User:HIST336Cities/sandbox

French Regime

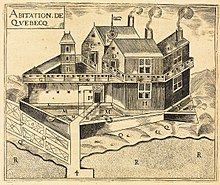

[edit]Quebec City was founded by the French explorer and navigator Samuel de Champlain in 1608. Prior to the arrival of the French, the location that would become Quebec was the home of a small Iroquois village called "Stadacona".[1] Jacques Cartier, a French explorer, was the first European to travel in the St. Lawrence Gulf and who first claimed the land that later became “New France” was the first Frenchman to spend a harsh winter with his crew near Stadacona when he did so during his second voyage in 1535.[2] The word "Kebec" is an Algonquin word meaning "where the river narrow"[3]; a term which describes the geographical characteristics of the St. Lawrence River in the area around Quebec City. When Champlain came to Stadacona, the Iroquois population disappeared and was replaced by Algonquins. Champlain and his crew built a wooden fort which they called "l"Habitation" within only a few days of their arrival in Stadacona.[4] This early fort became the first trading post in New France which exists today as a historical site in Old Quebec. Quebec City’s maritime position and the presence of cliffs overlooking the St. Lawrence River made Quebec an important location for military battles and economic exchanges between the Amerindians and the French[5] In 1620, Champlain build the Fort Saint-Louis on the top of Cape Diamond, near the present place of Chateau Frontenac near the Citadel of Quebec City and the Esplanade in the Upper Town.[6] Quebec City’s 400th anniversary was celebrated in 2008 and it is the oldest city in North America that has a French speaking community.[7]

Demographics and Population

[edit]

The first true colonization efforts by the French occurred in 1608. Samuel de Champlain built “L’Habitation” to house 28 people. [8] However, the first winter proved formidable, and 20 of 28 men died.[9] By 1615, the first four missionaries arrived in Quebec, proving an early introduction of the church. Among the first successful French settlers were Marie Rollet and her husband, Louis Hebert, credited as “les premier agriculteurs du Canada”[10] by 1617. The first white child born in Quebec was Helene Desportes, in 1620, to Pierre Desportes and Francoise Langlois, whose father was a member of the Hundred Associates.[11] The population of Quebec City arrived at 100 in 1627, less than a dozen of whom were women.[12] However, with the invasion of Quebec by David Kirke and his brothers in 1628, the population would see a sharp decline, when Champlain returned to France with approximately 60 out of 80 settlers.[13]

When the French returned to Quebec in 1632, they constructed a city based on the framework of a traditional French “ville”[14] in which “the 17th century city was a reflection of its society."[15] Quebec remained an outpost until well into the 1650’s.[16] The vast majority of emigrants were lower-middle class French peasants. As in other locations throughout New France, the population could be split into the colonial elites, including clergy and government officials, the craftsmen and artisans, and the engages and other indentured servants and slaves.[17] Quebec was designed so that the inhabitants of better quality lived in the upper city, closer to the centers of power such as the government and Jesuit’s college, whereas the lower town was primarily composed of those relating to shipping, trade, and artisans.[18] The city only contained about thirty homes in 1650, and one hundred by 1663, for a population of over 500.[19] Jean Bourdon, the first engineer and surveyor of New France, helped plan the city, almost from his arrival in 1634.[20] However, despite attempts to utilize urban planning, the city quickly outgrew its planned area. Population numbers continually increased, with the city boasting 1,300 inhabitants by 1681. [21] The city quickly experienced overcrowding, especially in the lower town, which contained 2/3 of the population of the city by 1700.[22] The numbers became more evenly distributed by 1744, with the lower town housing only a third of the population, and the upper town containing almost half the inhabitants.[23]

By the 17th century, Quebec also saw a rise in the number of rental dwellings, to help accommodate a mobile population of seamen, sailors, and merchants, aptly described by historian Yvon Desloges as “a town of tenants.”[24] Thus, Quebec followed a pattern common throughout New France, of immigrants arriving for several years, before returning home to France. As a whole, approximately 27,000 immigrants came to New France during the French regime, only 31.6% of whom remained.[25] Despite this, by the time of British occupation in 1759, New France had evolved to a colony of over 60,000 with Quebec as the principal city.[26]

Military and Warfare

[edit]In 1620, the construction of a wooden fort called Fort Saint-Louis started under the orders of Samuel de Champlain. It was completed in 1626.[27] In 1629, the Kirk brothers under English order took control of Quebec City until the French drove them out in 1632 during the Anglo-French War (1627-1629).[28] In 1662, to save the colony from frequent Iroquois attacks during the Beaver Wars, Louis XIV dispatched one hundred regulars to the colony. Three years later, in 1665, Lieuitenant-General de Tracy arrived at Quebec City with four companies of regular troops. There were approximately 1,300 regular troops in the colony by this time.[29] In 1690, Admiral Phips’ fleet failed to capture Quebec City during King William's War. Under heavy French artillery fire, the English fleet was considerably damaged and an open battle never took place. After having used most of their ammunitions, the English retreated out of discouragement.[30] In 1691, Louis de Buade de Frontenac constructed the Royal Battery.

In 1711, during Queen Anne's War, Admiral Walker’s fleet failed to siege Quebec City due to a navigational accident. Walker’s initial report stated that 884 soldiers perished. This number was later revised to 740.[31]

During the Seven years War, in 1759, the British besieged Quebec City for three month under the command of General Wolf. Under the orders of the Marquis de Montcalm, the French tried to break the siege unsuccessfully. The very short battle of the Plains of Abraham lasted approximately 15 minutes and led to a British victory.[32]

The State

[edit]Quebec City served as the hub of religious and government authority throughout the duration of French rule over the city. From 1608 until 1663, Quebec City was the main administrative center of the Company of New France (see Company of One Hundred Associates). During this period, Quebec City was the home of the company’s official representative, the Governor, along with his lieutenant and a number of other administrative officials and small number of soldiers.[33] Following the Royal Takeover of 1663 by King Louis XIV and Jean Baptiste Colbert, Quebec City became the official capital of New France and the seat of a reformed colonial government which included the new post of a Governor General of New France responsible for military and diplomatic matters and an Intendent resposible for more administrative functions involving law and finance.[34] Both the Governor and Intendent were directly answerable to the Minister of the Navy (Ministres Francais de la Marine et des Colonies) and appointed by the King of France.[35] The first Governor to arrive in Quebec City directly appointed by the King was Augustin de Saffray de Mésy in 1663.[36] Moreover, Quebec City became the seat of newly established Sovereign Council which served legislative and legal functions in the colony through its role in the ratification of royal edicts and as final court of appeal[37]. The Council contained the twin heads of the colonial government: The Governor and The Intendent (also the chair), along with the Bishop of Quebec who owed his position in government to the fusion between Church and State in Colonial New France. Moreover, the council contained a number of colonial elites, usually merchants from Quebec City.[38] Noteworthy is the fact that Quebec under the French regime did not contain a municipal government as the French regime intended to avoid any potential centers of opposition which had been characteristic of the political situation resulting in the decentralized contemporary France.[39]

Furthermore, Quebec City was also the focal point of religious authority in New France and had been since the arrival of the first Recollets missionaries in the city in 1615.[40] Working closely with the State, the Church ensured that the colony remained a well regulated Catholic colony.[41] Quebec City became seat of the bishop in the colony upon the creation of the diocese of Quebec in 1674.[42] Moreover, Quebec City was home to the Seminaire de Quebec, founded in 1663 by Laval, who was at the time Vicar apostolic. Laval's experience in the role of Vicar Apostolic highlights the intricate nature of relationship between Church and State in Quebec; while allied with the authority of Rome and the Jesuits on account of his position of Vicar Apostolic, Laval also required the approval from a royal government suspicious of Papal power.[43] Although the State and Church based in Quebec City worked closely together, the dominance of the Crown was retained through the responsibility of the Crown in nominating of the bishop and the supply of a large portion of Church funds[44]

Economics

[edit]As Quebec was settled for its location on the St. Lawrence River with a deep-water harbor, shipping and import/exports dominated the economy. From Cartier’s first arrival, he noticed thousands of Basque fishermen exploiting the cod resources of the region.[45] As a port city, Quebec ran a flourishing trade with the French West Indies and merchants in France. However, trade was restricted to French vessels only trading in officially French ports.[46] As one might expect, smuggling occurred frequently.[47] Inhabitants of Quebec were known to trade furs to the English settlement at Albany through the Iroquois, often turning a blind eye.[48] The economy of New France as a whole consisted, by 1722, of 12% fur, 74% agriculture (including subsistence), and 14% as other goods, thus demonstrating that trade did not dominate the colonial marketplace on the whole.[49] However, what trade did occur in New France, primarily occurred in Quebec. In trade with France, Quebec received wine, textiles and cloth, metal products such as guns and knives, salt, and other small consumer and luxury goods not manufactured in the colony.[50] From the French West Indies, Quebec received sugar, molasses, and coffee. In order to offset their debts, Quebec City facilitated the export of furs to France, as well as lumber for shipbuilding. From 1612 to 1638, 15-20,000 beaver pelts were shipped to France, valued at 75,000 livres.[51] The peace experienced in the early 1720's caused a spike in shipping, with 20 to 80 ships arriving annually at the port of Quebec, with an average of 40 a year. [52]However, Quebec was constantly faced with a trade imbalance, debt, and a certain amount of financial insecurity. As with other colonial societies, there was little hard money throughout the colony.[53] To merchants in Quebec, such a situation proved a particular challenge, as they lacked hard specie, or currency, with which to trade.[54] At one point, the city began the use of playing cards as money in order to reimburse soldiers and other government employees for services rendered when shipments of hard currency failed to arrive. [55] Contentions that the residents of Quebec were poor merchants have, in recent years, been refuted, as historians describe a sharp business acumen, severely circumscribed by a lack of finances.

Religion

[edit]The Catholic faith played a significant role in the settling and development of Quebec City. With the first missionaries arriving in 1615, Quebec was, from its founding, a Catholic city. Although those of other faiths were permitted to practice their faith in private, the city embraced Catholicism as an integral part of daily life.[56] The Recolettes were the first religious order to arrive in 1615, followed by the Jesuits in 1625, who would found a college in Quebec City by 1635.[57] Female religious orders arrived by 1639, with the Ursulines providing education, and the Augustinians servicing the Hôtel Dieu de Québec. The conceding of seigneuries to religious orders helped solidify their place as a facet of society.[58] Indeed, much of the upper town of Quebec came to be held by religious orders. [59] The arrival of Francois de Laval as the vicar apostolic to Quebec in 1658 cemented the place of religion in Quebec City.[60] The city would become a formal parish in 1664, and a diocese by 1674.[61] The Catholic faith not only played a large role in the government and legislation, but also in the social lives of residents. As Quebec City was the seat of religion throughout New France, inhabitants followed the strict schedule of fasting, holy days, and celebrating sacraments, in addition to the censorship of books, dancing, and theatre.[62] After the English invasion of Quebec, the residents were permitted to continue practicing Catholicism under the Act of Quebec in 1774. [63]

References

[edit]- ^ Bumsted, J. M. Canada's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. 35.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Conrick, Maeve, and Vera Regan. French in Canada: Language Issues. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2007. 11-12.

- ^ Vallières, Marc. "Québec City." The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/quebec-city.

- ^ "Quebec, a New French Colony (1608-1755)." Ville De Quebec. http://www.ville.quebec.qc.ca/EN/apropos/portrait/histoire/1608-1755.aspx.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Canada. Statistics Canada. City of Quebec 1608-2008: 400 Years of Censuses. By Gwenaël Cartier.

- ^ Jean Provencher, Chronologie du Quebec, 1534-2007, Montreal: Boreal, 2008. 35.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Provencher, 35.

- ^ Dictionary of Canadian Biography, “Helene Desportes,” Accessed online at http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=172

- ^ Provencher, 31.

- ^ Provencher, 32.

- ^ Remi Chenier, Quebec, A French Colonial Town in America, 1660-1690, Ottawa: Minister of the Environment, 1991.

- ^ Chenier, 18.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Marc Vallieres, Quebec City, A Brief History, Quebec: Les Presses de l’Universite Laval, 2011, 49.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Vallieres, 29.

- ^ Serge Courville and Robert Gagnon, Québec, ville et capital, Sainte-Foy: Université de Laval, 2001. 52.

- ^ Vallieres, 48.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Vallieres, 51-51.

- ^ Peter Mook, "Reluctant Exiles: Emigrants from France in Canada before 1760", William and Mary Quarterly Vol 46. No. 3, 1989. 463.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Quebec City Heritage, access online at http://www.quebecheritage.com/en/militaire.html

- ^ Idem

- ^ W.J Eccles: Essays on New France, page 111

- ^ History of the USA, access online at http://www.usahistory.info/colonial-wars/King-Williams-War.html

- ^ Chronicles of America, access online at http://www.chroniclesofamerica.com/new-france/queen_annes_war.htm

- ^ The Canadian Encyclopedia, access online at http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/seven-years-war

- ^ Dube, Jean Claude, and Elizabeth Rapley. The Chevalier De Montmagny (1601-1657): First Governor of New France. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2005. 127.

- ^ Greer, Allan. "The Urban Landscape." In The People of New France, 44-45. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

- ^ Quebec, a New French Colony (1608-1755)." Ville De Quebec. http://www.ville.quebec.qc.ca/EN/apropos/portrait/histoire/1608-1755.aspx.

- ^ Eccles, W. J. "Saffray De Mézy." Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, 2000. http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=25 [

- ^ http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/new-france

- ^ Greer, Allan. The People of New France. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

- ^ Lecture, Professor Alan Greer, February 13, 2012, McGill University, Montreal, QC

- ^ http://www.ville.quebec.qc.ca/EN/apropos/portrait/histoire/1608-1755.aspx

- ^ Greer, 45.

- ^ http://www.ville.quebec.qc.ca/EN/apropos/portrait/histoire/1608-1755.aspx

- ^ Monteyne, J. "Absolute Faith, or France Bringing Representation to the Subjects of New France." Oxford Art Journal 20, no. 1 (1997): 12-22. JSTOR.

- ^ Eccles, W. J. Essays on New France. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1987. 33.

- ^ Mark Kurlansky, Cod, A Biography of a Fish that Changed the World, New York: Walker and Co.1997. 29.

- ^ Lecture, Professor Alan Greer, February 8, 2012, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Vallieres, 24.

- ^ Vallieres, 32.

- ^ Lecture, Professor Alan Greer, February 8, 2012, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ « Reglements généraux du conseil souverain pour la police…, 11 mai 1676, » Pierre Georges Roy, ed., Inventaire des jugements et délibérations du conseil supérieur de la Nouvelle-France de 1717 à 1760, 7 vols. (Beauceville: L'"Eclaireur," 1932), 1: 190-205.

- ^ Vallieres, 25.

- ^ Vallieres, 26.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Vallieres, 25.

- ^ Vallieres, 45.

- ^ Vallieres, 45.

- ^ Provencher, 121