User:Madd22/Farallon Plate

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

[edit]Lead

[edit].....

The Farallon Plate is also responsible for transporting old island arcs and various fragments of continental crust, which have rifted off of other distant plates. These fragments from elsewhere are called terranes (sometimes, "exotic" terranes). During the subduction of the Farallon Plate, it accreted these island arcs and terranes to the North American Plate. Much of western North America is composed of these accreted terranes.

Article body

[edit]Tomographic imaging of the plate

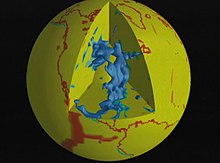

[edit]As an ancient tectonic plate, the Farallon plate must be studied using methods that allow researchers to see deep beneath the Earth's surface. The understanding of the Farallon Plate has evolved as details from seismic tomography provide improved details of the submerged remnants. Since the North American west coast has a convoluted structure, significant work has been required to resolve the complexity.[1]

Seismic tomography can be used to image the remainder of the subducted plate because it is still "cold," as in, it has not reached thermal equilibrium with the mantle. This is important for the use of tomography because seismic waves have different velocities in materials of different temperatures, so the Farallon slab appears as a velocity anomaly on the tomography model.[2][3]

Shallow angle subduction and deformation

[edit]Multiple studies show that the subduction of the Farallon Plate was characterized by a period of "flat-slab subduction," which is the subduction of a plate at a relatively shallow angle to the overriding crust (in this case, North America).[2][4][5][6] This phenomenon is one that accounts for the far-inland orogenisis of the Rocky Mountains and other ranges in North America which are much farther from the convergent plate boundary than is typical of a subduction-generated orogeny.[4][5]

Significant deformation of the slab also occurred due to this flat subduction phenomenon, which has been imaged by seismic tomography. There is a concentration of velocity anomalies in the tomography that is thicker than the slab itself should be, indicating that folding and deformation occurred beneath the surface during subduction.[2][3][6] In other words, more of the slab should be in the lower mantle, but the deformation has caused it to remain shallower, in the upper mantle.[2]

Multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain this shallow subduction angle and resulting deformation. Some studies suggest that the faster movement of the North American Plate caused the slab to flatten, resulting in slab rollback.[2] Another cause of flat slab subduction may be slab buoyancy, a characteristic influenced by the presence of oceanic plateaus (or oceanic flood basalts).[2][7] In addition to influencing slab buoyancy, some oceanic plateaus may have also become accreted to North America.[7][6]

It has been suggested that this deformation may go so far as to include a tear in the slab, where a piece of the subducted Farallon plate has broken off, creating multiple slab remnants. This is supported by tomography studies and provides some more explanation of the formation of Laramide structures that are further inland from the edge.[3][6][8]

Interpretations of Farallon Plate subduction forming the North American Cordillera

[edit]

A 2013 study proposed two additional now-subducted plates that would account for some of the unexplained complexities of the accreted terranes, suggesting that the Farallon should be partitioned into Northern Farallon, Angayucham, Mezcalera and Southern Farallon segments based on recent tomographic models.[1][9] Under this model, the North American continent overrode a series of subduction trenches, and several microcontinents (similar to those in the modern-day Indonesian Archipelago) were added to it. These microcontinents must have had adjacent oceanic plates that are not represented in previous models of Farallon subduction, so this interpretation brings forth a different perspective on the history of collision. Based on this model, the plate moved west, causing the following geologic events to occur:[9]

- 165–155 Myr ago an exotic terrane (the Mezcalera promontory) started to be subducted and the orogenesis of the Rocky Mountains began.

- 125 Myr ago the North American plate collided with a chain of island arcs, causing the Sevier orogeny.

- 124–90 Myr ago the Omineca magmatic belts are formed in the Pacific Northwest as the Mezcalera promontory is overridden.

- 85 Myr ago Sonora volcanism in the Moctezuma volcanic field occurred.

- 85–55 Myr ago the Laramide orogeny occurred as buoyant terranes were accreted.

- 72–69 Myr ago the Carmacks volcanism occured in present-day Canada as an island arc is completely subducted.

- 55–50 Myr ago the accretion of the Siletzia and Pacific Rim terranes occurred.[6]

- 55–50 Myr ago the conclusion of the volcanism of the Coast Mountain island arc occurred.[9]

When the final archipelago, the Siletzia archipelago, lodged as a terrane, the associated trench stepped west. When this happened, the trench that had been characterized as an oceanic-oceanic subduction environment approached the North American margin and eventually became the current Cascadia subduction zone. This created a slab window.[10]

Other models have been proposed for the Farallon's influence on the Laramide orogeny, including the dewatering of the slab which led to intense uplift and magmatism.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Goes 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Schmid, Christian; Goes, Saskia; van der Lee, Suzan; Giardini, Domenico (2002-11-30). "Fate of the Cenozoic Farallon slab from a comparison of kinematic thermal modeling with tomographic images". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 204 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00985-8. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ a b c van der Lee, Suzan; Nolet, Guust (1997-03). "Seismic image of the subducted trailing fragments of the Farallon plate". Nature. 386 (6622): 266–269. doi:10.1038/386266a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Currie, Claire A.; Copeland, Peter (2022-01-25). "Numerical models of Farallon plate subduction: Creating and removing a flat slab". Geosphere. doi:10.1130/GES02393.1. ISSN 1553-040X.

- ^ a b c Humphreys, Eugene; Hessler, Erin; Dueker, Kenneth; Farmer, G. Lang; Erslev, Eric; Atwater, Tanya (2003-07). "How Laramide-Age Hydration of North American Lithosphere by the Farallon Slab Controlled Subsequent Activity in the Western United States". International Geology Review. 45 (7): 575–595. doi:10.2747/0020-6814.45.7.575. ISSN 0020-6814.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Schmandt, B.; Humphreys, E. (2011-02-01). "Seismically imaged relict slab from the 55 Ma Siletzia accretion to the northwest United States". Geology. 39 (2): 175–178. doi:10.1130/G31558.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ a b Kerr, Andrew C. (2015), Harff, Jan; Meschede, Martin; Petersen, Sven; Thiede, Jörn (eds.), "Oceanic Plateaus", Encyclopedia of Marine Geosciences, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 1–15, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6644-0_21-1, ISBN 978-94-007-6644-0, retrieved 2024-10-18

- ^ Hawley, William B.; Allen, Richard M. (2019-07-16). "The Fragmented Death of the Farallon Plate". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (13): 7386–7394. doi:10.1029/2019GL083437. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ a b c Sigloch & Mihalynuk 2013.

- ^ Goes 2013; Sigloch & Mihalynuk 2013.