User:JMvanDijk/Sandbox 9/Box 26/Box 3

| National Order of the Legion of Honour Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur | |

|---|---|

Current version of the Grand Cross of the order given by President René Coty to Dutch Prime Minister Willem Drees | |

| Awarded by President of France | |

| Type | Order of merit |

| Established | 19 May 1802 |

| Country | France |

| Motto | Honneur et patrie ("Honour and Fatherland") |

| Eligibility | Military and civilians |

| Awarded for | Excellent civil or military conduct delivered, upon official investigation |

| Founder | Napoleon Bonaparte |

| Grand Master | Emmanuel Macron, President of France |

| Grand Chancellor | François Lecointre |

| Secretary-General | Julien Le Gars |

| Classes | (in 2010)

|

| Statistics | |

| First induction | 15 July 1804 |

| Precedence | |

| Next (higher) | None |

| Next (lower) |

|

Ribbon bars of the order | |

History

[edit]First Empire

[edit]In a decree issued on the 10 Pluviôse XIII (30 January 1805), a grand decoration was instituted. This decoration, a cross on a large sash and a silver star with an eagle, symbol of the Napoleonic Empire, became known as the Grand aigle (Grand Eagle), and later in 1814 as the Grand cordon (big sash, literally "big ribbon"). After Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of the French in 1804 and established the Napoleonic nobility in 1808, award of the Légion d'honneur gave right to the title of "Knight of the Empire" (Chevalier de l'Empire). The title was made hereditary after three generations of grantees.

Napoleon had dispensed 15 golden collars of the Légion d'honneur among his family and his senior ministers. This collar was abolished in 1815.

Although research is made difficult by the loss of the archives, it is rumoured that three women who fought with the army were decorated with the order: Virginie Ghesquière, Marie-Jeanne Schelling and a nun, Sister Anne Biget.[a]

The Légion d'honneur was prominent and visible in the French Empire. The Emperor always wore it, and the fashion of the time allowed for decorations to be worn most of the time. The king of Sweden therefore declined the order; it was too common in his eyes. Napoleon's own decorations were captured by the Prussians and were displayed in the Zeughaus (armoury) in Berlin until 1945. Today, they are in Moscow.

-

First Légion d'Honneur investiture, 15 July 1804, at Saint-Louis des Invalides by Jean-Baptiste Debret (1812)

-

A depiction of Napoleon making some of the first awards of the Legion of Honour, at a camp near Boulogne on 16 August 1804

-

As Emperor, Napoleon always wore the Cross and Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honour.[citation needed]

-

Embroidered insignia of the Legion of Honour, detail of Napoleon's uniform of colonel of the Chasseurs à cheval of the Imperial Guard

Consulate

[edit]During the French Revolution, all of the French orders of chivalry were abolished and replaced with Weapons of Honour. It was the wish of Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul, to create a reward to commend civilians and soldiers. From this wish was instituted a Légion d'honneur,[2] a body of men that was not an order of chivalry, for Napoleon believed that France wanted a recognition of merit rather than a new system of nobility. However, the Légion d'honneur did use the organization of the old French orders of chivalry, for example, the Ordre de Saint-Louis. The insignia of the Légion d'honneur bear a resemblance to those of the Ordre de Saint-Louis, which also used a red ribbon.[3]

Napoleon originally created this award to ensure political loyalty. The organization would be used as a façade to give political favours, gifts, and concessions.[4] The Légion d'honneur was loosely patterned after a Roman legion, with legionaries, officers, commanders, regional "cohorts" and a grand council. The highest rank was not a Grand Cross but a Grand aigle (Grand Eagle), a rank that wore the insignia common to a Grand Cross. The members were paid, the highest of them extremely generously:

- 5,000 francs to a grand officier,

- 2,000 francs to a commandeur,

- 1,000 francs to an officier,

- 250 francs to a légionnaire.

Napoleon famously declared, "You call these baubles, well, it is with baubles that men are led... Do you think that you would be able to make men fight by reasoning? Never. That is good only for the scholar in his study. The soldier needs glory, distinctions, rewards."[5] This has been often quoted as "It is with such baubles that men are led." Napoleon was also occasionally noted after a battle to ask who the bravest man in a regiment was, and upon the regiment declaring the individual, the Emperor would take the Legion d'Honneur of his own coat and pin it on the chest of the man.[6]

The order was the first modern order of merit. Under the monarchy, such orders were often limited to Roman Catholics, all knights had to be noblemen, and military decorations were restricted to officers.[citation needed] The Légion d'honneur, however, was open to men of all ranks and professions; only merit or bravery counted. The new legionnaire had to be sworn into the Légion d'honneur. All previous orders were Christian, or shared a clear Christian background, whereas the Légion d'honneur is a secular institution. The badge of the Légion d'honneur has five arms.

| Legion of Honour ribbons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fourth and Fifth Republics

[edit]The establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1946 brought about the latest change in the design of the Legion of Honour. The date "1870" on the obverse was replaced by a single star. No changes were made after the establishment of the Fifth Republic in 1958.

Classes and insignia

[edit]

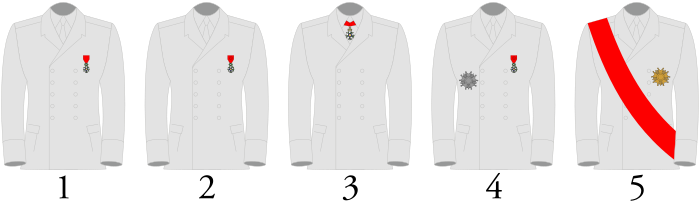

The order has had five levels since the reign of King Louis XVIII, who restored the order in 1815. Since the reform, the following distinctions have existed:

- Three ranks:

- Chevalier (Knight): badge worn on left breast suspended from ribbon

- Officier (Officer): badge worn on left breast suspended from a ribbon with a rosette

- Commandeur (Commander): badge around neck suspended from ribbon necklet

- Two dignities:

- Grand officier (Grand Officer): badge worn on left breast suspended from a ribbon (Officer), with star displayed on right breast

- Grand-croix (Grand Cross), formerly Grande décoration, Grand aigle, or Grand cordon: the highest level; badge affixed to sash worn over the right shoulder, with star displayed on left breast

Due to the order's long history, and the remarkable fact that it has been retained by all subsequent governments and regimes since the First Empire, the order's design has undergone many changes. Although the basic shape and structure of the insignia has remained generally the same, the hanging device changed back and forth and France itself swung back and forth between republic and monarchy. The central disc in the centre has also changed to reflect the political system and leadership of France at the time. As each new regime came along the design was altered to become politically correct for the time, sometimes even changed multiple times during one historical era.

The badge of the Légion is shaped as a five-armed "Maltese Asterisk", using five distinctive "arrowhead" shaped arms inspired by the Maltese Cross. The badge is rendered in gilt (in silver for chevalier) enameled white, with an enameled laurel and oak wreath between the arms. The obverse central disc is in gilt, featuring the head of Marianne, surrounded by the legend République Française on a blue enamel ring. The reverse central disc is also in gilt, with a set of crossed tricolores, surrounded by the Légion's motto Honneur et Patrie ('Honour and Fatherland') and its foundation date on a blue enamel ring. The badge is suspended by an enameled laurel and oak wreath.

The star (or plaque) is worn by the Grand Cross (in gilt on the left chest) and the Grand Officer (in silver on the right chest) respectively; it is similar to the badge, but without enamel, and with the wreath replaced by a cluster of rays in between each arm. The central disc features the head of Marianne, surrounded by the legend République Française ('French Republic') and the motto Honneur et Patrie.[7]

The ribbon for the medal is plain red.

The badge or star is not usually worn, except at the time of the decoration ceremony or on a dress uniform or formal wear. Instead, one normally wears the ribbon or rosette on their suit.

For less formal occasions, recipients wear a simple stripe of thread sewn onto the lapel (red for chevaliers and officiers, silver for commandeurs). Except when wearing a dark suit with a lapel, women instead typically wear a small lapel pin called a barrette. Recipients purchase the special thread and barrettes at a store in Paris near the Palais-Royal.[8]

| Historical Era/Period | Notes | Obverse | Reverse | Hanging Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1804 | The first model of the Legion d'Honneur did not hang from a crown or wreath. It lasted for just 9 months from May 1804 until February 1805 and encompassed the founding of the First French Empire on the 18th May 1804. Despite being officially established on 19 May 1802, no awards were made until this version. This version shows the Emperor on the obverse and the imperial eagle on the reverse. The text on the ring on both the obverse and reverse would remain the same during the entirety of Napoleon's reign. |

|

|

|

| 1805 | The second model of differed only from the first by the addition of the imperial crown atop the cross, and was attached to one of the arms of the cross. The image of the Emperor is also slightly smaller than the previous version, while the reverse ring also has a stylised wreath at the bottom instead of three stars. |

|

|

|

| 1806–1808 | The third model is very similar to the previous second version however the depiction of Napoleon is more similar to the first version and the obverse ring has a wreath at the bottom. The crown, while almost identical to that of the second version this time is free-hanging and separately fixed above the cross. |

|

|

|

| 1808–1809 | The fourth model has as slightly different depiction of the Emperor while the obverse ring has a star and dots in place of the previous versions wreath. The reverse of the fourth model is notable as its the only First Empire model with the eagle facing to the right, while the bottom of the ring has three stars reminiscent of the first model. The crown the cross hangs from is also very different compared to the previous two versions. |

|

|

|

| 1809–1814 | The fifth and final version of the First Empire is different from the other versions by the execution of larger text on the rings, with the reverse showing a distinct wreath like object at the bottom. The obverse on some models shows and enamelled laurel wreath adorning the Emperors head, while on the reverse the eagle is back facing left. The crown is also radically different from the previous models. |

|

|

|

| 1814–1830 | The sixth model from the Bourbon Restoration period marks the first major alteration from the original design, due to the fact that the regime and leader of France had changed. The crown the cross hangs from has been altered and also features the main symbol of the House of Bourbon; the fleur-de-lis. The obverse features the profile of "The Good King" Henri IV with the text of the ring bearing the words; Henry IV, King of France and the Navarre. The reverse keeps the text of the previous versions; Honneur et Patrie and depicts the three fleurs-de-lis, the symbol of the Bourbons. |

|

|

|

| 1830–1848 | The seventh model from the July Monarchy period is similar to the previous Bourbon Restoration period. The crown is very similar, with just the fleur-de-lis omitted, the obverse keeps the profile of Henri IV but the obverse ring bears just his name, with the rest of the ring filled with stars and a wreath. The reverse bears the first depiction of what would continue for many future iterations; the two crossed tricolours with the usual reverse ring motto Honneur et Patrie. |

|

|

|

| 1848–1851 | The eighth model, used for only three years during the Second Republic is the only other example apart from the first model to not have any hanging device (no crown/wreath). The obverse once again shows a portrait of Napoleon, with the text reading "Bonaparte First Consul" and the date of the order's founding; 19 May 1802. The reverse shows the crossed tricolours as before, however this time the Honneur et Patrie is written underneath and not on the ring, the first and only time this was the case. The reverse ring instead reads République Française which would later feature on the obverse ring. |

|

|

|

| 1851–1852 | The ninth or La Presidence model was only used between 1851 and 1852 and is considered by some to be a hybrid model. It is at the very least a transitional model from the design used during the Second Republic to the Second Empire. The execution of the cross is very similar to Second Republic models, just with the addition of a crown (different to that of the Second Empire models) while the obverse continues to show Napoleon, with the ring text of Napoleon Emp. des Français. The reverse shows the imperial eagle and the usual ring text. The central discs bear a striking resemblance to the fifth model. |

|

|

|

| 1852–1870 | The tenth model used in the Second Empire would be the last to date to use either Napoleon's image or a crown of any sort. The crown used is quite unique and resembles the Crown of Napoleon III, while the obverse shows the Napoleon I with the ring text of Napoleon Empereur des Français (the only model to fully spell out Emperor). The reverse shows the usual imperial eagle, though this time facing right like the fourth model. The usual reverse ring text is present with a large wreath at the bottom. |

|

|

|

| 1870–1940 | The eleventh model created for the Third French Republic would be another radical change, and the first to show much of the symbolism of today's model. It was the first model to hang from a wreath of laurel and oak leaves, and the first to feature the profile of Marianne on the obverse. The ring on the obverse reads; République Française, the first since the early Second Republic and the first time on the obverse, with the date 1870. The back features the tricolours and the usual text of Honneur et Patrie, in a design almost identical to the seventh model used during the July Monarchy. |

|

|

|

| 1946– | The 12th, final and current version is almost identical to the 11th. The only differences are found on the ring of the obverse, where the date of 1870, the Third Republic's founding, is replaced with a star. The reverse is also almost identical, with just the wreath at the bottom of the ring being replaced with 29 Floréal an X (29 Floréal Year 10), the date of the order's founding (19 May 1802) in the French Revolutionary Calendar. Except for these changes the Legion d'Honneur has remained unchanged from 1870, with this exact form being kept during both the Fourth and current Fifth Republic. |

|

|

|

Gallery SVGs

[edit]See: Category:Badges of the Legion of Honour

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Chevalier Type 1st

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Chevalier Type 2nd

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Chevalier Type 3rd

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Chevalier Type 4th

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Officier Type 1st

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Officier Type 2nd

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Officier Type 3rd

-

Légion d'honneur First Empire Officier Type 4th

- ^ Le petit Larousse 2013, p.1567.

- ^ Pierre-Louis Roederer, "Speech Proposing the Creation of a Legion of Honour", Napoleon: Symbol for an Age, A Brief History with Documents, ed. Rafe Blaufarb (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2008), 101–102.

- ^ Baetjer, Katharine (15 April 2019). French Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Early Eighteenth Century through the Revolution. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-661-7.

- ^ Jones, Colin (20 October 1994). The Cambridge Illustrated History of France (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-521-43294-4.

- ^ Antoine Claire Thibaudeau (1827). Mémoires sur le Consulat. 1799 à 1804 [Memories of the Consulate, 1799–1804] (in French). Paris: Chez Ponthieu et Cie. pp. 83–84.

- ^ Napoleon PBS Documentary 3 Of 4, retrieved 22 January 2023

- ^ "The Legion of Honor in 10 questions". The Grand Chancery of the Legion of Honour. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Donadio, Rachel (11 May 2008). "That Isn't Lint on My Lapel, I'm an Officier". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

![As Emperor, Napoleon always wore the Cross and Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honour.[citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Napoleon_Paul_Delaroche.jpg/136px-Napoleon_Paul_Delaroche.jpg)