User:HistoryofIran/Xerxes I

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:HistoryofIran/Xerxes_I. |

| Xerxes I 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings Great King King of Persia King of Babylon Pharaoh of Egypt King of Countries | |

| |

| King of the Achaemenid Empire | |

| Reign | October 486 – August 465 BC |

| Predecessor | Darius the Great |

| Successor | Artaxerxes I |

| Born | c. 518 BC |

| Died | August 465 BC (aged approximately 53) |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Amestris |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Achaemenid |

| Father | Darius the Great |

| Mother | Atossa |

| Religion | Indo-Iranian religion (possibly Zoroastrianism) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Xerxes (Xašayaruša/Ḫašayaruša)[2] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Xerxes I (Old Persian: 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠, romanized: Xšaya-ṛšā; c. 518 – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of Darius the Great (r. 522 – 486 BC) and his mother was Atossa, a daughter of Cyrus the Great (r. 550 – 530 BC), the first Achaemenid king.

Inheriting a vast empire stretching from Libya to Bactria, Xerxes spent his early years consolidating his power and suppressing a revolt in Egypt and then subsequently Babylonia.

Xerxes is identified with the fictional king Ahasuerus in the biblical Book of Esther.[3]

Etymology

[edit]Xérxēs (Ξέρξης) is the Greek and Latin (Xerxes, Xerses) transliteration of the Old Iranian Xšaya-ṛšā ("ruling over heroes"), which can be seen by the first part xšaya, meaning "ruling", and the second ṛšā, meaning "hero, man".[4] The name of Xerxes was known in Akkadian as Ḫi-ši-ʾ-ar-šá and in Aramaic as ḥšyʾrš.[5] Xerxes would become a popular name amongst the rulers of the Achaemenid Empire.[4]

Historiography

[edit]Much of Xerxes' bad reputation is due to propaganda by the Macedonian king Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC), who had him vilified.[6] The modern historian Richard Stoneman regards the portrayal of Xerxes as more nuanced and tragic in the work of the contemporary Greek historian Herodotus.[6] However, many modern historians agree that Herodotus recorded spurious information.[7][8] Pierre Briant has accused him of presenting a stereotyped and biased portrayal of the Persians.[9] Many Achaemenid-era clay tablets and other reports written in Elamite, Akkadian, Egyptian and Aramaic are frequently contradictory to the reports of classical authors, i.e. Ctesias, Plutarch and Justin.[10] However, without these historians, a lot of information regarding the Achaemenid Empire is missing.[11]

Early life

[edit]Parentage and birth

[edit]Xerxes' father was Darius the Great (r. 522 – 486 BC), the incumbent monarch of the Achaemenid Empire, albeit himself not a member of the family of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the empire.[12][13] His mother was Atossa, a daughter of Cyrus.[14] They had married in 522 BC,[15] with Xerxes being born in c. 518 BC.[16]

Upbringing and education

[edit]According to the Greek dialogue First Alcibiades, which describes typical upbringing and education of Persian princes; they were raised by eunuchs. When reaching the age of 7, they learn how to ride and hunt; at age 14, they are looked after by four teachers of aristocratic stock, who teach them how to be "wise, just, prudent and brave."[17] Persian princes were also taught on the basics of the Zoroastrian religion, to be truthful, have self-restraint, and to be courageous.[17] The dialogue further adds that "Fear, for a Persian, is the equivalent of slavery."[17] At the age of 16 or 17, they begin their "national service" for 10 years, which included practicing archery and javelin, competing for prizes, and hunting.[18] Afterwards they serve in the military for around 25 years, and are then elevated to the status of elders and advisers of the king.[18]

This account of education amongst the Persian elite is supported by Xenophon's description of the 5th-century BC Achaemenid prince Cyrus the Younger, whom he was well-acquainted with.[18] Stoneman suggests that this was the type of upbringing and education that Xerxes experienced.[19] It is unknown if Xerxes ever learned to read or write, with the Persians favouring oral history over written literature.[19] Stoneman suggests that Xerxes' upbringing and education was possibly not much different from that of the later Iranian kings, such as Abbas the Great, king of the Safavid Empire in the 17th-century AD.[19] Starting from 498 BC, Xerxes resided in the royal palace of Babylon.[20]

Accession to the throne

[edit]After becoming aware of the Persian defeat at the Battle of Marathon, Darius began planning another expedition against the Greek-city states; this time, he, not Datis, would command the imperial armies.[21] Darius had spent three years preparing men and ships for war when a revolt broke out in Egypt. This revolt in Egypt worsened his failing health and prevented the possibility of his leading another army.[21] Soon after, Darius died. In October 486 BCE, the body of Darius was embalmed and entombed in the rock-cut tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam, which he had been preparing.[21] Xerxes succeeded to the throne; however, prior to his accession, he contested the succession with his elder half-brother Artobarzanes, Darius's eldest son who was born to his first wife before Darius rose to power.[22] With Xerxes' accession, the empire was again ruled by a member of the house of Cyrus.[21]

Consolidation of power

[edit]

At Xerxes' accession, trouble was brewing in some of his domains. A revolt occurred in Egypt, which seems to have been dangerous enough for Xerxes to personally lead the army to restore order (which also gave him the opportunity to begin his reign with a military campaign).[23] Xerxes surpressed the revolt in January 484 BC, and appointed his full-brother Achaemenes as satrap of the country, replacing the previous satrap Pherendates, who was reportedly killed during the revolt.[24][20] The supression of the Egyptian revolt expended the army, which had been mobilized by Darius over the previous three years.[23] Xerxes thus had to raise another army for his expedition into Greece, which would take four years.[23] There was also unrest in Babylon, which revolted at least twice against Xerxes. The first revolt broke out in June or July of 484 BC and was led by a rebel of the name Bel-shimanni. Bel-shimmani's revolt was short-lived, Babylonian documents written during his reign only account for a period of two weeks.[25]

Two years later, Babylon produced another rebel leader, Shamash-eriba. Beginning in the summer of 482 BC, Shamash-eriba seized Babylon itself and other nearby cities, such as Borsippa and Dilbat, and was only defeated in March 481 BC after a lengthy siege of Babylon.[25] The precise cause of the unrest in Babylon is uncertain.[23] It may have been due to tax increase.[26] Prior to these revolts, Babylon had occupied a special position within the Achaemenid Empire, the Achaemenid kings had been titled as "King of Babylon" and "King of the Lands", perceiving Babylonia as a somewhat separate entity within their empire, united with their own kingdom in a personal union. Xerxes dropped "King of Babylon" from his titulature and divided the previously large Babylonian satrapy (accounting for most of the Neo-Babylonian Empire's territory) into smaller sub-units.[27]

Using texts written by classical authors, it is often assumed that Xerxes enacted a brutal vengeance on Babylon following the two revolts. According to ancient writers, Xerxes destroyed Babylon's fortifications and damaged the temples in the city.[25] The Esagila was allegedly exposed to great damage and Xerxes allegedly carried the statue of Marduk away from the city,[28] possibly bringing it to Iran and melting it down (classical authors held that the statue was entirely made of gold, which would have made melting it down possible).[25] Modern historian Amélie Kuhrt considers it unlikely that Xerxes destroyed the temples, but believes that the story of him doing so may derive from an anti-Persian sentiment among the Babylonians.[29] It is doubtful if the statue was removed from Babylon at all[25] and some have even suggested that Xerxes did remove a statue from the city, but that this was the golden statue of a man rather than the statue of the god Marduk.[30][31] Though mentions of it are lacking considerably compared to earlier periods, contemporary documents suggest that the Babylonian New Year's Festival continued in some form during the Achaemenid period.[32] Because the change in rulership from the Babylonians themselves to the Persians and due to the replacement of the city's elite families by Xerxes following its revolt, it is possible that the festival's traditional rituals and events had changed considerably.[33]

Invasion of Greece

[edit]

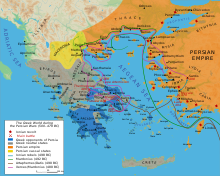

Mardonius, a son of Gobryas and son-in-law of Darius, who had led the Persian expedition in Thrace, but was dismissed due to lack of progress, had been restored to his position after his successor Datis suffered a loss at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC.[34] Mardonius encouraged Xerxes to intiate another Persian expedition into Greece.[34]

Death

[edit]

Xerxes was killed alongside his son and designated successor Darius in a coup in August 465 BC.[35] The details regarding the incident is unclear; the perperators behind the assassination was seemingly Xerxes' son Artaxerxes, who conspired with some influental eunuchs of the empire.[35] Artaxerxes ascended the throne as Artaxerxes I.

Government

[edit]Building projects

[edit]Religion

[edit]While there is no general consensus in scholarship whether Xerxes and his predecessors had been influenced by Zoroastrianism,[36] it is well established that Xerxes was a firm believer in Ahura Mazda, whom he saw as the supreme deity.[36] However, Ahura Mazda was also worshipped by adherents of the (Indo-)Iranian religious tradition.[36][37] On his treatment of other religions, Xerxes followed the same policy as his predecessors; he appealed to local religious scholars, made sacrifices to local deities, and destroyed temples in cities and countries that caused disorder.[38]

Legacy

[edit]Ancestry

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ According to plate 2 in Stoneman 2015; though it may also be Darius I.

- ^ Jürgen von Beckerath (1999), Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen, Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-2310-7, pp. 220–221

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. 9.

- ^ a b Marciak 2017, p. 80; Schmitt 2000

- ^ Schmitt 2000.

- ^ a b Stoneman 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Radner 2013, p. 454.

- ^ Briant 2002, pp. 158, 516.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, pp. viii–ix.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. ix.

- ^ Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 70.

- ^ Waters 1996, pp. 11, 18.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 132.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 520.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Stoneman 2015, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Stoneman 2015, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Stoneman 2015, p. 29.

- ^ a b Dandamayev 1989, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Shahbazi 1994, pp. 41–50.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Briant 2002, p. 525.

- ^ Dandamayev 1983, p. 414.

- ^ a b c d e Dandamayev 1993, p. 41.

- ^ Stoneman 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Dandamayev 1989, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Sancisi-Weerdenburg 2002, p. 579.

- ^ Deloucas 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Waerzeggers & Seire 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 544.

- ^ Deloucas 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Deloucas 2016, p. 41.

- ^ a b Dandamayev 1989, p. 188.

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Malandra 2005.

- ^ Boyce 1984, pp. 684–687.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 549.

Sources

[edit]- Bachenheimer, Avi (2018). Old Persian: Dictionary, Glossary and Concordance. Wiley and Sons. pp. 1–799.

- Boyce, Mary (1979). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. pp. 1–252. ISBN 9780415239028.

- Boyce, Mary (1984). "Ahura Mazdā". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. pp. 684–687.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. pp. 1–1196. ISBN 9781575061207.

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. London et al.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (2000). "Achaemenid taxation". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004091726.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1993). "Xerxes and the Esagila Temple in Babylon". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 7: 41–45. JSTOR 24048423.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1990). "Cambyses II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 726–729.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1983). "Achaemenes". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 4. p. 414.

- Deloucas, Andrew Alberto Nicolas (2016). "Balancing Power and Space: a Spatial Analysis of the Akītu Festival in Babylon after 626 BCE" (PDF). Research Master's Thesis for Classical and Ancient Civilizations (Assyriology). Universiteit Leiden.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2017). "The Achaemenid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 9780692864401.

- Malandra, William W. (2005). "Zoroastrianism i. Historical review up to the Arab conquest". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Marciak, Michał (2017). Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene: Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West. BRILL. ISBN 9789004350724.

- Radner, Karen (2013). "Assyria and the Medes". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Sancisi-Weerdenburg, Heleen (2002). "The Personality of Xerxes, King of Kings". Brill's Companion to Herodotus. BRILL. pp. 579–590. doi:10.1163/9789004217584_026. ISBN 9789004217584.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Schmitt, Rüdiger (2000). "Xerxes i. The Name". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, Shapur (1994), "Darius I the Great", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 7, New York: Columbia University, pp. 41–50

- Stoneman, Richard (2015). Xerxes: A Persian Life. Yale University Press. pp. 1–288. ISBN 9781575061207.

- Waerzeggers, Caroline; Seire, Maarja (2018). Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence (PDF). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-3670-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Waters, Matt (1996). "Darius and the Achaemenid Line". London: 11–18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)