User:Kawuquk/sandbox

Kawuquk (talk) 21:27, 19 March 2012 (UTC)

‘’’Demoralization’’’ is a means of psychological warfare in which one party (normally a state or agency thereof) attempts to damage the morale of an identified belligerent.

Importance of morale

[edit]Morale is often perceived as a necessary precursor to success in international relations because success most often goes to those who believe in their cause, as they more easily maintain a positive outlook that contributes to their ability to work harder for the cause.[1] High morale can directly contribute to “an economy of food, textiles, fuel, and other commodities, and to stimulate recruiting, employment in war industries, service in relief work, and the purchase of bonds.”[2] Writing in 1965, French philosopher and sociologist Jacques Ellul described the importance of morale in modern society by saying:

| “ | The modern citizen is asked to participate in wars such as have never been seen before. All men must prepare for war, and for a dreadful type of war at that – dreadful because of its duration, the immensity of its operations, its tremendous losses, and the atrocity of the means employed. Moreover, participation in war is no longer limited to the duration of the war itself; there is the period of preparation for war, which becomes more and more intense and costly. Then there is the period in which to repair the ravages of war. People really live in a permanent atmosphere of war, and a superhuman war in every respect. Nowadays everybody is affected by war; everybody lives under its threat…The more demanded of man, the more powerful must be those motivations.[3] | ” |

Though variations are possible, the most common indicators of high moral are determination, enthusiasm, self-confidence, and a relative absence of criticism or complaint.[4] While contributors to the level of morale are essentially endless, common examples consist of the level to which: individuals identify with a nation or cause; have their basic needs of food, clothing, shelter met; have confidence in the justness of their cause; have confidence in the ability of their cause to overcome obstacles; the means through which authorities instill discipline; and a sense of unity with other supporters of the cause.[5]

Demoralization as means of psychological warfare

[edit]

In an environment in which two belligerents compete, the chances of success greatly diminish if those whose actions are necessary don’t have faith in the justness of the cause or its chance for success, are discouraged, morally defeated, disconsolate, uncooperative, sullen, inattentive, or lazy.[6] Demoralization can be used to lessen the chances of success for an opponent by fostering these attitudes, and can generally be done in one of two ways: demoralization through objective conditions or demoralization through perception.[7] Demoralization through objective conditions most commonly takes the form of a military defeat on the battlefield that has tangible consequences directly resulting in the indicators of a demoralized party, though it can also result from an adverse physical environment where basic needs go unmet.[8] Demoralization through perception, however, is the most commonly referred to means of demoralization even though its operation and results, like political warfare and psychological warfare in general, are the most difficult to gauge.[9] This is the form of demoralization that is referred to as a tool of psychological warfare, and it is most commonly implemented through various forms of propaganda.[10] Propaganda as a tool of demoralization refers to influencing opinion through significant symbols, through means such as rumors, stories, pictures, reports, and other means of social communication.[11] Other means of political and psychological warfare – such as deception, disinformation, agents of influence, or forgeries - may also be used to destroy morale through psychological means so that a belligerent starts questioning the validity of their beliefs and actions.[12]

Means of strategic demoralization

[edit]While demoralization may use propaganda, deception, disinformation, agents of influence, forgeries, or any other political warfare tool in isolation to accomplish its ends, a strategic demoralization effort will use more than one of these means as determined by its target and will not limit itself to the strict limits of attacking another belligerent’s morale.[13] A strategic demoralization campaign will navigate what Harold D. Lasswell describes as roughly three avenues of implementation: divert the hatred normally directed towards the enemy, thereby denying a unified outlet of frustration; sow seeds of self-doubt (classic demoralization); and provide a new focus of hatred and frustration.[14] These avenues of a strategic demoralization campaign need not be done in a particular order or with an egalitarian focus, as the target and situation will dictate the best strategy for implementation.[15]

Denial of an enemy image

[edit]An important precursor to successful demoralization is an effort to deny the target the ability to project their frustrations and hatred upon a common enemy.[16] Such efforts will affect the tendency of the target’s citizenry to project their discontent towards a common enemy identified by their government.[17] As a result, frustrations will build until it is necessary to divert them elsewhere, and seeds of doubt are sewn in the minds of the citizenry who now question the capability of their leadership in identifying the most ominous threat.[18]

The operations of the German Gazette des Ardennes, published in occupied areas of France during WWI, are an example of this aspect of strategic demoralization.[19] The Gazette des Ardennes regularly published propaganda articles that sought to deny the French of a German enemy image.[20] These articles would carry such themes as: the Kaiser has always been known and respected for promoting peace, even among the British and French intellectual elite; the Kaiser is a kind and gentle family man; “all the stories about the German barbarities are poisonous lies”; German occupying soldiers are kind to and loved by French children; Germans have an irrepressible love of music, religion, and morality that permeates wherever they are, etc.[21] These themes are illustrative of “defense by denial.”[22] It is also possible to use “defense by admission accompanied by justification.”[23]Using this technique, the Gazette des Ardennes would admit that a German atrocity occurred, but then publish accounts that the event was exaggerated in earlier reports and that such events occurred in every army, and nowhere did they occur less often than in the German army.[24] Articles in Gazette des Ardennes that attempted to justify German unrestricted submarine warfare as an unavoidable consequence of the British blockade are also examples of defense by admission and justification.[25]

Sowing seeds of doubt and anxiety

[edit]Causing self-doubt or doubt in a cause is the simple definition most commonly ascribed to demoralization.[26] Though this is only one aspect of a successful strategic demoralization campaign, it is the most pronounced and essential part.[27] As noted by Harold D. Lasswell, “the keynote in the preliminary spade work is the unceasing refrain: Your cause is hopeless. Your blood is spilt in vain.”[28] Propaganda can be an indispensable tool in fostering an environment of doubt and anxiety.[29] Propaganda may be used to ensure the antagonist is the most feared party, give a feeling of non-worth to the target, exploit internal fissures inherent within the target group, or use the element of surprise to show a target population that their leadership and cause are unable to protect them from the impending enemy threat.[30]

Many studies have been conducted that indicate fear is one of the most widespread psychological traits, and this trait can be manipulated for the purposes of demoralization if it can be expanded into anxiety.[31] In order for anxiety to demoralize it must result in a distancing of the individual or group from their cause or leadership because they no longer believe them capable of offering a solution to the source of their anxiety.[32] Real and conscious threats that normally inspire disquiet and fear can be made to cause anxiety and borderline neurosis through the use of such propaganda tools as fables and rumors.[33] Using multiple tools of political warfare – such as deception, disinformation, agents of influence, or forgeries – can expedite the onset of anxiety by overwhelming the target with a constant onslaught of information saying their current cause or leadership is incapable of relieving the anxiety now felt.[34] This anxiety cannot be calmed through a rational explanation of facts, and is in fact exacerbated by such an approach.[35] This newly onset anxiety places mass groups of individuals on the border of neurosis and can make them feel conflicts inherent within society or their past.[36] As a result of contradictions and threats, “man feels accused, guilty.”[37] The target will then begin their search for a cause that will provide a sense of righteousness.[38] The pivotal moment of a successful demoralization campaign is when the target is doubt-ridden and anxious, as this is the point at which individual members of a citizenry or group are detached from their current loyalty to their state or cause, and are then able to be focused in another direction more suitable to the antagonist’s needs.[39] [40] If not done properly, this manufactured sense of anxiety can backfire on the antagonist and cause the subject to cling closer to their original cause or government.[41]

Diverting frustrations and hatred to a new target

[edit]The most powerful strategy of demoralization is diversion, though this is an extremely difficult and multifaceted operation.[42] Lasswell notes that, “To undermine the active hatred of the enemy for its present antagonist, his anger must be distracted to a new and independent object, beside which his present antagonist ceases to matter.”[43] Because it is such a distinct change, the diversion of hatred towards a new target is necessarily predicated upon the antagonist both diverting hatred away from themselves and fostering a level of anxiety that cannot be mitigated by their existing cause or leadership.[44] Once the antagonist has met these two precursors of demoralization, they can then “concentrate upon the particular object of animosity about which it is hoped to polarize the sentiment of the enemy.”[45] This diversion of hatred can be towards an ally, towards the enemy’s government or governing class, or directed towards anti-state sentiment to foster secession of minority nationalities if they exist.[46]

The attempt to exacerbate relations between allies is one method of diverting hatred from an enemy, and was attempted by both the Allied and Central Powers in World War I.[47] The Germans made efforts to dig up historical animosity between the French and British, using such themes as: the British were just letting the French bleed for them; the British intended to stay on French soil; offering a German-French alliance against the British; and offering to expand French colonial domain at the expense of the British Empire.[48] Meanwhile, the Allies tried to exacerbate the relationship between Austria-Hungary and Germany, using such themes as: separate peace talks were being held with Austria-Hungary; Austria-Hungary had a plethora of food while Germans starved; Germans thought of Austrians as slaves; and the familiar promise of territorial expansion should Austria-Hungary abandon their German alliance.[49]

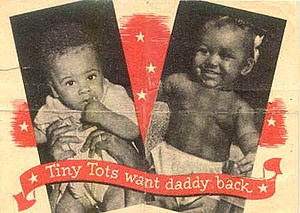

The antagonist can also attempt to divert hatred and frustration upon the target’s government or ruling class, and this is often the most widely attempted method.[50] One technique of diverting frustration in this manner is to convince a target that their government or leadership is committing unjust and immoral acts; this is especially effective if the antagonist can convince their target that their leadership has forced them to commit equally unjust and immoral acts out of trickery or desperation.[51] If successfully and fully implemented, the leadership of a cause can be made sufficiently troublesome to inspire revolution during which time there will be insufficient capacity to exercise active hatred towards the external enemy.[52] Diverting frustration to one’s own leadership is often the method most commonly seen in wartime propaganda, as the photographs below attest. With the implementation of modern warfare in World War I and all its associated stresses, “every belligerent took a hand in the perilous business of fomenting dissension and revolution abroad, reckless of the possible repercussions of a successful revolt.”[53] Example from WWI included: German forces providing revolutionary literature to Russian prisoners of war that were expected to return through exchange or release; French use of propaganda leaflets to demonstrate how unaffected by war the Kaiser and his family were; technical encouragement and amplification of national dissent; Wilsonian propaganda stressing peaceful settlement terms; British planting of stories attesting to underground German resistance movements and their subsequent oppression by the German government; propaganda deflecting war guilt; propaganda exposing or exaggerating the desired post-war peace terms; and the promotion of the belief that infidelity was rampant among soldiers and their families back home.[54]

Finally, the antagonist can attempt to divert frustration towards the growth of secessionist causes, though this is only possible in heterogeneous nations.[55] Under this method, attempts are made to fan the flames of discontent one segment of the nation feels towards another.[56] An example of this was the Congress of Oppressed Hapsburg Nationalities that met in Rome in April 1918, at which all delegates to the Convention signed a Declaration of Independence and whose actions were widely reported in US and European circles.[57] Another successful example of this was the encouragement of Zionism as a means of securing Jewish support for World War I via the Balfour Declaration. The Central Powers of WWI likewise tried to encourage Ukrainian, Irish, Egyptian, North African, and Indian secessionist movements, though all of these efforts ultimately failed.[58]

Tactics of pursuing demoralization

[edit]

There are many tactics of pursuing a strategy of demoralization, with the nature of the target and the environment at the time determining the best method to employ.[59] Below is a non-exhaustive list that demonstrates some tactics of pursuing demoralization, though any tactic of political and psychological warfare may be used in pursuit of demoralization as appropriate to the situation:

- Insertions into neutral press[60]

- Direct transmission (through publications or radio)[61]

- Books and pamphlets (such as J’accuse)[62]

- Forgeries, whether they be forged letters from home inspiring homesickness or forged government documents[63]

- Tactical delivery systems (airplane or balloon drops, “trench mortars”)[64]

- Smuggling (use of printed propaganda for packing materials, camouflaging propaganda to appear as currency so it may be carried about freely)[65]

- Deception[66]

- Disinformation[67]

- Agents of influence[68]

Defense against demoralization

[edit]Morale can be difficult to maintain in large part due to the diffuse nature of demoralization attacks, though a strong leadership can largely mitigate any such attacks against their group’s morale.[69] Morale will quickly deteriorate if members of the group perceive themselves as victims of injustice or indifference on part of their leadership, or if they perceive their leadership as being acting ineptly, ignorantly, or in pursuit of personal ambition.[70] As noted by Angello Codevilla, the clearest indicators that morale can withstand a demoralization campaign are also hallmarks of a well-led organization, and can be explained through five main questions:

- Do the constituent parts of the group fear their own leadership more than the enemy? This can be either an authoritarian type of fear or a more democratic type of fear where the members of a group fear contributing to the failure of their cause.[71]

- Do the constituent parts of the group feel appreciated by their leadership? No human will work to their full potential if they do not feel appreciated, but those who feel appreciated will contribute remarkable amounts, including sacrifice of life.[72]

- Do the constituent parts of the group feel their contributions are important, and that others depend on their continued effort towards the cause? This is dependent on leadership engendering a hope of success if each member does their part, but excess attempts to inspire can invite cynicism.[73]

- Do the constituent parts of the group of habits of loyalty and camaraderie? If so, high morale can be maintained in the most difficult circumstances out of a desire to not disappoint or endanger others.[74]

- Do the constituent parts of the group have faith in their leaders and the chances of success? As Codevilla notes, “If the two disappear, soldiers tend to believe they have been sold out and throw away their weapons.” Credibility is the bedrock of defense against demoralization, but unwelcome surprise is the greatest threat to morale.[75]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

See also

[edit]- Communist front

- Fellow traveler

- Foreign Agents Registration Act

- Front organization

- Mole (espionage)

- Useful idiot

References

[edit]- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 88.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 9.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 142.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 8.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 8.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 88.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 8-9.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 8.

- ^ Murray Dyer, The Weapon on the Wall: Rethinking Psychological Warfare (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1959), pg. 7.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 8.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 9.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. xiii.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 161.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163-177.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 162.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 162.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 162-163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 161-162.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 162.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 162-163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 189.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 164.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 164.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89-90.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89-90.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153-155.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153-155.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153-155.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153-155.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 155.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153-155.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 153-155.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 153.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 163.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 167.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 167-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 167-168.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 167-168.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 168-169.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 169.

- ^ Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1973), pg. 189.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 169.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 169.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 169-173.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 173.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 173.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 175-178.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 175-178.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 164-167.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in World War I (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1971), pg. 178-184.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89-90.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 88.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 89.

- ^ Angelo Codevilla and Paul Seabury, War: Ends and Means (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006), pg. 90.

External links

[edit]- Interview with Ralph de Toledano

- Van Hook, James C. (2005). "Treasonable Doubt: The Harry Dexter White Spy Case (review)". Studies in Intelligence. 49 (1). ISSN 1527-0874.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Agents of Influence—from Soviet Active Measures in the "Post-Cold War Era" 1988–1991

- United States Department of Justice - The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA)