User:Lucas.o.strom/articledraft

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Old Testament theology is the branch of Biblical Theology that deals with the history, progress, and Christian interpretation of divine revelation in the Old Testament. The events, teachings, and laws in the Old Testament formed the basis of Judaism, and also deeply informed early Christianity. The first Christians were in fact a sect of Jews who followed the teachings of Christ, who was himself a rabbi in the Jewish tradition. When Christianity grew distinct from Judaism, some Old Testament teachings were abandoned or replaced by teachings of Christ, according to the concept of Supersessionism. The Mosaic Covenant comprises the bulk of what is replaced, according to Christians, by the New Covenant.

Themes

[edit]Divine Revelation

[edit]The Judeo-Christian God reveals himself to the Israelites through the course of the Old Testament. According to the Book of Genesis, humankind itself is a creation of God himself, and retains his personal interest. Through communications with characters such as Abraham, Moses, Job, and many of the prophets, God reveals his interest in the people of Israel, and the lives he expects them to live.

History of Israel

[edit]

The Old Testament chronicles the history of the people and nation of Israel throughout the books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemia, and Esther.

The Old Testament traces Israel back to the patriarch Jacob, grandson of Abraham. The stories in Genesis 32 and Hosea 12 tell of Jacob fighting with and overcoming an angel of God. This prompts the angel to rename him Israel, meaning "one who has prevailed with God." Jacob's offspring (primarily his sons) go on to become the twelve tribes of Israel. Following a famine, Jacob leads the people of Israel into Egypt, where they are enslaved. Several generations later, Moses leads the Israelites out of bondage and into the desert, where he hear's God's commandments. During this time the Israelites struggle with their faith.

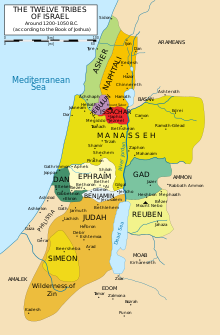

After the death of Moses, the patriarch Joshua leads the Israelites to conquer the land of Canaan. The twelve tribes unite to form the Kingdom of Israel, which finds itself threatened by its neighbors. This period of settlement is detailed in the Book of Judges, describing each Judge's cyclical struggle against oppressive rival leaders. The Judges also struggle with the problem of Israelites failing to worship their God, which is in fact the source of their problems; according to Jewish and Christian theology, it is the unfaithfulness of the Israelites which causes them to be delivered to their enemies.[1]

Eventually the Judges are replaced by a series of kings, the most important of whom is David. After the death of David's son Solomon, the kingdom is split in two: the Northern Kingdom of Israel and the Southern Kingdom of Judah. The Northern Kingdom remains unstable, with a number of dynastic changes, until being conquered by the Assyrian Empire. Judah lasts a couple of centuries longer, continuing the line of David, until it was conquered by the Babylonian Empire. Following this the Judeans are exiled to Babylon. After about 50 years, Babylon becomes controlled by the Persian Cyrus the Great. Over the next 30 years, Jews (as they had begun to be known, the old tribes being long gone) return to Judah and build the Second Temple in Jerusalem on the same site as the First Temple.[2]

Problem of Evil

[edit]The problem of evil is encountered throughout the Old Testament, and is one of the first conflicts to appear in Genesis. Augustinian theodicy claims that Adam and Eve's disobedience to God's prohibition against eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, followed by the Fall of Man, was the source of evil and suffering in the world. This position holds that God is not responsible for the introduction of evil, because it was brought about by humans' use of free will. St. Augustine argued that God created a perfect world, and defined evil as a privation of good, such that evil was not in fact something God created. [3]

After Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden, they bear a number of children, and the people come to be wretched and sinful in God's eyes. God decides to destroy evil by flooding the earth (see flood myth), saving only Noah and his family. Although Noah was viewed by God as righteous and "perfect in his generation,"[4] evil and sin persisted in the world, and God was not satisfied. For a more isolated example, in Genesis God destroys the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah because of the sins of their inhabitants. The Pentateuch contains similar examples of God using his power against localized instances of sin and evil. The theological interpretation of these events is that God's actions are inherently just, because the lives ended by the flood, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and other instances of divine violence were wicked and sinful. They are considered responsible for their suffering.[5].

The Book of Job is especially important to the Christian interpretation of the problem of evil. The story questions the concept of unjust suffering, and the characters take different sides. In Book 21, a miserable Job goes so far as to claim that there is no moral order in the universe. God rebukes Job and his friends, answering that as Creator he alone understands the way the universe works, and that they have no authority on which to accuse God of being unjust. Theologians have debated the conclusions and message of the Book of Job; some have interpreted Job as an ungrateful servant of the Lord, others as a patient mortal tested to his limit.[6]

God's Covenant with His People

[edit]Throughout the Old Testament, God develops a series of covenants with people, tribes, and nations. They generally involve a pledge of protection by God in exchange for worship and following his laws. The collection of agreements, especially the one with Moses, came to be known as the Old Covenant (as opposed to the New Covenant brought about by the resurrection of Jesus Christ).

The first covenant comes at the end of the Great Flood in Genesis 8. In it, God blesses Noah and his family (who are, implicitly, the entirety of humankind[7]), commands them to "be fruitful and multiply," reaffirms humankind's dominion over plants and animals, forbids murder, and promises not to repeat the Flood.[8] Christian theology associates the Flood with the waters of baptism, in that they were both intended to cleanse sin. But whereas the Flood was a forceful judgement by God upon the world, doctrine holds that people baptized as Christians do so as an acknowledgement of their original sin, and their wish to be saved from it through faith and devotion to God.[9]

In the covenant with Abraham, found in Genesis 12–17, God promises to make a great nation of Abraham, his descendants being God's chosen people. He offers a great expanse of land, kings for sons, and his favor. In return, God demands the institution of circumcision.[10] The importance of this covenant is that it is meant to be timeless, and continue to be honored by Abraham's descendants. It is also meant to be collective, that is, members were to be excluded if they did not honor the covenant. Von Rad notes that later in the Old Testament, circumcision was an identifier of the Israelites (and a "question of their witness to Yahweh") during their exile in Babylon, where it was not practiced by the local peoples.[11]

In the covenant with Moses, found in Exodus 19–24, God designates Israel as his chosen people, and gives them Sabbath. In return, God demands that the people of Israel follow his laws, some of which are given to Moses in the form of the Ten Commandments. The Book of Deuteronomy, the final book of the Pentateuch, contains further details of the Mosaic Covenant. Deuteronomy 12–26 outlines the Deuteronomic Code, with prescribed rules for diet, slavery, ceremonies, charity, rape, and more. The formal law given to Israel signals a transition from a nomadic existence to an agrarian one,[12] and presages the development of the nation of Israel.

The covenant with Israel is outlined in Deuteronomy, Jeremiah, Zechariah, 1 Kings, Hosea, and Ezekiel. In this covenant God predicts a number of political changes and conflicts for the people of Israel. After warning that Israel will be dispersed among the nations, and conditional to Israel's repentance, return to God, and obedience to the Mosaic law.

In the covenant with David, God crowns David as the one true king of Israel, and proclaims that the kingdom will not depart from his line. He promises David a son who will build up the temple. Like the covenant with Abraham, this covenant is meant to be timeless and permanent. The passage 2_Samuel 7:12–16 is viewed in Christian theology as being ultimately fulfilled by the Messiah Jesus, who was born in Bethlehem, the town of David's origin.

Prophecy

[edit]There are a number of statements made in the Old Testament which Christian theology interprets as messianic prophecies, which they believe to have been fulfilled by the life and death of Christ in the New Testament. Some notable prophecies include:

- Jeremiah 23:5–6, which is interpreted to predict the messiah's Davidic ancestry;

- Isaiah 7:14, which claims that the Son of God will be born of a virgin;

- Ecclesiastes 12:11, which likens the messiah to a shepherd, as in Ezekiel and elsewhere;

- Isaiah 53:5–11, which claims the messiah will be put to death as a sacrifice;

- Psalms 22, which is interpreted to predict the suffering of the Crucifixion (especially the line "They have pierced my hands and my feet")[13];

- Psalms 16:9–11, which is interpreted to predict the Resurrection;

Christian theology associates numerous other passages in the Old testament with events and writings found in the New Testament. Old Testament messianic prophecies vary widely in specificity, and some were satisfied within the story they came from, to be reapplied to Christ in the New Testament.[14]

See Also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Soggin, J. Alberto (1981). Judges: a Commentary. Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 4. 0664223214.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: an Introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist. pp. 18–20. 0809136104. }}

- ^ "The Theodicy of Augustine of Hippo". Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Genesis 6:7–9

- ^ Crenshaw, James L. (2005). Defending God: Biblical Responses to the Problem of Evil. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 174-176 id = 0195140028.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|page=(help) - ^ Barton, John (2001). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 353-354 id = 0198755007.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|page=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Barton, John (2001). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 46. 0198755007.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Genesis 8–9

- ^ Barton, John (2001). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 129-130. 0198755007.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Genesis 17:9–14

- ^ Von Rad, Gerhard (1973). Genesis: A Commentary. Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 199-201 id = 0664227457.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|page=(help) - ^ Brueggemann, Walter (2005). Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. p. 187. 0800637658.

- ^ Jackson, Wayne. "Psalm 22: a Brief Analysis". Christian Courier. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Robert L. (Spring 2002). "The New Testament Use of the Old Testament" (PDF). The Master's Seminary Journal. 13 (1). Sun Valley, CA: 79–98. Retrieved 5 December 2011.