User:MoSalahMoProblems/OLES2128/draft

Genre Assignment of Canonical Gospels in the New Testament

[edit]

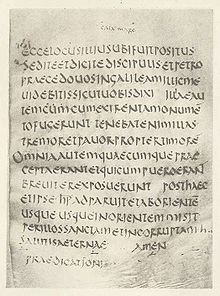

In the canon recgonized New Testament, there are four gospels, namely; Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The prior three are commonly known as the synoptic gospels and the latter John being academically recognized as a seperate text. In context with the rest of the New Testament and furthermore the Bible, these four books are commonly assigned with the name Gospel. This originates from the early manuscripts being titled "euangelion", a Koine Greek term which translates to "Good News" and thus origniates Gospel from the Old English words "God", meaning good, and "spel" meaning news.[1]

Furthermore accurately assigning a genre to the four canonical gospels has been in discussion since the berth of these texts in contemporary academia and scholarship. In most modern times due to academic works by notable Biblical studies scholar Richard Burridge, The four gospels have been gendered as Graeco-Roman Bios.

First Quest for the Historical Jesus

[edit]17th Century Academia

[edit]

The first quest for the historcial Jesus roughly began in 1778. The term "First Quest" was historically coined by the academic Albert Schweitzer in his book The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of Its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede[2]. At this time in europe scholariship in biblical studies, and more directly, gospel studies, had surpassed textual analysis and different biographies and accounts of Jesus began to arise and attempted to accurately portray who the character of Jesus was.[3] Due to a lack in historical theory advancement, gospel harmonies and other attempts to categorized the figure of Jesus Christ and accurately gender the Gospels had become sensational and glamorized by many biased academies and seminaries in Europe in order to pass an agenda around the character of Jesus Christ. Contemporary scholars such as Andreas J. Köstenberger have claimed regarding this historical apporach misleading and that the portrayal of Jesus in many of the texts depicted a Jesus "like the questers themselves" in comparison to the actual figure he was historically.[4]

18th Century Academia

[edit]This approach also came under heavy scruteny by scholars in the 19th-century such as:

David Strauss

[edit]David Strauss (1808–1874), was a forerunner for the "Historical Jesus" figure in academia. His claims where that all supernatural or mythological events where to be dismissed as anything out of the ordinary. He favoured in his book Life of Jesus that there were natural causes resulting in the miracles rather then supernatural power of Jesus.[5]

William Wrede

[edit]

William Wrede (1859–1906), applied a theory called the Messianic Secret to argue the messianic nature of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark when he is clearly never publically declaring this. Wrede uses this to present evidence of redaction by early christians to tamper with the image of the historical Jesus. William Wrede (1901), Das Messiasgeheimnis in den Evangelien, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck, OL 24396523M

Albert Schweitzer

[edit]Albert Schweitzer (1875 - 1965) (In his work The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of Its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, Schweitzer put to rest the First Conquest for the Historical Jesus based on the arguement that most works dismissing the historical Jesus as a subject text were in themselves acting as a biased subjective text applying methodology and ideals post-enlightenment, when the actual text was written in 1st-Century Syria Palaestina and cannot be apporached with the same methods of text criticism.

Second Quest for the Historical Jesus

[edit]Ernst Käsemann

[edit]When appropriately applying genre to the four canonical gospels, the Second Quest vital in outlining the non-theological reasoning behind studying the gospels as secular texts. This was pioneered by Ernst Käsemann (1906 -1998), who in 1953 delivered a lecture to a graduate audience from the University of Marburg, who were too also biblical studies scholars and effectively lectured that there was still much information within the text of the gospels that could provided more information on who that character of Jesus was.[6] This was influential in the genre application as it detached both the stigma and the tradition of gospel study from seminary and theological study and re-introduced it into popular secular study.[7]

Third Quest for the Historical Jesus

[edit]Formation

[edit]A term coined by theologian and bishop N. T. Wright,[8] the thrid quest is commonly believed to have started when Ed Sanders (1937-) released in 1977 his work Paul and Palestinian Judaism.[9] This reignited the scholarship around the gospels and was the pioneering moment for the third quest for the historical Jesus that was present in the 1970's to the 1990's. Unlike all the previous quests, the third quest was focues on approaching the gospels with the lense of the Palestinian Jew. This was an approach that most modelled that of the life of Jesus.[10]

Greaco-Roman Bios

[edit]

Graeco-Roman Bios is a literary form written to depict or narrate the stories of individuals.[11] The genre of Graeco-Roman Bios was popular and found most commonly in hellenised Ancient Rome. Usage of this literay form is common in the New Testament exclusively to the four cannonical gospels; Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. In each of these four sources the subject of the texts in which the biographies are focused on the historical figure of Jesus Christ.[12] Burridge has notably been the most popular theorist behind the genre of the Gospels and presents the arguement that however dissimilar that the synoptic gospels have with the gospel of John the strict similarities in which they all have around the consistant figure of Jesus Christ leads one to argue that they are almost inseperable when reviewing them as a individual texts and rather favour a collective review to present an accurate Historical Jesus.[13]

- ^ Burrows, Millar. “The Origin of the Term ‘Gospel.’” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 44, no. 1/2, 1925, pp. 21–33. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3260047.

- ^ Schweitzer, Albert, W Montgomery, and James M. Robinson. The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of Its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. New York: Macmillan, 1968. Print.

- ^ Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell, Westminster John Knox Press, 1998 ISBN 0664257038 pages 11-17

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, B&H Academic 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 p. 112

- ^ Strauss, David Friedrich (1835). Das leben Jesu: Kritisch bearbeitet. C.F. Osiander.

- ^ The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Jew of Nazareth. by Ben Witherington III, InterVersity Press, 1997 (second expanded edition), ISBN 0830815449 pp. 9–13

- ^ The Symbolic Jesus: Historical Scholarship, Judaism and the Construction of Contemporary Identity by William Arnal, Routledge 2005 ISBN 1845530071 pp. 41–43

- ^ Criteria for Authenticity in Historical-Jesus Research by Stanley E. Porter, Bloomsbury 2004 ISBN 0567043606 pp. 28–29

- ^ Sanders, E P. Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977. Print.

- ^ John, Jesus, and History, Volume 1: Critical Appraisals of Critical Views by Paul N. Anderson, Felix Just and Tom Thatcher 2007 ISBN 1589832930 page 127

- ^ Collins, Adela Yarbro. “Genre and the Gospels.” The Journal of Religion, vol. 75, no. 2, 1995, pp. 239–246. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1205320.

- ^ France, R.T. (2002). The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek text. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- ^ Burridge, R. (1992). Conclusions and implications. In What are the gospels: A comparison with Graeco-Roman biography (pp. 240–259). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.