User:HistoryofIran/Tat people (Caucasus)

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:HistoryofIran/Tat_people_(Caucasus). |

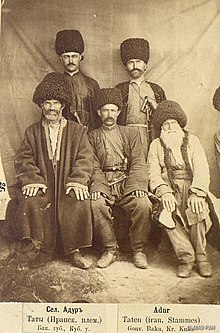

1880 photograph depicting a group of Tat men from the village of Adur in the Russian Empire | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Tat | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranian peoples, Armeno-Tats |

History

[edit]The Tat language (also known as Caucasian Persian and Caucasian Tat) is a southwestern Iranian language descended from Middle Persian.[1][2] Tati speakers are said to be descended from military settlers from southwestern Iran who moved to southern Dagestan during the era of the pre-Islamic Sasanian Empire (224–651).[3] The language is spoken by three groups, the Muslim Tats, the Mountain Jews and Christian Armeno-Tats.[3] Similar to the name "Tajik", the word "Tat" was originally used in early Turkic with the general sense of "alien, non-Turk," but it quickly came to be applied to Persians with a slightly disdainful flavor.[4] The Tats have different self-designations, such as "Pars", "Lohij", "Daghli", and "Tat".[1]

Tati was amongst the Iranian languages that survived the Turkification of the eastern part of the South Caucasus which began in the 11th–14th centuries, remaining the primary language of the Absheron peninsula and the Baku region until the mid-19th century.[5] Russia more or less openly pursued a policy to free their newly conquered land from Iran's influence. By doing this, the Russian government helped to create and spread a new Turkic identity that, in contrast to the previous one, was founded on secular principles, particularly the shared language. As a result, many Iranian-speaking residents of the future Azerbaijan Republic at the time either started hiding their Iranian ancestry or underwent progressive assimilation. The Tats and Kurds underwent these integration processes particularly quickly.[6]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Tonoyan 2019, p. 367 (note 2).

- ^ Lornejad & Doostzadeh 2012, p. 144.

- ^ a b Thordarson 1990, pp. 92–95.

- ^ Bosworth & Jeremiás 2000.

- ^ Tonoyan 2019, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Ter-Abrahamian 2005, p. 121.

Sources

[edit]- Bosworth, C.E. & Jeremiás, Éva (2000). "Tat". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Ebrahimi, Masoumeh (2018). "تات". The Great Islamic Encyclopaedia (in Persian).

- Lornejad, Siavash; Doostzadeh, Ali (2012). Arakelova, Victoria; Asatrian, Garnik (eds.). On the modern politicization of the Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi (PDF). Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies.

- Ter-Abrahamian, Hrant (2005). "On the Formation of the National Identity of the Talishis in Azerbaijan Republic". Iran and the Caucasus. 9 (1). Brill: 121–144. doi:10.1163/1573384054068132.

- Thordarson, Fridrik (1990). "Caucasus ii. Language contact". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume V/1: Carpets XV–C̆ehel Sotūn, Isfahan. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 92–95. ISBN 978-0-939214-66-2.

- Tonoyan, Artyom (2019). "On the Caucasian Persian (Tat) Lexical Substratum in the Baku Dialect of Azerbaijani. Preliminary Notes". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 169 (2): 367–378. doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.169.2.0367. S2CID 211660063.