User:Homonihilis/sandbox

Homonihilis/sandbox | |

|---|---|

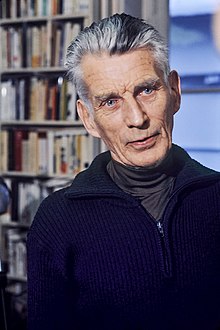

Beckett in 1977 | |

| Born | Samuel Barclay Beckett 13 April 1906 Foxrock, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 22 December 1989 (aged 83) Paris, France |

| Pen name | Andrew Belis[1] |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, poet, theatre director, essayist |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Genre | Drama, fiction, poetry, screenplays |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Murphy (1938) Molloy (1951) Malone Dies (1951) The Unnamable (1953) Waiting for Godot (1953) Watt (1953) Endgame (1957) Krapp's Last Tape (1958) How It Is (1961) |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1969 Croix de Guerre 1945 |

Samuel Barclay Beckett (13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish avant-garde novelist, playwright, theatre director, and poet, who lived in Paris for most of his adult life and wrote in both English and French. His work offers a bleak, tragicomic outlook on human nature, often coupled with black comedy and gallows humour.

Beckett is widely regarded as among the most influential writers of the 20th century. Strongly influenced by James Joyce, he is considered one of the last modernists. As an inspiration to many later writers, he is also sometimes considered one of the first postmodernists. He is one of the key writers in what Martin Esslin called the "Theatre of the Absurd". His work became increasingly minimalist in his later career.

Beckett was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his writing, which—in new forms for the novel and drama—in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation". He was elected Saoi of Aosdána in year 1984.

Early writings

[edit]Beckett studied French, Italian, and English at Trinity College, Dublin from 1923 to 1927 (one of his tutors was the eminent Berkeley scholar A. A. Luce). Beckett graduated with a BA, and—after teaching briefly at Campbell College in Belfast—took up the post of lecteur d'anglais in the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. While there, he was introduced to renowned Irish author James Joyce by Thomas MacGreevy, a poet and close confidant of Beckett who also worked there. This meeting had a profound effect on the young man. Beckett assisted Joyce in various ways, one of which was research towards the book that became Finnegans Wake.[2]

In 1929, Beckett published his first work, a critical essay entitled "Dante... Bruno. Vico.. Joyce". The essay defends Joyce's work and method, chiefly from allegations of wanton obscurity and dimness, and was Beckett's contribution to Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress (a book of essays on Joyce which also included contributions by Eugene Jolas, Robert McAlmon, and William Carlos Williams). Beckett's close relationship with Joyce and his family cooled, however, when he rejected the advances of Joyce's daughter Lucia owing to her progressing schizophrenia. Beckett's first short story, "Assumption", was published in Jolas's periodical transition. The next year he won a small literary prize with his hastily composed poem "Whoroscope", which draws on a biography of René Descartes that Beckett happened to be reading when he was encouraged to submit.

In 1930, Beckett returned to Trinity College as a lecturer, though he soon became disillusioned with the post. He expressed his aversion by playing a trick on the Modern Language Society of Dublin. Beckett read a learned paper in French on a Toulouse author named Jean du Chas, founder of a movement called Concentrism. Chas and Concentrism, however, were pure fiction, having been invented by Beckett to mock pedantry. When Beckett resigned from Trinity at the end of 1931, his brief academic career was terminated. He commemorated it with the poem "Gnome", which was inspired by his reading of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and eventually published in the Dublin Magazine in 1934:

Spend the years of learning squandering

Courage for the years of wandering

Through a world politely turning

From the loutishness of learning[3]

Beckett travelled in Europe. He spent some time in London, where in 1931 he published Proust, his critical Schopenhauerian study of French author Marcel Proust. Two years later, following his father's death, he began two years' treatment with Tavistock Clinic psychoanalyst Dr. Wilfred Bion, who took him to hear Carl Jung's third Tavistock lecture, an event which Beckett still recalled many years later. The lecture focused on the subject of the "never properly born." Aspects of it became evident in Beckett's later works, such as Watt and Waiting for Godot.[4] In 1932, he wrote his first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, but after many rejections from publishers decided to abandon it (it was eventually published in 1993). Despite his inability to get it published, however, the novel served as a source for many of Beckett's early poems, as well as for his first full-length book, the 1933 short-story collection More Pricks Than Kicks.

Beckett published a number of essays and reviews, including "Recent Irish Poetry" (in The Bookman, August 1934) and "Humanistic Quietism", a review of his friend Thomas MacGreevy's Poems (in The Dublin Magazine, July–September 1934). They focused on the work of MacGreevy, Brian Coffey, Denis Devlin and Blanaid Salkeld, despite their slender achievements at the time, comparing them favourably with their Celtic Revival contemporaries and invoking Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and the French symbolists as their precursors. In describing these poets as forming "the nucleus of a living poetic in Ireland", Beckett was tracing the outlines of an Irish poetic modernist canon.[5]

"Abbott, Lemuel (1760-1803)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Fathoms from Anywhere – A Samuel Beckett Centenary Exhibition

- ^ Knowlson (1997) p106.

- ^ "Gnome" from Collected Poems

- ^ Beckett, Samuel. (1906–1989) – Literary Encyclopedia

- ^ Disjecta, 76