time of Khufu were highly skilled and well rewarded for their labor, contradicting the popular notion that the Great Pyramid was built by masses of oppressed slaves.

- ^ a b Watterson, Barbara (1997). "The Era of Pyramid-builders". The Egyptians. Blackwell. p. 63.

Herodotus claimed that the Great Pyramid at Giza was built with the labour of 100,000 slaves working in three-monthly shifts, a charge that cannot be substantiated. Much of the non-skilled labour on the pyramids was undertaken by peasants working during the Inundation season when they could not farm their lands. In return for their services they were given rations of food, a welcome addition to the family diet.

- ^ Kratovac, Katarina (January 12, 2010). "Egypt: New Find Shows Slaves Didn't Build Pyramids". U.S. News. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ Casson, Lionel (1966). "Galley Slaves". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 97: 35–36. doi:10.2307/2936000. JSTOR 2936000.

- ^ Sargent, Rachel L (July 1927). "The Use of Slaves by the Athenians in Warfare II. In Warfare by Sea" (PDF). Classical Philology. 22 (3): 264–279. doi:10.1086/360910. JSTOR 262754 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Unger, Richard (1980). The ship in the medieval economy, 600-1600. London: Croom Helm. p. 37. ISBN 0-85664-949-X.

- ^ a. James Hamilton-Paterson, Carol Andrews, Mummies: Death and Life in Ancient Egypt, p. 191, Collins for British Museum Publications, 1978, ISBN 978-0-00-195532-5

b. Charlotte Booth, The Boy Behind the Mask, p. xvi, Oneword, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

c. Richard Cavendish, "Tutankhamun's Curse?", History Today 64:3 (3 March 2014 Archived April 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine) - ^ a. Neer, Richard (2012). Art and Archaeology of the Greek World. Thames and Hudson. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-500-05166-5.

"...popular associations of the eruption with a legend of Atlantis should be dismissed...nor is there good evidence to suggest that the eruption...brought about the collapse of Minoan Crete

b. Manning, Stuart (2012). "Eruption of Thera/Santorini". In Cline, Eric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford University Press. pp. 457–454. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199873609.013.0034. ISBN 978-0-19-987360-9.Marinatos (1939) famously suggested that the eruption might even have caused the destruction of Minoan Crete (also Page 1970). Although this simple hypothesis has been negated by the findings of excavation and other research since the late 1960s... which demonstrate that the eruption occurred late in the Late Minoan IA ceramic period, whereas the destructions of the Cretan palaces and so on are some time subsequent (late in the following Late Minoan IB ceramic period)

- ^ Sparkes A.W. (1988). "Idiots, Ancient and Modern". Australian Journal of Political Science. 23: 101–102. doi:10.1080/00323268808402051.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. Archived August 8, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Winkler, Martin M. (2009). The Roman Salute: Cinema, History, Ideology. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-0864-9. p. 55

- ^ a b McKeown, J.C. (2010). A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the World's Greatest Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 153–54. ISBN 978-0-19-539375-0.

- ^ Fass, Patrick (1994). Around the Roman Table. University of Chicago Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-226-23347-5. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ a. Ridley, R.T. (1986). "To Be Taken with a Pinch of Salt: The Destruction of Carthage". Classical Philology. 81 (2): 140–146. doi:10.1086/366973. JSTOR 269786. S2CID 161696751.: "a tradition in Roman history well known to most students"

b. Stevens, Susan T. (1988). "A Legend of the Destruction of Carthage". Classical Philology. 83 (1): 39–41. doi:10.1086/367078. JSTOR 269635. S2CID 161764925.

c. Visona, Paolo (1988). "Passing the Salt: On the Destruction of Carthage Again". Classical Philology. 83 (1): 41–42. doi:10.1086/367079. JSTOR 269636. S2CID 162289604.: "this story... had already gained widespread currency"

d. Warmington, B.H. (1988). "The Destruction of Carthage: A Retractatio". Classical Philology. 83 (4): 308–10. doi:10.1086/367123. JSTOR 269510. S2CID 162850949.: "the frequently repeated story" - ^ "[A mother in the 1st century AD] could not survive the trauma of a Caesarean" Oxford Classical Dictionary, Third Edition, "Childbirth"

- ^ Wanjek, Christopher (April 7, 2003). Bad Medicine: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Distance Healing to Vitamin O. John Wiley & Sons. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-471-46315-3.

- ^ a. Lindberg, David C. (2003). "The Medieval Church Encounters the Classical Tradition: Saint Augustine, Roger Bacon, and the Handmaiden Metaphor". In Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (eds.). When Science & Christianity Meet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 8.

b. Grant, Edward (2001). God and Reason in the Middle Ages. Cambridge. p. 9.

c. Peters, Ted (2005). "Science and Religion". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). Thomson Gale. p. 8182.

d. Snyder, Christopher A. (1998). An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons A.D. 400–600. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. xiii–xiv. ISBN 978-0-271-01780-8. - ^ Bitel LM (2002-10-24). Women in Early Medieval Europe, 400-1100. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59773-9.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2019" (PDF). Population Division. U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- ^ a b Wanjek, Christopher (2002). Bad Medicine: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Distance Healing to Vitamin O. Wiley. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-471-43499-3.

- ^ ""Expectations of Life" by H.O. Lancaster as per". Archived from the original on September 4, 2012.

- ^ Scott, Robert A. (October 4, 2011). Miracle Cures: Saints, Pilgrimage, and the Healing Powers of Belief (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-520-27134-0.

- ^ Kahn, Charles (2005). World History: Societies of the Past. Portage & Main Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-55379-045-7.

- ^ "Viking helmets". National Museum of Denmark.

In a battle situation, horns on a helmet would get in the way.

- ^ E. W. Gordon, Introduction to Old Norse (2nd edition, Oxford 1962) pp. lxix–lxx.

- ^ Evans, Andrew (June 2016). "Is Iceland Really Green and Greenland Really Icy?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016.

- ^ a. Eirik the Red's Saga. Gutenberg.org. March 8, 2006. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

b. "How Greenland Got Its Name". The Ancient Standard. December 17, 2010. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2020..

c. Grove, Jonathan (2009). "The place of Greenland in medieval Icelandic saga narrative". Journal of the North Atlantic. 2: 30–51. doi:10.3721/037.002.s206. S2CID 163032041. Archived from the original on April 11, 2012. - ^ "Is King Canute misunderstood?". BBC. May 26, 2011. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014.

- ^ Schild, Wolfgang (2000). Die eiserne Jungfrau. Dichtung und Wahrheit (Schriftenreihe des Mittelalterlichen Kriminalmuseums Rothenburg o. d. Tauber Nr. 3). Rothenburg ob der Tauber: Mittelalterl. Kriminalmuseum.

- ^ Guy, Neil (2011–2012). "The Rise of the Anticlockwise Newel Stair" (PDF). The Castle Studies Group Journal. 25: 114, 163. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Wright, James (October 9, 2019). Guest Post: Busting Mediaeval Building Myths: Part One. History... the interesting bits!. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Ryder, Charles (2011). The spiral stair or vice: its origins, role and meaning in medieval stone castles (PhD). University of Liverpool. p. 294. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Breiding, Dirk. "Department of Arms and Armor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ "Cranes hoisting armored knights". Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Keyser, Linda Migl (2008). "The Medieval Chastity Belt Unbuckled". In Harris, Stephen J.; Grigsby, Bryon L. (eds.). Misconceptions About the Middle Ages. Routledge.

- ^ a b "Busting a myth about Columbus and a flat Earth". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ a. Meyer, Robinson (December 12, 2013). "No Old Maps Actually Say 'Here Be Dragons'". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

b. Van Duzer, Chet (June 4, 2014). "Bring on the Monsters and Marvels: Non-Ptolemaic Legends on Manuscript Maps of Ptolemy's Geography". Viator. 45 (2): 303–334. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.1.103923. ISSN 0083-5897.

c. Kim, Meeri (August 19, 2013). "Oldest globe to depict the New World may have been discovered". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2022.The only other map or globe on which this specific phrase appears is what can arguably be called the egg's twin: the copper Hunt-Lenox Globe, dated around 1510 and housed by the Rare Book Division of the New York Public Library.

- ^ Louise M. Bishop (2010). "The Myth of the Flat Earth". In Stephen Harris; Bryon L. Grigsby (eds.). Misconceptions about the Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-98666-7. Archived from the original on August 8, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Columbus's Geographical Miscalculations". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. October 9, 2012. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ a. Eviatar Zerubavel (2003). Terra cognita: the mental discovery of America. Transaction Publishers. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-7658-0987-2. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

b. Sale, Kirkpatrick (1991). The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy. Plume. pp. 204–09. ISBN 978-1-84511-154-0 – via Google Books. - ^ Wills, Matthew (January 17, 2020). The Mexica Didn't Believe the Conquistadors Were Gods Archived April 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. JSTOR. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Pound, Cath (March 14, 2018). "When the Old Masters Were the P.R. Agents of the Rich and Powerful". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (June 22, 2007). "The old black". The Guardian. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ "Plymouth Colony Clothing". Web.ccsd.k12.wy.us. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ a. Schenone, Laura (2004). A Thousand Years Over A Hot Stove: A History Of American Women Told Through Food, Recipes, And Remembrances. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-393-32627-7.

b. Wilson, Susan (2000). Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-618-05013-0. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2021 – via Google Books. - ^ Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice (July 22, 2018). "What Did the Pilgrims Wear?". History of Massachusetts Blog. Rebecca Beatrice Brooks. Archived from the original on November 10, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Mehta, Archit (2021-12-24). "Fact-check: Did Shah Jahan chop off the hands of Taj Mahal workers?". Alt News. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ Beg, M. Saleem (2022-03-08). "Debunking an urban myth about Taj Mahal". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ S. Sharma, Manimugdha (2017-10-22). "Busting the Taj fake news". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ "Newton's apple: The real story". New Scientist. January 18, 2010. Archived from the original on January 21, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ a. Rosenthal, Bernard (1995). Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692. Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-521-55820-4. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

b. Adams, Gretchen (2010). The Specter of Salem: Remembering the Witch Trials in Nineteenth-Century America. ReadHowYouWant.com. p. xxii. ISBN 978-1-4596-0582-4. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2016 – via Google Books.

c. Kruse, Colton (March 22, 2018). "Salem Never Burned Any Witches At The Stake". Ripley's Believe It or Not!. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022. - ^ "Top 5 Marie Antoinette Scandals". history.howstuffworks.com. September 2, 2008. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Washington's False Teeth Not Wooden". NBC News. January 27, 2005. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Etter, William M. "George Washington's Teeth Myth". www.mountvernon.org. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Thompson, Mary V. "The Private Life of George Washington's Slaves". PBS. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "Teeth". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ "Declaration of Independence – A History". archives.gov. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Crabtree, Steve (July 6, 1999). "New Poll Gauges Americans' General Knowledge Levels". Gallup News Service. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ a. Lund, Nicholas (November 21, 2013). "Did Benjamin Franklin Really Say the National Symbol Should Be the Turkey?". Slate. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

b. McMillan, Joseph (May 18, 2007). "The Arms of the United States: Benjamin Franklin and the Turkey". American Heraldry Society. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2013. - ^ a. Sick, Bastian (2004). Der Dativ ist dem Genetiv sein Tod (in German). Kiepenheuer & Witsch. pp. 131–135. ISBN 978-3-462-03448-6 – via Internet Archive.

b. "Willi Paul Adams: The German Americans. Chapter 7: German or English". Archived from the original on June 24, 2010.

c. "The German Vote". Snopes. July 9, 2007. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2013. - ^ a. Owen Connelly (2006). Blundering to Glory: Napoleon's Military Campaigns. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7425-5318-7.

b. Evans, Rod L. (2010). Sorry, Wrong Answer: Trivia Questions That Even Know-It-Alls Get Wrong. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-399-53586-4. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

c. "Forget Napoleon – Height Rules". CBS News. February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2011. - ^ a. "Fondation Napoléon". Napoleon.org. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

b. "La taille de Napoléon" (in French). Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2010. - ^ "Napoleon's Imperial Guard". Archived from the original on April 27, 2014.

- ^ a. "The nose of the Great Sphinx". britannica.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

b. Feder, Kenneth L. (2010-10-11). Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37919-2. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

c. Zivie-Coche, Christiane (2002). Sphinx: History of a Monument. Cornell University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8014-3962-9. - ^ a. Lovgren, Stefan (May 5, 2006). "Cinco de Mayo, From Mexican Fiesta to Popular U.S. Holiday". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007.

b. Lauren Effron (May 5, 2010). "Cinco de Mayo: NOT Mexico's Independence Day". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2011. - ^ a. "Hysteria". Welcome Collection. August 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

b. King, Helen (2011). "Galen and the widow. Towards a history of therapeutic masturbation in ancient gynaecology". Eugesta, Journal of Gender Studies in Antiquity: 227–31.

c. "Victorian-Era Orgasms and the Crisis of Peer Review". The Atlantic. September 6, 2018. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

d. "Why the Movie "Hysteria" Gets Its Vibrator History Wrong". Dildographer. May 4, 2012. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

e. King, Helen (2011). "Galen and the widow. Towards a history of therapeutic masturbation in ancient gynaecology". Eugesta, Journal of Gender Studies in Antiquity: 206–08.

f. "Buzzkill: Vibrators and the Victorians (NSFW)". The Whores of Yore. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

g. Riddell, Fern (November 10, 2014). "No, no, no! Victorians didn't invent the vibrator". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2018. - ^ a. Isaacson, Walter (April 5, 2007). "Making the Grade". Time. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Kruszelnicki, Karl (June 22, 2004). "Einstein Failed School". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ a. López-Ortiz, Alex (February 20, 1998). "Why is there no Nobel in mathematics?". University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

b. Mikkelson, David (October 4, 2013). "No Nobel Prize for Math". Snopes. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

c. Firaque, Kabir (October 16, 2019). "Explained: Why is there no mathematics Nobel? The theories, the facts, the myths". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2022. - ^ Harris, Carolyn (December 27, 2016). "The Murder of Rasputin, 100 Years Later". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on October 15, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ "How was Russian mystic Rasputin murdered?". BBC. December 31, 2016. Archived from the original on October 31, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Douglas (2016). "A Cowardly Crime". Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 590–592. ISBN 978-0-374-71123-8.

- ^ Cathcart, Brian (April 3, 1994). "Rear Window: Making Italy work: Did Mussolini really get the trains running on time". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ a. Ankerstjerne, Christian. "The myth of Polish cavalry charges". Panzerworld. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

b. "The Mythical Polish Cavalry Charge". Polish American Journal. Polamjournal.com. July 2008. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2012. - ^ Nazi. In: Friedrich Kluge, Elmar Seebold: Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. 24. Auflage, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York 2002, ISBN 3-11-017473-1 (Online Etymology Dictionary: Nazi Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ a. Vilhjálmur Örn Vilhjálmsson. "The King and the Star – Myths created during the Occupation of Denmark" (PDF). Danish institute for international studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

b. "Some Essential Definitions & Myths Associated with the Holocaust". Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies – University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

c. "King Christian and the Star of David". The National Museum of Denmark. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2017. - ^ a. Craig, Laura; Young, Kevin (2008). "Beyond White Pride: Identity, Meaning and Contradiction in the Canadian Skinhead Subculture*". Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie. 34 (2): 175–206. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618x.1997.tb00206.x. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

b. Borgeson, Kevin; Valeri, Robin (Fall 2005). "Examining Differences in Skinhead Ideology and Culture Through an Analysis of Skinhead Websites". Michigan Sociological Review. 19: 45–62. JSTOR 40969104.

c. Lambert, Chris (November 12, 2017). "'Black Skinhead': The politics of New Kanye". Daily Dot. Retrieved July 2, 2022."Skinhead" was a term originally used to describe a 1960s British working-class subculture that revolved around fashion and music and that would heavily inspire the punk rock scene. While it has harmless roots, the skinhead movement fell into polemic politics. Nowadays, it's popularly associated with neo-Nazis, despite having split demographics of far-right, far-left, and apolitical.

- ^ Brown, Timothy S. (January 1, 2004). "Subcultures, Pop Music and Politics: Skinheads and "Nazi Rock" in England and Germany". Journal of Social History. 38 (1): 157–178. doi:10.1353/jsh.2004.0079. JSTOR 3790031. S2CID 42029805.

- ^ Cotter, John M. (1999). "Sounds of hate: White power rock and roll and the neo-nazi skinhead subculture". Terrorism and Political Violence. 11 (2): 111–140. doi:10.1080/09546559908427509. ISSN 0954-6553.

- ^ Shaffer, Ryan (2013). "The soundtrack of neo-fascism: youth and music in the National Front". Patterns of Prejudice. 47 (4–5): 458–482. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2013.842289. ISSN 0031-322X. S2CID 144461518.

- ^ Marc Leepson, "Five myths about the American flag" Archived 2017-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, June 12, 2011, p. B2.

- ^ "The Lincoln Presidency: Last Full Measure of Devotion". rmc.library.cornell.edu.

- ^ Green, Joey (2005). Contrary to Popular Belief: More than 250 False Facts Revealed. Broadway. ISBN 978-0-7679-1992-0.

- ^ a b Stewart, Alicia W. (1 January 2013). "150 years later, myths persist about the Emancipation Proclamation". CNN. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ a b Berlin, Ira; Fields, Barbara J.; Glymph, Thavolia; Reidy, Joseph P.; Rowland, Leslie S., eds. (1985). Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867: Series 1, Volume 1: The Destruction of Slavery. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-521-22979-1.

- ^ Foner, Eric (2010). The fiery trial: Abraham Lincoln and American slavery. New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-393-06618-0. OCLC 601096674.

- ^ a. Haycox, Stephen (1990). "Haycox, Stephen. "Truth and Expectation: Myth in Alaska History". Northern Review. 6. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

b. Welch, Richard E. Jr. (1958). "American Public Opinion and the Purchase of Russian America". American Slavic and East European Review. 17 (4): 481–94. doi:10.2307/3001132. JSTOR 3001132.

c. Howard I. Kushner, "'Seward's Folly'?: American Commerce in Russian America and the Alaska Purchase". California Historical Quarterly (1975): 4–26. JSTOR 25157541.

d. "Biographer calls Seward's Folly a myth". The Seward Phoenix LOG. April 3, 2014. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

e. Professor Preston Jones (Featured Speaker) (July 9, 2015). Founding of Anchorage, Alaska (Adobe Flash). C-SPAN. Retrieved December 22, 2017. - ^ Cook, Mary Alice (Spring 2011). "Manifest Opportunity: The Alaska Purchase as a Bridge Between United States Expansion and Imperialism" (PDF). Alaska History. 26 (1): 1–10.

- ^ "The Hat That Won the West". Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Snyder, Jeffrey B. (1997) Stetson Hats and the John B. Stetson Company 1865–1970. p. 50 ISBN 978-0-7643-0211-4

- ^ "The O'Leary Legend". Chicago History Museum. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ^ a. Campbell, W. Joseph (2010). Getting it Wrong: Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 9–25. ISBN 978-0-520-26209-6 – via Internet Archive.

b. Campbell, W. Joseph (2003). Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies. Praeger. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-275-98113-6. - ^ "Did Edison really electrocute Topsy the Elephant". The Edison Papers. October 28, 2016. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013 – via Rutgers University.

- ^ Foss, Katherine (April 24, 2020). "#TyphoidMary – now a hashtag – was a maligned immigrant who got a bum rap". The Conversation.

- ^ "Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island (and One That Was)". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015.

- ^ "Prohibition | Definition, History, Eighteenth Amendment, & Repeal". britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ "Market Crash Eexacts a Toll in Suicides". Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ a. Pooley, Jefferson; Socolow, Michael (October 28, 2013). "The Myth of the War of the Worlds Panic". Slate. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

b. Campbell, W. Joseph (2010). Getting it wrong: ten of the greatest misreported stories in American Journalism. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 26–44. ISBN 978-0-520-26209-6 – via Google Books. - ^ Garber, Megan (June 15, 2014). "The Man Who Introduced the World to Flying Saucers". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Lacitis, Eric (June 24, 2017). "'Flying saucers' became a thing 70 years ago Saturday with sighting near Mount Rainier". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Arnold, Kenneth (June 26, 1947). "12:15 news" (Radio). Interviewed by Smith, Ted. Pendleton, Oregon: KWRC.

- ^ {{#invokecite news ||last1=Meyer |first1=Dave |title=64th anniversary of flying saucers at Mt. Rainier |url=https://www.knkx.org/other-news/2011-06-24/64th-anniversary-of-flying-saucers-at-mt-rainier |access-date=18 July 2024 |work=KNKX Public Radio |date=24 June 2011 |language=en |quote=Arnold described the shiny objects as 'something like a pie plate that was cut in half with a sort of a convex triangle in the rear' and that they flew 'like a saucer if you skipped it across the water.' The term 'flying saucer' made it into a newspaper headline and the rest, as they say, is history.}}

- ^ a. "Florida: Anything Goes". Time. April 17, 1950. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

b. Nohlgren, Stephen (November 29, 2003). "A born winner, if not a native Floridian". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2011. - ^ "Interstate Highway System - The Myths". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Laskow, Sarah (August 24, 2015). "Eisenhower and History's Worst Cross-Country Road Trip". Slate. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "An Act of Courage, The Arrest Records of Rosa Parks". National Archives. August 15, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Bass, Amy (2009). Those about Him Remained Silent: The Battle Over W.E.B. Du Bois. University of Minnesota Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8166-4495-7.

- ^ a. "Renouncing citizenship is usually all about the Benjamins, say experts". Fox News. May 11, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

b. "Celebrities Who Renounced Their Citizenship". Huffington Post. February 1, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

c. Aberjhani, Sandra L. West (2003). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. Infobase Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4381-3017-0. - ^ Lewis, David (2009). W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography. MacMillan. p. 841. ISBN 978-0-8050-8805-2.

- ^ a. Daum, Andreas W. (2007). Kennedy in Berlin. Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–49. ISBN 978-3-506-71991-1. Archived from the original on January 21, 2023. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

b. "Gebrauch des unbestimmten Artikels (German, "Use of the indefinite article")". Canoo Engineering AG. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2010. - ^ a. Ryan, Halford Ross (1995). U.S. presidents as orators: a bio-critical sourcebook. Greenwood. pp. 219–20. ISBN 978-0-313-29059-6. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

b. "Ich bin ein Pfannkuchen. Oder ein Berliner?" [I am a jelly doughnut. Or a Berliner?] (in German). Stadtkind. August 22, 2005. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2013. - ^ Rüther, Tobias (March 5, 2019). "Essen und Sprechen Geben Sie mir ein Semmelbrötchen!". Faz.net. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Gansberg, Martin (March 27, 1964). "37 Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police" (PDF). The New York Times. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2015.

- ^ Bregman, Rutger (2020). "9". Humankind: A Hopeful History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-9896-3.

- ^ Rasenberger, Jim (October 2006). "Nightmare on Austin Street". American Heritage. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ Cendón, Sara Fernández (February 3, 2012). "Pruitt-Igoe 40 Years Later". American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

For example, Pruitt-Igoe is often cited as an AIA-award recipient, but the project never won any architectural awards.

- ^ Bristol, Katharine (May 1991). "The Pruitt–Igoe Myth" (PDF). Journal of Architectural Education. 44 (3): 168. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2010.01093.x. ISSN 1531-314X. S2CID 219542179. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

Though it is commonly accorded the epithet 'award-winning,"' Pruitt-Igoe never won any kind of architectural prize. An earlier St. Louis housing project by the same team of architects, the John Cochran Garden Apartments, did win two architectural awards. At some point this prize seems to have been incorrectly attributed to Pruitt-Igoe

- ^ Jerry Lembcke, The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory and the Legacy of Vietnam, 1998, ISBN 978-0-8147-5147-3

- ^ Greene, Bob (1989). Homecoming: When the Soldier Returned from Vietnam. G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-13386-2.

- ^ Vlieg, Heather (September 2019). "Were They Spat On? Understanding The Homecoming Experience of Vietnam Veterans". The Grand Valley Journal of History. 7 (1).

- ^ "100 Women: The truth behind the 'bra-burning' feminists". BBC News. September 6, 2018.

- ^ Novak, Matt (May 15, 2012). "How Space-Age Nostalgia Hobbles Our Future". Slate. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Saripalli, Srikanth (September 19, 2013). "To Boldly Go Nowhere, for Now". Slate. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Strauss, Mark (April 14, 2011). "Ten Enduring Myths About the U.S. Space Program". Smithsonian. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ "Kool Aid/Flavor Aid: Inaccuracies vs. Facts Part 7". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Higgins, Chris (November 8, 2012). "Stop Saying 'Drink the Kool-Aid'". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Krause, Charles A. (December 17, 1978). "Jonestown Is an Eerie Ghost Town Now". Washington Post. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

A pair of woman's eyelasses, a towel, a pair of shorts, packets of unopened Flavor-Aid lie scattered about waiting for the final cleanup that may one day return Jonestown to the tidy, if overcrowded, little community it once was.

- ^ Kihn, Martin (March 2005). "Don't Drink the Grape-Flavored Sugar Water..." Fast Company. Archived from the original on April 7, 2005. Retrieved June 20, 2022.