User:JosephMEP/sandbox

Théophane Vénard | |

|---|---|

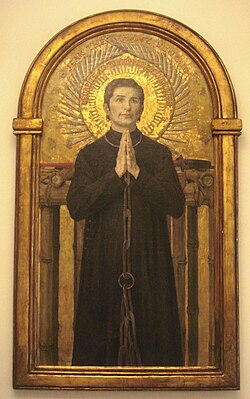

Painting of Théophane Vénard in chains, at the Paris Foreign Missions Society. | |

| Saint and Martyr of Vietnam | |

| Born | November 21, 1829 Saint-Loup-sur-Thouet, Diocese of Poitiers, France |

| Died | February 2, 1861 (aged 31) Tonkin, Vietnam |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | May 2, 1909, Rome, Kingdom of Italy by Pope Pius X |

| Canonized | June 19, 1988, Vatican City, Rome, Italy by John-Paul II |

| Major shrine | Crypt of the Paris Foreign Missions Society |

| Feast | November 24 |

Théophane or Jean-Théophane Vénard, born November 21, 1829 at Saint-Loup-sur-Thouet and martyred February 2, 1861 in Hanoi, was a priest of the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Missionary to Tonkin, he was condemned to death and executed. He was then declared blessed, and later canonized, by the Catholic Church.

After his studies, he entered the seminary and decided to become a missionary-priest under the auspices of the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Ordained a priest in 1852, he was sent to China as a missionary. After a long voyage of more than seven months, he arrived at Hong Kong, the door of entry into China. After having heard his assignment, he was finally nominated to Tonkin, the northern part of current-day Vietnam.

Entering clandestinely into Tonkin in 1854, he learned the Vietnamese language and placed himself at the service of the local bishop. The situation was very difficult for Christians and the persecutions were very intense against them. He took refuge in caves and hide-outs, protected by the Christian villagers. There he translated various epistles and was named superior of the seminary. In 1860, he was denounced by a villager and captured, then executed the following year by decapitation.

The numerous letters which he wrote all throughout his life, and notably during his missionary period, were collected and published by his brother Eusèbe after his death. They made a notable impression in France. Thérèse de Lisieux who is considered a saint which resembled him, affirmed upon reading his letters, "These are my thoughts, my soul looks like his soul," meanwhile contributing to make him, for Catholics, one of the most renowned martyrs of the 19th century. Numerous similarities exist between the spiritualities of Théophane Vénard and that of Thérèse de Lisieux, as much in the search for spiritual smallness as in the grand vision for mission.

The process of Théophane Vénard's beatification was opened shortly after his death. He was beatified in 1909, then canonized in 1988 by Pope John Paul II.

Biography

[edit]Childhood and secondary studies

[edit]

Théophane Vénard was born on 21 November 1829 at Saint-Loup-sur-Thouet. Son of a very devout schoolteacher who had him baptised as Jean-Théophane, he was the second of four children: he had an elder sister, Mélanie, and two younger brothers, Eusèbe and Henri[1]. He manifested his desire to become a missionary and a martyr at the age of 9: "Me too, I want to go to Tonkin, me too, I want to be a martyr", saying this upon reading the martyrdom of Jean-Charles Cornay in the periodical, Annals of the Propagation of the Faith which described the life of missionaries in Asia[2]. This desire did not manifest itself again during the 10 years that followed[2].

He pursued his studies his studies 50 kilometers from his village, at the college of Doué-la-Fontaine where he became a boarder in 1841[3]. The distance from his family was difficult for the child, who spoke of it as "exile". Nevertheless, he described in his letters to his sister Mélanie his religious activities: the recitation of the Rosary, the donations which he made for the work of the Propagation of the Faith. He was a good student, but his teachers noticed his uneven mood, with some signs of irascibility[4].

He learned that he was able to make his First Communion on Thursday, 28 April 1843 and he wrote to his parents that he was making efforts in order to obtain some awards of excellence[5]. At the beginning of the year 1843, he learned of the death of his mother, of poor health[5]. This event marked the beginning of a very profound relationship with his sister Mélanie[5]. His little brother Henri became in his turn a boarder at Doué, but Théophane was very disappointed by his lack of piety. On account of financial difficulties encountered by the family, his father asked him not to return to the family home at vacation time in order to save money[6].

On 14 February 1847, Théophane, at the age of 18, expressed some doubts about his vocation. He traversed a crisis, which in many ways resembled a crisis in the face of the greatness with which he conceived of the vocation: "For some time, there has been something bothering me: I am coming near to the end of my courses, and I still don't know my vocation. This torments me. However, I feel well called to the clerical state; I tell myself, 'Oh! How beautiful it is to be a priest! Oh! How beautiful it is to say a first Mass! But one must be pure, more pure, sort of, than the angels! So, I'm still in doubt."[7]. Despite his doubts, he pursued his studies at the seminary.

Seminary education

[edit]Minor seminary of Montmorillon and major seminary

[edit]

Théophane Vénard entered the minor seminary of Montmorillon. He was happy, and a good student as before, but he revolted against the lack of liberty and autonomy which reigned in the discipline of the minor seminary: "Almost seven years that I have wiped the dust of the colleges!... I am no longer a child, I want to taste the life of a man, breathe alone in a room and not in a study, amid the deafening noise of feet and desks, of the comings-and-goings. It is there to suffer martyrdom... In order to be content in this state, one must have a vocation, and I don't have the 'vocation of the college'" Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 23. He wrote long letters to his brother Eusèbe, who also wanted to become a priest, and found himself working at the theater as a comic[8].

In 1848, he finally entered the major seminary of Poitiers. He wore the cassock, benefited from a private room and appeared very happy, as he wrote to his sister: "It's heaven on earth. How happy are we in the house of the Lord[9]! Théophane was passionate about his studies: he learned Ancient Greek and Hebrew, earned excellent grades, and his behavior didn't show any signs of irregularity or irascibility as at college[10].

During this time, he mentioned more and more frequently some missionaries or seminarians of the Paris Foreign Missions Society in his correspondence with his family[11]. This discreet interest in the Paris Foreign Missions Society was a way for Théophane to prepare his family for his entrance into that society, in an era where the missionary vocation was very difficult and perilous, between the voyages on boat and the persecutions against Christians. The desire to enter the Paris Foreign Missions Society was then a difficult decision for his family to accept. During the break of 1850, he returned close to his family and privately forewarned his sister Mélanie of his intentions, making her guard the secret[12]. On 21 December 1850, he was ordained a subdeacon and obtained permission from his bishop, Mgr. Pie, to leave the diocese of Poitiers in order to go to the seminary of the Paris Foreign Missions Society[13]. It was no later than 7 February 1851 that he wrote a long letter to his father in order to ask his blessing upon his missionary vocation[14].

Seminary of the Paris Foreign Missions Society

[edit]Théophane Vénard entered the seminary of the Paris Foreign Missions Society on 3 March 1851, under the direction of Father François Albrand, and on this occasion took the train for the first time[15]. He wrote to his sister on March 7 in order to tell of his wonderment at his family, and to send a photograph upon their request[16]. He befriended Joseph Theurel, his future bishop, and Dallet, future missionary in India: all three shared a common quest for perfection. He took interest in modernity, and took passion in physics, natural history and geography, but had a harsh view of the romanticism which was then in vogue, which he found absurd[17]. Meanwhile, he wrote numerous letters to his family and friends and developed a veritable talent for lettercraft.

During this time, the situation in Paris grew tense, following the 1851 French coup d'état; the first barricades appeared on the fourth of December. He reassured his relatives and showed a vision for society in one of his letters: "If there were danger, it would be dangerous for the whole world, above all for rich, bad Christians; because the working class has been demoralised by them: they no longer believe in God and they want to please themselves on Earth; and, because they don't possess anything, they revolt against those who possess[18]. At the referendum of 20 December 1851, he did his civic duty by voting, even if he wasn't certain of the benefit of his vote: "I wrote, yes, on my ballot without knowing too well whether I did bad or good. Eh, who knows? I pray God does not render an account of my civic action, the first and perhaps the last[19].

At the heart of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, he showed himself to be quite active and rapidly accumulated the roles of organist, sacristan and sweeper-in-chief[18]. He was ordained a deacon on 20 September 1851[19]. The need for missionaries accelerated things: he asked from his bishop a dispensation for an early priestly ordination in order that he could depart for China, a dispensation to which the Bishop agreed[19]. He was ordained a priest on Saturday, 5 June 1852 by Mgr. Marie Dominique Auguste Sibour at Notre-Dame de Paris[20]. He fell gravely ill for close to three weeks, without a doubt with the Typhoid fever, and recovered[21].

The following September 13, the news was official: he was sent on mission to China. Even though he showed himself to be very happy, he would have preferred Tonkin, the place of martyrdom of Jean-Charles Cornay whom he held in particular veneration[22]. The ceremony of departure took place September 16 at the oratory of the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

Voyages and stopovers

[edit]Voyage to Asia

[edit]On 16 September 1852, Théophane Vénard left for Antwerp with four missionaries of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, among them Lavigne and Joseph Theurel. Their ship, the Philotaxe, left Antwerp on September 23, but it had to make a stop at Plymouth on account of some damage caused by a storm in the North Sea[23]. He wrote regularly to his family to describe his journey to them. He passed by the Cape of Good Hope, and arrived in Madagascar for Christmas[24]. The boat then took the direction of the Sunda Strait, in the Dutch East Indies. This was when the missionaries first encountered tropical heat, and had their first encounters with some Asians during a stop at Java[25]. They arrived at Singapore after a voyage of close to five months[23].

At Singapore, the missionaries separated: two of them took the route to Cambodia, while Théophane Vénard, Theurel and Lavigne set off for China[26]. They embarked on a new ship, the 'Alice-Maud, then entered Hong Kong on a junk after a rather difficult crossing[26]. They arrived on 19 March 1853, after more than seven months on the sea[23].

Hong Kong

[edit]At Hong Kong, Théophane Vénard awaited his assignment in China[23]. He was saddened to not have received any letter, but he set himself to the study of the Chinese language. The study of the language was very difficult for him, as he wrote, "I would be tempted to believe that this language and its characters had been invented by the Devil in order to render its study more difficult for the missionaries!"[23]. He also had to endure the oppressive heat of Hong Kong, which deteriorated his health[27]. He was waiting in Hong Kong still when his friend Theurel arrived in western Tonkin. Théophane indicated to his superiors in the Paris Foreign Missions Society his desire to depart on mission, even though his mission in China had been suspended for reasons of prudence[28]. Lavigne, the other travelling companion of Théophane Vénard, returned finally to France on account of health problems[29]. Théophane entertained also a correspondence with his friend Dallet, missionary in India, whom he told of his discouragement[29].

After more than fourteen months of waiting, a new order arrived from the Paris Foreign Missions Society: depart for Tonkin[30]. Théophane wrote to his family and friends his joy to be departing for Tonkin, and to his friend Dallet his joy to be departing for the land of the martyrs: "Oh! Dear Father Dallet, everytime that the thought of martyrdom presents itself to me, it thrills me; it's the good and beautiful part which is not given to all..."[30].

On 26 May 1854, he embarked with a friend, Legrand de La Liraÿe, on a Chinese smuggler's junk and headed into Tonkin by means of Hạ Long Bay[31] · [32]. The day of his departure for Tonkin, he learned that Jean-Louis Bonnard, a member of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, had been executed by decapitation in Nam Định Province, one year after the death of Augustin Schoeffler[31].

Missionary

[edit]Clandestine entry

[edit]

The voyage of Théophane Vénard to Tonkin was made clandestinely: he and his companion Legrand de La Liraÿe hid themselves from the time of their departure onwards, in order to avoid inspection in a country where the Christians were being actively persecuted[33]. The edict of the emperor of Viêt Nam Tự Đức condemned the entry of all priests into Tonkin: "The European priests shall be thrown into the depths of the sea or the rivers; the native priests, whether or not they trample the cross underfoot, will be sliced through the middle of their body, in order that all may know the severity of the law"[34]. The emperor seemed to exemplify the same political strategy as his grandfather Minh Mạng, that is to say, excessive persecution resulting in the death sentence of any one who calls himself a Christian[31].

Théophane Vénard and Legrand de La Liraÿe disembarked 23 June 1854 and rested a few days, before clandestinely traversing the region with the aid of some Cochinchinese guides in order to report to their missions in Western Tonkin. When they crossed through villages, they hid in curtained palanquins in order to not be unmasked[35]. They reached the Hong River and they went up to Vinh Tri where they presented themselves to the bishop on 13 July 1854[36].

Mission in Tonkin

[edit]

Upon his arrival, a surprise awaited the young missionary: the bishop Pierre-André Retord prepared, with fitting ceremoniousness, the ordination of 26 clerics, the ceremony taking place in the presence of the official army[37]. Indeed, even though the emperor had adopted a harsh anti-Christian politique, the situation was different in western Tonkin[37], of which the Viceroy, Hung de Nam-Dinh, step-father of the emperor, had been cured of a malady of the eyes by the priest Paul Bao-Tinh. It was he who requested that the Christians under his authority not be bothered. The Viceroy bound himself by this promise, and Christians were not persecuted in western Tonkin where the emperor's edict was not enforced. Promoted to seminary rector, Paul Bao-Tinh benefitted from this liberty by having public liturgical celebrations, meanwhile in the neighboring regions the situation was very difficult for Christians[38] · [31].

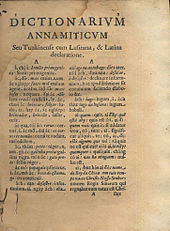

Théophane Vénard integrated quickly with the Cochinchinese, especially as he arrived with a harmonium which enchanted the bishop: who named him director of music[38]. In contrast to his struggle with the Chinese language, he learned Vietnamese with great facility, especially thanks to quốc ngữ, the romanization of the Vietnamese alphabet realised in the 17th century by Alexandre de Rhodes, one of the founders of the Paris Foreign Missions Society[39].

He very quickly gave his first sermon in Vietnamese. Theurel wrote of it, "It seems that pere Vénard will speak the language with a correct accent; his soft voice lends itself well to the rest. He feels himself to be very close to the Vietnamese, who treat him well. Already, he has accompanied bishop Pierre-André Retord in visiting Christians, and he will soon be able to help with the administration[40]". Even if the situation was very auspicious for the Christians in western Tonkin, Théophane nonetheless had to flee and hide himself on 1 November due to a visit from a mandarin of the emperor in the region[39]. These visits multiplied, and Théophane and his companions more and more had to go into hiding[39].

He fell gravely ill at the end of the year 1856[41]. He was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, a very grave diagnosis at that time[40] · [42]. He was thought to be dying, and on two occasions he was administered last rites[43]. In order to not be a burden to the mission, he agreed to be treated by a Vietnamese. His treatment was done by acupuncture and by moxibustion[40] · [44]. He was healed, as wrote the bishop Retord to the superior of the Paris Foreign Missions Society at Hong Kong: "The little père Vénard, that you always believe to be sick, seems to have been relieved from this honorable function: he is not strong, he is not robust, but he is no longer sick. It seems that by taking all he precautions which prudence necessitates, his health will sustain him[40]."

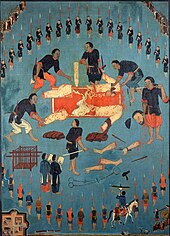

Persecutions against Christians

[edit]The emperor Tự Đức was astounded that not one missionary had been discovered and executed since Jean-Louis Bonnard in 1852[45]. He then decided then to send inspectors throughout the entire empire in 1857 to enforce the edict against Christians[45]. 27 February 1857, two among them discovered some Christians and arrested the priest Paul Tinh, rector of the seminary. The inspectors brought him before the Viceroy at Nam-Dinh. In order to remove from himself any accusation of appeasing the Christians, the Viceroy condemned him to death and decided to order the destruction of the seminary. He sent to his prefects an anti-Christian pamphlet in which in he summons the prefects of neighboring provinces to do the same, under pain of sanctions and report to the emperor[40] · [45]. This change of politics unleashed a very strong persecution against the Christians, the prefect of Hüng-Yen killing more than 1,000 among them[46].

The solders returned on March 1 1857, thus the missionaries had to flee onboard a sampan and go upstream. On that day, the seminary was entirely destroyed[47]. Vénard and Retord sought refuge among the mountains of limestone which border the delta. There they learned of Paul Tinh's death sentence[45]. The bishop Paul-André Retord decided to send Théophane Vénard to Hoang-Nguyen, to the south of Hanoi, close to Father Castex, provincial superior of the province of Hanoi where the persecutions were less prominent[45]. Upon arrival, he discovered Father Castex in agony: he died a few days later. Vénard then took over as his successor[45]. He continued to write to his sister, but with serenity and discretion, probably in order to not bother her; in contrast, his letters to Father Dallet descrive the cruelty of the persecution[48].

Clandestinity and flight

[edit]

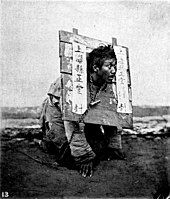

Théophane Vénard tried to nonetheless pursue his mission in total clandestinity. Thanks to the protection of the Tonkin Christians, he was able to rapidly free in case of danger and escape the persecutions. Nonetheless, a letter written by Father Vénard and his companion Father Theurel was intercepted by soldiers of the king in the belongings of a Chinese smuggler bound for Hong Kong[49]. The Viceroy thus learned of the existence of two missionaries, who he then set out to capture. Forewarned by some of the Christian faithful, Théophane once again took flight. Two Vietnamese catechists were captured and were forced to wear the cangue[50].

Having took refuge in the mountains, Mgr Retord ordered Théophane and Theurel to disappear completely in order to wait out the searches and avoid the zeal of the soldiers[51]. They then parted for Dông Chiêm, in the mountains, where some Christians resupplied them regularly[51]. They had to flee again after having encountered some Vietnamese who introduced themselves as tiger hunters. They took refuge in a village, hiding in basements excavated by Christian villagers for this very purpose[52].

In parallel with the persecutions, the attitude of France continued to aggravate the anti-Christian hostility: a French corvette presented itself numerous times, announcing the arrival of missionaries and requesting their protection[46]. The appearance of this ship irritated the Emperor, equally that in 1858 the squadron of the admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly, after the Bombardment of Tourane which led to the destruction of the Vietnamese fleet, berthed in the port of Tourane for several months[53]. Finally, the admiral decided to part for Saigon, which contributed to rendering the situation even more difficult for Christians, who were caught between the warring states of Vietnam and France[53].

Théophane Vénard lived under very harsh conditions of clandestinity: he moved from village to village, hidden in various caches, behind double walls, sometimes without at all seeing the light of day. In order to hide himself, he often benefitted from the aide of religious sisters, the Lovers of the Holy Cross, of which he became the spiritual father. The letters which he would come to write were written under very difficult living conditions: "You may ask us: 'How do you not go mad?' Always closed in the narrowness of four walls, under a roof which one can touch with one's own hands, having for guests spiders, rats, and toads, obliged to always speak in a low voice, assailed every day by bad news: priests taken, decapitated, Christian communities destroyed and dispersed amongst the pagans, many Christians who apostatize, and those who stand fast sent to the stifling mountains where they perish in abandonment, and all this without knowing when it will all end, or rather, with no end too much in sight, I confess that it requires a special grace to not submit to the temptation of discouragement and sadness[54] · [55]."

Bishop Paul-André Retord died 22 October 1858, taken by the favor[52]. Father Jeannet then took his place as vicar apostolic, and chose Joseph Theurel as successor. Father Theurel was ordained a bishop clandestinely March 6 1859[56]. The new bishop requested the missionaries to make a report concerning the missions. In his response, Théophane Vénard spoke to him of the difficulties of teaching catechists, attaching his translation of the epistles in Vietnamese. These recommendations drove Bishop Theurel to name him director of the seminary[57].

On January 15 1860, after having received authorization from Bishop Theurel, he consecrated himself to the Virgin Mary, following the prayer of Louis-Marie Grignion de Montfort. From this moment on, he signed his letters "MS" for Mariae Servus ("servant of Mary")[58].

He continued still to hide himself and decided to depart for another village, Ke-beo, where hid himself at an elderly lady's home. One of this villager's nephews visited her, and denounced the presence of Christians in her home[57]. On November 30 1860, the soldiers arrived and discovered him hidden in a double wall[40].

Detention and execution

[edit]

Captured, Théophane Vénard was taken to the palace of the viceroy in Hanoï, where he was put in chains and confined to a cage[59]. The viceroy came in person to interrogate him[54]. During the interrogation, the missionary made such a good impression on the viceroy that he demanded that the priest be afforded a larger cage, equipped with mosquito netting, and that he might be well-fed[54].

Whereas the authorities of Hanoï had sent their report to the emperor, Father Théophane had the right to leave his cage from time to time in order to take a walk outside, and to share a meagre repast with his guards. He had also the opportunity to write. Three clandestine Christians came to know him: a soldier, the cook who brought him the Eucharist every Friday, and a policeman, who secretly had a priest come to hear Théophane's final confession[60].

On January 20 1861, Théophane Vénard wrote farewell letters to his family.

While my sentence awaits, I wish to address to you a new adieu, which will probably be my final. The days of my imprisonment pass peaceably. All who surround me honor me, a good number love me. From the great mandarin to the last soldier, all regret that the law of the kingdom condemns me to death. I have not had to endure tortures, like many of my brothers. A light swoop of the saber will separate my head, like a spring flower that the master of the garden plucks for his pleasure. We are all flowers planted on this earth that God plucks in his time, a little sooner, a little later. One is the purple rose, another the virginal lily, another the humble violet. Let us all set out to give pleasure, according to the fragrance or the radiance that we are given, to the sovereign Lord and Master[54] · [61].

The morning of February 2nd, the prefect announced to him the sentence: death by decapitation. He was transported to the Hong River. At the riverbank, he undressed and knelt down with his hands tied behind his back[54]. The executioner, drunk at the time of the execution, tried five times to behead the condemned: the first blow of the saber only grazed his cheek, the second hit his throat and three more swipes were necessary to accomplish his execution[23].

The Christians interred his body, whereas his head was mounted to a pole for three days, then tossed in the river. A Christian policeman, Paul Moï, charged some fishermen with its recovery, and had them carry it to two bishops of which he knew their hiding place. They had it placed in a trunk before having it interred. Six months later, under cover of nightfall, some Christians exhumed the corpse and reburied it in the cemetery of the parish of Dông-Tri[62].

Spiritual heritage

[edit]Similarities with the spirituality of Thérèse de Lisieux

[edit]The spirituality that Théophane Vénard developed has numerous points in common with that of Thérèse of Lisieux, future doctor of the Church. Thérèse of Lisieux described her spirituality as being that of the "little way" or of the spiritual childhood. Even though she had already developed the essentials of her thought before having discovered the story of Théophane Vénard in November 1896, several elements demonstrate great similarities between their spiritualities. These resemblances are no doubt in part due to the veneration which Thérèse had for Théophane Vénard: After having read his writings, she exclaimed, "These are my thoughts, my soul resembles his[63]."

The two principal similarities between the spiritualities of Théophane Vénard and of Thérèse de Lisieux concern that which is described as the spiritual childhood, and their conception of mission. Spiritual childhood can be described as a spirituality of trust in God despite or even thanks to weakness and smallness, as a child before its father, leading to acceptance and to offer one's life for God. Their second point in common is their conception of mission. Mission and martyrdom were very linked then in the 19th century, notably at the seminary of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, of which numerous members were martyred at the hands of various persecutions in Asia. The missiology developed by Théophane Vénard resembled in numerous aspects that which Thérèse de Lisieux developed in her writings.

The foundations of the spirituality of the "Little Way"

[edit]Smallness

[edit]In his correspondence, Father Vénard described on numerous occasions his smallness and human weakness in the face of his vocation as a missionary. For him, the vocation of the priesthood demands numerous qualities: to be a priest one must be holy, as he affirms in one of his letters to his sister Mélanie. Yet, he considered himself as not being one of the best models of sanctity: "But, a reflection comes to me: all of that is good, without a doubt, but, in reality what is the priesthood? It is detachment from all the goods of the world, a total abandon of all temporal interests. To be a priest, one must be holy. In order to direct others, one must first of all know how to direct oneself[64] · [65]." Thérèse of Lisieux doubted in the same manner in the face of the grandeur of her vocation: "A storm arose in my soul unlike any I had seen before. Up until that point, not a sole doubt about my vocation had entered my mind, it was necessary that I had to endure that trial... My vocation appeared to me like a dream, a chimera, I found the life of Carmel very beautiful, but the demon inspired me with the assurance that it was not made for me, that I failed my superiors in advancing on a way that was not my own[66]…}}

Théophane used a floral metaphor to describe the place of each person: in a garden there is a multitude of flowers, certain ones grand, others small, but every person has a specific place: {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Thérèse developed the same floral metaphor to speak of the vocation of each person: {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Théophane affirmed to his sister that he wasn't the saint that she believed him to be. He was conscious of his limits, thus he wrote: {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Ces sentiments sont proches de ceux que Thérèse de Lisieux décrit dans Histoire d'une âme : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Ce sentiment d'indignité se traduit chez Théophane par une volonté d'humilité et de modestie. Ainsi, lors d'une de ses retraites au séminaire des Paris Foreign Missions Society, il écrit l'une de ses résolutions : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Cette recherche de la discrétion et de l'humilité conduit Théophane Vénard à signer ses lettres à son évêque {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Interior confidence in God

[edit]La petitesse décrite par Théophane le conduit à avoir confiance en Dieu malgré sa faiblesse. La petitesse et la faiblesse sont donc des atouts face aux difficultés. Dans la dernière année de sa vie, il est confronté aux persécutions contre les chrétiens et c’est dans la confiance intérieure en Dieu qu’il puise la force nécessaire pour ne pas se décourager : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) C’est cette même confiance intérieure en Dieu que Thérèse développe dans ses écrits : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Dieu est considéré comme celui qui peut tout, à qui on peut faire confiance. Dans ses dernières lettres, Théophane Vénard prend la métaphore du jardin afin de développer sa conception : il considère que toute personne est une fleur, et que Dieu est le jardinier. La grandeur de la fleur n’importe pas, et il faut laisser Dieu agir comme agit un jardinier ; dans sa lettre d’adieu à son père, il se décrit ainsi comme une fleur : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Il file la métaphore : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Ordinary life lived at the service of Love

[edit]

La confiance intérieure en Dieu se manifeste non seulement dans la vie intérieure, mais dans le fait de croire en l'action de Dieu à travers les événements de la vie. Théophane, comme Thérèse, croit en l'action de Dieu à travers l'obéissance. D'abord envoyé en Chine, il y voit la volonté de Dieu : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Cette conception traditionnelle dans la foi chrétienne, institutionnalisée par le vœu d'obéissance, est très importante pour Thérèse, la refuser conduisant selon elle {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Pour Théophane, la vie chrétienne ne consiste pas à faire des grandes œuvres ou des grandes actions, mais à vivre chaque jour en cherchant à aimer et à agir pour Dieu dans le quotidien. Cette conviction est source de joie pour lui, et c'est cet aspect de sa spiritualité qui fait de lui le saint de prédilection de Thérèse de Lisieux : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Cette recherche de la simplicité et de la vie ordinaire est l'un des éléments marquants dans la vie de Théophane Vénard : les témoignages posthumes rappellent sa profonde simplicité. Il ne s'est pas fait remarquer pour des attitudes ou des qualités extraordinaires : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help), témoigne l'un de ses supérieurs, qui poursuit : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Le témoignage de l'abbé Arnaud, un des condisciples de Théophane Vénard, confirme cette simplicité dans son attitude : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Dans une de ses lettres à sa sœur Mélanie, il l'invite à accomplir toutes ses actions en les faisant pour Dieu et avec lui. Reprenant l'exemple de l'évangile, il invite à vivre l'action comme Marthe de Béthanie avec l'esprit de Marie, c'est-à-dire agir tout en pensant et vivant pour Dieu : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Joy in the everyday

[edit]La vie ordinaire n'est pas exempte de difficultés et de souffrances, néanmoins la confiance que Théophane porte en Dieu le conduit à rechercher la joie en tout. Il fait de la joie sa devise. Ainsi, quand il décrit ses difficultés, tant ses problèmes de santé que les conséquences des persécutions, il écrit : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help). Pour lui, la joie et la gaîté proviennent de la confiance en Dieu. Il écrit en mars 1854 : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Il estime que la recherche de la joie et la lutte contre la tristesse sont un combat qu'il faut mener malgré les difficultés. Dans une lettre à son frère, il décrit sa conception de la recherche de la joie : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Il demande même dans ses dernières lettres, alors qu'il se sait condamné à mort, de se réjouir, comme dans sa dernière lettre à destination de ses confrères des Missions étrangères de Paris : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Cette joie est l'un des éléments que Thérèse de Lisieux admire le plus chez Théophane : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

The spirituality of Mission

[edit]Prayer, the first means of being a missionary

[edit]Théophane Vénard attribue une place primordiale à la prière dans sa mission. Pour lui, elle est le moyen de préparer la mission, et donc de permettre l'action de Dieu. Quand il part pour l'Asie, il écrit à son frère Eusèbe une lettre lui demandant de prier : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) La prière consiste aussi à agir. Dans une lettre à sa sœur Mélanie, il insiste sur le fait que l'on peut être actif tout en priant. En prenant pour exemple dans l'Évangile la rencontre de Jésus avec Marthe et Marie, il recommande à Mélanie de {{citation}}: Empty citation (help).

Thérèse de Lisieux développe la même conception de la prière comme lieu et soutien de la mission. Elle est d'ailleurs proclamée par l'Église catholique sainte patronne des missions. Elle écrit : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Spiritual fatherhood

[edit]Théophane Vénard développe sa mission au Viêt Nam en devenant le directeur spirituel des catéchistes et des religieuses. Il développe alors sa paternité spirituelle pour guider vers Dieu ceux qui lui sont confiés, et il exige discipline et étude pour aider à connaître Dieu. On retrouve ces mêmes éléments chez Thérèse de Lisieux.

Directeur spirituel des Amantes de la Croix, congrégation religieuse asiatique, Théophane exige qu'elles suivent la règle qu'il s'impose à lui-même[86]. Les Amantes de la Croix affirment qu'il {{citation}}: Empty citation (help), de même les catéchistes qui le trouvent parfois sévère[87]. Thérèse de Lisieux, maîtresse des novices au Carmel de Lisieux, est tout aussi sévère vis-à-vis des novices : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Elle ajoute : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Cette exigence qu'il développe pour les Amantes de la Croix et les catéchistes découle en partie d'une véritable ascèse de vie : les Amantes de la Croix affirment qu'il mangeait peu, deux fois par jour et ne faisait jamais de remarque désobligeante sur la quantité ou la qualité de la nourriture[89]. De même, lorsqu'il se fait soigner, il ne se plaint pas des soins malgré la souffrance occasionnée[89].

Alors qu'il supporte des conditions de vie assez difficiles, fuyant les persécutions, Théophane travaille continuellement à sa traduction de la Bible en langue annamite[90]. Il termine ainsi la traduction du Nouveau Testament pour les séminaristes et les prêtres vietnamiens, et envisage d'écrire un traité apologétique en langue annamite, comme il l'écrit le 21 mai 1860 : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Cette volonté de transmettre la foi est la même que celle de Thérèse de Lisieux, qui écrit l'Histoire d'une âme et affirme : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Spiritual combat

[edit]Dans les écrits de Théophane Vénard, le vocabulaire de la mission se rapproche du vocabulaire guerrier[92]. Pour Théophane Vénard, être missionnaire c'est combattre et devenir le soldat de Dieu : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help). C'est la même conception que Thérèse de Lisieux développe dans ses écrits {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

La conception qu'il se fait de la mission conduit Théophane à valoriser le combat et la virilité. Ce combat est avant tout une lutte contre ses défauts, mais aussi une recherche de la perfection, comme il le décrit dans une de ses lettres à son ami le père Dallet : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Devenir missionnaire est aussi comparé par Théophane Vénard à une route, un chemin à gravir, comme un athlète, demandant du courage et de la persévérance : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

The apostolate of suffering

[edit]Au XIXe siècle, la conception de la mission, appelée aussi missiologie, est inséparable de la notion de martyre. En effet, les missions en Asie sont marquées par de très nombreuses persécutions et par le martyre de nombreux catholiques. Théophane Vénard, très marqué par ces martyres, développe une vision de la mission très liée à la conception du martyre, du don de soi jusqu'à la mort[97].

Lorsqu'il subira les cinq cents brûlures dues à la moxibustion, Théophane ne se plaint pas mais prie[97]. Dans une lettre à son ami le père Dallet, il affirme qu'il faut lutter, quand on souffre, contre la désespérance et que la souffrance peut avoir des fruits : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Dans une lettre, il décrit cette offrande de sa souffrance qui peut selon lui, aider à sauver des âmes : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Thérèse de Lisieux développe la même conception de la souffrance qui, acceptée par amour, est la condition de l'apostolat : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

A painful estrangement

[edit]

Théophane Vénard se sépare de sa famille et de ses proches. Sa correspondance témoigne de la souffrance issue de cette séparation qu'il dit subir pour Dieu[101]. Cette séparation, ainsi que la différence culturelle et la solitude, sont les principaux éléments qu'il décrit dans sa correspondance comme autant de souffrances choisies pour Dieu et qui lui coûtent[102]. Néanmoins, il indique qu'elles peuvent, elles aussi, être la source d'un bienfait, au sens qu'elle purifient l'amour qu'il porte à Dieu, comme il l'écrit dans une des prières qu'il compose : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Thérèse de Lisieux voit, elle aussi, dans la séparation, la possibilité d'un amour héroïque pour Dieu : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) Elle considère cette séparation comme étant le {{citation}}: Empty citation (help) dans une lettre au père Rouland qui doit se séparer de sa famille afin d'aller en mission : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

The ultimate gift of self: martyrdom

[edit]La mission est profondément liée chez Théophane au martyre. Théophane désire en effet mourir ainsi : le martyre de Jean-Charles Cornay l'a profondément marqué dès sa jeunesse, et marque le début de sa volonté de devenir missionnaire. Mission et martyre sont indissociables dans ses écrits comme dans sa pensée. À de nombreuses reprises dans sa correspondance, il mentionne les martyrs et montre son désir de le devenir. Le martyre est envisagé comme un honneur et comme une joie : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Pour lui, le martyre représente l'ultime preuve d'amour pour Dieu, mais c'est avant tout une grâce et un honneur venant de Dieu. Même s'il désire le martyre, il cherche à l'éviter à de nombreuses reprises en fuyant les persécutions, et il échappe maintes fois aux inspections des autorités, se cachant pendant plus de deux ans afin d'éviter d'être capturé. Le martyre est une grâce qu'il considère comme un cadeau de Dieu : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Legacy

[edit]Recognition by the Catholic Church

[edit]Très tôt après sa mort, une vraie dévotion s'instaure au Viêt Nam. Les Amantes de la Croix qui l'avaient comme supérieur le considèrent très vite comme un saint[108]. La publication de ses lettres par son frère Eusèbe Vénard contribue à le faire connaître. Théophane Vénard est déclaré bienheureux le 2 mai 1909, par le pape saint Pie X, avec trente-trois autres martyrs d'Extrême-Orient[109]. Sa fête est alors célébrée le 2 février, hormis dans le diocèse de Poitiers où il est fêté le 13 février[110]. Le succès d’Histoire d'une âme, vendu à plus de 700,000 exemplaires en 1915, et la dévotion autour de Thérèse de Lisieux, qui avait Théophane pour saint de prédilection, contribuent à le faire connaître.

Le pape Jean-Paul II le canonise le 20 juin 1988, parmi les cent dix-sept martyrs du Viêt-Nam[111] · [109]. Leur fête commune est fixée au 24 novembre[62]. Sa fête, qui était fixée au 2 février, est alors déplacée au 24 novembre, pour coïncider avec celle des autres martyrs du Viêt-Nam[112].

Le corps de Théophane Vénard ainsi que les objets lui ayant appartenu sont conservés aujourd'hui au séminaire des Missions étrangères de Paris. Sa tête est restée dans la paroisse de Ke-Trü, non loin de Hanoï[62].

Posthumous influence

[edit]Le frère de Théophane, Eusèbe, devenu vicaire à la cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Poitiers, est persuadé que son frère est un saint. Il consacre sa vie à rassembler ses lettres qu'il fait publier ainsi qu'une biographie[113]. En 1864, il publie un premier recueil de lettres de Théophane à sa famille, augmentées de quelques commentaires sous le titre Vie et Correspondance de J. Théophane Vénard, prêtre de la Société des Missions étrangères, décapité pour sa foi au Tong-King[114]. En 1865, sort la deuxième édition, et en 1888, il y a déjà plus de sept rééditions. L'ouvrage est de nouveau réédité plusieurs fois sous des formats différents en 1908 et 1909 à Montligeon, et l'édition de Tours, en 1922, est la quatorzième édition de l'ouvrage[114] · [113].

La publication des lettres de Théophane Vénard dans les Annales de la propagation de la foi produit une profonde impression en France. Elles sont reprises dans des revues chrétiennes, mais également dans des revues non confessionnelles[113] · [62].

Thérèse de Lisieux, religieuse du Carmel, affirme se reconnaître en Théophane Vénard et fait de lui son martyr favori[115] et son saint de prédilection[116] : {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)[62]. Elle désire être missionnaire comme lui[117] · [118]. Pendant son agonie, elle demande qu'on lui apporte une relique de Théophane Vénard, qu'elle surnomme {{citation}}: Empty citation (help). Elle copie plusieurs passages des dernières lettres de Théophane Vénard dans son testament spirituel en les mettant au féminin et signe {{citation}}: Empty citation (help). L'influence de Thérèse de Lisieux au XXe siècle contribue en grande partie à la renommée de son saint de prédilection[109].

Eusèbe Vénard participe également à la béatification de son frère, le 2 mai 1909[113]. À l'occasion de la béatification, il fait paraître une édition beaucoup plus complète des lettres de Théophane, sous le titre Lettres Choisies du Bienheureux Théophane Vénard[114]. Mgr Francis Trochu publie en 1929 une biographie de 540 pages, considérée comme la plus complète de Théophane Vénard[114].

-

Stained glass of the blessed Théophane Vénard in the church of Notre-Dame de l'Assomption, Saint-Loup-Lamairé.

-

The relics of Théophane Vénard at the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

-

Title page of F. Trochu's work Théophane Vénard (1929)

In popular culture

[edit]Théophane Vénard bénéficie d'une certaine notoriété dans la culture populaire, qui fait de lui, un modèle du martyre à l'époque moderne.

De nombreuses écoles, collèges, lycées et autres institutions prennent son nom, spécialement dans l'enseignement catholique, comme le collège Théophane Vénard à Nantes ou l'école Théophane Vénard à Romagne.

En 1988, Chantal Goya, elle-même née au Vietnam, lui dédie une chanson, Théophane ... Théophane, sur des paroles de Jean-Jacques Debout, reprenant l'image de la petite fleur: "La mission de ton cœur fut comme la fleur qu’un matin / Au jardin du Seigneur, on est venu chercher soudain".

En 2009, Danh Vo, artiste vietnamien, reproduit la dernière lettre de Théophane Vénard, imitant sa calligraphie, pour en faire une œuvre d'art: 2.02.1861[119].

Notes and references

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 10

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 11

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 12-13

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 14

- ^ a b c Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 15

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 16

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 17

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Simonnet23was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 24

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 25

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 30

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 32

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 36

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 33

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 37

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 40

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 42

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 44

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Simonnet46was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 36

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 47

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 49

- ^ a b c d e f Gilles Reithinger 2010, p. 128

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 54

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 56

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 58

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 61

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 63

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 65

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Simonnet67was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

ReferenceAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 68

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 69

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 71

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 78

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 79

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 80

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 81

- ^ a b c Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 85

- ^ a b c d e f Gilles Reithinger 2010, p. 132

- ^ Lettres Gilles Reitheinger 2010, p. 160

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 90

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 88

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 91

- ^ a b c d e f Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 95

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 96

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 94

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 98

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 99

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 102

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 103

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 104

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 97

- ^ a b c d e Gilles Reithinger 2010, p. 133

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 109

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 106

- ^ a b Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 114

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 29

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 118

- ^ Gilles Reithinger 2010, p. 133-134

- ^ Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 127

- ^ a b c d e f Gilles Reithinger 2010, p. 134

- ^ Paris Foreign Missions Society. "Saint Théophane Vénard". http://animation.mepasie.org/. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 51

- ^ a b Guennou, Lettres choisies et présentées 1982, p. 35

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 49

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 74

- ^ Guennou, Lettres choisies et présentées 1982, p. 171

- ^ http://www.carmel.asso.fr/Le-livre-de-la-Parole-et-celui-de.html

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 81

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 80

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 87

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 137

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 72

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 210

- ^ Thérèse de Lisieux, Œuvres complètes, Éditions du Cerf/Desclée de Brouwer, 1992, p. Missing parameter/s! (Template:P.)248 ISBN 2-204-04303-6

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 96

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 67

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 62

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 172

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 183

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 193

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 184

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 61

- ^ Guennou, Lettres choisies et présentées 1982, p. 122

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 139

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 142

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 140

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 162

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 153

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 151

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 132

- ^ Lettres Gilles Reitheinger 2010, p. 51

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 133

- ^ Lettres Gilles Reitheinger 2010, p. 50

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 135

- ^ a b Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 129

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 134

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 158

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 157

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 120

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 121

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 122

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 167

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 166

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 191

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 209

- ^ Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 139

- ^ a b c Gabriel Emonnet, Théophane et Thérèse 1988, p. 8

- ^ Nominis : Jean-Théophane Vénard

- ^ Jean-Paul II (1988). "Discours du Saint-Père Jean-Paul II aux pèlerins français et espagnols venus à Rome à l'occasion de la canonisation de 117 martyrs du Vietnam". Vatican.va. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ "Saint Théophane Vénard". http://animation.mepasie.org/. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ a b c d e Christian Simonnet 1992, p. 138

- ^ a b c d Guennou, Lettres choisies et présentées 1982, p. 12

- ^ Gilles Reithinger 2010, p. 122

- ^ Conférence du Cardinal Ennio Antonelli Président du Conseil Pontifical pour la Famille sur le site officiel du Vatican.va, consulté le 3 avril 2012

- ^ Jean-Paul II (1980). "Homélie du Saint-Père Jean-Paul II à Lisieux en le 2 juin 1980". Vatican.va. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Ennio Antonelli (2010). "Conférence du Cardinal Ennio Antonelli Président conseil pontifical pour la Famille : "La famille chrétienne acteur d'évangélisation"". Vatican.va. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ (in English) Carol Vogel (1er novembre 2012), Native of Vietnam Wins Hugo Boss Prize New York Times.

To learn more

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]{{légende plume}}

Works of Théophane Vénard

[edit]- Théophane Vénard (second semestre 2011). Lettres (in French). France: Fremur. p. 200. ISBN 978-2-95252-523-7. Lettres Gilles Reitheinger.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|publi=and|collection=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help){{plume}} - Théophane Vénard, Jean Guennou (December 1982). Bienheureux Théophane Vénard (in French). France: Tequi. p. 190. ISBN 2-85244-535-2. Guennou.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|publi=and|collection=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help){{plume}}

Comic book

[edit]- Brunor, Dominique Bar, Géraldine Gilles (2007). Théophane Vénard (in French). France: CLD éditions. p. 46. ISBN 9782854435092.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|collection=and|publi=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Francis Ferrier, llustrations de Paul Ordner (1 January 1961). Dans les griffes d'ong-kop. le bienheureux theophane venard. Fleurus.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|sous-titre=and|publi=(help); Unknown parameter|collection=ignored (help)

Biographies

[edit]- Gilles Reithinger (November 2010). Vingt-Trois Saints pour l'Asie (in French). France: CLD éditions et Paris Foreign Missions Society. p. 280. ISBN 978-2-85443-548-1. Gilles Reithinger.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|sous-titre=,|publi=, and|collection=(help) {{plume}} - Jean Theophane Venard (Auteur), Mary Elizabeth Herbert (Traduction) (September 2010). Life of Jean Theophane Venard, Martyr in Tonquin (in Anglais). Kessinger Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-1165423767.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|collection=and|publi=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Mary Elizabeth Herbert & Theophane Venard (Auteur) (4 February 2010). A Modern Martyr: Theophane Venard (in Anglais). Nabu Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1143751578.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|publi=(help); Unknown parameter|collection=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Christian Simonnet (November 1992). Théophane (in French). France: Broché & La Salle des martyrs. p. 141. ISBN 978-2213012865. Christian Simonnet.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|publi=and|collection=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help){{plume}} - Gabriel Emonnet (January 1988). 2 athlètes de la foi (in French). France: Téqui. p. 265. ISBN 2-85244-855-6. Gabriel Emonnet.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|publi=and|collection=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help) {{plume}} - Agnès Richomme, Le Bienheureux Théophane Vénard, illustrations de Robert Rigot, Éditions Fleurus, 1961

- Jean Guennou, Bienheureux Théophane Vénard, Édition Soleil Levant, 1959

- Jacques Nanteuil, Gaston Giraudias, L'Épopée missionnaire de Théophane Vénard, 1950

- R.P. Destombes, Une amitié spirituelle, Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux et le bienheureux Théophane Vénard, 1945

- Francis Trochu (1 January 1929). Le Bienheureux Théophane Vénard (in Français). Lyon: Librairie Emmanuel Vitte. p. 537.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|collection=and|publi=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - M. l'abbé J.-B. Chauvin, Jean-Théophane Vénard (Auteur), Eusèbe Vénard (Auteur) (1865). Vie et correspondance de J.-Théophane Vénard, (in French). France: H. Oudin. p. 376. ASIN B001D6HE90.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|publi=and|collection=(help); Unknown parameter|sous-titre=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Articles and discourses

[edit]- Louis-Édouard Pie, Discours prononcé par Mgr. l'évêque de Poitiers, le 2 février 1862, dans l'église paroissiale de Saint-Loup, à l'occasion du premier anniversaire du martyre de M. J. Théophane Venard, décapité pour la foi au Tong-King, éd. H. Oudin, 1862, 16 pages

- E.-P. Menne, Centenaire de la naissance du bienheureux Théophane Vénard, prêtre-martyr de la Société des Missions étrangères de Paris. Panégyrique prononcé par le R. P. Menne… en l'église cathédrale d'Hanoï, Tonkin, le 24 novembre 1929, éd. Impr. I.D.I.O.H.G., 1930

- Jean-Paul II (1988). "Discours du Saint-Père Jean-Paul II aux pèlerins français et espagnols venus à Rome à l'occasion de la canonisation de 117 Martyrs du Vietnam". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

Linked articles

[edit]{{Palette|Missions étrangères de Paris}} {{Article de qualité|oldid=79640652|date=17 juin 2012}}

Catégorie:Prêtre catholique français du XIXe siècle

Catégorie:Condamné à mort exécuté par décapitation

Catégorie:Missionnaire français au Tonkin

Catégorie:Missions étrangères de Paris

Theophane Venard

Theophane Venard

Theophane Venard

Catégorie:Béatification par le pape Pie X

Catégorie:Personnalité liée au Carmel

Catégorie:Catholicisme au Viêt Nam

Catégorie:Naissance en novembre 1829

Catégorie:Naissance dans les Deux-Sèvres

Catégorie:Décès en février 1861

Catégorie:Décès à Hanoï

Catégorie:Décès à 31 ans

Catégorie:Martyr du Viêt Nam

Catégorie:Missionnaire catholique français

Catégorie:Martyr catholique au XIXe siècle