User:Jonyungk/Sandbox

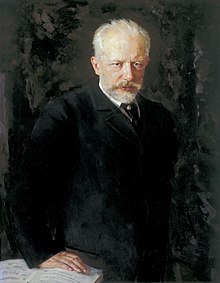

While the contributions of the Russian nationalistic group The Five were important in their own right in developing an independent Russian voice and consciousness in classical music, the compositions of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky became dominant in 19th century Russia, with Tchaikovsky becoming known both in and outside Russia as its greatest musical talent. His formal conservatory training allowed him to write works with Western-oriented attitudes and techniques, showcasing a wide range and breadth of technique from a poised "Classical" form simulating 18th century Rococo elegance to a style more characteristic of Russian nationalists or a musical idiom expressly to channel his own overwrought emotions.[1]

Even with this compositional diversity, the outlook in Tchaikovsky's music remains essentially Russian, both in its use of native folk song and its composer's deep absorption in Russian life and ways of thought.[1] Writing about Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty in an open letter to impresario Sergei Diaghilev that was printed in the Times of London, composer Igor Stravinsky contended that Tchaikovsky's music was as Russian as Pushkin's verse or Glinka's song, since Tchaikovsky "drew unconsciously from the true, popular sources" of the Russian race.[2] This Russianness of mindset ensured that Tchaikovsky would not become a mere imitator of Western technique. Tchaikovsky's natural gift for melody, based mainly on themes of tremendous eloquence and emotive power and supported by matching resources in harmony and orchestration, has always made his music appealing to the public. However, his hard-won professional technique and an ability to harness it to express his emotional life gave Tchaikovsky the ability to realize his potential more fully than any other Russian composer of his time.[3]

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) wrote several works well known among the general classical public—Romeo and Juliet, the 1812 Overture, his three ballets The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, and The Sleeping Beauty. These, along with two of his four concertos, three of his six symphonies (seven if Manfred is included) and two of his 10 operas, are probably among his most familiar works. Almost as popular are the Manfred Symphony, Francesca da Rimini, the Capriccio Italien and the Serenade for Strings. His three string quartets and piano trio all contain beautiful passages, while recitalists still perform at least some of his 106 songs.[4] Tchaikovsky also wrote over 100 piano works, which range the entire span of his creative life. While some of these can be challenging technically, they are mostly charming, unpretentious compositions intended for amateur pianists.[5] However, there is more attractive and resourceful music in some of these pieces than one might be inclined to expect.[6]

Tchaikovsky's formal conservatory training allowed him to write works with Western-oriented attitudes and techniques. His music showcases a wide range and breadth of technique, from a poised "Classical" form simulating 18th century Rococo elegance, to a style more characteristic of Russian nationalists, or a musical idiom expressly to channel his own overwrought emotions.[7] Despite his reputation as a "weeping machine,"[4] self-expression was not a central principle for Tchaikovsky. In a letter to von Meck dated December 5, 1878, he explained there were two kinds of inspiration for a symphonic composer, a subjective and an objective one, and that program music could and should exist, just as it was impossible to demand that literature make do without the epic element and limit itself to lyricism alone. Correspondingly, the large scale orchestral works Tchaikovsky composed can be divided into two categories—symphonies in one category, and other works such as symphonic poems in the other. Both categories were equally valid.[8] Program music such as Francesca da Rimini or the Manfred Symphony was as much a part of the composer's artistic credo as the expression of his "lyric ego."[9] There is also a group of compositions which fall outside the dichotomy of program music versus "lyrical ego," where he hearkens toward pre-Romantic aesthetics. Works in this group include the four orchestral suites, Capriccio Italien, the Violin Concerto and the Serenade for Strings.[10]

- ^ a b Brown, New Grove, 18:606.

- ^ Stravinsky, Igor, "An Open Letter to Diaghilev," The Times, London, October 18, 1921. As quoted in Holden, 51.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:606-7, 628.

- ^ a b Schonberg, 367.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 118.

- ^ Brown, The Final Years, 408.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:606.

- ^ Wood, 75.

- ^ Maes, 154.

- ^ Maes, 154–155.