User:LazyStarryNights/Habanera (music)

TODO

[edit]Dedouble references

Replace this ny somethin else wikidata? [[es:Contradanza]]

the French contra dance or [contradanza]]??

Make separate rhythm article?

Check

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special%3AWhatLinksHere&limit=100&target=Habanera+%28music%29&namespace=0 Maybe also portals And contra

Used with inconsistency

The precursor of the danzón is the Habanera, which is a creolized Cuban dance form.

...

The English contradanza was the predecessor of the ("habanera") also known as danza criolla, of this Creole genre Habanera born in 1879 another Cuban genre, called danzon, were sequence dances, in which all danced together a set of figures.[1]

Used to refer to the rhythm:

Blues Handy was a formally trained musician, composer and arranger who helped to popularize the blues by transcribing and orchestrating blues in an almost symphonic style, with bands and singers. He became a popular and prolific composer, and billed himself as the "Father of the Blues"; however, his compositions can be described as a fusion of blues with ragtime and jazz, a merger facilitated using the Cuban habanera rhythm that had long been a part of ragtime;[2][3] Handy's signature work was the "Saint Louis Blues".

Catalonia (links) Musically, the Havaneres are also characteristic in some marine localities of the Costa Brava especially during the summer months when these songs are sung outdoors accompanied by a cremat of burned rum.

Jazz

Many references to rhythm and music. Seek to align and reuse.

Mambo (music) Modern mambo began with a song called "Mambo" written in 1938 by brothers Orestes and Cachao López. The song was a danzón, a dance form descended from European social dances like the English country dance, French contredanse, and Spanish contradanza. It was backed by rhythms derived from African folk music. ... Contradanza arrived in Cuba in the 18th century, where it became known as danza and grew very popular. The arrival of black Haitians later that century changed the face of contradanza, adding a syncopation called cinquillo (which is also found in another contradanza-derivative, Argentine tango).

By the end of the 19th century, contradanza had grown lively and energetic, unlike its European counterpart, and was then known as danzón. The 1877 song "Las alturas de Simpson" was one of many tunes that created a wave of popularity for danzón. One part of the danzón was a coda which became improvised over time. The bands then were brass (orquestra tipica), but was followed by smaller groups called charangas.

African American music began incorporating Afro-Cuban rhythmic motifs in the 1800s with the popularity of the Cuban contradanza (known outside of Cuba as the habanera).[4] The habanera rhythm can be thought of as a combination of tresillo and the backbeat.

For the more than quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the Cuban genre habanera was a consistent part of African American popular music.[5] Jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton considered the tresillo/habanera rhythm (which he called the Spanish tinge) to be an essential ingredient of jazz.[6] ...

In his composition "Misery," New Orleans pianist Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd) plays a habanera-like figure in his left hand. The deft use of triplets is a characteristic of Longhair's style.

Morton is also notable for naming and popularizing the "Spanish tinge" (habanera rhythm and tresillo)

Not significant

| Music of Cuba | ||||

| General topics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related articles | ||||

| Genres | ||||

|

||||

| Specific forms | ||||

|

||||

| Media and performance | ||||

|

||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||

|

||||

| Regional music | ||||

|

||||

xxxmixxxx

[edit]The habanera is the name used outside of Cuba for the Cuban contradanza (also called contradanza criolla, danza, or danza criolla), a genre of popular dance music of the 19th century.[7] It is a creolized form which developed from the French contra dance. It has a characteristic "habanera rhythm", and is performed with sung lyrics. It was the first written music to be rhythmically based on an African motif, and the first Cuban dance to gain international popularity.

In Cuba itself, the term "habanera" . . . was only adopted subsequent to its international popularization, coming in the latter 1800s—Manuel (2009: 97).[8]

Carpentier states that the Cuban contradanza was never called the habanera by the people who created it.[9] The first documented Cuban contradanza, and the first known piece of written music to feature the habanera rhythm was "San pascual bailón" (1803).[10]

Rhythm

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

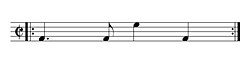

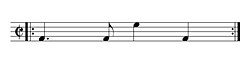

[edit]The habanera rhythm is an embellishment of tresillo, and one of the most basic rhythmic cells in Afro-Latin music, and sub-Saharan African music traditions. In sub-Saharan rhythmic structure, every triple-pulse pattern has its duple-pulse correlative; the two pulse structures are two sides of the same coin. The habanera rhythm is the duple-pulse correlative of the most basic triple-pulse cell—the three-against-two cross-rhythm (3:2), or vertical hemiola.[12]

The habanera rhythm is known by several names, such as the congo,[13] tango-congo,[14] and tango.[15] Thompson identifies the rhythm as the Kongo mbilu a kakinu, or 'call to the dance.'[16][17] The pattern is in fact, heard throughout Africa, and in many Diaspora musics.[18] It is constructed from multiples of a basic durational unit, and grouped unequally so that the accents fall irregularly in a one or two bar pattern.[19] Put another way, the pattern is generated through cross-rhythm.[20]

Some vocalizations of the habanera include "boom...ba-bop-bop",[16] and "da, ka ka kan."[17] When sounded with the Ghanaian beaded gourd instrument axatse, the pattern is vocalized as: "pa ti pa pa." The "pa's" sound tresillo by striking the gourd against the knee, and the "ti" sounds main beat two by raising the gourd in an upward motion and striking it with the free hand.[21] As is common with many African rhythms, the axatse part begins (first "pa") on the second stroke of the habanera (one-ah), and the last "pa" coincides with beat one. By ending on the beginning of the cycle, the axatse part contributes to the cyclic nature of the overall rhythm.

xxxcontraxxx

[edit]Cinquillo, tresillo, and the habanera rhythm

[edit]

The cinquillo (a variant of the more basic tresillo) is a syncopated rhythmic cell whose introduction into the contradanza/danza began its differentiation from a strictly European form of music. Carpentier (2001:149) states that the cinquillo was brought to Cuba in the songs of the black slaves and freedmen who emigrated to Santiago de Cuba from Haiti in the 1790s. Although the cinquillo was introduced into the contradanza in Santiago at the beginning of the 19th century, composers in western Cuba remained ignorant of its existence:

"In the days when a trip from Havana to Santiago was a fifteen-day adventure (or more), it was possible for two types of contradanza to coexist: one closer to the classical pattern, marked by the spirits of the minuet, which later would be reflected in the danzón, by way of the danza; the other, more popular, which followed its evolution begun in Haiti, thanks to the presence of the 'French Blacks' in eastern Cuba (Carpentier 2001:150)."

Manuel disputes Carpentier's claim that the cinquillo was first incorporated into the contradanza in Santiago. Among other things, Manuel cites "at least a half a dozen Havana counterparts, whose existence refutes Carpentier's claim for the absence of the cinquillo in Havana contradanza" (Manuel 2009: 55-56).[26] The cinquillo pattern is sounded on a bell in the folkloric Congolese-based makuta, as played in Havana.[27] As one of the most common rhythmic patterns found in Africa and in music of the Diaspora, cinquillo survived in many former slave ports of the New World, including both Santiago and Havana.

Tresillo is used for ostinato bass figures of some contradanzas, such as "Tu madre es conga."[28] Another tresillo variant popularized by the Cuban contradanza is the rhythmic cell referred to as the habanera rhythm,[29] congo,[30] tango-congo,[31] or tango.[32]

History

[edit]Cuba

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

[edit]In the mid-19th century, the habanera developed from the French contradanza,[33] which had arrived in Cuba (from France via Haiti) with refugees from the Haitian revolution in 1791.

xxxcontraxxx

[edit]Origins and Early Development PART 1

[edit]Its origins dated back to the European contredanse, which was an internationally popular form of music and dance of the late 18th century. It was brought to Santiago de Cuba by French colonists fleeing the Haitian Revolution in the 1790s (Carpentier 2001:146).

The earliest Cuban contradanza of which a record remains is "San Pascual Bailón," written in 1803 (Orovio 1981:118). This work shows the contradanza in its embryonic form, lacking characteristics that would later set it apart from the contredanse. The time signature is 2/4 with two sections of eight bars, repeated- AABB (Santos 1982).

xxxhabaxxx

[edit]The earliest identified "contradanza habanera" is La Pimienta, an anonymous song published in an 1836 collection. The main innovation from the French contradanza was rhythmic, as the habanera incorporated the tresillo into its structure.[34]

Another novelty was that, unlike the older contradanza, the habanera was sung as well as danced.[35] The habanera is also slower and, as a dance, more graceful in style than the older contradanza. The music, written in 2/4 time, features an introduction followed by two parts of 8 to 16 bars each.[36] The upbeat on two-and [or one-ah in 2/4] in the middle of the bar is the power of the habanera rhythm, especially when it is in the bass.[16] The earliest known piece to use the habanera rhythm in the left hand of the piano was "La pimienta," written in 1836.[37]

In Cuba, the habanera was supplanted by the danzón from the 1870s onwards. Musically, the danzón has a different but related rhythm, the baqueteo, and as a dance it is quite different. Also, the danzón was not sung for over forty years after its invention. In the twentieth century the habanera gradually became a relic form in Cuba, especially after success of the danzón and later the son. However, some of its compositions were transcribed and reappeared in other formats later on. Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes' habanera Tú is still a much-loved composition, showing that the charm of the habanera is not dead yet.[38]

In 1995 a modern Cuban artist recorded a complete disc in the habanera genre, when singer/songwriter Liuba Maria Hevia recorded some songs researched by musicologist Maria Teresa Linares. The artist, unhappy with the technical conditions at the time (Cuba was in the middle of the so-called Periodo Especial), re-recorded most of the songs on the 2005 CD Angel y su habanera. The original CD Habaneras en el tiempo (1995) sold poorly in Cuba, which underlines the fading interest in this kind of music there, contrasting with the vigorous popularity of the habanera in the Mediterranean coast of Spain.

Spain and other countries

[edit]It is thought that the habanera was brought back to Spain by sailors, where it became popular for a while before the turn of the twentieth century. The Basque composer Sebastian Yradier was known for his habanera La Paloma (The dove), which achieved great fame in Spain and America.

The habanera was danced by all classes of society, and had its moment of glory in English and French salons. It was so well established as a Spanish dance that Jules Massenet included one in the ballet music to his opera Le Cid (1885), to lend atmospheric color. The Habanera from Bizet's Carmen (1875) is a definitive example, though the piece is directly derived from one of Yradier's compositions (the habanera El Arreglito). Maurice Ravel wrote a Vocalise-Étude en forme de Habanera, as well as a habanera for Rapsodie espagnole (movement III, originally a piano piece written in 1895), Camille Saint-Saëns' Havanaise for violin and orchestra is still played and recorded today, as is Emmanuel Chabrier's Habanera for orchestra (originally for piano). Bernard Herrmann's score for Vertigo (1958) makes prominent use of the habanera rhythm as a clue to the film's mystery.

In the south of Spain: Andalusia (especially Cadiz), Valencia, and Alicante, and in Catalonia, the habanera is still popular, especially in the ports. The habaneras La Paloma, La bella Lola or El meu avi (My grandfather) are well known.[39] From Spain, the habanera arrived in the Philippines, where it still exists as a minor art-form.[40]

The Argentine milonga and tango makes use of the habanera rhythm of a dotted quarter note followed by three eighth notes, with an accent on the first and third notes.[41]

In 1883 Ventura Lynch, a student of the dances and folklore of Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, noted the popularity of the milonga: "The milonga is so universal in the environs of the city that it is an obligatory piece at all the lower-class dances (bailecitos de medio pelo), and it is now heard on guitars, on paper-combs, and from the itinerant musicians with their flutes, harps and violins. It has also been taken up by the organ-grinders, who have arranged it so as to sound like the habanera dance. It is danced in the low life clubs around...[main] markets, and also at the dances and wakes of cart-drivers, soldiery, compadres and compadritos''.[42]

To some extent, the habanera rhythm is retained in early tangos, notably El Choclo[41] and including "La morocha" (1904).[43] As the consistent rhythmic foundation of the bass line in Argentine Tango, the habanera lasted for a relatively short time. Gradually the variation noted by Roberts (see above) began to predominate.[44]p124 Ornamented and distributed throughout the texture, it remains an essential part of the music.[44]p2 Anibal Troilo's "La trampera" (Cheating Woman), written in 1962, uses the same habanera seen in Bizet's Carmen.[17][45]

African American music

[edit]

African American music began incorporating Cuban musical motifs in the 1800s with the popularity of the habanera. Musicians from Havana and New Orleans would take the twice-daily ferry between both cities to perform and not surprisingly, the habanera quickly took root in the musically fertile Crescent City. Whether the habanera rhythm and variants such as tresillo were directly transplanted from Cuba, or if the habanera merely reinforced habanera-like "rhythmic tendencies" already present in New Orleans music is probably impossible to determine. There are examples of habanera-like rhythms in a few African American folk musics such as the foot stomping patterns in ring shout and the post-Civil War drum and fife music.[46] The habanera rhythm is also heard prominently in New Orleans second line music.

The habanera rhythm can be thought of as a combination of tresillo and the backbeat.

John Storm Roberts states that the musical genre habanera, "reached the U.S. 20 years before the first rag was published."[47] Scott Joplin's "Solace" (1909) is considered a habanera (though it's labeled a "Mexican serenade").

For the more than quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime, and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the habanera was a consistent part of African American popular music.[48] Early New Orleans jazz bands had habaneras in their repertoire and the tresillo/habanera figure was a rhythmic staple of jazz at the turn of the 20th century. "St. Louis Blues" (1914) by W.C. Handy has a habanera/tresillo bass line. Handy noted a reaction to the habanera rhythm included in Will H. Tyler's "Maori": "I observed that there was a sudden, proud and graceful reaction to the rhythm...White dancers, as I had observed them, took the number in stride. I began to suspect that there was something Negroid in that beat." After noting a similar reaction to the same rhythm in "La Paloma", Handy included this rhythm in his "St. Louis Blues," the instrumental copy of "Memphis Blues," the chorus of "Beale Street Blues," and other compositions."[49]

Jelly Roll Morton considered the tresillo/habanera (which he called the Spanish tinge) to be an essential ingredient of jazz.[50] The habanera rhythm can be heard in his left hand on songs like "The Crave" (1910, recorded 1938).

Now in one of my earliest tunes, “New Orleans Blues,” you can notice the Spanish tinge. In fact, if you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz—Morton (1938: Library of Congress Recording).[51]

Although the exact origins of jazz syncopation may never be known, there’s evidence that the habanera/tresillo was there at its conception. Buddy Bolden, the first known jazz musician, is credited with creating the big four, a habanera-based pattern. The big four (below) was the first syncopated bass drum pattern to deviate from the standard on-the-beat march.[52] As the example below shows, the second half of the big four pattern is the habanera rhythm.

A habanera was written and published in Butte, Montanta in 1908. The song was titled "Solita" and was written by Jack Hangauer.[54]

xxxcontraxxx

[edit]Origins and Early Development PART 2

[edit]During the first half of the 19th century, the contradanza dominated the Cuban musical scene to such an extent that nearly all Cuban composers of the time, whether composing for the concert hall or the dance hall, tried their hands at the contradanza (Alén 1994:82). Among them, Manuel Saumell (1817–1870) is the most noted (Carpentier 2001:185-193).

The contradanza, when played as dance music, was performed by the orquesta típica, an ensemble composed of two violins, two clarinets, a contrabass, a cornet, a trombone, an ophicleide, paila and a güiro (Alén 1994:82).

Danza

[edit]xxxcontraxxx

[edit]According to Argeliers Léon (1974:8), the word danza was merely a contraction of contradanza and there are no substantial differences between the music of the contradanza and the danza. In fact, both terms continued to denominate what was essentially the same thing throughout the 19th century.[55]

A danza entitled " El Sungambelo," dated 1813, has the same structure as the contradanza- the four-section scheme is repeated twice: ABAB (Santos 1982). In this early piece, the cinquillo rhythm can already be heard.

Later Development

[edit]xxxcontraxxx

[edit]The contradanza in 6/8 evolved into the clave (not to be confused with the key pattern of the same name), the criolla and the guajira. From the contradanza in 2/4 came the (danza) habanera and the danzón (Carpentier 2001:147).

The danza dominated Cuban music in the second half of the 19th century, though not as completely as the contradanza had in the first half. Two famous Cuban composers in particular, Ignacio Cervantes (1847–1905) and Ernesto Lecuona (1895–1963), used the danza as the basis of some of their most memorable compositions. And, in spite of competition from the danzón, which eventually won out, the danza continued to be composed as dance music into the 1920s. By this time, the charanga had replaced the orquesta típica of the 19th century (Alén 1994:82- example: "Tutankamen" by Ricardo Reverón).

The music and dance of the contradanza/danza are no longer popular in Cuba, but are occasionally featured in the performances of professional or amateur folklore groups.

Sound files

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

[edit]- Legran Orchestra La Comisión de San Roque Habanera Mp3· ISWC: T-042192386-5 2007. Published with the permission of the owner of rights

Discography

[edit]xxxcontraxxx

[edit]- The Cuban Danzon: Its Ancestors and Descendants 1982. Various Artists. Folkways Records - FW04066

Popular adaptations

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

[edit]- The b-side to Kate Nash's 2007 single Foundations, was entitled 'Habanera'.[citation needed]

- Mickey, Donald, Goofy: The Three Musketeers features the song "Chains of Love" which is set to the tune of Habanera.[citation needed]

- Paradiso Girls' song "Who's My Bitch" samples a recording of this song.[citation needed]

- La Paloma[citation needed]

See also

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

[edit]xxxcontraxxx

[edit]Contra dance, a North American folk dance, is also descendant from contredanse.

References

[edit]xxxmixxxx

[edit]- ^ A set group of dance steps that makes up a recognized, named movement.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

cgkmikwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Garofalo, pg. 27

- ^ "[Afro]-Latin rhythms have been absorbed into black American styles far more consistently than into white popular music, despite Latin music's popularity among whites" (Roberts The Latin Tinge 1979: 41).

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1999: 16) Latin Jazz. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ^ Morton, “Jelly Roll” (1938: Library of Congress Recording): "Now in one of my earliest tunes, 'New Orleans Blues,' you can notice the Spanish tinge. In fact, if you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz." The Complete Recordings By Alan Lomax.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 97). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 97).

- ^ Alejo Carpentier cited by John Storm Roberts (1979: 6). The Latin tinge: the impact of Latin American music on the United States. Oxford.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 67). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Orovio, Helio. 1981. Diccionario de la Música Cubana, p.237. La Habana, Editorial Letras Cubanas. ISBN 959-10-0048-0.

- ^ Peñalosa, David (2009: 41). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 69). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Acosta, Leonardo (2003: 5). Cubano Be Cubano Bop; One Hundred Years of Jazz in Cuba. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

- ^ Mauleón (1999: 4) Salsa Guidebook for Piano and Ensemble. Petaluma, California: Sher Music. ISBN 0-9614701-9-4.

- ^ a b c Listen again. Experience Music Project. Duke University Press, 2007. p75 ISBN 978-0-8223-4041-6

- ^ a b c Thompson, Robert Farris. 2006. Tango: the art history of love. Vintage, p117 ISBN 978-1-4000-9579-7

- ^ Peñalosa, David (2009: 41-42). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ^ The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1-56159-284-5

- ^ Peñalosa, David (2009: 41).

- ^ Peñalosa (2009: 42).

- ^ Roberts (1998:50).

- ^ Blatter, Alfred 2007. Revisiting music theory: a guide to the practice. p28 ISBN 0-415-97440-2.

- ^ Garrett, Charles Hiroshi (2008). Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century, p.54. ISBN 9780520254862. Shown in common time and then in cut time with tied sixteenth & eighth note rather than rest.

- ^ Sublette, Ned (2007). Cuba and Its Music, p.134. ISBN 978-1-55652-632-9. Shown with tied sixteenth & eighth note rather than rest.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 55-56). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Coburg, Adrian (2004: 7). "2/2 Makuta" Percusion Afro-Cubana v. 1: Muisca Folklorico. Bern: Coburg.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 20). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1979: 6). The Latin tinge: the impact of Latin American music on the United States. Oxford.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2009: 69). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Acosta, Leonardo (2003: 5). Cubano Be Cubano Bop; One Hundred Years of Jazz in Cuba. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

- ^ Mauleón (1999: 4) Salsa Guidebook for Piano and Ensemble. Petaluma, California: Sher Music. ISBN 0-9614701-9-4.

- ^ derived from the English "country dance"

- ^ Sublette, Ned 2004. Cuba and its music: from the first drums to the mambo. Chicago. p134

- ^ The guaracha was an earlier type of Cuban music which was also sung.

- ^ Grenet, Emilio 1939. Música popular cubana. La Habana.

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1979: 6). The Latin tinge: the impact of Latin American music on the United States. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Carpentier, Alejo 2001 (1945). Music in Cuba. Minneapolis MN.

- ^ Berenguer González, Ramón T. "La Comisión de San Roque" Habanera Mp3· ISWC: T-042192386-5 2007

- ^ Spanish Influence Dances.

- ^ a b "El Choclo" sheet music at TodoTango.

- ^ Collier, Cooper, Azzi and Martin. 1995. Tango! The dance, the song, the story. Thames & Hudson, London. p45 (ISBN 0-500-01671-2) citing Ventura Lynch: La provinciade Buenos Aires hasta la definicion de la cuestion Capital de la Republica. p.16.

- ^ La morocha sheet music at TodoTango.

- ^ a b Baim, Jo 2007. Tango: creation of a cultural icon. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34885-2.

- ^ "La trampera" sheet music at TodoTango.

- ^ Kubik, Gerhard (1999: 52). Africa and the Blues. Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi.

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1999: 12) Latin Jazz. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1999: 16) Latin Jazz. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ^ Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. by W.C. Handy, edited by Arna Bontemps: foreword by Abbe Niles. Macmillan Company, New York; (1941) pages 99,100. no ISBN in this first printing

- ^ Roberts, John Storm 1979. The Latin tinge: the impact of Latin American music on the United States. Oxford.

- ^ Morton, “Jelly Roll” (1938: Library of Congress Recording) The Complete Recordings By Alan Lomax.

- ^ Marsalis, Wynton (2000: DVD n.1). Jazz. PBS

- ^ "Jazz and Math: Rhythmic Innovations", PBS.org. The Wikipedia example shown in half time compared to the source.

- ^ http://sandersmusic.com/bootnote.html?cut=4

- ^ Although the contradanza and danza were musically identical, the dances were different

Further reading

[edit]xxxcontraxxx

[edit]- Alén, Olavo. 1994. De lo Afrocubano a la Salsa. La Habana, Ediciones ARTEX

- Carpentier, Alejo. Music in Cuba. Edited by Timothy Brennan. Translated by Alan West-Durán. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

- Léon, Argeliers. 1974. De la Contradanza al Danzón. In Fernández, María Antonia (1974) Bailes Populares Cubanos. La Habana, Editorial Pueblo y Educación.

- Orovio, Helio. 1981. Diccionario de la Música Cubana. La Habana, Editorial Letras Cubanas. ISBN 959-10-0048-0

- Santos, John. 1982. The Cuban Danzón: Its Ancestors and Descendants, liner notes. Folkways Records - FW04066

External links

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

[edit]- Habanera's blog from Tony Foixench.

- Habanera's website.

- "3-Habanera and danzón" (Cuban Music Website).

xxxhabaxxx

[edit]xxxcontraxxx

[edit]xxxhabaxxx

[edit]===== xxxmixedxxx ===== [[Category:Spanish music]] [[Category:Cuban music]] [[Category:Cuban music history]] [[Category:Cuban styles of music]] [[Category:Rhythm]] [[Category:Dance forms in classical music]]