User:KYPark/005

Table of Contents

WHAT WHY HOW 1. INTRODUCTION 2. THE LINE OF ATTACK 3. SYSTEMS VS. USERS 3.1 Discrimination 3.2 Prediction 4. DOCUMENTS VS. SURROGATES 5. THE THEORY OF INTERPRETATION 5.1 Denotation and Connotation 5.2 The Theory of Ogden and Richards 5.3 Implications for Information Retrieval 6. PROPOSAL FOR FILE ORGANIZATION 6.1 Incentives 6.2 Extracts as Indexing Sources 6.3 Extracts as Review Sources 7. CONCLUSION 8. REFERENCES

| Contents |

|---|

5. THE THEORY OF INTERPRETATION

[edit]5.1 Denotation and Connotation

[edit]We are free to think of anything. [1] [2] At one moment we think of the trees in the garden; at another, of the tomorrow's weather; at still another, of the past experience. These things that we think of, whether existent or non-existent, substantial or imaginary, true or false, may be said to be fairly stable in contrast to our free thoughts. The trees in the garden must be there dropping leaves, even while we stop thinking of them. [3] Thus we can freely organize or map our thoughts [4] upon this stable background. [5] [6] [T]

We invent symbols* with which to express or map our thoughts on things. In isolation we are free to invent and use any symbols to express our thoughts. In a society where we should associate, cooperate, share, or communicate with other people,8 we have two options. That is, either to dictate our own invention or to obey the social rule. Small babies would begin with dictations, e.g., crying out instinctively to express their desire. However, they cannot merely dictate. That would be admittedly too limiting. Far more required of them and far more convenient in most cases is to conform to the social rule. They learn to practice it gradually but never completely. Even when grown up, dictations are necessary. As a matter of fact, the two options are normally intermingled, but eventually separable.

- * By symbol is meant any unit of communication as a whole, regardless of its parts or constitutes. For example, a word, a phrase, a sentence, a journal article, or even a nonsensical string of words under consideration, as far as it is intended to convey some definite thought or idea. The term 'sign' may be broader than 'symbol'. For example, any sense-data or stimuli to organism may be treated as signs.

The social rule on how to use symbols has evolved from among people, somewhat loosely and still changing. Truly, people have been inventing, elaborating, and using more and more convenient symbols for more efficient communication. The speaker expects the listener to receive the symbol that is substantially imparted or communicated. However, the speaker's real expectation is that the listener would share the same thought and direct to the same thing that the speaker has in mind. Largely, this expectation is met when the speaker conforms to the well-established social rule, e.g., grammar and dictionary. Then the majority understand him unanimously; communication is clear-cut. In this case the meaning of such a symbol may be said to be denotative, explicit, or extensional. Refer to a dictionary for these words (Table 2).

On the other hand, communication does not appear as simple as that. Indeed, communication as a whole is a loose affair. Ambiguous and misleading expressions, misunderstandings and different interpretations, and so on. Supposing that someone intends to convey a definite thought or story with the following word string8:

- woman, street, crowd, traffic, noise, haste, thief, bag, loss, scream, police, .....

which looks almost nonsensical as a whole. Then, what will happen to us listeners? We have a dictionary, but we cannot simply sum up the meanings of individual words. That "a whole is more than the sum of the parts" is too plain a saying. There seems to be no grammar to which the speaker might have conformed. He merely suggests rather than tells the story, which in other words is implied or implicit in the word string, i.e., symbol. From this awkward symbol we can guess the story with varying accuracies, if we are ready to take risks. In this case, the meaning of such a symbol may be said to be connotative, implicit, or intensional. [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] Again, refer to a dictionary for these words (Table 2).

5.2 The Theory of Ogden and Richards

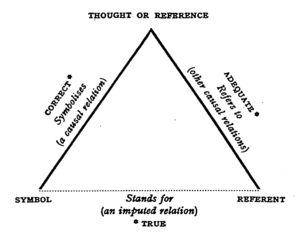

[edit]When we communicate our thoughts about things, we use signs. That is to say, three factors - a thought, a thing, and a sign - are essentially involved in any communication event, either speaking or listening. [14] [15] [16] Ogden and Richards9 place the three factors at the corners of a triangle, where the relations between these factors are represented by the sides, as shown in Figure 3. They recognize that there are causal, direct relations between a sign and a thought, and between a thought and a thing. But, they insist, the relation between a sign and a thing is merely "imputed" as opposed to the causal relations; it holds only indirectly round the two sides of the triangle. they further insist that it is because of this imputed relation that most of the language problems arise. Signs are instruments subjected to thinking or interpretation; they can be related to things only through thinking, or more specifically through interpretation.

Things and experiences are also interpreted; they are treated as signs. Thus, through all our life, we interpret signs in the widest sense, with few exceptions. Then, what happens when we interpret signs? Ogden and Richards9 generalize the process of sign interpretations as follows:

- The effects upon the organism due to any sign which may be any stimulus from without, or any process taking place within, depend upon the past history of the organism, both generally and in a more precise fashion. In a sense, no doubt, the whole past history is relevant; but there will be some among the past events in that history which more directly determine the value of the present agitation than others.

For example, a dog, on hearing the dinner bell, interprets the bell sounds as a sign and runs into the dining room. He can do so owing to the past experience in which clumps of events -- Bells, savors, longing for food, etc. -- have recurred "nearly uniformly." Such a clump of events may be called an external context. And the mental events, occurring in the dog which can link merely the present bell sound together with the past experience of bells-savors-longings, may be called a psychological context. To define more precisely:

- A context is a set of entities (things or events) related in a certain way; these entities have each a character such that other sets of entities occur having the same characters and related by the same relation; and these occur 'nearly uniformly.' [18]

Contexts occur more or less uniformly; that is to say, the constitutive characters of a context recur with uncertainty or with a probability. It follows that the context is said to be determinative with respect to one character if both characters are closely related. By taking very general constitutive characters and uniting relations, we have contexts of high probability; we can increase the probability of a context by adding suitable members. Thus we react the recurring part of the context in the same way as we did the whole context. Experience recurs in contexts which recur more or less uniformly, and interpretation is only possible in these recurring contexts.

- The notion of relevance is of great importance in the theory of meaning. A consideration (notion, idea) or an experience, we shall say, is relevant to an interpretation when it forms part of the psychological context which links other contexts together in the peculiar fashion in which interpretation so links them.*

- * "Other psychological linkings of external contexts are not essentially different from interpretation, but we are only here concerned with the cognitive aspect of mental process."

Finally, Ogden and Richards9 attempt to narrow down their implications by applying the context theory of interpretation [19][20] [21] to the use of words at different levels; from simple recognition of sounds as words to critical interpretation of words.

- With most thinkers, however, the symbol seems to be less essential. It can be dispensed with, altered within limits and is subordinate to the reference for which it is a symbol. For such people, for the normal case that is to say, the symbol is only occasionally part of the psychological context required for the references. No doubt for us all there are references which we can only make by the aid of words, i.e., by contexts of which words are members, but these are not necessarily the same for people of different mental types and levels; and further, even for one individual a reference which may be able to dispense with a word on one occasion may require it, in the sense of being impossible without it, on another. On different occasions quite different contexts may be determinative in respect of similar references. It will be remembered that two references, which are sufficiently similar in essentials to be regarded as the same for practical purposes, may yet differ very widely in their minor features. The contexts operative may include additional supernumerary members. But any one of these minor features may, through a change in the wider contexts upon which these narrower contexts depend, become an essential element instead of a mere accompaniment. This appears to happen in the change from word-freedom, when the word is not an essential member of the context of the reference, to word-dependence, when it is.

5.3 Implications for Information Retrieval

[edit]Ogden and Richards9 do not specify contexts in the triangle in Figure 3. Cherry8 modifies the diagram as shown in Figure 4a. We shall further modify it as shown in Figure 4b, and say that the triangle is surrounded by the external context and contains the psychological context inside. Still, the diagram only represents either speaking or listening. Thus we shall develop the diagram further in the following.

A unit communication, including both speaking and listening, may be represented by the diagram as shown in Figure 5. The arrows and the corresponding words may be convenient to represent the functional flow in a unit communication. Thus we shall say that:

- In speaking

- A thing initiates a thought which in turn adopts a sign.

- In listening

- A sign evokes a thought which in turn directs to a thing.

If there arises no physical distortion between two signs, then the sign in speaking and the sign in listening will be the same, or get together. If the listener's thought directs to the same thing that initiated the speaker's thought, then we shall have an ideal unit communication as shown in Figure 6.

We may better develop the diagram further in order to represent communication situations which are more complex than a unit communication. And we shall normally approximate individual units of communication to ideal units as shown in Figure 6.

Let us take for example the password game. The questioner, thinking of WATCHWORD, gives a symbol 'watchword' to the intermediary, who in turn gives another symbol 'password' to the answerer. Before and after translation from 'watchword' into 'password,' the intermediary's thoughts I and I' should be different such that I corresponds to WATCHWORD and I' to PASSWORD. Therefore, the answerer's thought should direct first to PASSWORD, and then to WATCHWORD which is the correct answer. The answerer should make a guess that is the reverse of translation. This password game is illustrated in Figure 7. Communication between the questioner and the intermediary makes an ideal unit, and that between the intermediary and the answerer makes another ideal. These two ideal units are separated by a communication gap which should be overcome by the answerer's guesswork. In corollary, complexity of communications involved in information retrieval may be shown as the diagram in Figure 8.

AFTERTHOUGHTS

[edit]- See also

- Colin Cherry

- Human communication

- C. K. Ogden

- I. A. Richards

- The Meaning of Meaning

- Triangle of reference

- Connotation, Implication, Implicature

- Denotation, Explication, Explicature

- ^ "We are free to think of anything."

Some thinkers attack the problem of free will by distnguishing different notions of freedom or meaning of the word 'free'. In one sense we are free -- free enough for concepts of morality and responsibility to come into play. In another sense we are not free, and all that happens now is determined by what has happened earlier. According to this 'soft determinism', as William James called it, determinism is supposed to express a true doctrine in one sense of the words, and a false doctrine in another. Plenty of philosophers have argued that the problem about free will arises from what Hobbes called the 'inconstancy' of language. The same word, they say, is inconstant -- it can have several meanings. Even philosophers who argue for a simple determinism have to show that in their arguments the word 'free' is used with a constant sense, leading up to the conclusion that we are not free.

— Ian Hacking (1975) Why Does Language Matter to Philosophy? (p. 4-5) - ^ "We are free ..."

Berlin did not assert that determinism was untrue, but rather that to accept it required a radical transformation of the language and concepts we use to think about human life -- especially a rejection of the idea of individual moral responsibility. To praise or blame individuals, to hold them responsible, is to assume that they have some control over their actions, and could have chosen differently. If individuals are wholly determined by unalterable forces, it makes no more sense to praise or blame them for their actions than it would to blame someone for being ill, or praise someone for obeying the laws of gravity. Indeed, Berlin suggested that acceptance of determinism -- that is, the complete abandonment of the concept of human free will -- would lead to the collapse of all meaningful rational activity as we know it.

— "Isaiah Berlin," on: "Free Will and Determinism," in: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - ^ "The trees in the garden must be there ..."

Local realism is the combination of the principle of locality with the "realistic" assumption that all objects must objectively have pre-existing values for any possible measurement before these measurements are made. Einstein liked to say that the moon is "out there" even when no one is observing it.

- ^ See the cognitive map, concept map, entity-relationship model, mental model, mind map, semantic web, topic map, among many others that started flooding suddenly from 1975 on.

- ^ "Thus we can freely organize or map our thoughts upon this stable background."

In the previous excerpt on local realism, rephrase "value" into "form," "measurement" into "thought," and "made" into "mapped." Note that local realism underlies Einstein's determinism and hidden variable theory opposing to quantum indeterminism and Copenhagen interpretation as embraced by Niels Bohr and mainstream quantum physicists. Bohmian quantum mechanics attempts to preserve determinism in virtue of nonlocality but at the cost of locality, although Bell's inequality complicates the view. Ted Honderich at UCL argues against quantum indeterminism as too detached to be relevant to our life. A synoptic version or vision of positivism was strongly desired to escape from the reductionistic logical positivism as well as skepticism. - ^ See also:

"The world is my representation" is, like the axioms of Euclid, a proposition which everyone must recognize as true as soon as he understands it, although it is not a proposition that everyone understands as soon as he hears it. To have brought this proposition to consciousness and to have connected it with the problem of the relation of the ideal to the real, in other words, of the world in the head to the world outside of the head, constitutes, together with the problem of moral freedom, the distinctive character of the moderns.

— Arthur Schopenhauer (1818). The World as Will and Representation, Part I - ^ Stephen E. Robertson (1975 at UCL) "Explicit and implicit variables in information retrieval systems," Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 26(4): 214-22.

- ^ Mary Douglas (1975 at UCL) Implict Meanings: Essays in Anthropology

- ^ Paul Grice (1975 at UC Berkeley) Implicature

- ^ John Searle (1975 at UC Berkeley) Indirect speech act

- ^ David Bohm (1980 at Birkbeck College) Implicate and Explicate Order

- ^ Susan Dumais, et al (1988 at Bellcore) Latent semantic analysis [1] [2]

- ^ Ron Sun (c.1992). CLARION (cognitive architecture)

- ^ 5.2 The Theory of Ogden and Richards

- ^ When we communicate our thoughts about things, we use signs. That is to say, three factors - a thought, a thing, and a sign - are essentially involved in any communication event, either speaking or listening.

- ^ Walker Percy (1975) "The Delta Factor" (in) The Message in the Bottle

- ^ This original triangle of reference is marginally different from my own which reads:

Thought or REFERENCE SYMBOL REFERENT or Sign or Thing. - ^ Peter P. Chen (1976) "The Entity-Relationship Model: Toward a Unified View of Data," ACM Transactions on Database Systems, 1(1): 9-36.

- ^ Ogden and Richards (1923) also called their theory the "contextual theory of reference" or "causal theory of reference" from which the current use differs.

- ^ Contextual theory of reference:

McGinn's aim is two-fold: to undermine both descriptive and causal theories of reference, and to argue for his preferred, 'contextual' theory of reference. McGinn is moved to this position by emphasizing indexicals -- which he takes to be the primary referential devices -- rather than proper names. Linguistic reference, for McGinn, is a conventional activity governed by rules that prescribe the spatio-temporal conditions of correct use; the semantic referent of a speaker's term is given by combining its linguistic meaning with the spatio-temporal context in which the speaker is located. McGinn concludes his defense of this theory by demonstrating the plausibility of its implications for such topics as abstract objects, self-reference, attribution, the language of thought hypothesis, truth, and the reducibility of reference.

— Colin McGinn (2002) "The Mechanism of Reference" (in) Knowledge and Reality, pp. 197-223. (Abstract) - ^ Context in context

Context is a term that has come into more and more frequent use in the last thirty or forty years in a number of disciplines--among them, anthropology, archaeology, art history, geography, intellectual history, law, linguistics, literary criticism, philosophy, politics, psychology, sociology, and theology. A trawl through the on-line catalogue of the Cambridge University Library in 1999 produced references to 1,453 books published since 1978 with the word context in the title (and 377 more with contexts in the plural). There have been good reasons for this development. The attempt to place ideas, utterances, texts, and other artifacts "in context" has led to many insights.

— Peter Burke (2002) "Context in Context." Common Knowledge, 8(1): 152-177.