User:Macrophyseter/sandbox13

| Macrophyseter/sandbox13 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Partial skeleton (MGUAN-PA 065) at the National Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Clade: | †Mosasauria |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Clade: | †Russellosaurina |

| Subfamily: | †Plioplatecarpinae |

| Genus: | †Angolasaurus Antunes, 1964 |

| Species: | †A. bocagei

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Angolasaurus bocagei Antunes, 1964

| |

| Synonyms[3][5][6] | |

| |

Angolasaurus ("Angola lizard") is an extinct genus of mosasaur. Definite remains from this genus have been recovered from the Turonian and Coniacian of Angola,[7] and possibly the Coniacian of the United States, the Turonian of Brazil,[8] and the Maastrichtian of Niger.[9][10] While at one point considered a species of Platecarpus,[6] recent phylogenetic analyses have placed it between the (then) plioplatecarpines Ectenosaurus and Selmasaurus, maintaining a basal position within the plioplatecarpinae.[11]

Its wide geographic range make it the one of the only Turonian mosasaurs with a transatlantic range.[8]

Research history

[edit]

The holotype specimen (SGMA 12/60) was collected from fossil beds just outside Tadi, a town about 1.5 kilometers (0.93 mi) southeast of Iembe, Angola,[6] by M. G. Mascarenhas Neto (then-geologist at the Services of Geology and Mines of Angola) and Portuguese paleontologist Miguel Telles Antunes in 1960.[7] The locality lays within the Late Cretaceous Itombe Formation and was initially dated to the Late Turonian[6] around 90 mya,[12] but later revised to the Early Coniacian around 88 mya.[4] The fossil represents a partial skeleton consisting of a poorly-preserved incomplete and crushed skull, five neck vertebrae, two back vertebrae, and one tail vertebra. It was nevertheless considered as the "most important" and best-preserved African mosasaur fossil at that time by Lingham-Soliar (1994). Antunes initially identified the skeleton as Platecarpus sp. in 1961, but following further study he observed several distinct features in the skull that he believed pertained to a new genus. In 1964, Antunes named this taxon Angolasaurus bocagei.[6] The genus name references the holotype's country of origin while the specific name bocagei honors José Vicente Barbosa du Bocage, a 19th-century Portuguese naturalist who made significant contributions to Angolan herpetology.[13]

Additional fossils that may belong to Angolasaurus have been found outside of Angola. In 1918, Swedish-American geologist Johan August Udden [sv] discovered a skull from Turonian-aged Eagle Ford Shale deposits near Waco, Texas,[5] which was then donated to Lund University in Sweden.[1][5] It was uncritically identified as a 'Mososaurus sp.' [sic] by Adkins (1923).[5] A re-examination of the skull by Polcyn et al. (2007) tentatively reidentified it as an Angolasaurus. The authors also reported a second likely specimen consisting of a partial snout and jaws from another section of the Eagle Ford Shale south of Dallas dated between 91.6-91.41 mya.[1] Bengston and Lindgren (2005) described two isolated teeth from Late Turonian and Turonian-Coniacian layers of the Cotinguiba Formation in the Sergipe Basil of northeastern Brazil. They remarked the teeth to have similar morphology as those in Platecarpus, Plesioplatecarpus, and Angolasaurus (whose monotypic species were all assigned to Platecarpus by the study) but opted to identify then as Platecarpus sp. owning to lack of detailed documentation of Angolasaurus teeth.[14] Polcyn et al. (2007) subsequently affirmed the Brazilian teeth to be indistinguishable from the A. bocagei holotype.[1] Lingham-Soliar (1991) described four isolated vertebrae from the Late Maastrichtian Dukamaje Formation of Niger as comparable with both Angolasaurus and Platecarpus and identified them as cf. ?Angolasaurus.[15] He later referred them as specimens of A. bocagei in 1994.[6] These identifications were doubted as inconsistent with the Turonian-Coniacian specimens due to their far later age by the MS thesis of Woolley (2020),[16] and not recognized in a review by Jiménez-Huidobro et al. (2017).[17]

No more Angolasaurus fossils were recovered from Iembe for the remainder of the 20th century due to Angolan War of Independence and subsequent multi-decade Angolan Civil War. The latter's conclusion in 2002 enabled the formation of an international research team called Projecto PaleoAngola, which began field expeditions into the site in 2005. The group recovered three additional specimens of the mosasaur, including two isolated skulls and another partial skeleton consisting of a complete articulated skull, part of the postcranium, and near-complete forelimbs.[18]

Description

[edit]Angolasaurus was a small mosasaur, with a skull length estimated at 40 centimetres (1.3 ft),[19] suggesting a possible total length of about 4 meters (13 feet) based on the ratio provided by Russell (1967).[20] It shared much of a body plan with its relative Platecarpus, but with a slightly longer skull relative to body length.[6] Its skull housed 11 maxillary teeth, 4 premaxillary teeth, and 12 dentary teeth. The phylogenetic relationship of Angolasaurus indicates that individuals of this genus possessed a tail fluke, more forward-lying nostrils,[21] and keeled scales for hydrodynamic efficiency.[22]

Due to declining sea temperatures in the area that Angolasaurus inhabited, as well as the later Bientiaba locality, it has been hypothesized that it and the other mosasaurs inhabiting its region may have had an increased coverage of dark patterning on its dorsal surface to aid in thermoregulation.[23]

Classification

[edit]Taxonomic placement

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny from Lingham-Soliar (1994), including outdated taxa[a] as written |

Antunes (1964) initially placed Angolasaurus within the Mosasaurinae subfamily on the basis of alleged skull similarities with Clidastes such as in the quadrate and articular bones. Lingham-Soliar (1991) suggested that the former genus should be placed within the Plioplatecarpinae based on broad similarities in vertebrae with Platecarpus. His 1994 study re-examined the Angolasaurus holotype and could not find the Clidastes-like features listed in Antunes (1964), instead finding the associated bones to be most similar to Platecarpus. He presented several additional arguments for a plioplatecarpine identity, the two most powerful being the presence of external exit holes for the basilar artery of the neurocranium (a synapomorphy of advanced plioplatecarpines) and unfused haemal spines in the vertebrae (unique to tylosaurines and plioplatecarpines).

Lingham-Soliar (1994) furthermore reassigned A. bocagei to Platecarpus as a primitive member on the basis that much of the skull is indistinguishable from the latter genus, with remaining differences interpreted as plesiomorphies of it. A phylogenetic analysis by the study found the species to be the most basal member of a Platecarpus paraphyly that also contains Prognathodon, Plioplatecarpus, and Halisaurus inside it; this was not addressed in the justification for A. bocagei's reassignment, however. The second major phylogenetic analysis that examined the species was by Bell and Polycn (2005), which also recovered Angolasaurus as a separate branch within a paraphyletic Platecarpus. The study encoded a different data matrix and sampled more taxa than Lingham-Soliar (1994), so the two phylogenies are not directly comparable. The recovery of well-preserved A. bocagei fossils by Projecto PaleoAngola allowed an updated phylogenetic analysis, which recovered it as falling outside the Platecarpus clade and thus affirmed the validity of Angolasaurus. However, the same publications did not include a formal redescription of A. bocagei. Jiménez-Huidobro et al. (2017) maintained A. bocagei within Platecarpus without discussion, though noted that the species has yet to be properly recharacterized.

Evolutionary history

[edit]

Angolasaurus is among the oldest derived mosasaurs (those with fully aquatic limbs). It generally sits within a basal position of the Plioplatecarpinae in the most recent phylogenies, although its exact placement varies between at the base of the Plioplatecarpini tribe, the Selmasaurini tribe, or as basal to both. Some phylogenetic topologies in Simões et al. (2017) recovered Angolasaurus as ancestral to both the plioplatecarpines and tylosaurines.

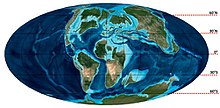

A frontal bone of an indeterminate plioplatecarpine (KUVP 97200) from the Fairport Chalk of Kansas dated slightly older than the Texan Angolasaurus specimens was described by Polcyn et al. (2008) as a morphological intermediate between Yaguarasaurus and Angolasaurus. A phylogenetic analysis by Rivera-Sylva et al. (2023) also recovered Angolasaurus as a descendant of a Yaguarasaurus paraphyly. An alternate phylogeney recovers Yaguarasaurus as instead a member of an independent clade that originated before the divergence of the tylosaurines and plioplatecarpines. Based on such topology, Madzia and Cau (2017) estimated using a Bayesian morphological clock (which approximates divergence times between clades) that Angolasaurus diverged from the rest of the Plioplatecarpinae about 91.49 mya. Jacobs et al. (2009) hypothesized that Angolasaurus originated around the northern Atlantic Ocean and then quickly dispersed southwards into Angola through the recently-opened Gulf of Guinea. The fully aquatic adaptations of the mosasaur, suitable for a open ocean lifestyle, would have enabled it to cross deep-water barriers that had formed in the area by the Late Turonian. Mazuch et al. (2024) speculated that Angolasaurus could have also reached Europe due to its trans-Atlantic distribution, though fossil evidence remains absent.[24]

The following cladogram follows the most recent phylogenetic analysis including Angolasaurus by Longrich et al. (2024), recovering it as basal to both the Plioplatecarpini and Selmasaurini.

| Plioplatecarpinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

[edit]

Angola

[edit]Angolasaurus bocagei, recovered only from the Itombe Formation, shared its habitat with the tylosaurine species Tylosaurus (formerly Mosasaurus) iembeensis and the durophagous shallow-water turtle Angolachelys. Indeterminate halisaurine and plesiosaur remains have also been recovered from this region. Terrestrial fauna consisted solely of the sauropod Angolatitan.[25]

Niger

[edit]Known from the Dukamaje Formation on the basis of a few vertebrae of varying ontogenetic stages, Angolasaurus coexisted here with fellow plioplatecarpine genera Platecarpus and Plioplatecarpus, the globidensine genus Igdamanosaurus, the halisaurine genus Halisaurus, the mosasaurine genus Mosasaurus, and the mosasaurid genus Goronyosaurus.[25]

United States

[edit]Angolasaurus is known from the Eagle Ford Formation of Texas.[citation needed] Other Turonian aquatic reptiles from the Eagle Ford Formation include the plesiosaurs Polyptychodon, Libonectes, Cimoliasaurus, and Plesiosaurus, and the mosasaur Clidastes. Indeterminate mosasaur and plesiosaur remains are also known from here.[26]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Platecarpus ictericus and P. curtirostris are junior synonyms of P. tympanicus. P. somenensis may be Latoplatecarpus nichollsae. Platecarpini is defunct.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Polcyn, M.; Lindgren, J.; Bell Jr., G.L. (2007). Everhart, M.J. (ed.). The possible occurrence of Angolasaurus in the Turonian of North and South America (PDF). Second Mosasaur Meeting. Sternberg Museum, Hays, Kansas. p. 21.

- ^ Ogg, J.G.; Hinnov, L.A. (2012), "Cretaceous", in Gradstein, F. M.; Ogg, J. G.; Schmitz, M. D.; Ogg, G. M. (eds.), The Geologic Time Scale, Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 793–853, doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-59425-9.00027-5, ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9, S2CID 127523816

- ^ a b Jacobs, L.L.; Mateus, O.; Polcyn, M.J.; Schulp, A.S.; Scotese, C.R.; Goswami, A.; Ferguson, K.M.; Robbins, J.A.; Vineyward, D.P.; Buto Neto, A. (2009). "Cretaceous paleogeography, paleoclimatology, and amniote biogeography of the low and mid-latitude South Atlantic Ocean". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 180 (4): 333–341. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.180.4.333.

- ^ a b Mateus, O.; Callapez, P.M.; Polcyn, M.J.; Schulp, A.S.; Gonçalves, A.O.; Jacobs, L.L. (2019). "The Fossil Record of Biodiversity in Angola Through Time: A Paleontological Perspective". In Huntley, Brian J; Russo, Vladimir; Lages, Fernanda; Ferrand, Nuno (eds.). Biodiversity of Angola. pp. 53–76. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-03083-4. ISBN 978-3-030-03082-7. S2CID 67769971.

- ^ a b c d Adkins, W.S. (1924). "Geology and mineral resources of McLennan County". University of Texas Bulletin. 2340: 1–202.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lingham-Soliar, T. (1994). "The mosasaur "Angolasaurus" bocagei (Reptilia: Mosasauridae) from the Turonian of Angola re-interpreted as the earliest member of the genus Platecarpus". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 68 (1–2). doi:10.1007/bf02989445. S2CID 128963124.

- ^ a b Jacobs, L.L.; Mateus, O.; Polcyn, M.J.; Schulp, A.S.; Antunes, M.T.; Morais, M.L; da Silva Tavares, T. (2006). "The occurrence and geological setting of Cretaceous dinosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and turtles from Angola". Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea. 22 (1): 91–100.

- ^ a b Polcyn, M.; Lindgren, J.; Bell, G.L. Jr. (2007). "The possible occurrence of Angolasaurus in the Turonian of North and South America". In Everhart, M.J. (ed.). Abstract Booklet of the Second Mosasaur Meeting (PDF). Hays, Kansas. p. 21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lingham-Soliar, Theagarten (1991). "Mosasaurs from the upper Cretaceous of Niger". Palaeontology. 34: 653–670.

- ^ Moody, R. T. J and Suttcliffe, P. T. C. (1991). The Cretaceous deposits of the Iullemmeden Basin of Niger, central West Africa. Cretaceous Research 12:137-157

- ^ Konishi, Takuya; Caldwell, Michaell (2011). "Two new plioplatecarpine (Squamata, Mosasauridae) genera from the Upper Cretaceous of North America, and a global phylogenetic analysis of plioplatecarpines". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (4): 754–783. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31..754K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.579023. S2CID 85972311.

- ^ Jacobs, L.L.; Polcyn, M.J; Mateus, O..; Schulp, A.S.; Gonçalves, A.O.; Morais, M.L (2016). "Post-Gondwana Africa and the vertebrate history of the Angolan Atlantic Coast". Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 74: 343–362. ISSN 1447-2554.

- ^ Creisler, B. (2000). "Mosasauridae Translation and Pronunciation Guide". Dinosauria On-line. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008.

- ^ Bengston, P.; Lindgren, J. (2005). "First record of the mosasaur Platecarpus Cope, 1869 from South America and its systematic implications". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 8 (1): 5–12. doi:10.4072/rbp.2005.1.01.

- ^ Lingham-Soliar, T. (1991). "Mosasaurs from the upper Cretaceous of Niger" (PDF). Palaeontology. 34 (3): 653–670.

- ^ Woolley, M.R. (2020). Taxonomic and Palaeobiological Assessment of the South African Mosasaurids (MS). University of Cape Town, South Africa.

- ^ Jiménez-Huidobro, P.; Simões, T.R.; Caldwell, M.W. (2017). "Mosasauroids from Gondwanan Continents". Journal of Herpetology. 51 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1670/16-017.

- ^ Mateus, O.; Polcyn, M.J.; Jacobs, L.L.; Araújo, R.; Schulp, A.S.; Marinheiro, J.; Pereira, B.; Vineyard, D. (2012). "Cretaceous amniotes from Angola: dinosaurs, pterosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and turtles". Actas de V Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y su Entorno: 71–105.

- ^ Bardet, Nathalie (2008). "The Cenomanian-Turonian (late Cretaceous) radiation of marine squamates (Reptilia): the role of the Mediterranean Tethys". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 179 (6): 605–623. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.179.6.605.

- ^ Russell, Dale. A. (6 November 1967). "Systematics and Morphology of American Mosasaurs" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History (Yale University): 209–210.

- ^ Lindgren, Johan; Caldwell, Michael W.; Konishi, Takuya; Chiappe, Luis M. (2010-08-09). "Convergent Evolution in Aquatic Tetrapods: Insights from an Exceptional Fossil Mosasaur". PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e11998. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511998L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011998. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2918493. PMID 20711249.

- ^ Lindgren, Johan; Everhart, Michael J.; Caldwell, Michael W. (2011-11-16). "Three-Dimensionally Preserved Integument Reveals Hydrodynamic Adaptations in the Extinct Marine Lizard Ectenosaurus (Reptilia, Mosasauridae)". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e27343. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...627343L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027343. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3217950. PMID 22110629.

- ^ Strganac; et al. (2015). "Stable oxygen isotope chemostratigraphy and paleotemperature regime of mosasaurs at Bentiaba, Angola". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94: 137–143. doi:10.1017/njg.2015.1. S2CID 129659479.[dead link]

- ^ Mazuch, M.; Košťák, M.; Mikuláš, R.; Culka, A.; Kohout, O.; Jagt, J.W.M. (2024). "Bite traces of a large, mosasaur-type(?) vertebrate predator in the lower Turonian ammonite Mammites nodosoides (Schlüter, 1871) from the Czech Republic". Cretaceous Research. 153: 105714. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105714.

- ^ a b "Fossilworks: Angolasaurus". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.