User:Jw1244/sandbox

The Mazahuas are an indigenous people of Mexico, primarily inhabiting the northwestern portion of the State of Mexico and small parts of Michoacán and Querétaro. The largest concentration of Mazahua is found in the municipalities of San Felipe del Progreso and San José del Rincón of the State of Mexico. There is also a significant presence in Federal District, Toluca and the Guadalajara area owing to recent migration. According to the 2010 Mexican census, there are 116,240 speakers of the language in the State of Mexico, accounting for 53% of all indigenous language speakers in the state.

Culture

[edit]Despite their proximity to Mexico City, Mazahua culture is relatively unknown to most Mexicans and even to many anthropologists.[1]

Mazahua women

[edit]One way that the Mazahuas have maintained their culture is through women’s dress, the elements of which have concrete meanings and specific values. The garments include a blouse, a skirt called a chincuete, an underskirt, apron, rebozo, quezquémetl and a sash.[1] The layering of clothing, especially the skirts, gives the women a robust look.[2] The traditional women’s outfit, especially the version handwoven in wool, is in danger of disappearing although there are efforts to save the skills and traditions needed to keep it.[1]

The chincuete is a highly pleated skirt, usually made with satin and lace. It has mostly replaced the older lía, which was two lengths of fabric sewn together horizontally with an embroidered edge. This garment is intricately folded and worn around the waist. Those who wear the chincuete also wear an underskirt, which has an embroidered edge that appears out from under the chincuete. The upper body is covered with a saco, or blouse with embroidery, layered with a quechquemetl and/or rebozo.[1]

The skirts are held in place with a woven sash, whose designs are culturally significant. The sash is one of the most important elements, worn around the waist which is considered to be the energy center related to the cosmos and Mother Earth. These sashes are woven with varied designs meant to convey ideas, stories, feelings and experiences. For example, an abundance of birds generally indicates beauty, freedom and grace. However, if a bird is portrayed with a thorn in its leg, it can mean some kind of physical or spiritual pain. Another important symbol is a stylized star, which symbolizes the guardian of the night which brings messages and is a protector of health.[1]

In the Mazahua region, almost all women ear crescent earrings as it is custom for a groom to buy a pair of these for his fiancé instead of a ring. These earrings are made from silver coins provided by the groom and made by traditional silversmiths. In the 1970s, efforts were made headed by María Teresa Pomar to preserve this silversmithing tradition, which was in danger of dying out. The efforts eventually led to the creation of a Mazahua silversmith guild whose members have won prizes for their work.[1]

Mazahua childhood

[edit]When given the opportunity to work or play, children often choose to work to contribute to their community. For example, a little girl may walk around the room doing as she pleased but without hesitancy help her mother whenever she needed help [3]. Without being explicitly told, Mazhua children often realize the value that activities such as weaving and selling goods has to the community, so they have an inherent desire to participate and learn how to perform these tasks themselves at an early age [4]. The work is understood as a necessary practice not only to maintain the household, but to be a part of the community. A deep desire to be useful to the family can serve as motivation to willingly contribute to chores. It is not uncommon for children to enjoy doing such chores, in fact they are often eager to do so. Children’s participation in daily family activities allow them to be directly involved with the family and community social life.

Language

[edit]

The Mazahua call themselves Tetjo ñaa jñatjo which roughly means “those who speak their own language.” The word Mazahua probably comes from Nahuatl meaning “deer-foot” referring to those who track deer for hunting. However, deer hunting has long since died out as a tradition with the loss of deer habitat.[5] Another interpretation of the name is from the name of the first chief of the people called Mazatlí-Tecutli.[6]

The Mazahua language belongs to the Oto-Pamean languages branch of the Oto-Manguean languages family, related to Otomi, Pame, Matlatzinca and others.[6][5] Despite efforts to preserve the language and culture, the percentage of children learning Mazahua as their first language is decreasing.[7]

According to the 2010 Mexican census, there are 116,240 speakers of the language in the State of Mexico, accounting for 53% of all indigenous language speakers in the state, most of whom are bilingual in Spanish.[8][9] Due to migration, the Mazahua language is now the sixth most commonly spoken language in Mexico City.[9]

Rituals and celebrations

[edit]Religious belief and cosmology is a blending of Catholic and indigenous beliefs.[6] Annual festivals are based on the Catholic calendar with each community having a patron saint, the most common of which is Isidore the Laborer. Two of the largest festivals are Feast of the Cross (May 3) and Day of the Dead (November 2). Traditional dances performed on special occasions include Danza de Pastoras, Danza de Santiagueros and Danza de Concheros.[6]

Day of the Dead is the welcoming back of the souls of the ancestors which are given offerings of foods they preferred in life along with drinks such as pulque and beer, along with bread, sweets and fruit. The altars are decorated much the way most others in Mexico are, with flowers, paper cutouts, etc., but they often also contain cloths hand embroidered with Mazahua motifs.[2]The Mazahua believe that the souls of the departed return on Day of the Dead in the form of monarch butterflies to enjoy the offerings of fruit and bread left and altars. To welcome them, they have a procession from the church to the cemetery and to bid them goodbye they have a procession in the opposite direction.[10]

The New Fire ceremony occurs on March 19, which is a blessing of fire in springtime, coordinated by the head of the Mazahua people. The ceremony is done in a circle with points aligned with the cardinal directions each honoring a different deity. Wood in the center is blessed and lit. The fire is then distributed through the use of candles.[2]

The Ofrenda al Agua, or Offering to Water, occurs on either August 15 or 16 at locations near rivers and lakes. The purpose of the event is to thank the element for its help in the agricultural cycle and to ask forgiveness for abuses to the resource. It takes place at the end of the rainy season when rains and water supply begin to diminish.[2]

One important local Mazahua ceremony is called the Xita Corpus, held in Temascalcingo. It honors and reinterprets an ancient myth of the “xita” (old ones) who come to the town after journeying. According to the myth they ask for food but there is none and the townspeople ask them to pray for rain, which they do. The rains come and the harvest is plentiful. Today the ceremony is done in conjunction with Corpus Christi, at the time when corn in planted, just before the rainy season. The ceremony has retained its significance although the growing of corn is no longer the area’s main source of income. One main aspect is the elaborate costume worn by the dancers who play the old travelers. It is meant to imitate traditional indigenous travelers and can weigh up to 55 pounds.[1]

The Centro Ceremonial Mazahua (Mazahua Ceremonial Center) is located in a small village called Santa Ana Nichi surrouned by forest, 32km from San Felipe del Progreso. It was created in the 1980s and is dedicated to preserving the Mazahua culture, history and handcrafts. The site contains three buildings which resemble kiosks, which are used for ceremonies such as the spring equinox as well as assemblies. It also contains a museum housing a collection of handcrafts and other objects to demonstrate the Mazahua life and worldview.[11]

Handcrafts

[edit]

The main handcraft producing areas are San Felipe del Progreso, Temascalcingo, Ixtlahuaca and Atlacomulco. Handcrafts include textiles such as blankets, sashes, rugs, cushions, tablecloths, carrying bags and quezquémetls made of wool. In San Felipe del Progreso and Villa Victoria, there are workshops which made brooms and brushes. In Temascalcingo, red clay pottery is dominant especially cooking pots, flowerpots and crucibles. The making of gloves, scarves and sweaters is dominant in Ixtlahuaca. Straw hats are made in Atlacomulco. Silversmithing is done in San Felipe del Progreso.[6]

Mazahua textiles attest to how they live, how they view their world and how they represent the symbols of their culture. Weaving and embroidering of times begin with buying fabric and thread in cities such as Toluca and Zitácuaro. There are set rules as to how to arrange designs and colors. Textiles are made for personal use as well as for sale and include tablecloths, blankets, cushions, carrying bags and more. Textiles are also made as offerings covering altars and walls at special ceremonies such as saints’ days.[1]

In 2011, a group of rag dolls made by Mazahua women were displayed at the Museo de Arte Popular. The dolls were traditional but they were dressed in the manner of famous international designers. The event was called Fashion’s Night Out, sponsored by Vogue México .[12]

While traditional handcrafts have been an important part of Mazahua culture, the tradition of making them is becoming lost with the younger generations.[13]

Other aspects

[edit]Health for the Mazahuas is both physical and spiritual. They also believe in “good” and “bad” ailments, the first sent by God and the others provoked by some evil on someone’s part or supernatural causes. “Good” ailments include diarrhea, pneumonia, bronchitis and intestinal parasites. “Bad” ones are classed as “the evil eye,” “fright” and “bad air” among others. The classification indicates the kind of treatment which can include herbal remedies, massages, ceremonies and in other cases, professional medicine.[6]

The nuclear family is the base of Mazahua society, with defined roles determined mostly by sex and age. In addition to familial duties, Mazahuas are required to contribute voluntary labor to the community, called faena. This work often includes the building of institutions such as schools, markets and roads.[6] Similar to work performed as a child, faena work is seen not as a chore, but as prosocial behavior centered on the community.

Mazahua cuisine is often tied to ritual and its cosmology and very similar to Otomi cuisine. Common ingredients include squash, pipian sauce, a vegetable called quelite and a wide variety of mushrooms, generally found in the forest at certain times of the year.[14] Common feast foods are turkey in mole sauce and drinks called zende and pulque, especially on the locality’s patron saint’s feast day. Turkey in mole sauce is usually reserved for the patron saint day and weddings. Zende is a local drink made with sprouted corn, which is brewed and colored with a little bit of chili pepper. A small amount of pulque is then added to start the fermentation process. Ready about four days later, it has a sweet and sour taste.[14]

History

[edit]The origin of the people is not certain. One story says that they were one of the five Chichimeca groups that migrated to the area in the 13th century, headed by a chief named Mazahuatl. Another story indicates that they are descended from the Acolhuas.[6] The Mazahua lived for hundreds of years in the forests of northern State of Mexico into Michoacán, mostly by hunting and gathering. Clothing was originally woven from maguey fiber, which is still used for items such as bags and belts. The fiber was dyed with pigments from vegetable and mineral sources.[5] With the rise of the Aztec Empire, Mazahua territory was subdued by Axayacatl and later the Mazahuas participated in further Aztec conquests to the south.[6]

During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, the area was taken over by Gonzalo de Sandoval. The Franciscans were tasked with evangelization, with a group of Jesuits in Almoloya de Juárez. During the colonial period the territory became economically dominated by large haciendas in Temascalcingo, El Oro, Jocotitlán and Almoloya de Juárez. Later in Mexico’s history the Mazahuas supported the Mexican War of Independence and the Mexican Revolution .[6]

Since the colonial period to the present day, the Mazahuas have kept much of their culture and traditions, but there have also been significant changes.[1] The two main aspects that they have maintained are the Mazahua language and the women’s distinctive dress.[5] The culture developed to live in temperate to cold climate, in an area filled with pine, holm oak and oyamel fir trees. Since the latter 20th century, these forests have been decimated by logging, erosion and topsoil loss.[15] Men traditionally earned money for the family through agriculture and making charcoal. In the past Mazahua communities were self-sufficient but this is no longer the case.[5] The economy of most Mazahua families has been shifting away from agriculture to integration into the wider Mexican economy.[1] One major example of this is the employment of Mazahuas at a former ranch called Pastejé near Atlacomulco, which is now known for its electrical appliance factory. The plant began employing Mazahuas, primarily women, to do assembly work to produce electricity and water meters, conductors, bulb holders and more. In December 1964, another plant opened and hired about 700 young women. The work at the factory had significant effects on the culture. One change was the ditching of a petticoat garment Mazahua women wore for warmth as it kept sweeping along the factory floor, as well as the fact that the young women wanted to be more like city women.[1] This has also led to other changes in lifestyles such as houses of cinderblock and cement instead of adobe.[6]

Another major change for the Mazahua people has been migration to other areas of Mexico and even the United States, either seasonally or permanently. Work in the cities is easier and pays better than traditional agriculture.[1] This began in 1945, when the Atlacomulco-Toluca highway was built, making it easy to travel out of the area, primarily to Toluca and Mexico City. Men began to migrate to Mexico City, generally to do construction. They brought their wives who began to sell fruits, vegetables and later rag dolls in the street, often making more money than their husbands. They were so successful at selling that other vendors began imitating their distinctive dress.[1] Mazahua women in their traditional garb began to be called “marías” for unknown reasons. This is the basis of a famous television character from the 1970s called La India María, who wore a costume similar to Mazahua women. However the only similarity between La India María and Mazahua women is the costume.[1] Many Mazahua families have moved to the Guadalajara area, mostly settling in the municipality of Zapopan.[9]

While most Mazahuas have left their traditional territory for economic reasons, some have also left because they had converted to Protestantism, especially to the Jehovah’s witness faith.[9] The mass migration has left a number of Mazahua communities, such as San Felipe Santiago, mostly populated by women and children. The men return only for certain important festivals such as the one for the town’s patron saint.[1]

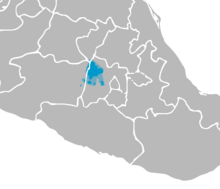

Territory

[edit]Mazahua territory is located in central Mexico, northwest of Mexico City. It extends over 6,068 km2 centered on northern and western State of Mexico, extending into small parts of Michoacán and Querétaro.[15][1] In the State of Mexico, they are found in the municipalities of Almoloya de Juárez, Atlacomulco, Donato Guerra, El Oro de Hidalgo, Ixtlahuaca, Jocotitlán, San Felipe del Progreso, Temascalcingo, Villa de Allende and Villa Victoria.[6][7]In Michoacan they can be found in the municipality of Zitácuaro and Susupuato .[9][6] This territory is bordered by that of the Otomi to the north and east, the Matlatzincas to the south and by the Purépecha to the west.[15] The Mazahua are the largest indigenous group in the State of Mexico, most dominant in the municipalities of San Felipe del Progreso, San José del Rincón, Villa Victora and Villa de Allende.[7]

The territory is mountainous consisting of small mountain ranges which are part of either the Sierra Madre Occidental or the result of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. These ranges include the San Andrés which runs through Jocotitlán, San Felipe del Progreso, Atlacomulco, and El Oro. The climate is temperate to cold because of the altitude. Flat areas in the region are important for agriculture. The main drainage is the Lerma River along with the La Gavia, Las Lajas, Malacotepec and La Ciénega Rivers.[6][7] Because of the proximity of this area to Mexico City, it has good road infrastructure. There are also a number of important dams such as Villa Victoria, Browkman, El Salto and Tepetitlán. Most of the territory is forest with some semi desert areas but both are seriously degraded. Both logging and hunting have put a number of species in danger of extinction.[6] Part of Mazahua territory is in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve.[15]

Socioeconomics

[edit]About forty percent of the population works in agriculture producing corn, beans, wheat, barley, oats and potatoes, with peas, vegetables and flowers grown in some municipalities. Most production is for auto consumption. Most agriculture is done on ejido land working in families using traditions methods and tools. Livestock mostly consists of sheep and cows with some fish farming done. Forest products include wood, firewood and charcoal.[6] Another traditional source of income, especially in San Felipe del Progreso is handcrafts, making blankets, sashes, rugs, carrying bags, tablecloths, quexquemitls, vests and other garments from wool. Other common crafts include making carrying bags from recycled plastic strips, brushes and brooms and pottery.[13] Most of the municipalities in Mazahua territory have a high degree of socioeconomic marginalization. Two, El Oro and Jocotitlán, are considered to have a medium level and another two, Atlacomulco and Valle de Bravo have a low level.[7]

Many Mazahua men and women migrate temporarily or permanently to the cities of Toluca and Mexico City to obtain work as agriculture is generally not sufficient to meet needs. Some Mazahuas migrate as far as Veracruz, Sonora, Querétaro and Jalisco. Men generally work in construction and commerce and women usually work in domestic service or in commerce.[6][7]

Mazahua communities generally are near Otomi ones, with whom they maintain mostly economic ties, exchanging products from their respective regions. Mazahua relations with the mestizo population is complicated but generally socially inferior with the mestizos having most of the social and economic power.[6] Education levels are low because of social and economic factors, with most only finishing primary school.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Textiles Mazahuas (in Spanish/English). Vol. 102. Mexico City: Artes de México. 2005. pp. (2)-(16). ISBN 978 607 461 076 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c d "Fiestas Mazahuas" (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Paradise, Ruth (1985). "Un analisis psicosocial de la motivacion y participacion emocional en un caso de aprendizaje individual". Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos. 15 (1): 83–93.

- ^ Paradise, Ruth. (2005). Motivación e iniciativa en el aprendizaje informal. Sinéctica, 26, 12-21.

- ^ a b c d e Cárdenas Martínez, Celestino (2000). Cantos, cuento y mitos mazahuas de San Pedro El Alto, Temascalcingo (in Spanish). Toluca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. pp. 20–21. ISBN 968 835 498 8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Mazahuas" (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. October 22, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mazahuas" (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Mexico. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ "Datos Estadísticos Estado de Mexico" (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Mexico. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Jorge Alberto Mendoza (October 3, 2010). "Mazahuas, los sin tierra en Zapopan". Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mazahua Offering to the Dead set at the National Museum of Anthropology MNA" (Press release). INAH. November 1, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ "Centro Ceremonial Mazahua" (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Gerardo León (September 10, 2011). "Muñecas mazahuas muy fashion". El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Tradiciones del Pueblo Mazahua" (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Olivia Tirado (September 1, 2012). "Gastronomía mazahua todo un ritual". Voz de Michoacán (in Spanish). Morelia. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Sánchez Núñez, Edmundo (July–Dec 2006). "Conocimiento tradicional mazahua de la herpetofauna: un estudio etnozoológico en la Reserva de la Biósfera Mariposa Monarca, México". Estud. soc (in Spanish). 14 (28). ISSN 0188-4557. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

External links

[edit]- Ethnologue report on Michoacan Mazahua

- Ethnologue Report on Central Mazahua

- Mazahuan handicrafts

- Mazahuan women in defense of Human Rights

- The state of Mexico on the Mazahua

Category:Ethnic groups in Mexico Category:Indigenous peoples in Mexico