User:Kchemyoung/sandbox

| Claisen rearrangement | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Rainer Ludwig Claisen |

| Reaction type | Rearrangement reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| Organic Chemistry Portal | claisen-rearrangement |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000148 |

The Claisen rearrangement (not to be confused with the Claisen condensation) is a powerful carbon–carbon bond-forming chemical reaction discovered by Rainer Ludwig Claisen. The heating of an allyl vinyl ether will initiate a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to give a γ,δ-unsaturated carbonyl.

Discovered in 1912, the Claisen rearrangement is the first recorded example of a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement.[1][2][3] Many reviews have been written.[4][5][6][7]

Mechanism

[edit]The Claisen rearrangement is an exothermic, concerted (bond cleavage and recombination) pericyclic reaction. Woodward–Hoffmann rules show a suprafacial, stereospecific reaction pathway. The kinetics are of the first order and the whole transformation proceeds through a highly ordered cyclic transition state and is intramolecular. Crossover experiments eliminate the possibility of the rearrangement occurring via an intermolecular reaction mechanism and are consistent with an intramolecular process.[8][9]

There are substantial solvent effects observed in the Claisen rearrangement, where polar solvents tend to accelerate the reaction to a greater extent. Hydrogen-bonding solvents gave the highest rate constants. For example, ethanol/water solvent mixtures give rate constants 10-fold higher than sulfolane.[1][2] Trivalent organoaluminium reagents, such as trimethylaluminium, have been shown to accelerate this reaction.[10][11]

Variations

[edit]Aromatic Claisen rearrangement

[edit]The first reported Claisen rearrangement is the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of an allyl phenyl ether to intermediate 1, which quickly tautomerizes to an ortho-substituted phenol.

Meta-substitution affects the regioselectivity of this rearrangement.[12][13] For example, electron withdrawing groups (e.g. bromide) at the meta-position direct the rearrangement to the ortho-position (71% ortho product), while electron donating groups (e.g. methoxy), direct rearrangement to the para-position (69% para product). Additionally, presence of ortho-substituents exclusively leads to para-substituted rearrangement products (tandem Claisen and Cope rearrangement).[14]

If an aldehyde or carboxylic acid occupies the ortho or para positions, the allyl side-chain displaces the group, releasing it as carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide, respectively.[15][16]

Bellus–Claisen rearrangement

[edit]The Bellus–Claisen rearrangement is the reaction of allylic ethers, amines, and thioethers with ketenes to give γ,δ-unsaturated esters, amides, and thioesters.[17][18][19] This transformation was serendipitously observed by Bellus in 1979 through their synthesis of a key intermediate of an insecticide, pyrethroid. Halogen substituted ketenes (R1, R2) are often used in this reaction for their high electrophilicity. Numerous reductive methods for the removal of the resulting α-haloesters, amides and thioesters have been developed.[20][21] The Bellus-Claisen offers synthetic chemists a unique opportunity for ring expansion strategies.

Eschenmoser–Claisen rearrangement

[edit]The Eschenmoser–Claisen rearrangement proceeds by heating allylic alcohols in the presence of N,N-dimethylacetamide dimethyl acetal to form γ,δ-unsaturated amide. This was developed by Albert Eschenmoser in 1964.[22][23] Eschenmoser-Claisen rearrangement was used as a key step in the total synthesis of morphine.[24]

Mechanism:[14]

Ireland–Claisen rearrangement

[edit]The Ireland–Claisen rearrangement is the reaction of an allylic carboxylate with a strong base (such as lithium diisopropylamide) to give a γ,δ-unsaturated carboxylic acid.[25][26][27] The rearrangement proceeds via silylketene acetal, which is formed by trapping the lithium enolate with chlorotrimethylsilane. Like the Bellus-Claisen (above), Ireland-Claisen rearrangement can take place at room temperature and above. The E- and Z-configured silylketene acetals lead to anti and syn rearranged products, respectively.[28] There are numerous examples of enantioselective Ireland-Claisen rearrangements found in literature to include chiral boron reagents and the use of chiral auxiliaries.[29][30]

Johnson–Claisen rearrangement

[edit]The Johnson–Claisen rearrangement is the reaction of an allylic alcohol with an orthoester to yield a γ,δ-unsaturated ester.[31] Weak acids, such as propionic acid, have been used to catalyze this reaction. This rearrangement often requires high temperatures (100 to 200 °C) and can take anywhere from 10 to 120 hours to complete.[32] However, microwave assisted heating in the presence of KSF-clay or propionic acid have demonstrated dramatic increases in reaction rate and yields.[33][34]

Mechanism:[14]

Photo-Claisen rearrangement

[edit]The photo-Claisen rearrangement is closely related to the photo-Fries rearrangement, proceeding via a radical mechanism. Aryl ethers undergo the photo-Claisen, while the photo-Fries is experiences by aryl esters.[35]

Hetero-Claisens

[edit]Aza–Claisen

[edit]An iminium can serve as one of the pi-bonded moieties in the rearrangement.[36]

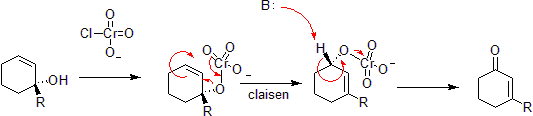

Chromium oxidation

[edit]Chromium can oxidize allylic alcohols to alpha-beta unsaturated ketones on the opposite side of the unsaturated bond from the alcohol. This is via a concerted hetero-Claisen reaction, although there are mechanistic differences since the chromium atom has access to d- shell orbitals which allow the reaction under a less constrained set of geometries.[37][38]

Chen–Mapp reaction

[edit]The Chen–Mapp reaction also known as the [3,3]-Phosphorimidate Rearrangement or Staudinger–Claisen Reaction installs a phosphite in the place of an alcohol and takes advantage of the Staudinger reduction to convert this to an imine. The subsequent Claisen is driven by the fact that a P=O double bond is more energetically favorable than a P=N double bond.[39]

Overman rearrangement

[edit]The Overman rearrangement (named after Larry Overman) is an irreversible rearrangement of allylic trichloroacetimidates to allylic trichloroacetamides.[40][41][42] This reaction can be catalyzed by mercuric salts, protic and Lewis acids.[43][44]

Zwitterionic Claisen rearrangement

[edit]Unlike typical Claisen rearrangements which require heating, zwitterionic Claisen rearrangements take place at or below room temperature. The acyl ammonium ions are highly selective for Z-enolates under mild conditions.[45][46]

Claisen rearrangement in nature

[edit]The enzyme Chorismate mutase (EC 5.4.99.5) catalyzes the Claisen rearrangement of chorismate ion to prephenate ion, a key intermediate in the shikimic acid pathway (the biosynthetic pathway towards the synthesis of phenylalanine and tyrosine).[47]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Claisen, L. (1912). "Über Umlagerung von Phenol-allyläthern in C-Allyl-phenole". Chemische Berichte. 45 (3): 3157–3166. doi:10.1002/cber.19120450348.

- ^ a b Claisen, L.; Tietze, E. (1925). "Über den Mechanismus der Umlagerung der Phenol-allyläther". Chemische Berichte. 58 (2): 275. doi:10.1002/cber.19250580207.

- ^ Claisen, L.; Tietze, E. (1926). "Über den Mechanismus der Umlagerung der Phenol-allyläther. (2. Mitteilung)". Chemische Berichte. 59 (9): 2344. doi:10.1002/cber.19260590927.

- ^ Hiersemann, M.; Nubbemeyer, U. (2007) The Claisen Rearrangement. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-30825-3

- ^ Rhoads, S. J.; Raulins, N. R. (1975). "The Claisen and Cope Rearrangements". Org. React. 22: 1–252. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or022.01. ISBN 0471264180.

- ^ Ziegler, F. E. (1988). "The thermal, aliphatic Claisen rearrangement". Chem. Rev. 88 (8): 1423–1452. doi:10.1021/cr00090a001.

- ^ Wipf, P. (1991). "Claisen Rearrangements". Comp. Org. Syn. 5: 827–873. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00140-2. ISBN 978-0-08-052349-1.

- ^ Hurd, C. D.; Schmerling, L. (1937). "Observations on the Rearrangement of Allyl Aryl Ethers". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 59: 107. doi:10.1021/ja01280a024.

- ^ Francis A. Carey; Richard J. Sundberg (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part A: Structure and Mechanisms. Springer. pp. 934–935. ISBN 978-0-387-44897-8.

- ^ Goering, H. L.; Jacobson, R. R. (1958). "A Kinetic Study of the ortho-Claisen Rearrangement1". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (13): 3277. doi:10.1021/ja01546a024.

- ^ White, W. N.; Wolfarth, E. F. (1970). "The o-Claisen rearrangement. VIII. Solvent effects". J. Org. Chem. 35 (7): 2196. doi:10.1021/jo00832a019.

- ^ White, William; and Slater, Carl, William N.; Slater, Carl D. (1961). "The ortho-Claisen Rearrangement. V. The Products of Rearrangement of Allyl m-X-Phenyl Ethers". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 26 (10): 3631–3638. doi:10.1021/jo01068a004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gozzo, Fábio; Fernandes, Sergio; Rodrigues, Denise; Eberlin, Marcos; and Marsaioli, Anita, Fábio Cesar; Fernandes, Sergio Antonio; Rodrigues, Denise Cristina; Eberlin, Marcos Nogueira; Marsaioli, Anita Jocelyne (2003). "Regioselectivity in Aromatic Claisen Rearrangements". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 68 (14): 5493–5499. doi:10.1021/jo026385g. PMID 12839439.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c László Kürti; Barbara Czakó (2005). Strategic Applications Of Named Reactions In Organic Synthesis: Background And Detailed Mechanics: 250 Named Reactions. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-429785-2. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Adams, Rodger (1944). Organic Reactions, Volume II. Newyork: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Claisen, L.; Eisleb, O. (1913). "Über die Umlagerung von Phenolallyläthern in die isomeren Allylphenole". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 401 (1): 90. doi:10.1002/jlac.19134010103.

- ^ Malherbe, R.; Bellus, D. (1978). "A New Type of Claisen Rearrangement Involving 1,3-Dipolar Intermediates. Preliminary communication". Helv. Chim. Acta. 61 (8): 3096–3099. doi:10.1002/hlca.19780610836.

- ^ Malherbe, R.; Rist, G.; Bellus, D. (1983). "Reactions of haloketenes with allyl ethers and thioethers: A new type of Claisen rearrangement". J. Org. Chem. 48 (6): 860–869. doi:10.1021/jo00154a023.

- ^ Gonda, J. (2004). "The Belluš–Claisen Rearrangement". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43 (27): 3516–3524. doi:10.1002/anie.200301718.

- ^ Edstrom, E (1991). "An unexpected reversal in the stereochemistry of transannular cyclizations. A stereoselective synthesis of (±)-epilupinine". Tetrahedron Letters. 32 (41): 5709–5712. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)93536-6.

- ^ Bellus (1983). "Reactions of haloketenes with allyl ethers and thioethers: a new type of Claisen rearrangement". JOC. 48 (6): 860–869. doi:10.1021/jo00154a023.

- ^ Wick, A. E.; Felix, D.; Steen, K.; Eschenmoser, A. (1964). "CLAISEN'sche Umlagerungen bei Allyl- und Benzylalkoholen mit Hilfe von Acetalen des N, N-Dimethylacetamids. Vorläufige Mitteilung". Helv. Chim. Acta. 47 (8): 2425–2429. doi:10.1002/hlca.19640470835.

- ^ Wick, A. E.; Felix, D.; Gschwend-Steen, K.; Eschenmoser, A. (1969). "CLAISEN'sche Umlagerungen bei Allyl- und Benzylalkoholen mit 1-Dimethylamino-1-methoxy-äthen". Helv. Chim. Acta. 52 (4): 1030–1042. doi:10.1002/hlca.19690520418.

- ^ Guillou, C (2008). "Diastereoselective Total Synthesis of (±)-Codeine". Chem. Eur. J. 14 (22): 6606–6608. doi:10.1002/chem.200800744. PMID 18561354.

- ^ Ireland, R. E.; Mueller, R. H. (1972). "Claisen rearrangement of allyl esters". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 94 (16): 5897. doi:10.1021/ja00771a062.

- ^ Ireland, R. E.; Willard, A. K. (1975). "The stereoselective generation of ester enolates". Tetrahedron Lett. 16 (46): 3975–3978. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91213-9.

- ^ Ireland, R. E.; Mueller, R. H.; Willard, A. K. (1976). "The ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. Stereochemical control through stereoselective enolate formation". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (10): 2868. doi:10.1021/ja00426a033.

- ^ Ireland, R. E. (1991). "Stereochemical control in the ester enolate Claisen rearrangement". JOC. doi:10.1021/jo00002a030.

- ^ Enders, E (1996). "Asymmetric [3.3]-sigmatropic rearrangements in organic synthesis". Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 7 (7): 1847–1882. doi:10.1016/0957-4166(96)00220-0.

- ^ Corey, E (1991). "Highly enantioselective and diastereoselective Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of achiral allylic esters". JACS. 113 (10): 4026–4028. doi:10.1021/ja00010a074.

- ^ Johnson, W. S.; et al. (1970). "Simple stereoselective version of the Claisen rearrangement leading to trans-trisubstituted olefinic bonds. Synthesis of squalene". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92 (3): 741. doi:10.1021/ja00706a074.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Fernandes, R. A. (2013). "The Orthoester Johnson–Claisen Rearrangement in the Synthesis of Bioactive Molecules, Natural Products, and Synthetic Intermediates – Recent Advances". Eur JOC. 2014 (14): 2833–2871. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201301033.

- ^ Huber, R. S. (1992). "Acceleration of the orthoester Claisen rearrangement by clay catalyzed microwave thermolysis: expeditious route to bicyclic lactones". JOC. 57 (21): 5778–5780. doi:10.1021/jo00047a041.

- ^ Srikrishna, A (1995). "Application of microwave heating technique for rapid synthesis of γ,δ-unsaturated esters". Tetrahedron. 51 (6): 1809–1816. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(94)01058-8.

- ^ IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). XML on-line corrected version: http://goldbook.iupac.org (2006–) created by M. Nic, J. Jirat, B. Kosata; updates compiled by A. Jenkins. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. doi:10.1351/goldbook

- ^ Kurth, M. J.; Decker, O. H. W. (1985). "Enantioselective preparation of 3-substituted 4-pentenoic acids via the Claisen rearrangement". J. Org. Chem. 50 (26): 5769–5775. doi:10.1021/jo00350a067.

- ^ Dauben, W. G.; Michno, D. M. (1977). "Direct oxidation of tertiary allylic alcohols. A simple and effective method for alkylative carbonyl transposition". J. Org. Chem. 42 (4): 682. doi:10.1021/jo00424a023.

- ^ "(R)-(+)-3,4-Dimethylcyclohex-2-en-1-one ((R)-(+)-3,4-Dimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one)". Organic Syntheses. 82: 108. 2005

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 40 (help). - ^ Chen, B.; Mapp, A. (2005). "Thermal and catalyzed 3,3-phosphorimidate rearrangements". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (18): 6712–6718. doi:10.1021/ja050759g. PMID 15869293.

- ^ Overman, L. E. (1974). "Thermal and mercuric ion catalyzed [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of allylic trichloroacetimidates. 1,3 Transposition of alcohol and amine functions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 96 (2): 597–599. doi:10.1021/ja00809a054.

- ^ Overman, L. E. (1976). "A general method for the synthesis of amines by the rearrangement of allylic trichloroacetimidates. 1,3 Transposition of alcohol and amine functions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (10): 2901–2910. doi:10.1021/ja00426a038.

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 6, p.507; Vol. 58, p.4 (Article)

- ^ Hussein, F (1960). "Ortho Esters, Imidic Esters and Amidines. VIII. Thermal and Acid-catalyzed Rearrangements of Allylic N-Phenylformimidates". JACS. 82 (8): 1950–1953. doi:10.1021/ja01493a028.

- ^ Hennrich, N (2006). "Imidoester, V. Die Umlagerung von Trichloracetimidaten zu N-substituierten Säureamiden". Eur JIC. 94 (4): 976–989. doi:10.1002/cber.19610940414.

- ^ Yu, C.-M.; Choi, H.-S.; Lee, J.; Jung, W.-H.; Kim, H.-J. (1996). "Self-regulated molecular rearrangement: Diastereoselective zwitterionic aza-Claisen protocol". J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (2): 115–116. doi:10.1039/p19960000115.

- ^ Nubbemeyer, U. (1995). "1,2-Asymmetric Induction in the Zwitterionic Claisen Rearrangement of Allylamines". J. Org. Chem. 60 (12): 3773–3780. doi:10.1021/jo00117a032.

- ^ Ganem, B. (1996). "The Mechanism of the Claisen Rearrangement: Déjà Vu All over Again". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 35 (9): 936–945. doi:10.1002/anie.199609361.

See also

[edit]

Category:Rearrangement reactions Category:Name reactions Category:Substitution reactions Category:Carbon-carbon bond forming reactions