User:Meeepmep/sandbox

| Operation Northwind | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

230,000 (average strength)[1] | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

11,609[2][3] killed and wounded, captured or missing[4] 7,000[5] killed and wounded | 23,000 killed, wounded, or captured[6] | ||||||

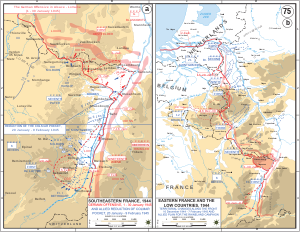

Operation Northwind (German: Unternehmen Nordwind) was the last major German offensive of World War II on the Western Front. Northwind was launched to support the German Ardennes offensive campaign in the Battle of the Bulge, which by late December 1944 had decisively turned against the German forces. It began on 31 December 1944 in Rhineland-Palatinate, Alsace and Lorraine in southwestern Germany and northeastern France, and ended on 25 January 1945. The German offensive was an operational failure, with its main objectives not achieved.

Hastily conceived as an alternative to the Ardennes Offensive or in support of it, the operation commenced well after the German offensive there had come to a halt and German forces had already largely been expelled from the Ardennes. Concurrently, Soviet forces were about to capture Warsaw and were making significant inroads into East Prussia. A substantial portion of the engagement unfolded between January 8th and 20th, 1945, in the region spanning from Hagenau to Weissenburg. However, the battles along the Vosges ridge and the establishment of a German bridgehead on the Upper Rhine had a greater influence on the course of the offensive. Ultimately, the offensive concluded following the withdrawal of American forces to the Moder line near Hagenau, and their successful repulsion of the final German attacks on January 25th.

Similar to the Ardennes Offensive, the Nordwind offensive was hampered by lack of fuel, insufficient artillery support and insufficient reconnaissance. Above all, a lack of personnel as well as stubborn Allied resistance are considered to be the decisive reasons for the failure of Nordwind. The units deployed in this section of the front, which had been weakened by the previous retreat, were inadequately staffed, a shortcoming that was only belatedly compensated for by the deployment of reserves. Operational control was made even more difficult by the fragmented command structure, as the offensive not solely under the purview of Army Group G. The 19th Army was separated from Army Group G and formed the newly established Army Group Upper Rhine commanded by Heinrich Himmler, who had no military experience or staff officer training.

Operation Nordwind is one of the lesser-known and sometimes even misrepresented major operations of the Second World War; public perception is dominated by the simultaneous battles in the Ardennes, in the Hürtgen Forest and the Vistula-Oder Offensive on the Eastern Front.

Background

[edit]On November 12, 1944, the 6th US Army Group, consisting of the 7th US Army and the French 1st Army, launched an offensive on both sides of the Vosges supported by the 3rd US Army. The Allied armies soon broke through the Saverne Pass and the Belfort Gap, reaching the Upper Rhine near Mulhouse on November 19. On November 23, they neared Strasbourg. On the direct orders of Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied units did not cross the Rhine, but drove north. In early to mid-December, they had largely pushed the German 1st Army north from Lower Alsace and pinned significant parts of the 19th Army in the Colmar Pocket. 19th Army was then separated from Army Group G on December 2nd, and transferred to the newly formed Army Group Upper Rhine. Supreme command of Army Group Upper Rhine was then given to Heinrich Himmler on December 10, Himmler bypassed typical Wehrmacht chain of command and was directly subordinate to Führer's headquarters. At the end of December 1944, after initial successes, the German Ardennes Offensive ground to a halt. In order to free up forces for an American counterattack in the Ardennes, the 7th US Army took over large parts of the 3rd US Army's sector of the front in Lower Alsace and Lorraine. With the US 7th Army stretched thin, the section thus became the weakest part of the American front. On the other hand, the German forces in the West still had several divisions available as reserves that could be deployed in mid-January 1945.

Allied planning

[edit]As the 3rd US Army was reorganizing for a counteroffensive against the Germans in the Ardennes, SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force) became aware of the challenges that faced the 6th US Army Group with its now over-extended section of the front. In a meeting on December 26, 1944, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had recently been promoted to General of the Army, informed the commander of the 6th US Army Group, Jacob L. Devers, that in order to shorten the more vulnerable front of the 6th US Army Group, he wanted it to be withdrawn from the Upper Rhine to the Vosges ridge. Neither this discussion nor SHAEF's subsequent urging were interpreted by Devers as formal commands. Devers had serious doubts about the Allied military intelligence system and SHAEF's assessment of the situation after the Ardennes fiasco, he therefore did not see a withdrawal as urgent. Devers planned a withdrawal, but did not carry it out. According to his assessment, which was also shared by the commander of the 7th US Army Alexander Patch, a German attack on the Saar was more likely. This view was reinforced by a spoiling attack there by Panzer Lehr Division in November 1944. Another possibility, considered less likely because of the terrain, was an attack along the Vosges ridge. A German attack in the Upper Rhine plain was considered implausible because of the sections of strong Maginot Line defenses held by the Americans.

For the aforementioned reasons, Patch planned a defence in depth with the following defensive lines:

1. The Maginot Line

2. Bitche – Niederbronn – Moder

3. Bitche – Ingweiler – Strasbourg

4. Eastern foothills of the Vosges

Allied forces

[edit]On paper, the Allies had fewer divisions than the Germans, but they were better manned and supplied. Levels of experience and training varied significantly from division to division; some units had been fighting since the Italian campaign, while others had just been organized and deployed in November 1944. The latter was particularly true of the French units, many of which were only recently recruited from the Resistance. Some individual American divisions were still in the formation phase: their infantry regiments had only recently arrived, while artillery and logistics units were still being attached.

| XV. US Corps | VI. US Corps | XXI. US Corps (SHAEF Reserve) |

|

103rd Infantry Division 44th Infantry Division 100th Infantry Division Task Force Harris |

Task Force Hudelson 45th Infantry Division Task Force Herren (70th Infantry Division) Task Force Linden (42nd Infantry Division) 79th Infantry Division |

12th Armored Division 14th Armored Division 36th Infantry Division 2nd French Armored Division (later 1st French Army Corps) |

Objectives

[edit]By 21 December 1944, the German momentum during the Battle of the Bulge had begun to dissipate, evident that the operation was on the brink of failure. It was believe that an attack against the the Vistula-Oder Offensive on the Eastern Front.h ht. extended its lines and taken on a defensive posture to cover the area vacated by the United States Third Army (which turned north to assist at the site of the German breakthrough), could relieve pressure on German forces in the Ardennes.[7] In a briefing at his military command complex at Adlerhorst, Adolf Hitler declared in his speech to his division commanders on 28 December 1944 (three days prior to the launch of Operation Nordwind), "This attack has a very clear objective, namely the destruction of the enemy forces. There is not a matter of prestige involved here. It is a matter of destroying and exterminating the enemy forces wherever we find them."[3]: 499

The goal of the offensive was to break through the lines of the U.S. Seventh Army and French 1st Army in the Upper Vosges Mountains and the Alsatian Plain and destroy them, as well as seize Strasbourg, which Himmler had promised would be captured by 30 January. That would leave the way open for Operation Dentist (Unternehmen Zahnarzt), a planned major thrust into the rear of the U.S. Third Army, intended to lead to the destruction of that army.[3]: 494

Offensive

[edit]On 31 December 1944, German Army Group G (commanded by Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz) and Army Group Upper Rhine (commanded by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler) launched a major offensive against the thinly stretched, 110-kilometre-long (68 mi) front line held by the U.S. 7th Army. Operation Nordwind soon had the overextended U.S. 7th Army in dire straits; the 7th Army (at the orders of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower) had sent troops, equipment, and supplies north to reinforce the American armies in the Ardennes involved in the Battle of the Bulge.

On the same day that the German Army launched Operation Nordwind, the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) committed almost 1,000 aircraft in support. This attempt to cripple the Allied air forces based in northwestern Europe was known as Operation Bodenplatte. It failed without having achieved any of its key objectives.

The initial Nordwind attack was conducted by three corps of the German 1st Army of Army Group G, and by 9 January, the XXXIX (39th) Panzer Corps was heavily engaged as well. By 15 January at least 17 German divisions (including units in the Colmar Pocket) from Army Group G and Army Group Oberrhein, including the 6th SS Mountain, 17th SS Panzergrenadier, 21st Panzer, and 25th Panzergrenadier Divisions were engaged in the fighting. Another smaller attack was made against the French positions south of Strasbourg, but it was finally stopped. The U.S. VI Corps—which bore the brunt of the German attacks—was fighting on three sides by 15 January.

The 125th Regiment of the 21st Panzer Division under Colonel Hans von Luck aimed to sever the American supply line to Strasbourg, by cutting across the eastern foothills of the Vosges at the northwest base of a natural salient in a bend of the River Rhine. Here the Maginot Line, running east–west, was used by Allied forces, and "showed what a superb fortification it was".[8] On January 7 Luck approached the line south of Wissembourg at the villages of Rittershoffen and Hatten. Heavy American fire came from the 79th Infantry Division, the 14th Armoured Division, plus elements of the 42nd Infantry Division. On January 10 Luck reached the villages. Two weeks of heavy fighting followed, Germans and Americans each occupying parts of the villages while civilians sheltered in cellars. Luck later said that the fighting around Rittershoffen had been "one of the hardest and most costly battles that ever raged".[9]

Eisenhower, fearing the outright destruction of the U.S. 7th Army, had rushed already battered divisions hurriedly relieved from the Ardennes, southeast over 100 km (62 mi), to reinforce the 7th Army. But their arrival was delayed, and on 21 January with supplies and ammunition short, Seventh Army ordered the much-depleted 79th Infantry and 14th Armored Divisions to retreat from Rittershoffen and fall back on new positions on the south bank of the Moder River.

On 25 January the German offensive was halted, after the US 222nd Infantry Regiment stopped their advance near Haguenau, earning the Presidential Unit Citation in the process. The same day reinforcements began to arrive from the Ardennes. Although Strasbourg had been successfully defended, the Colmar Pocket had not yet been eliminated.

See also

[edit]Operation Nordwind was the code name of a German military operation in World War II and the last offensive by German forces on the Western Front , during which combat operations took place in Alsace and Lorraine from December 31, 1944 to January 25, 1945 . Although the operation led to political tensions between the United States and France , referred to as the Strasbourg Controversy , it is one of the lesser-known and sometimes even misrepresented [3] major operations of the Second World War ; The public perception is dominated by the simultaneous battles in the Ardennes , in the Hürtgen Forest and on the Eastern Front on the Vistula and Oder .

Temporarily planned as an alternative to the Battle of the Bulge or in support of it, [4] the operation was started long after the attacks there had long since come to a halt. While German troops had already largely cleared the Ardennes and Soviet troops were about to capture Warsaw and were about to achieve their first successes in East Prussia , the fighting in Alsace reached its climax with the deployment of further German divisions. A significant part of the fighting took place from January 8th to 20th, 1945 in the area between Hagenau and Weissenburg , although battles on the Vosges ridge and around a newly formed bridgehead on the Upper Rhine had a much greater influence on the events. The battle ended after the withdrawal of American troops to the Moder line near Hagenau and their success against the last German attacks on January 25th.

Similar to the Ardennes Offensive, the Nordwind offensive was hampered primarily by a lack of fuel, insufficient artillery support and insufficient reconnaissance. Above all, a lack of personnel as well as stubborn Allied resistance are considered to be the decisive reasons for the failure of Nordwind. The units deployed in this section of the front, which had been weakened by the previous retreat, were inadequately staffed, a shortcoming that was only belatedly compensated for by the use of reserves. Operational control was made even more difficult by the fragmented command structure,as the offensive not solely under the purview of Army Group G. The 19th Army was separated from Army Group G and formed the the newly established Army Group Upper Rhine, which was placed under the command of Heinrich Himmler, who had no military experience or staff officer training.

German planning

After the Battle of the Bulge made it necessary to shift larger units of the 3rd US Army north, the staff of the Commander-in-Chief West under General Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt decided to take advantage of the resulting weakening of the enemy in Alsace. Buoyed by the evacuation of the American bridgeheads on the Saar, von Rundstedt ordered the high command of Army Group G on December 21, 1944 to initiate local advances and to make preparations for an attack to recapture the Zaberner Steige .

Three options have been developed for this attack, with advantages and disadvantages listed: [10]

west of the Vosges along the Vosges ridge east of the Vosges + well-developed network of roads and paths

+ Protection of the right flank by the Saar

− high probability of Allied air raids due to the open terrain

− Significant reorganization of forces required

+ Protection through hilly and wooded terrain

+ Maginot Line fortifications still in German hands

− Poorly developed network of roads and paths

− anti-tank terrain

+ well-developed network of roads and paths

− Maginot Line fortifications in American hands

− good defense options in the Holy Forest

− Minefields

After the advance along the Vosges ridge was approved by von Rundstedt and Colonel-General Johannes Blaskowitz (commander-in-chief of Army Group G ), Hitler ordered that the western advance be carried out in support of the main thrust with at least two tank and three infantry divisions. Given the weather conditions in the Vosges (it was a very cold winter), he had doubts about the troops' ability to endure. [11] Von Rundstedt changed his orders to this effect on December 22nd. [12]

Colonel General Johannes Blaskowitz, Commander-in-Chief of Army Group G (1944)

In fact, only this detailed planning had to be carried out, because in October 1944 the Wehrmacht command staff had already developed studies for a counter-offensive in Alsace. Such an offensive was considered on November 17th and 25th as an attack on the flank of the Allied forces that might be pushing across the Rhine and was ultimately rejected in favor of the attack in the Ardennes. Now these studies could be used. [13] The objectives of the operation were determined in a meeting with Blaskowitz on December 24th. The Zaberner Steige between Pfalzburg and Zabern was intended to cut off the lines of communication between the Allied forces in northern Alsace and destroy the latter. The aim was then to establish a connection with the 19th Army by pushing south . For this purpose , two shock groups were formed in the 1st Army area under General of Infantry Hans von Obstfelder . The first - consisting of the XIII. SS Army Corps (two Volksgrenadier - and one SS Panzergrenadier division) - was supposed to break through the Allied lines near Rohrbach east of the Blies and then move towards Pfalzburg together with the second group . The second group – consisting of the LXXXX. Army Corps (two Volksgrenadier divisions) and LXXXIX. Army Corps (three infantry or Volksgrenadier divisions) - should attack from the area east of Bitsch in several thrust wedges and then work together with the first group. Depending on how the situation developed, the offensive should then take place either east or west of the Vosges in the direction of the Pfalzburg-Zabern line.

In order to be able to exploit a breakthrough, the 25th Panzergrenadier Division and the 21st Panzer Division were kept in the army reserve. In the official language of December 25, 1944, the operation was given the code name “Operation Nordwind”. [12]

Sketch of the original operation plan

The southern Army Group Upper Rhine , which was under the supreme command of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, was also included in the planning on December 23, 1944 . She was asked to bind the opposing forces there through shock troops and the formation of bridgeheads across the Rhine north and south of Strasbourg . At times it was also considered to advance with parts of the 19th Army on Molsheim west of Strasbourg, [14] which would also have cut off the Allies' second, smaller line of communication in Lower Alsace. After Hitler scheduled the offensive to begin at 11 p.m. on December 27, 1944, the army group received its final orders. They were only supposed to attack when the units of the 1st Army had taken possession of the eastern exits of the Vosges between Ingweiler and Zabern. Their divisions had the task of breaking through the enemy front north of Strasbourg and uniting with the 1st Army in the Hagenau - Brumath area. The execution of these initially minor operations was the responsibility of the 19th Army under General of Infantry Siegfried Rasp . In addition to smaller battalion-strength advances from the Alsace bridgehead, they primarily planned the attack by the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division near Gambsheim across the Rhine. [15]

After the defeat of the Allied forces in Lower Alsace, the follow-up operation was planned to be Operation Dentist , an advance into the flank of the 3rd US Army . [16]

Intention

Hitler associated “Operation Nordwind” not only with the prospect of further partial success on the Western Front, but also with the idea of getting the deadlocked Ardennes Offensive rolling again. He presented these views in a speech to the commanders and commanders involved on December 28, 1944:

“I completely agree with the measures that have been taken. I hope that we will succeed in moving the right wing [in the Bitsch area] forward quickly in order to open the entrances to Zabern, then immediately push into the Rhine plain and liquidate the American divisions. The destruction of these American divisions must be the goal. […] The mere idea that there would be an offensive again at all had a gratifying effect on the German people. And if this offensive is continued, if the first really great successes appear […] you can be convinced that the German people will make all the sacrifices that are humanly possible. […] I would therefore just like to appeal to you that you support this operation with all your fire, with all your energy and with all your drive. This is a crucial operation. Its success will absolutely automatically entail the success of the second one [in the Ardennes]. […] We will then master fate.”

– Adolf Hitler (December 28, 1944) [17] German forces In addition to the Volkssturm units and local police forces deployed in the bunkers of the West Wall on the Upper Rhine, there were on paper numerous divisions on the German side, some of which were only regimental strong and some were inexperienced.

1st Army Division into two storm groups, [18] XIII. SS Army Corps as Sturmgruppe 1 for the attack west of the Vosges, LXXXX. Army Corps and LXXXIX. Army Corps as Storm Group 2 for the attack on the Vosges ridge.

XIII. SS Army Corps LXXXX. Army Corps LXXXIX. Army Corps other units of the 1st Army 19th Volksgrenadier Division 36th Volksgrenadier Division 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division 559th Volksgrenadier Division 257th Volksgrenadier Division 361st Volksgrenadier Division 245th Infantry Division 256th Volksgrenadier Division 25th Panzer Grenadier Division 21st Panzer Division 6th SS Mountain Division “Nord” (was brought in from Norway immediately after the attack began) 7th Paratrooper Division (was added on January 15th) 11th Panzer Division (deployed in the Orsholz Riegel since January 16th ) 47th Volksgrenadier Division (was added on January 20th) 19th LXIV. Army Corps LXIII. Army Corps XIV SS Army Corps Army Reserve 16th Volksgrenadier Division 189th Infantry Division 198th Infantry Division 708th Volksgrenadier Division 106th Panzer Brigade 159th Infantry Division 259th Infantry Division 338th Infantry Division 716th Infantry Division 553rd Volksgrenadier Division Engineer Battalion No. 405 (was added from January 25th) 10th SS Panzer Division (was added from January 15th) 269th Infantry Division (was moved east from January 15) Allied plans Even as the 3rd US Army was reorganizing to defend against the German Ardennes Offensive, the SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force) became aware of the challenges that faced the 6th US Army Group with its now over-extended section of the front. In a follow-up discussion on December 26, 1944, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had recently been promoted to General of the Army, informed the commander of the 6th US Army Group, Jacob L. Devers , that in order to shorten the front of the 6th US Army Group, he wanted it to be withdrawn from the Upper Rhine to the Vosges ridge. [19] Since neither this statement nor SHAEF's subsequent urging had a formal command character and Devers had doubts about SHAEF's assessment of the situation after the Ardennes fiasco of the Allied military intelligence system, he did not see a withdrawal as urgent. He just let him plan it instead of carrying it out. [20] According to his assessment, which was also shared by the commander of the 7th US Army Alexander Patch , a German attack on the Saar was most likely, [21] especially since the Panzer Lehr Division, which was now deployed in the Ardennes in December carried out a disruptive attack here in 1944. Another possibility, although less likely because of the terrain, was an attack along the Vosges ridge, while a German attack in the Upper Rhine plain was considered absurd because of the sections of the Maginot Line held here by the Americans. [20]

For the reasons mentioned, Patch planned four catch positions that could be used one after the other: [22]

Maginot Line positioning system Bitsch– Niederbronn –Moder Bitsch – Ingweiler – Strasbourg Eastern foothills of the Vosges. Allied forces On paper, the Allies had fewer divisions than the Germans, but they had better personnel and materiel. Levels of experience and training varied significantly from division to division; some units had been fighting since the Italian campaign , while others had just been reorganized and had only been introduced in November 1944. [23] The latter was particularly true of the French associations, many of which were recruited from the Resistance . Individual American divisions were only just in the formation phase; The infantry regiments had already arrived, while the artillery units and logistics were still to be added. [24]

7th US Army XV. US Corps VI. US Corps XXI. US Corps (SHAEF Reserve) 103rd Infantry Division 44th Infantry Division 100th Infantry Division Harris Battle Group Hudelson Battle Group 45th Infantry Division Combat Group Men ( 70th Infantry Division ) Kampfgruppe Linden ( 42nd Infantry Division ) 79th Infantry Division 12th Armored Division 14th Armored Division 36th Infantry Division 2e division blindée (later I French Corps) 1st French Army I. French Corps II French Corps 1st Motorized Infantry Division 3rd Algerian Infantry Division Brigade independent Alsace-Lorraine [25] 1st French Armored Division 2nd Moroccan Infantry Division 4th Moroccan Mountain Division 5th Armored Division 9th Colonial Infantry Division 10th Infantry Division History Attack on the Vosges Ridge, January 1st to 6th

On January 5, 1945, a Jagdtiger from the Heavy Panzerjäger Detachment 653 , which was subordinate to the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division, was shot down by a US tank destroyer near Rimlingen . The hit detonated the tank's ammunition. [26] The offensive, which was only partially reconnaissance by the Allies due to bad weather , [20] began without artillery preparation - as a surprise attack - in the last evening hours of December 31, 1944.

The attack by Sturmgruppe 1 encountered the deeply echeloned defense of the 44th and 100th US Infantry Divisions and, with the exception of a three-kilometer-deep breach, remained in the Bliesbrücken - Rimlingen area . After German attack leaders took Großrederchingen on January 3rd and temporarily broke through to the town of Achen , [27] this attack finally came to a halt on January 5th. [26]

The attack by Sturmgruppe 2 was significantly more successful. The mountainous and wooded area in the Vosges was only held by the 'Task Force Hudelson', which had little to counter the attacking German forces. However, the lack of reconnaissance had a disadvantage on the German side, which left the attacking units disoriented. The 361st Volksgrenadier Division , which had been involved in retreat fighting there a few weeks ago, gained the most space thanks to its knowledge of the terrain. Over the next four days, Storm Group 2 advanced at least 16 kilometers. [28]

The development of the situation prompted Blaskowitz and Obstfelder to take advantage of the initial successes of Sturmgruppe 2 and deploy the 6th SS Mountain Division “North”, which had just arrived from Norway , there. This unit, which clearly had the highest operational value of all German divisions in this section of the front, competed against the 257th and 361st Volksgrenadier Divisions at Wingen and Wimmenau . In the early hours of January 4th, two battalions from this division occupied Wingen and overran an American battalion command post. However, since they had lost communications with their radio truck, they were unable to request reinforcements. American counterattacks initially failed because they were initially aimed at only knocking out a company of Wingen. However, since there was no support attack from the 19th Army /Army Group Upper Rhine, [1] the Americans were able to withdraw forces from sections of the front on the Upper Rhine and launch further counterattacks on Wingen. When the American pressure became overwhelming, the now exhausted German battalions withdrew from Wingen on the night of January 6th to 7th. [29]

Strasbourg The unclear situation regarding Eisenhower 's planned withdrawal behind the Vosges began to spread politically during the attack on Zabern. On the afternoon of January 1st, the SHAEF chief of staff called General Devers and accused the 7th US Army of disobeying orders because it did not move to the Vosges. [30] Devers then stated that preparations were underway, but would take time due to the conditions on site. On the same day, Devers informed Patch that his army would have to move behind the Vosges by January 5th and give up the Upper Rhine plain including Strasbourg. Patch began implementation immediately by taking the units deployed in the course of the Lauter back south. At the same time as the order to Patch, Devers passed this information on to the French government through the French liaison officers. De Gaulle then protested in a letter to Devers. The background to the French attitude was primarily the recent history of Alsace as a bone of contention between Germany and France. Strasbourg in particular, where Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle composed the Marseillaise in 1792, had a status among the French that was only exceeded by the capital Paris. [31] It was also feared that a renewed German occupation would result in reprisals against those sections of the population who had openly shown their loyalty to France after the Allied capture on November 23, 1944. [30] Devers, who shared France's attitude, then sent his chief of staff, Major General Barr, to Eisenhower in Paris on January 2nd to receive clear instructions. De Gaulle also contacted Roosevelt and Churchill and summoned Eisenhower to a meeting in Paris on January 3, where Churchill acted as mediator. [32] De Gaulle described Eisenhower's decision as a national catastrophe, whereas Eisenhower initially stuck to his decision and blamed the French 1st Army for failing to destroy the Alsace bridgehead . [32] De Gaulle then threatened to end French participation in SHAEF, while General Alphonse Juin was also presentThere were hints that France would deny the Allies use of its railway network. In the end, Eisenhower, to Churchill's praise, accepted French concerns. Major General Barr, who was also present, immediately passed the information on to Devers, even before the decision was recorded in writing in the form of a communique on January 7th. [32] Devers thereby stopped the launching movements from the Lauter .

Fighting in the Upper Rhine Plain

Development of the situation in the 19th Army: the solid red line represents the front on December 31, 1944, the red-dotted line on January 12, 1945 After Wingen was evacuated, the OKW gave up the attack in the Vosges or west of it and shifted its focus. The original intention of Army Group G to carry out the attack with armored forces on the eastern edge of the Vosges via the intermediate target of Rothbach west of Hagenau was abandoned due to the development of the situation in the 19th Army's sector of the front described below, in favor of an attack directly eastwards in the Upper Rhine plain from Haguenau. [33]

New bridgehead near Gambsheim, January 5th to 10th While Sturmgruppe 2 was attacking Wingen, the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, which was subordinate to the 19th Army and had the lowest operational value of all the German divisions involved, [34] managed to form one on the night of January 4th to 5th Bridgehead at the confluence of the Zorn and Moder near Gambsheim . Since the American units - here Task Force Linden - could only ensure the defense of this section of the front through scout troops and since the population in this region was friendly to the Germans, [35] the soldiers of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division were able to cross the Rhine unhindered in their assault boats , After securing the bridgehead, expand it to Herlisheim and Offendorf and advance in the southwest to the outskirts of Kilstedt . The supply of the bridgehead was ensured by ferry operations at night, as a bridge would have been exposed to air raids by the Allied Air Force. [33] The Allies assessed the threat from this bridgehead as so low that they made no attempt to seal it off for the next three days [33] , although Patch told the commander of the VI. US Corps had already given the order to destroy the bridgehead on January 6th. [36] It was not until January 8th that he deployed parts of the 12th US Panzer Division to the bridgehead, namely Combat Command B (a maneuver element in brigade strength) against supposedly only 500 to 800 disorganized German infantrymen on the bridgehead. In fact, at this point there were already 3,330 German soldiers - reinforced by anti-tank guns - in well-developed positions. In contrast, the weak infantry component of the 12th US Armored Division reduced the operational value of this unit. Combat Command B arrived at Herlisheim on January 8th. It was possible to penetrate Herlisheim with infantry; However, since the American tanks were kept at bay by the German anti-tank guns and radio communication with the infantrymen was lost, the latter evacuated Herlisheim in the morning hours of January 10th. [37]

Company Solstice, January 8th to 12th The actual support of the 19th Army, codename Operation Sonnenwende , consisted of an attack from January 8, 1945 by the 198th Infantry Division deployed between the Rhine and Ill , parts of the 269th Infantry Division and the 106th Panzer Brigade from the Alsace bridgehead Strasbourg. The section of the front in question had recently been handed over by the Americans to the 1st French Army . The German units managed to throw back all the French forces deployed southeast of the Ill and thus bring the triangle between the Ill and the Rhine back under their control. [37] Three French battle groups of battalion strength were cut off and destroyed by January 13th. [38] Nevertheless, the French forces managed to intercept the German attack on January 12th and bring it to a halt on the Ill in the course of the towns of Benfeld , Erstein and Kraft. The actual goal – the capture of Strasbourg – was not achieved. [37]

Battles for Hatten-Rittershofen, January 8th to 20th

A Panther of the 25th Panzergrenadier Division crossing a tank barrier on the West Wall near Weißenburg, January 6, 1945 In implementation of Eisenhower's withdrawal order, the American forces deployed in the northeastern corner of Alsace had already cleared the area on the Lauter in the first days of January and thus given up Reipertsweiler and Weißenburg. After de Gaulle's intervention, they moved into the first of the planned reception positions on the Maginot Line. Only in the Hatten area on January 8th did the 21st Panzer Division and 25th Panzergrenadier Division, which were pushing out of the Bienwald and merged to form Kampfgruppe Feuchtinger , manage to advance beyond the Maginot Line. [39] At Himmler's urging, the OKW's intention was now to advance via Hatten to Hagenau and to meet in the Bischweiler area with the opposing forces from the Gambsheim bridgehead, according to the VI. to enclose the US Corps in the Sufflenheim area and then destroy it, [40] or at least to tie up the Allied forces here frontally, so that the Sturmgruppe 2 standing on the Vosges ridge and the forces standing in the Gambsheim bridgehead - reinforced by the reserves originally intended for Company Dentist – advance on Hagenau and thus the VI. US Corps could include. [41]

As a result, parts of this town and neighboring Rittershofen repeatedly changed hands in bitter fighting, with neither Americans nor Germans able to gain the upper hand, although the latter received reinforcements from the 7th Paratrooper Division from January 11th to 15th. [42] The civilian population also suffered heavy losses because they were not evacuated by the Americans. Simultaneous attempts to re-enact Sturmgruppe 2's original attack on Zabern failed, [43] although the 6th SS Mountain Division "Nord" succeeded in encircling [44] and destroying an American combat group on January 16th. [45] Meanwhile, the 7th Paratrooper Division managed to fight its way to the Gambsheim bridgehead on the left bank of the Rhine and thus establish a land connection. [46] The 7th Paratrooper Division was withdrawn from the front sector at the end of January.

Stalemate at Herlisheim, January 16th to 21st

Parts of the 12th US Panzer Division on the march from Bischweiler to Drusenheim, January 1945 Since Combat Command B's attempt to push in the Gambsheim bridgehead on January 10th failed, the commander of VI. US Corps deployed the entire 12th US Division there on January 13th, which deployed again on January 16th, Combat Command B again on Herlisheim and Combat Command A on Offendorf and the nearby Steinwald. [47] This time too, Combat Command B managed to penetrate Herlisheim, but the terrain gained was lost again due to a German counterattack. Unnoticed by the Americans, the 10th SS Panzer Division crossed the Upper Rhine in ferries on the night of January 15th to 16th and moved into a command area in the bridgehead . [48] The divisional command post was moved to Offendorf and began planning a breakout from the bridgehead for January 17th. This attack started as planned before dawn and resulted in an indecisive encounter with Combat Command A, which was also attacking (again). [47] It became apparent that in the terrain crisscrossed by towns, the Zorn as well as railway embankments and drainage ditches, the operational value of Tanks were low and they were easily prey to anti-tank guns and rocket-propelled grenades. [49] An attempt by Combat Command B to bypass Herlisheim to the north also failed. On January 18th, the 3./SS-Panzerabteilung 10, which belonged to the 10th SS Panzer Division, managed to destroy a US tank battalion that had invaded Herlisheim, capturing ten Sherman tanks and destroying a US infantry battalion that was also deployed there . [50] On January 19th, another battalion belonging to the 79th US Infantry Division was destroyed near Drusenheim . [51]

The 3rd French Infantry Division bloodily repelled attacks by the 10th SS Panzer Division on Kilstedt from January 17th to 21st . [52]

US retreat behind the fashion, January 20th and 21st

By retreating behind the Moder, the VI. US Corps had a classic tendon position from which it could easily repel the last German attacks Despite the French defensive successes at Kilstedt, there was a risk that the 10th SS Panzer Division would break out of the bridgehead further north, where it had just smashed or wiped out three American battalions. With an advance from the Drusenheim area to the west along the northern Moderufer, they could have unhinged the American front near Hatten and Rittershofen. The danger of a renewed attack by Sturmgruppe 2 as well as the exhausting battle for Hatten and Rittershofen completed a situation picture according to which the front arc of the VI. US Corps slowly became untenable. [53] Although the removal of the German front in the Ardennes freed the 101st US Paratrooper Division and the 28th US Infantry Division and relocated them to Alsace, [54] bad weather conditions delayed the arrival of these reinforcements. Patch managed to obtain Dever's consent for a withdrawal, with which the corps could take up the second holding position on the southern bank of Rotbach, Moder and Zorn in the course of a significantly shortened front line. [55]

The settling movement began on the night of January 20th to 21st and was favored by bad weather; German troops only noticed the retreat after it had already taken place. [56] They pushed forward on January 22nd and expanded the land connection to the Gambsheim bridgehead. [57]

Pushing German forces until January 25th

Minor German soldiers are captured near Schillersdorf in Alsace, January 1945 The withdrawal of Allied forces led to the abandonment of large sections of the Maginot Line . German forces were thus as close to their operational objective Zabern as they were during the fighting for the intermediate objective Wingen. Therefore, the German intention to advance on Zabern remained unchanged. [58] Encouraged by the terrain gained, German forces immediately made a vain attempt to take Hagenau and Bischweiler . [59] On the night of January 24th to 25th, parts of three German divisions appeared in the area between Neuburg and Schweighausen , but were repelled after initial successes. [60] Also on January 25th, attacks by the 6th SS Mountain Division “Nord” on Bischholz and Schillersdorf were repelled. [61] At this point, given the collapse of the German front in the east, continuing the attacks was no longer possible. Hitler therefore ordered the offensive to be stopped. [62] As a result, the 21st Panzer Division and the 25th Panzergrenadier Division were withdrawn on January 27th and relocated to the Eastern Front, [59] the 10th SS Panzer Division followed in February. [52]

Follow After the offensive was completed, German forces again occupied around 40 percent of Alsace. As tactical successes, they were able to record a shortening of the front and lower losses compared to the Allies. However, they were denied strategic success; They failed to destroy any significant Allied forces, nor did they succeed in taking Strasbourg.

By evading the Moder, the Allied forces even gained freedom of action [63] for an attack on the Alsace bridgehead, which led to the destruction of several German divisions in the Vosges and the elimination of this same bridgehead on February 9, 1945. During this period, parts of the former Gambsheim bridgehead were also recaptured, [64] while the area between Moder and the German starting positions was only cleared by German troops during Operation Undertone in March 1945.

Strategically speaking, Operation Nordwind - similar to the stay of German units in the Ardennes - tied up forces that would have been needed much more urgently given the collapse of the Eastern Front ; [65] Nordwind was only canceled at a time when the Red Army had already overrun half of East Prussia ( East Prussian Operation from January 13, 1945) [66] and had enclosed Posen . This development of the situation could no longer be reversed by relocating the divisions previously deployed in Alsace.

All tactical successes could have been achieved at a significantly lower price by clearing the Alsace bridgehead. The bitter fighting could not change the outcome of the war. However, even after the failure of the Battle of the Bulge, they maintained the impression among the Western Allies that the Third Reich had not yet reached the end of its strength.

The Strasbourg controversy was one of the reasons for de Gaulle's partial break with NATO in 1966 and fueled doubts even in the Federal Republic of Germany about American support in the event of a Soviet attack. [67]

Literature

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Cirillo 2003, Retrieved 16 August 2018

- ^ Cirillo 2003, Retrieved 16 August 2018

- ^ a b c Clarke, Jeffrey J.; Smith, Robert Ross (1993). Riviera to the Rhine (CMH Pub 7–10) (PDF). Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Smith, Clark: Riviera To The Rhine. P. 527

- ^ Grandes Unités Françaises, Vol. V-III, p. 801

- ^ Clarke, Jeffrey (1993). U.S. Army in World War II European Theater of Operations: Riviera to the Rhine. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. p. 527.

- ^ Clarke, Jeffrey (1993). U.S. Army in World War II European Theater of Operations: Riviera to the Rhine. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 493–494.

- ^ Ambrose 1997, p. 318.

- ^ Ambrose 1997, p. 386.

Tsingtau in the 1930s

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Tsingtau |

| Namesake | Tsingtau |

| Ordered | 1933 |

| Builder | Blohm & Voss |

| Laid down | 31 October 1933 |

| Launched | 6 June 1934 |

| Commissioned | 24 September 1934 |

| Fate | Scrapped in 1950 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | E-boat tender |

| Tonnage | 2,225 GRT |

| Length | 87.46 m (286 ft 11 in) |

| Beam | 13.5 m (44 ft 3 in) |

| Propulsion | 3,016 kW (4,045 hp) |

| Speed | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h) |

| Complement | 159-251 |

| Armament |

|

The Tsingtau was an S-boat tender ship of the German Reichsmarine and Kriegsmarine that was used in the Second World War.

Design

[edit]The Reichsmarine and Kriegsmarine needed appropriately equipped escort ships for the E-boats that were put into service from 1930 onwards. Special ships were necessary because every flotilla needed an tender ship that could serve as accommodation for the boat crews and as a fuel, ammunition, fresh water and food depot for the boats. Initially, the North Sea, a converted commercial steamer that ran a service to Heligoland, was used for this purpose, but due to its age and low speed it was not an ideal solution and was not built for this purpose. The Reichsmarine therefore ordered the Tsingtau as its first S-boat tender in 1933. She was similar in many ways to the U-boat tender Saar, built around the same time, and was smaller than the S-boat tender Carl Peters and Adolf Lüderitz, built after her.

The ship was commissioned as a fleet tender from Blohm & Voss in Hamburg in 1933 as a replacement for the outdated North Sea, was launched there on June 6, 1934, and was put into service on September 24, 1934. It was 87.46 meters long (waterline 85.00 m) and 13.5 m wide, had a draft of 4.01 m and displaced 1980 tons (standard) or 2490 t (maximum). Two MAN four-stroke diesels with a combined 4,100 hp gave her a top speed of 17.5 knots. The operating range was 8,500 nautical miles at a cruising speed of 15 kn. The ship was armed with two 8.8-cm L/45 guns and four (eight from February 1940) 2-cm anti -aircraft machine cannons. The crew numbered 149 men. As a training ship, the Tsingtau had up to 102 additional men on board.

Service History

[edit]After completing the test trips, the Tsingtau served from November 3, 1934 to February 1940 as an escort ship for the 1st Speedboat Half Flotilla with the first six new S-boats built since 1932. When the boat S 9 was added on June 12, 1935, it was renamed the 1st Speedboat Flotilla. With the commissioning of additional boats, the 2nd Speedboat Flotilla with the escort ship Tanga was set up on August 1, 1938. Both flotillas were commanded by the leader of the torpedo boats (FdT), who in turn reported to the commander of the reconnaissance forces (BdA).

The Tsingtau took part in the attack on Poland in September 1939 with six boats from the 1st Speedboat Flotilla. On January 6, 1940, she was replaced as the escort ship of the 1st Speedboat Flotilla by the new Carl Peters , and from mid-February 1940 she served as an anti-aircraft training ship, now with eight 2 cm anti- aircraft guns .

During the “Weserübung” operation, the Tsingtau brought army troops and soldiers from a naval artillery company to Kristiansand in Norway as an escort ship for the 2nd Speedboat Flotilla and thus as part of “Warship Group 4” to occupy the port there. Afterwards, she and the speedboats initially stayed in Norway to carry out patrol work in the fjords .

At the end of April, the ship returned to Germany with its S-boat flotilla, where it served as a cadet training ship for the inspection of the training system from May to July and then as a target ship for the 1st Torpedo Boat Flotilla until mid-August. On August 21, 1940, the Tsingtau moved to Rotterdam as an escort ship for the speedboats stationed there . From October 1940 she was an escort ship for the 4th Speedboat Flotilla .

In 1941 the Tsingtau was moved to the Baltic Sea, where she served as an escort ship for various flotillas until April 1944 - first the 5th, from February 15, 1942 the 6th, then the 7th, and in June/July 1942 the 8th speedboat -Flotilla . Then from July 1942 to April 1943 she was directly subordinate to the leader of the Schnellboote (FdS). In April 1943 she was assigned to the 9th Speedboat Flotilla , operating in the English Channel .

When the 2nd Speedboat School Flotilla was set up at the Speedboat Training Division in April 1944 , the Tsingtau came to the 2nd Speedboat School Flotilla as an escort ship. It remained there until the end of the war, but was also available to the speedboat leader on several occasions during this time.

Towards the end of the war, numerous missions in the Baltic Sea followed in order to bring as many people as possible from East and West Prussia to the West. On the night of May 5, 1945, the Tsingtau and its speedboats evacuated 3,500 people from the Gotenhafen-Hexengrund torpedo weapons site in the Bay of Danzig . On May 8th, the Tsingtau was part of the very last convoy that once again evacuated soldiers from the Courland Pocket . As she entered the port of Libau , she was shot at by German tanks because no one there believed that German ships would appear for evacuation. On May 8, 1945, around 9:30 p.m., just a few hours before the official end of the war, the last convoy left Libau, with a total of around 15,000 people being brought to the west. Between 2,000 and 3,000 wounded were accommodated on the Tsingtau alone . An order received en route to enter Soviet-occupied Kolberg was ignored and on May 11th or 12th the convoy with the Tsingtau arrived in Kiel.

After the end of the war, the Tsingtau was transferred to the Britain as a war reparation on May 12, 1945. Until 1947 she served under British command with the German Mine Clearance Service, as a tender for the 4th Mine Clearance Division.

In February 1950 the ship was brought to England and scrapped at Clayton & Davie in Dunston on the Tyne (Northumberland) .

References

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Gojny, Jürgen (1950). Das Minenschiff Hansestadt Danzig. Vol. 60. Lübeck: Max Schmidt-Römhold. pp. 151–157. ISSN 0511-8484.

- Rothe, Claus (1989). Bibliothek der Schiffstypen. Vol. 60. Berlin: Verlag für Verkehrswesen. pp. 132–133. ISBN 3-344-00393-3.

- Category:1926 ships

- Category:Ships built in Stettin

- Category:Auxiliary ships of the Kriegsmarine

- Category:Ships sunk by mines

- Category:World War II shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea

- Category:World War II minelayers of Germany

| KH178 105 mm Towed Howitzer | |

|---|---|

| Type | Howitzer |

| Place of origin | South Korea |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1983–present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Agency for Defense Development |

| Designed | 1978–1982 |

| Manufacturer | Kia Machine Tool (1983–1996) Kia Heavy Industry (1996–2001) WIA (2001–2009) Hyundai Wia (2009–present) |

| Produced | 1983–present |

| Variants | KH178MK1 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2,650 kg (5,840 lb) |

| Length | 7.6 m (25 ft) |

| Barrel length | 3.92 m (12 ft 10 in) |

| Width | 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) |

| Height | 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) |

| Crew | 8 (including driver) |

| Caliber | 105 mm (4.1 in) |

| Breech | Horizontal sliding block |

| Recoil | Constant, hydropneumatic |

| Elevation | -5° to 65° (-89 mils to 1,156 mils) |

| Traverse | ±23° (±409 mils) |

| Rate of fire | 15 rds/min maximum 3–5 rds/min sustained |

| Muzzle velocity | 662 m/s (2,170 ft/s) |

| Maximum firing range | 14.7 km (9.1 mi) HE 18 km (11 mi) RAP |

The Type 74 105 mm self-propelled howitzer is only used by Japan. It shares a number of automotive components with the Type 73 armored personnel carrier which was developed during the same time. Komatsu developed the chassis, while the howitzer and turret were designed by Japan Steel Works. The first prototypes were completed in 1969–1970. The howitzer was accepted for service in 1974.

It carries 30 rounds on board. It is amphibious when using the erectable flotation screen stowed around the periphery of the upper hull. It is equipped with an NBC filtration system.

Type 74 was attached to 117th Artillery Battalion in Hokkaido. In 1999, all Type 74s were retired and the battalion was disbanded.[1]

Operators

[edit]

Current operators

[edit] Chile : 16 howitzers in 1991, used by the Chilean Marine Corps.[1][2]

Chile : 16 howitzers in 1991, used by the Chilean Marine Corps.[1][2] Indonesia : 54 howitzers in 2010.[1][3]

Indonesia : 54 howitzers in 2010.[1][3] South Korea : 18 howitzers in 1983, used by the Republic of Korea Army and the Republic of Korea Marine Corps. All retired in 2000.[1]

South Korea : 18 howitzers in 1983, used by the Republic of Korea Army and the Republic of Korea Marine Corps. All retired in 2000.[1]

See also

[edit]

Witzell joined the Imperial German Navy as a midshipman on April 1, 1902, and completed his basic training on the training ship Moltke. He subsequently took part in various foreign voyages with a cruiser squadron and spent several years in the German leased territory of Kiautschou as a company officer and adjutant in the land-based coastal artillery department. After his return home, from April to September 1913, he was initially assigned to the II. Naval Inspectorate. Witzell was then transferred to the Oldenburg as a Kapitänleutnant and artillery officer. In this capacity, he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog and remained on the ship of the line until the start of the First World War, serving there until early September 1915. He was then transferred as an artillery officer to the light cruiser Elbing, with which he participated in the Battle of Jutland on May 31, 1916. For his service, he was awarded both classes of the Iron Cross and the Friedrich August Cross. From June 2 to August 31, 1916, Witzell served as the deputy artillery officer on the light cruiser Frankfurt before being transferred to the Graudenz as navigation officer and first officer, a position he held until the end of the war.

On February 2, 1920, he was assigned to the Wilhelmshaven shore command as an artillery officer and became a member of a sub-commission of the Naval Peace Commission. In this role, he attempted to negotiate with the victorious powers regarding the artillery defense options for the German coast. On June 29, 1920, Witzell was promoted to Korvettenkapitän, and on February 5, 1921, he was appointed head of the weapons department of the naval command. He briefly served as first officer on the ship of the line Braunschweig from January 11 to 31, 1926, and in the same role from February 1, 1926, to September 30, 1927, on the Schleswig-Holstein, where he was promoted to Fregattenkapitän on April 1, 1927. He then returned to his duties as a department head. On October 1, 1928, he was appointed head of the Naval Weapons Department, and on October 1, 1934, he became head of the Naval Weapons Office. During this period, he was promoted to Kapitän zur See on December 1, 1928, and to rear admiral on September 1, 1933. Witzell remained in his post after the creation of the Kriegsmarine, where he played a crucial role in the development and construction of naval weapons.

The Marinewaffenhauptamt oversaw the development, testing and production of naval weapons of all kinds, as well as electronic counter-measures and radio communications. During the interwar period, Witzell, like Chief of the German Navy High Command Erich Raeder, was an advocate of a powerful surface navy that included the heaviest ships. He argued that only the largest vessels could allow an Atlantic striking force to effectively break through and destroy British trade routes. Witzell, Raeder, and many others in the naval staff continued to strongly believe in the importance of capital ships and surface vessels. This perspective ultimately contributed to the development of Plan Z in January 1939.[4]

After the outbreak of the Second World War, he became chief of the Naval Weapons Main Office in the High Command of the Navy on November 7, 1939. Promoted to General Admiral on April 1, 1941, he left active service on August 31, 1942, and was placed at the disposal of the Navy on October 1, 1942, but was no longer called up for active military duty. He was appointed to the Presidential Council of the Reich Research Council and was awarded the Knight's Cross of the War Merit Cross with Swords on October 6, 1942, "in recognition of his great services to weapons development and the armament of the German Reich."

Witzell, along with field marshal Erhard Milch, the Generalluftzeugmeister (Chief of Air Equipment) for the Air Force, and general Emil Leeb, Chief of the Waffenamt (Army Ordnance Office), served on the Armaments Committee (Rüstungsamt). Formed on May 6, 1942, under the leadership of Reich Minister Albert Speer, this committee aimed to centralize the research and development efforts of the three branches of the Armed Forces. By establishing a unified planning agency, the committee sought to streamline ordnance research and optimize resource allocation, ensuring better-coordinated advancements in military technology across the Heer, Luftwaffe, and Kriegsmarine.[5]

Although his military career had ended, Witzell became a Russian prisoner of war in May 1945 and was sentenced to 25 years in prison for war crimes by a military tribunal in the Soviet Union on June 25, 1950. On October 7, 1955, he returned to Friedland with the last German prisoners of war from the Soviet Union ("Homecoming of the Ten Thousand"). He later became a founding member of the Working Group for Military Technology.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

KH178 Userwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chilewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Upgraded KH178 artillery system offers more range - Indo14-Day3 Archived 2017-06-10 at the Wayback Machine - Janes.com, 7 November 2014

- ^ Doherty, Richard (2015). Churchill's Greatest Fear: The Battle of the Atlantic 3 September 1939 to 7 May 1945. Pen and Sword (published Nov 30, 2015). pp. 20–22. ISBN 9781473879416.

- ^ Hentschel, Klaus (1996), "Hermann Göring et al.: Record of a Conference Regarding the Reich Research Council, July 6, 1942", Physics and National Socialism, Basel: Birkhäuser Basel, pp. 304–308, ISBN 978-3-0348-9865-2, retrieved 2024-10-27

External links

[edit]- ^ "KH 178 105 mm Howitzer". Archived from the original on 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2016-10-02.