User:Grayrado/sandbox

Asturleonese Language

[edit]The Asturleonese language (also referred to as Asturian or Leonese) is a Romance language, spoken primarily in northwestern Spain, known for its many dialects including, Asturian, Leonese, and Miranda.[1] This language has been classified by UNESCO as an endangered language, as Asturian is being increasingly replaced by Spanish.[2]

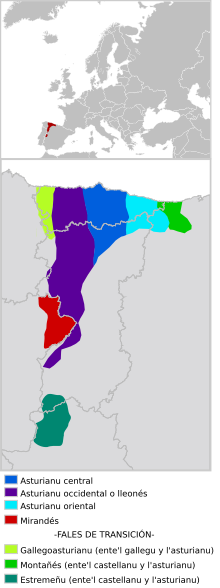

Asturleonese is a part of the group of Western Iberian Romance languages and evolved from vulgar Latin under the Austrian reign. The linguistic region of the Asturleonese language stretches from Asturias in the north until the northern part of Portugal at its southernmost point. The language consists of three main linguistic subgroups: occidental, central and oriental.[3] The "montañés" in the east and the "extremeño" in the south are linguistic variations of Asturleonese, all with similar qualities to the oficial language of Spanish. While there exist differing degrees of vitality between regions in the area, Asturias and Miranda del Douro have historically been the regions in which Asturleonese has been the best preserved.[4][5]

Brief History

[edit]The Asturleonese language originated from Latin, which was mainly transmitted through the Roman legions in Asturica Augusta as well as the Legionnaire VI. The adoption of Latin by the Astures, who inhabited the area, was a slow process but an inevitable one, as the use of the colonial language was the key to obtaining equal rights; the most important priority, at the time, being to earn Roman citizenship. However, like the rest of the peninsula, it was not until the establishment of the German reign that Latin came to be the common spoken language of the area.[6]

Along with many linguistic similarities to Latin, the Asturian language also has distinct Roman characteristics that can be linked back to the Cantabrian Wars; a conflict in which the northern villages of Leon and Asturias fought against the incorporation of the Roman culture. These two linguistic influences, together with the expansion and the subsequent regression of vernacular languages, such as Basque, would determine the linguistic evolution in the northwestern part of the peninsula. The vocabulary of Asturleonese contains pre-romanic elements that survived the later romanization of the area, as well as including pre-Indoeuropean elements that were only maintained through typonymy.[7]

Diglossia and the Language of Castellano

[edit]For a long time, during the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries, Latin and Asturian co-existed within a diglossic relationship. During this time, Asturleonese was used in official documents and shared a high legal status than the it would within the following centuries.[8] However, the period of time between the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, many linguistic dialects were marginalized within the Iberian Peninsula as well as other parts of Europe. Because of this, many linguistic dialects were omitted and many cultural minorities were marginalized, making it dangerous for some languages, such Asturleonese, to exist and resulted in the fragmentation of others.[9]

During the nineteenth century, the Asturian territories were included as part of the Spanish circle. During this time, Spanish thrived as a language of prestige and culture which led to its replacing Asturleonese in these areas, as well as in the neighboring Galicia, leaving it to mainly oral usage. Consequently, there existed, and still exists, a distinct divide between the spoken languages of Spanish and Asturian and the written ones.[10]

This being said, diglossia exists today within the region of Asturias. While Spanish is the official language, being used in the government and political spheres, the Asturian language survives as the language mainly used in informal and casual conversation within these communities.[4] Additionally, the language is often offered as an elective in schools throughout the linguistic region.[11]

Legal Status

[edit]Asturleonese only recently received recognition in the municipality of Miranda de Duero by virtue of Portuguese law 7/99 on January 29, 1999, although merely as a language that should continue to be protected and preserved, not awarding it any official status within Asturias. Meanwhile, Catalan, Basque, and Galician were all granted official status in their respective regions in 1978.[12] Therefore, there exists some tension, as Asturleonese is still not regarded as an official language today.[13][14]

The Spanish Constitution recognizes the existence of vehicular languages and the need for the protection of existing dialects within the national territories. In article 3.3 of the constitution, the document concretely states that "the richness of the distinct linguistic modalities of Spain is a cultural heritage that will be the subject of special respect and protection." Additionally, article 4 states that, "The Asturian language will enjoy protection. Its use, teaching and diffusion in the media will be furthered, whilst its local dialects and voluntary apprenticeship will always be respected."[15] In light of these stated provisions of the 1/1998, on the 23 of March, on the Use and Promotion of the Asturleonese Language serves this purpose; promoting the use of the language, its knowledge within the educational system, as well as its dissemination in media. However, Asturleonese continues to have a very limited presence within the government.

Geographic Distribution

[edit]Linguistically, it's considered that within the dominion of Asturleonese, the known dialects such as Leonese, Asturiano, or Mirandese form part of a macrolanguage. A macrolanguage is a language that exists as distinct linguistic varieties. Within this macrolanguage, dialects such as the Occidental and Oriental share some linguistic characteristics with Galaicoportuguese and Castellano.[16][17][18]

Linguistics have shown how the boundaries of the Asturleonese language extend through Asturias, Leon, Zamora, and Miranda do Douro. The common characteristic of Asturleonese in every area, however, is that the language is not characterized for being an aggregation of an Asturian, Leonese, Zamorano, or Mirandan dialect; the first linguistic divisions of Asturleonese are vertical divisions that form three separate sections that are shared between Asturias and Leon: occidental, central, and oriental. Only through a second level of analysis were smaller sections able to be expressed. The political and administrative entities and linguistic spaces rarely coincided, as it's most common that languages go beyond borders and do not coincide with them.[19][20][21][22]

Number of Speakers

[edit]There is no known, exact number of Asturleonese speakers, as not enough statistical research has been conducted in this area and many dialects are not accounted for due to their close similarities with Spanish. It is believed that there are over 100,000 Asturian speakers within Spain and Portugal.[23] However, a study conducted in 1991 on the specific Asutrian dialect, showed that there could be as many as 450,000 speakers within the Asturias region, with about 60,000 to 80,000 able to read and write the language. The same study indicated that another 24 percent of the population could understand Asturian.[24] This also explains the diverse range of knowledge and familiarity that those within the region have of the Asturleonese language, as there exist some speakers, some who can only understand the language, and a very small portion of the population who are able to read and write.

References

[edit] | This is a user sandbox of Grayrado. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

- ^ Menéndez Pidal, Ramón (2006). El dialecto leonés (Edición conmemorativa con relatos y poemas en leonés). El Búho Viajero. ISBN 978-84-933781-6-5.

- ^ Muñiz-Cachón, Carmen (2019-12-31). "Prosody: A feature of languages or a feature of speakers?: Asturian and Castilian in the center of Asturias". Spanish in Context. 16 (3): 462–474. doi:10.1075/sic.00047.mun. ISSN 1571-0718.

- ^ Alenza García, José Francisco (2010-12-29). "1.16. Legislació ambiental Navarra (Segon semestre 2010)". Revista Catalana de Dret Ambiental. 1 (2). doi:10.17345/1108. ISSN 2014-038X.

- ^ a b de Andrés Díaz & Viejo Fernández. (n.d.) Rapport about the Institutional Obstacles to the Normalization of the Asturias Language. Actas / Proceedings II Simposio Internacional Bilingüismo. http://ssl.webs.uvigo.es/actas2002/04/06.%20Ramon%20de%20Andres.pdf

- ^ Hernanz, Alfonso, "ASTURLEONÉS MEDIEVAL; UNA APROXIMACIÓN SINCRÓNICA Y DIACRÓNICA A SUS RASGOS FONÉTICOS DIFERENCIALES Y SU DOMINIO LINGÜÍSTICO. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2021. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6643

- ^ "Asturian language". www.translationdirectory.com. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ De especial interés son palabras preindoeuropeas que, extendiéndose desde Portugal-Galicia hasta las Provincias Vascongadas, son testimonio aún hoy en día de capas antiquísimas; así, p. ej., el port. samo 'albura', gallego 'id.; la capa blanda que se halla debajo de la corteza de los cuernos', ast. samu 'la superficie', vasc. zama 'albura', o el ast. cotolla'árgoma o tojo, aulaga', gall. cotaño 'cepa de hiniesta', vasco othe 'árgoma', ejemplos tomados de Hubschmid, Enc Hisp I, 1960, pág. 54). En otros casos sólo se han conservado los pilares laterales; así, p. ej., en el caso de la palabra gangorra, 'especie de carapuça', testimoniada por un lado en el port. del siglo XV, y por otro, en el vasco gangorra, 'la cresta'. La relación entre ambas palabras se ve confirmada por la palabra, testimoniada también en las zonas intermedias: montañés, asturiano, Soria ganga, 'puntos extremos del corte de las herramientas (hachas, azuelas, dalles, etc.)' y más allá del vasco en el bearn. gangue 'arête, crête' (d’une montagne)” (J. Hubschmid, Português “gangorra”, RBras 3, 1957, págs. 83-86, y Enc Hisp I, 1960, pág. 56, ver Baldinger Kurt, La formación de los dominios linguísticos,, cit. 1962, 148.

- ^ Campbell, Kenny; Smith, Rod (2013-10-01). "Permanent Well Abandonment". The Way Ahead. 09 (03): 25–27. doi:10.2118/0313-025-twa. ISSN 2224-4522.

- ^ García Arias, Xosé Lluis (2020-10-20). "Dos poemes poco conocíos". Lletres Asturianes (123): 167–174. doi:10.17811/llaa.123.2020.167-174. ISSN 2174-9612.

- ^ Kupka, Tomáš (2013-12-01). "Reflexiones sobre la inexistencia de la base teórica de la creación y evaluación de las hojas de trabajo para la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras con un enfoque en la lengua española". Romanica Olomucensia. 25 (2): 121–125. doi:10.5507/ro.2013.015. ISSN 1803-4136.

- ^ Boyer, Henri (2021-03-01). "Hoja de servicios y futuro de la sociolingüística catalana: una exploración epistemológica (y glotopolítica)". Archivum. 70 (2): 59–81. doi:10.17811/arc.70.2.2020.59-81. ISSN 2341-1120.

- ^ University of Zurich; Bleortu, Cristina; Prelipcean, Alina-Viorela; Stefan cel Mare, University of Suceava (2018-12-21). "The Castilian and Asturian languages in schools". Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala. 10 (4): 241–248. doi:10.18662/rrem/85.

- ^ "Conjunto de datos oceanográficos y de meteorología marina obtenidos en el Crucero Oceanográfico Pacífico XLIV. Colombia. Enero - febrero de 2007". doi:10.26640/dataset_crucero.erfen.2007.01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sánchez, León; Mario (2020-12-28), "ADAGIO EDUCATIVO, LA ÉTICA Y EL DON EN LA EDUCACIÓN.", Una acción educativa pensada. Reflexiones desde la filosofía de la educación, Dykinson, pp. 488–494, retrieved 2021-10-27

- ^ García Benito, Manuel Germán (2018-10-31). "Evolución histórica de la ley de uso y promoción del bable/asturiano en la enseñanza secundaria: orígenes, debates jurídicos, educación y perspectivas de futuro/Historical evolution of the Asturians use and promotion law in the secondary education: origins, legal debates, Education and future prospects". Magister. 29 (2): 29. doi:10.17811/msg.29.2.2017.29-36. ISSN 2340-4728.

{{cite journal}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 198 (help) - ^ de las Asturias, Nicolás Álvarez, "FUNDAMENTOS Y CONSECUENCIAS ECLESIOLÓGICAS DE LA PRIMERA CODIFICACIÓN CANÓNICA", Ley, matrimonio y procesos matrimoniales en los Códigos de la Iglesia, Dykinson, pp. 29–44, retrieved 2021-10-27

- ^ Almeida Cabrejas, Belén (1970-01-01). "Jesús Antonio Cid, "María Goyri. Mujer y Pedagogía - Filología". Madrid, Fundación Ramón Menéndez Pidal, 2016. Elena Gallego (ed.), "Crear escuela: Jimena Menéndez-Pidal". Madrid, Fundación Ramón Menéndez Pidal, 2016". Didáctica. Lengua y Literatura. 29: 285–286. doi:10.5209/dida.57143. ISSN 1988-2548.

- ^ "Métrica y pronunciación en el Libro de Buen Amor: Prototipo del isosilabismo castellano medieval". Analecta Malacitana, Revista de la sección de Filología de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. 2015-12-01. doi:10.24310/analecta.2015.v38i1.4342. ISSN 1697-4239.

- ^ YouTube. «El lingüista Fernando Álvarez-Balbuena explica qué es la lengua asturleonesa (1/4)» (en asturleonés). Consultado el 19 de noviembre de 2009.

- ^ YouTube. «El lingüista Fernando Álvarez-Balbuena explica qué es la lengua asturleonesa (2/4)» (en asturleonés). Consultado el 19 de noviembe de 2009.

- ^ ouTube. «El lingüista Fernando Álvarez-Balbuena explica qué es la lengua asturleonesa (3/4)» (en asturleonés). Consultado el 19 de noviembre de 2009.

- ^ YouTube. «El lingüista Fernando Álvarez-Balbuena explica qué es la lengua asturleonesa (4/4)» (en asturleonés). Consultado el 19 de noviembre de 2009.

- ^ International encyclopedia of linguistics. William Frawley (2nd ed ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-19-530745-3. OCLC 66910002.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ García Arias, Xosé Lluis, "Corrección toponímica en el Principado de Asturias/Principáu d'Asturies", Lengua, espacio y sociedad, Berlin, Boston: DE GRUYTER, retrieved 2021-11-08