User:LuciaBella3/sandbox

| |

| Lua error in Module:Mapframe at line 384: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'lat_d' (a nil value). | |

| Coordinates: 64° 30' S 60° 30' W | |

| Location | Antarctic Peninsula |

| Geology | Mountain chain |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 50 miles |

Description

[edit]The Nordenskjold Coast (64° 30' S 60° 30' W) is located on the Antarctic Peninsula (also known as Graham Land), a thin, long ice sheet with an Alpine-style mountain chain.[1] The Nordenskjold Coast was discovered by Otto Nordenskjold, a Swedish explorer and geographer, during his Antarctic Exhibition, 1901-1903[2]. The name was suggested by Edwin Swift Balch in 1909, who was part of the Antarctic Exhibition alongside Dr Nordenskjold[3]. The Nordenskjold Coast is owned by Argentina, who managed and ordered the expedition to Antarctica[4].

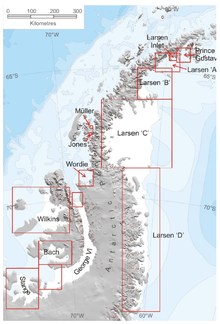

The Nordenskjold coast extends 50 miles west-southwest from Cape Longing to Drygalski Bay and Cape Fareweather, with Oscar II Coast located to the south[5]. The thinness of the Antarctic Peninsula and its northerly location makes it prone to change due to global warming. The length and thickness of ice sheet connected to the Nordenskjold coast is monitored to track the effect climate change has on the coast[6]. The presence of ice shelves that are found on the eastern side of the peninsula have decreased over the past 30 years. The Larsen B ice shelf that was extended from the Nordenskjold Coast disintegrated in 2002[7]. Leaving only a few small ice caps remaining along the coast.

Discovery

[edit]

Otto Nordenskjold left Swedan on the 16th of September[8], 1901, to explore the Antarctic Peninsula and the surrounding islands. They left Sweden on a boat called the Antartic. The Antarctic later sunk leaving the group stranded for a winter on an island off the peninsula[8]. The party spent a month dedicated to sea voyage, along the Antarctic Peninsula, and then settled on an island off the Trinity Peninsula, next to the Nordenskjold Coast at the top of the Peninsula. Due to the harsh weather conditions and the loss of necessary transport, when their boat sunk, the expedition could not explore the coast of the peninsula until spring time in the following September[8].

He discovered new findings about the Antarctic climate to be glacier compared to continental or maritime[9]. The expedition, by exploring the inner parts of the peninsula, found new information about the geological makeup of the Antarctic peninsula explaining how the landform was created[9]. The expedition led to the discovery of fossiliferous rocks deposited during the Cretaceous and Tertiary age. It found that the area was a cordilleran belt of folded strata, this is overlain by sedimentary rocks and volcanic beds from the Mesozoic timer[10]. This discovery, during the 1901 expedition, led to scientists Dalziel and Elliot (1971,1973) able to further amplify the theory of the Pacific crust subduction under the western continental margin.[10]

Geology

[edit]The Nordenskjold coast is located in eastern Graham Land (another name for the Antartic Peninsula). Greywake-shale formations and Metasedimentary sequences, extending to parts of the the Trinity Peninsula located next to the Nordenskjold Coast, makes up the local basement of the Antarctic Peninsula magmatic arc. Metamorphic rocks can be found at the boundary of the Mesozoic – Cenozoic magmatic arc.

The Nordenskjold formation between Cape Longing and Cape Sobral, consists of Upper Jurrasic-Lower Cretaceous anoxic mudstones and air-fall ashes. There’s a possibility of a strike-slip formation based on evidence of deformation, dewatering and lithification. The deformation period was during Tithonian times, and provides further evidence of a plate boundary caused by the break-up of Gondwana along the eastern peninsula. The Nordenskjold formation went through a significant burial period before the Miocene time which brought upon uplifting and block faulting, exposing the area once again[11].

Between Cape Longing and Cape Sobral, the Nordenskjold formation is at its thickest, around 450 cm[12]. Its characterised by ash beds and radiolarian-rich mudstones, around 580m deep. Reports of new calcisphere species, microorganisms that allow scientists to determine time and place in relation to the breakup of Gondwana, found throughout the Nordenskjold formation, have previously been reported in Indonesia and Argentina[13]. This suggests a connection between both regions and provide information about the Gondwana continent.

Geography

[edit]The region has particularly steep slopes on the coast with high covered ice plateau’s. Cape Sobral lies 12 miles from Cape longing, it is a high plank of rock that is projected above the water below, it is partly snow free. Behind Cape Sobral is a deep fiord that is surrounded by glaciers, this fiord extends to Palmier Peninsula[14]. Larsen Bay, which lies between Cape Sobral and Cape Longing, also has a fiord in the middle of its shoreline. Cape Ruth is an area of high peaks that leads to the eastern entrance of Drygalski Bay, the fiord behind Cape Ruth forms the head of Dryglaski Bay.

There is evidence of a plate-boundary on the eastern margin of the peninsula during the breakup of Gondwana. A strike-slip formation found (Whitham and Storey, 1989) proves the possibility of this boundary as well as the spreading of the Weddell Sea Region, and the change from fine anoxic to coarse clastic sedimentation[15].

The Antarctic Peninsula was an active volcanic arc between the Late Jurassic and Tertiary period, created from the south-eastward subduction of the Panthalassa crust, the super ocean that surrounded the supercontinent of Pangea. The finding from Potassium-argon (K-ar) dating from the Schists that line the Nordenskjold coast has found that a metamorphic event, a process of heating and cooling sediments which ultimately changes their composition, happened around the Permian times, estimating its peak at 245-250 Ma.[16]

Climate Change

[edit]Climate

[edit]Along the Antarctic Peninsula over the past 50 years the mean temperature has increased by 3.4 degrees Celsius and the mid winter temperature by 6 degrees[17]. This makes the Antarctic region one of the global hotspots for climate change. The changes in ice shelf mass along the coast of the Peninsula, including the Nordenskjold Coast, has been accelerated by the change in circumpolar currents. The disintegration of the ice sheets do not effect rising sea levels, however, it does contribute to ocean mass as the Larsen a and B ice shelves that fell in 1995 and 2002 were of considerable mass[18].

Permafrost, permanent frozen ground, and the seasonal thaw-activity are two main indicators of climate change. There is a correlation between the mean annual temperatures, − 8 °C and − 1 °C, of the arctic and the boundaries of permafrost on the Antarctic Peninsula[19]. Permafrost can survive if the mean annual temperature remains − 2.5 °C. Due to global warming permafrost levels have become unstable, there is a historic degradation of permafrost levels all over the Antarctic Peninsula, the evidence supports that permafrost levels will continue to be effected by global warming.

Ice Shelves

[edit]

Ice shelves are extended from the Antarctic land masses and are permanent floating ice sheets. They are made from the slow build up of ice, growing into large ice masses. The Antarctic Peninsula has numerous ice shelves called the Larsen Ice shelves[20]. The Larsen B ice shelve is an extension of the Nordenskjold Coast. The flow of grounded ice into the Antarctic ocean is regulated by the ice shelves. Scientists can enhance the processes that control the way atmospheric changes effect the ice shelves. This will allow ocean divers to better estimate the sea level changes.

The major ice shelf in this area, Larsen B ice shelf, disintegrated in 2002 which then triggered an acceleration of the flow from outlet glaciers feeding into the ice shelves, accounting for the continuous loss in mass[7]. There are smaller ice shelves along the Nordenskjold coast have since remained intact. The ice shelves are forming in the four basins along the coast; Dryglaski, Edgeworth, Pyke and Sjögren. All of them are losing mass except for the Pyke Glacier. The ice shelf collapse in 2002 triggered a perturbation of a massive accelerated flow. The instability of the ice shelves mass can be traced back to changes in climate. The Larsen B ice shelf has contributed to 17% of the mass depletion rate of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Please don’t bite me, I’m a newbie!

I’m a university student in a Wikipedia Education class, and I’m currently learning how to contribute to Wikipedia.

I am approaching my subject in good faith.

If you have any concerns or questions, my tutor’s name is Drinion000 (talk · contribs). Thanks!

- ^ "Nordenskjold Coast". Australian Antarctic Data Centre. 22/01/1951. Retrieved 19/03/2020.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hobbs, William H.; Nordenskjold, Otto (1912). "The Swedish South Polar Expedition". Bulletin of the American Geographical Society. 44 (7): 514. doi:10.2307/200883. ISSN 0190-5929.

- ^ Hattersley-Smith, G. (1982-01). "Gazetteer of the Antarctic - Geographic names of the Antarctic, compiled and edited by Fred G. Alberts on behalf of the United States Board on Geographic Names (USBGN). WashingtonNational Science Foundation, 1981, xxii, 959 p. Hardcover US $16.25". Polar Record. 21 (130): 75–76. doi:10.1017/s0032247400004332. ISSN 0032-2474.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sellheim, Nikolas (2016-01-13). "ANTARCTICA IN INTERNATIONAL LAW. Ben Saul and Tim Stephens (editors). 2015. Oxford: Hart Publishing. lxxii + 1062 p, softcover. ISBN 978-1-84946-731-5. £50.00". Polar Record. 52 (5): 613–613. doi:10.1017/s0032247415001035. ISSN 0032-2474.

- ^ Murphy, R. C.; English, Robert A. J. (1944-01). "Sailing Directions for Antarctica, Including the Off-Lying Islands South of Latitude 60 degrees". Geographical Review. 34 (1): 172. doi:10.2307/210611. ISSN 0016-7428.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Davies, Bethan J.; Hambrey, Michael J.; Smellie, John L.; Carrivick, Jonathan L.; Glasser, Neil F. (2012-01). "Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet evolution during the Cenozoic Era". Quaternary Science Reviews. 31: 30–66. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.10.012. ISSN 0277-3791.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Rott, Helmut; Floricioiu, Dana; Wuite, Jan; Scheiblauer, Stefan; Nagler, Thomas; Kern, Michael (2014-11-21). "Mass changes of outlet glaciers along the Nordensjköld Coast, northern Antarctic Peninsula, based on TanDEM-X satellite measurements". Geophysical Research Letters. 41 (22): 8123–8129. doi:10.1002/2014gl061613. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ a b c Nordenskjöld, Otto (1906). "The New Era in South-Polar Exploration". The North American Review. 183 (601): 758–770. ISSN 0029-2397.

- ^ a b Nordenskjold, Otto (1911-09). "Antarctic Nature, Illustrated by a Description of North-West Antarctica". The Geographical Journal. 38 (3): 278. doi:10.2307/1779042. ISSN 0016-7398.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Elliot, David H. (1988), "Tectonic setting and evolution of the James Ross Basin, northern Antarctic Peninsula", Geological Society of America Memoirs, Geological Society of America, pp. 541–556, ISBN 0-8137-1169-X, retrieved 2020-05-18

- ^ Kietzmann, Diego A.; Scasso, Roberto A. (2020-01). "Jurassic to Cretaceous (upper Kimmeridgian–?lower Berriasian) calcispheres from high palaeolatitudes on the Antarctic Peninsula: Local stratigraphic significance and correlations across Southern Gondwana margin and the Tethyan realm". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 537: 109419. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109419. ISSN 0031-0182.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Whitham, A.G.; Storey, B.C. (1989-09). "Late Jurassic—Early Cretaceous strike-slip deformation in the Nordenskjöld Formation of Graham Land". Antarctic Science. 1 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1017/s0954102089000398. ISSN 0954-1020.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kietzmann, Diego A.; Scasso, Roberto A. (2020-01). "Jurassic to Cretaceous (upper Kimmeridgian–?lower Berriasian) calcispheres from high palaeolatitudes on the Antarctic Peninsula: Local stratigraphic significance and correlations across Southern Gondwana margin and the Tethyan realm". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 537: 109419. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109419. ISSN 0031-0182.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Murphy, R. C.; English, Robert A. J. (1944-01). "Sailing Directions for Antarctica, Including the Off-Lying Islands South of Latitude 60 degrees". Geographical Review. 34 (1): 172. doi:10.2307/210611. ISSN 0016-7428.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Whitham, A.G.; Storey, B.C. (1989-09). "Late Jurassic—Early Cretaceous strike-slip deformation in the Nordenskjöld Formation of Graham Land". Antarctic Science. 1 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1017/s0954102089000398. ISSN 0954-1020.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Smellie, J.L.; Millar, I.L. (1995-06). "New K-Ar isotopic ages of schists from Nordenskjöld Coast, Antarctic Peninsula: oldest part of the Trinity Peninsula Group?". Antarctic Science. 7 (2): 191–196. doi:10.1017/s0954102095000253. ISSN 0954-1020.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bockheim, J.; Vieira, G.; Ramos, M.; López-Martínez, J.; Serrano, E.; Guglielmin, M.; Wilhelm, K.; Nieuwendam, A. (2013-01). "Climate warming and permafrost dynamics in the Antarctic Peninsula region". Global and Planetary Change. 100: 215–223. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.10.018. ISSN 0921-8181.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Berthier, Etienne; Scambos, Ted A.; Shuman, Christopher A. (2012-07). "Mass loss of Larsen B tributary glaciers (Antarctic Peninsula) unabated since 2002". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (13): n/a–n/a. doi:10.1029/2012gl051755. ISSN 0094-8276.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bockheim, J.; Vieira, G.; Ramos, M.; López-Martínez, J.; Serrano, E.; Guglielmin, M.; Wilhelm, K.; Nieuwendam, A. (2013-01). "Climate warming and permafrost dynamics in the Antarctic Peninsula region". Global and Planetary Change. 100: 215–223. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.10.018. ISSN 0921-8181.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Griggs, J. A.; Bamber, J. L. (2009-10-03). "Ice shelf thickness over Larsen C, Antarctica, derived from satellite altimetry". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (19): L19501. doi:10.1029/2009GL039527. ISSN 0094-8276.